3

THE GOSPELS

Although Jesus Christ is the central person of history, very little information about Him can be learned from sources outside of the four Gospels and the rest of the New Testament. Since the first thirty years of His life were lived in obscurity and the latter three or four years of His ministry were localized in Palestine, it would be very unlikely for secular historians and men of literature, residing in Rome, to have written about Him. However, as Christianity spread throughout the Mediterranean world during the first and second centuries, these pagan writers could not ignore the presence of Christians in their midst. Men like Tacitus, Pliny, and Lucian described the new religious sect and traced it back to its founder, Jesus Christ. These early writers, though, made only brief, general allusions to Christ’s teachings, trial, death, and influence upon His followers. A first-century Jewish historian, Josephus, wrote this striking paragraph about Christ, but many textual critics believe it to be spurious, an interpolation inserted by later Christians into his text:

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man, for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews, and many of the Gentiles. He was the Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men among us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians so named from him are not extinct at this day.

It is true that apocryphal gospels were circulated among the early churches, but they were rejected because they did not meet the tests of canonicity. They were not inspired and infallible, free from moral, doctrinal, and historical error. They were not written by authenticated apostles or by their associates. Rather, they contained fanciful legends and mere repetition of canonical truth. They were probably written to enhance and to advance certain heretical viewpoints.

To learn about the life and ministry of the Savior, the believer must look to the Bible, especially to the four Gospels. But why do Christians have any gospel records of the life of Christ? How and why were they composed? These questions and others like them have given rise to the synoptic problem.

The Synoptic Problem

The word "synoptic" comes from two Greek words: sun, meaning "with" or "together," and optanomai, meaning "to see." The word is applied to the first three Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) because they present a common approach to the life of Christ. The Gospel of John is omitted because it contains much distinctive content.

Definition of the Problem

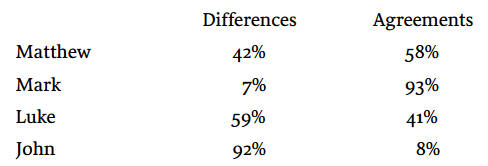

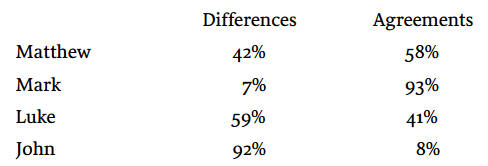

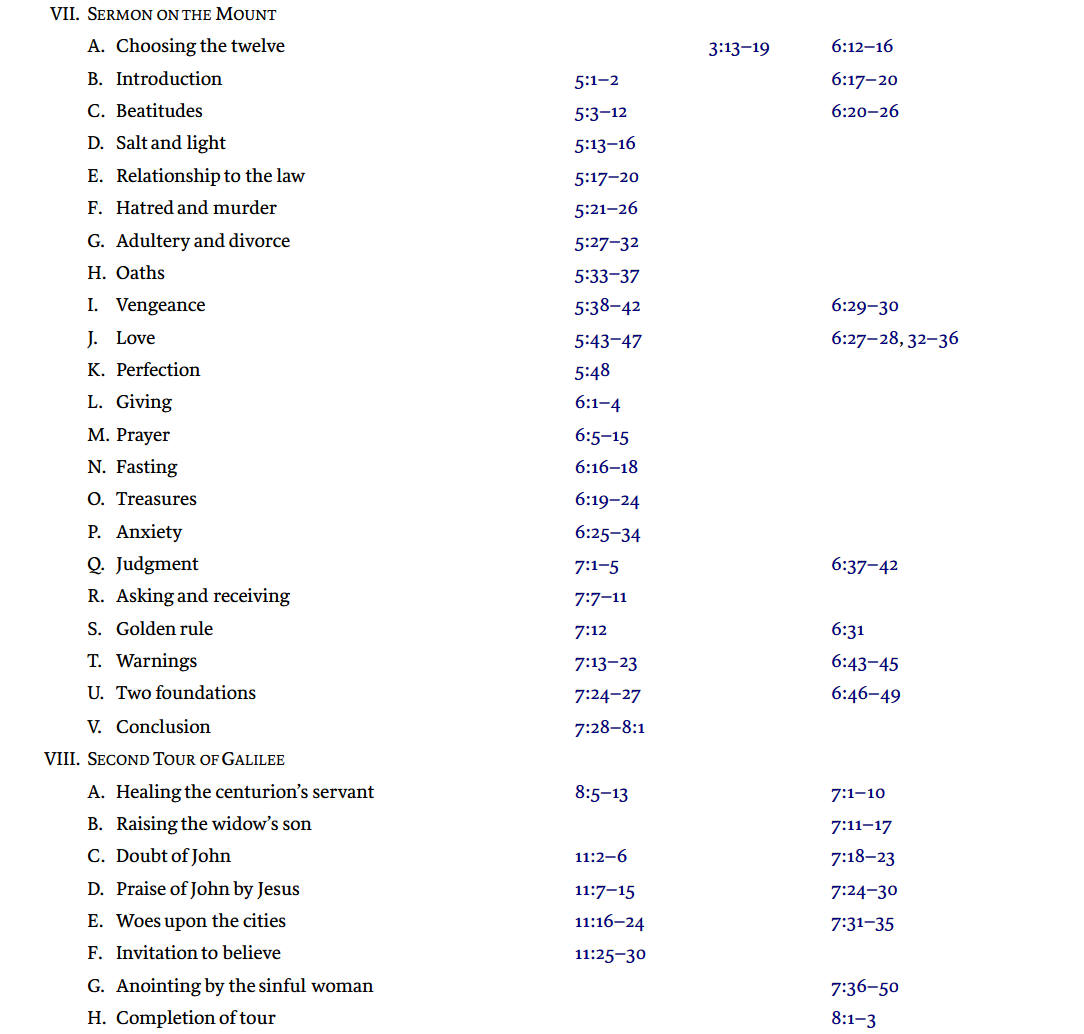

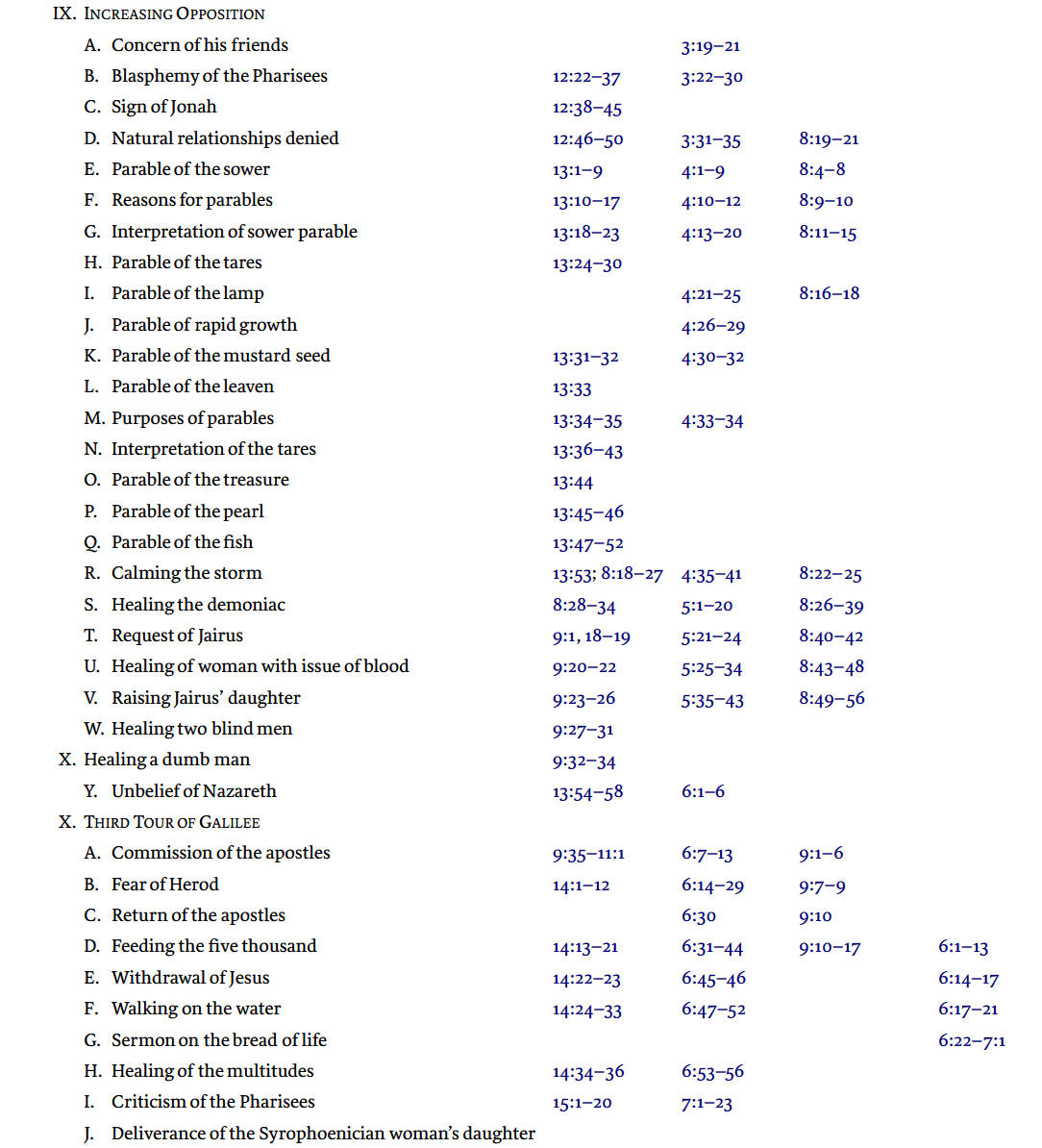

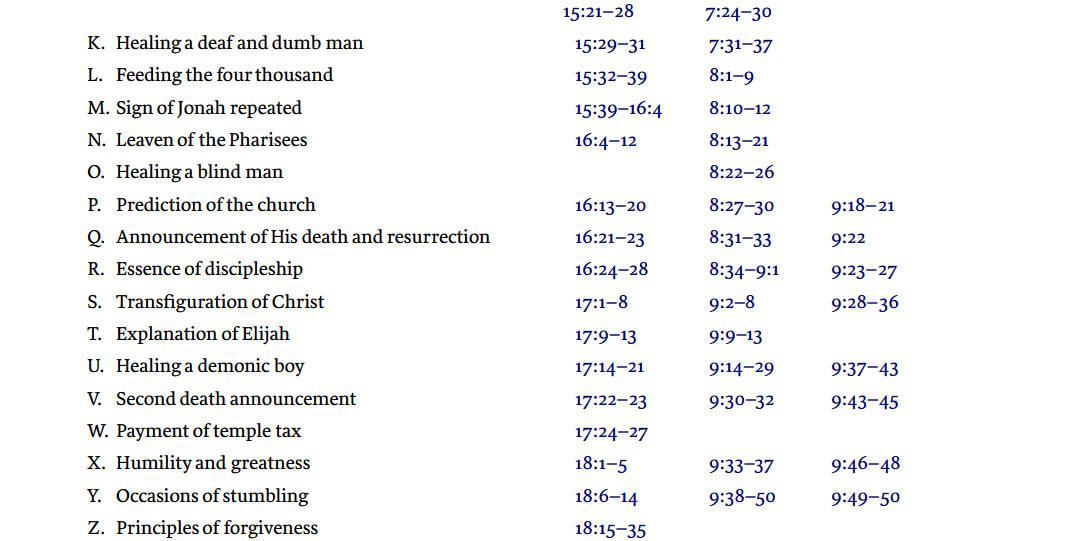

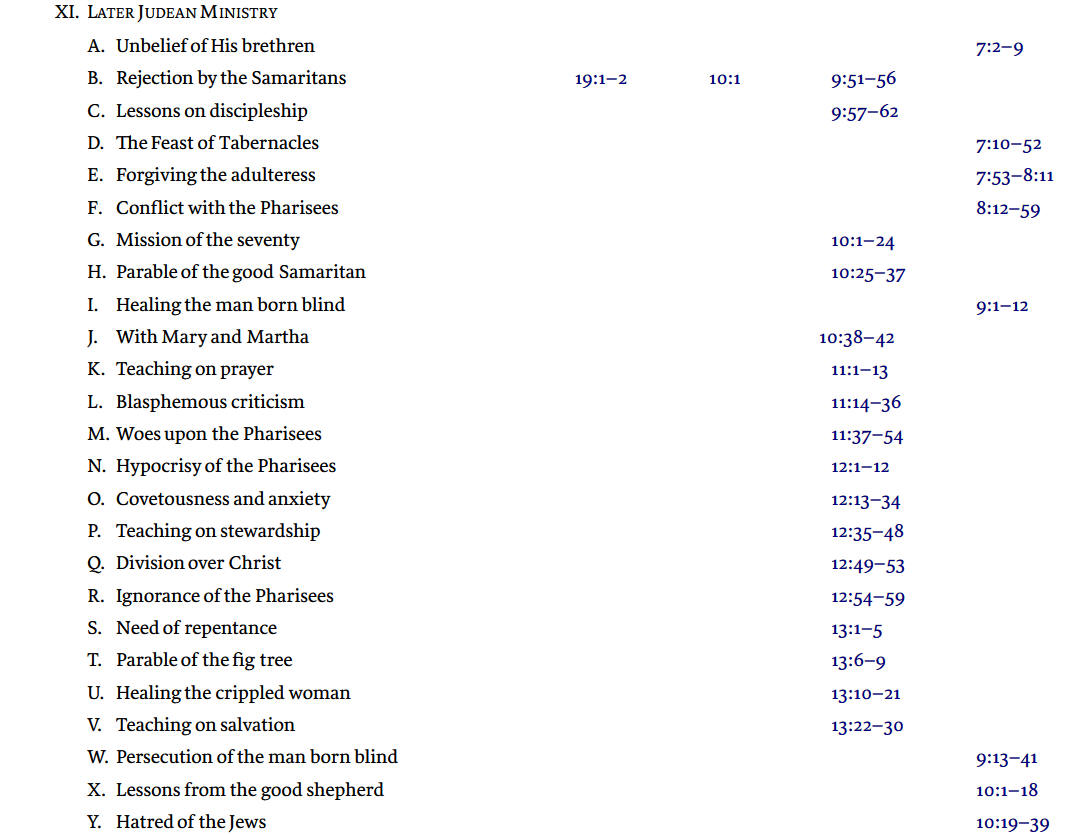

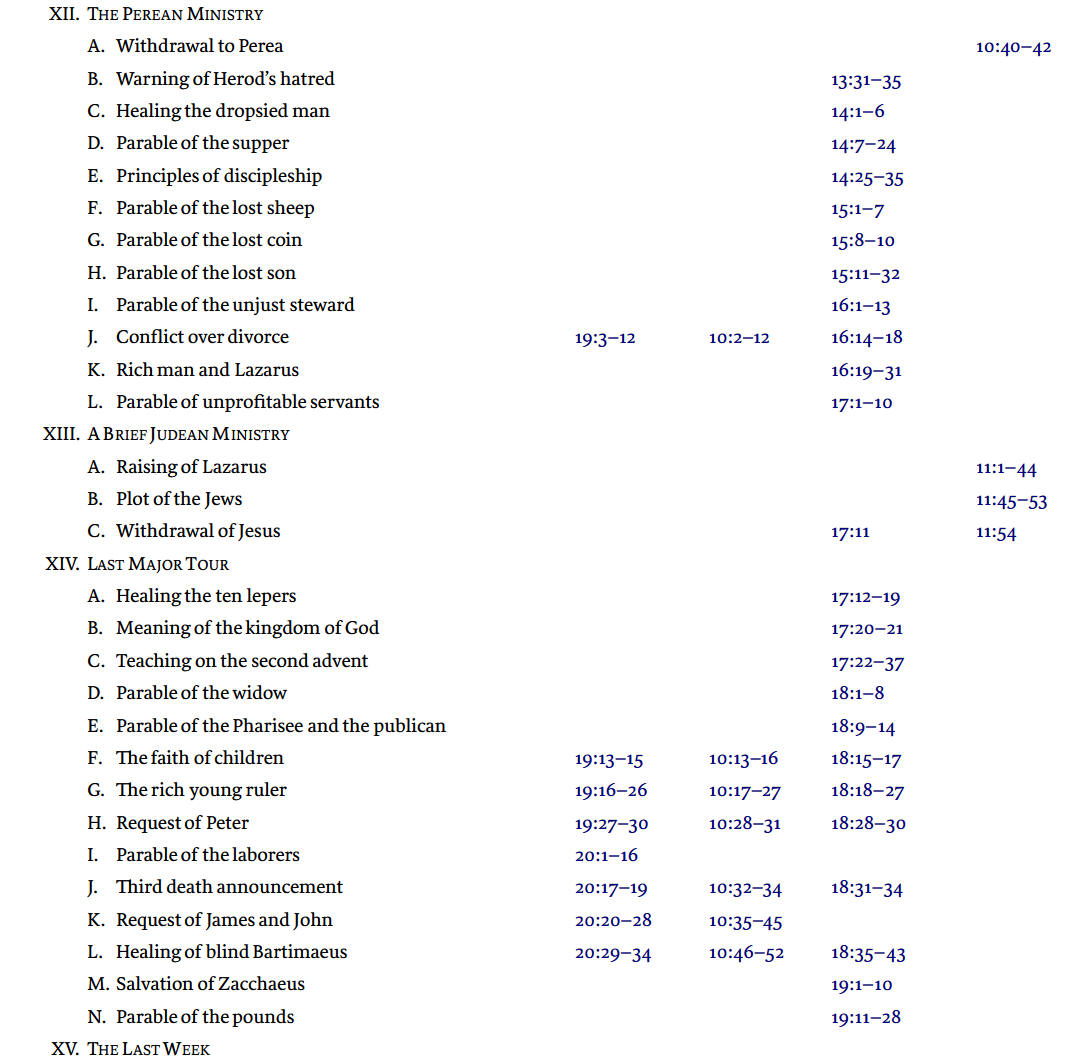

The Synoptic Gospels record a lot of material that is common to all three of them or is found in at least two of them. From his study Westcott determined these percentages of differences and similarities:

Practically the entire Book of Mark can be found within the others. The content of Matthew and Luke is about equally divided between agreements and peculiarities, with Luke having more unique material. The great bulk of John’s narrative is found only within his book. It has been calculated that of the 661 verses in Mark, 610 are parallel to Matthew and Luke. Of the eighty-eight separate paragraphs in Mark, only three are absent from Matthew and Luke.

This bulk of common material has given rise to the synoptic problem with its various questions. How were these pieces of literature constructed? Did the three originate and develop independently of each other? If they did, how can one account for the many similarities among them? Did the writers read each other’s books? Did they incorporate sections of the others into their own volume? Did the writers talk to each other about their respective purposes in writing a life of Christ? Did they have access to a common written source or sources? Did they interview eyewitnesses? Could the Holy Spirit direct two or three men to write the same things, yet independently of each other? Finally, why is there material distinctive to each writer, some content common to all three, and other sections found in only two of them?

Various Proposed Solutions

Most critical work on the synoptic problem has been done from the liberal viewpoint, although some conservatives have also been involved in the study. The solutions offered by liberal scholarship usually reflect a humanistic, naturalistic explanation for the literary composition of the Gospels. Little stress if any is placed upon the guiding work of the Holy Spirit in the lives of the writers. The liberals’ solutions are based upon two major presuppositions. The first is that the writers incorporated unwritten, oral tradition that had been transmitted from the apostles to the churches. The second is that the writers utilized written, documentary sources to structure their content. Naturally, there could be a combination of the two methods. A third alternative is that the writers copied or borrowed from each other’s writings.

The interdependence theory concludes that the first Biblical author used oral tradition as the basis of his Gospel, that the second writer consulted the first Gospel for his content, and that the third author researched both written Gospels to structure his narratives. Although this view has a ring of plausibility, there is no positive evidence that one writer read and used the written Gospel of another. By itself, this concept cannot explain the omissions and differences of content within the Synoptic Gospels.

The oral transmission of tradition theory claims that the direct source of each Gospel was oral tradition received from the preaching ministry of the apostles. As each generation of converts was taught concerning the life of Christ, the tradition became fixed through constant repetition. It is true that the apostles repeated their oral message many times before the first Gospel was penned. Tradition in fact identified Mark and Luke with the preaching ministries of Peter and Paul respectively. However, this view cannot account for the unique material of each writer either. If the oral tradition was so fixed and authoritative, then why did the authors use such liberty in adding and subtracting material? With such a common base, one would expect to find more total agreement on the details involved in the major events of Christ’s life (e.g., trials, death, and resurrection appearances).

Most explanations involve the use of some written sources by the Biblical authors. The fragment theory states that each writer used a large number of short written narratives as the basis of his volume. Although Luke claimed that many gospelettes were in existence before he wrote (Luke 1:1–4), he did not say that he incorporated all or parts of them into his book. Even if he did consult these sources, this does not mean that the other two synoptic writers did likewise. Since the Gospels do manifest a general agreement of event sequence, it would be difficult to see how this could be achieved through an arbitrary employment of random fragments. The urevangelium theory says that there was an original, written gospel or gospelette from which all three synoptic writers drew their materials. This position, however, cannot explain the differences and/or omissions in the common accounts within the three books. The main objection is that there is no objective, manuscript evidence for the existence of this unknown, original gospel. No Biblical or patristic writer ever refers to it. A very popular approach is the two-document hypothesis which states that Matthew and Luke used two main written sources: the Gospel of Mark and another document entitled "Q" by literary critics.4 The Q document became the basis of that material common to Matthew and Luke, but not found in Mark. A four-document theory later developed out of this approach. In this concept, added to Mark and "Q" were an "M" document that was the source of material found only in Matthew and an "L" document containing that content found only in Luke. First of all, it is difficult to prove the priority of Mark. Tradition favors a late date for Mark (a.d. 65). This would mean that Matthew and Luke wrote after a.d. 70 with no reference to the destruction of Jerusalem. If Luke used Mark and wrote his Gospel in the late sixties or seventies, then this creates real problems with the dating of Acts, a book that followed Luke. Luke apparently wrote Acts when Paul was in Rome (c. a.d. 61); the Gospel had to be written in the fifties. Actually, most tradition favors the priority of Matthew. Second, there is no positive, objective manuscript evidence for the existence of such documents designated Q, M, or L. Their existence was never mentioned by the Biblical authors or the Church Fathers. Archaeologists have not unearthed them. Third, it would be difficult to account for the agreements of Matthew and Luke against Mark. If the former two used Mark, why do they agree in some places contrary to Mark? The Gospel of Mark should have served as a check on them. In the final analysis, this approach is based upon a human, evolutionary development of Scripture.

A contemporary critical view is that of the

Formgeschichte school. It attempts to determine the beginnings of the material upon which the various documentary sources are based. It goes beyond the written documents to the oral tradition, the apostolic repetition of the teachings of Jesus. The latter, according to its proponents, can be detected in sermonic stories or epigrams and various historical recitals, such as a recounting of Christ’s death at the observance of the Lord’s Supper. This various biographical data was gathered, collated, structured into a literary framework, and written into a document which became a source for the Gospels.An Evangelical Answer

Do conservatives have an adequate explanation for the synoptic problem? Are they able to account for the striking similarities of the first three Gospels and the unique distinctiveness of John’s Gospel? A concept of strict, verbal dictation by God to human stenographers is incapable of explaining the synoptic phenomena. However, the methods of human expertise that were superintended by the divine Spirit in the production of Holy Writ can be perceived and outlined.

Since two and possibly three of the writers were eyewitnesses of Christ’s activities, they had direct knowledge of those conversations, sermons, and events they recorded. Both Matthew and John were numbered among the twelve apostles. Like Peter, they preached and wrote what they personally observed (John 19:35; cf. Acts 10:37–43; 1 Peter 5:1; 2 Peter 1:14–18). Since Mark was a resident of Jerusalem, he may have heard the teaching of Jesus when He was in the temple and/or the environs of that city. Luke, of course, would not have had any firsthand acquaintance with Christ.

Since the Gospels were written between twenty-five and sixty years after the events had actually occurred, some have argued that even eyewitnesses would not have been able to remember the events accurately. Men, especially aging men, are prone to memory failure. If the Bible were nothing more than a mere human composition, then this argument would carry some weight. However, such critics disregard the promise of Christ to His apostles, including Matthew and John: "But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you" (John 14:26). The ministry of the Holy Spirit enabled the apostles to remember, to preach, and to write accurately the oral ministry of Christ. The science of cybernetics claims that the human brain is like a computer, storing up all data impressed upon it. The Spirit so programmed their memory banks that they were able to remember graphically His words at the critical moment of writing.

Other material could have been gleaned through personal contacts and conversations with those who were eyewitnesses. Matthew doubtless heard from other apostles what the latter witnessed in Matthew’s absence. For example, only Peter, James, and John observed the transfiguration of Christ (Matt. 17:1–2); however, they reported it to the others after the resurrection of Christ (Matt. 17:9). Mark could have easily talked to the apostles since they established their headquarters in Jerusalem for the propagation of the gospel. Luke journeyed with Paul to Jerusalem (Acts 21:17); therefore, he would have had opportunity to talk with a few of the apostles. During the two years of Paul’s Caesarean imprisonment, he would have had ample time to interview many residents of Palestine who had witnessed Christ’s ministry. There is a strong possibility that he could have even consulted with Mary, the mother of Jesus.8 Eyewitnesses were available (Luke 1:2), so all four writers could have talked with such people.

Naturally, some material could have been gained through the hearing of apostolic sermons. Mark doubtless heard many if not all of the apostles’ preaching. Luke heard Paul many times. Although Paul was not a firsthand observer, he had infrequent contacts with the original apostles. However, in his case, the message was given to him directly by Jesus Christ through postresurrection appearances (1 Cor. 15:1–8; Gal. 1:11–12). Mark and Luke were together with Paul in Rome (Philem. v. 24); therefore, Mark could have told Luke about the life of Christ as given in the content of apostolic sermons which he heard.

As previously mentioned, Luke admitted that there were gospelettes or short narratives of Christ’s life in circulation at the time he decided to write (Luke 1:1–4). It is difficult to say how many were known to him and what their contents were. Archaeologists have not discovered any of them. They probably were accounts of isolated events (e.g., a diary account of the cleansing of a leper; Luke 5:12–14) written by men not directed by the Spirit.

It is not even inconceivable that the Holy Spirit could have revealed truth to these writers totally unknown to them. If such a revelation were given to Paul, then the procedure could also be partially true of them. However, in the final analysis, it must be admitted that in all cases the writer consulted sources, both oral and written, scrutinized them, selected material, and wrote under the direct influence of the Holy Spirit. These were not mere human compositions; they were the Word of God inscripturated through human penmen.

The Content of the Gospels

The Gospels do not contain needless repetition. Their content cannot be summed up in the following popular statement: "If you have read one, you’ve read them all." Each Gospel is a distinctive unit by itself. Each was written at a different time for a different readership for a different purpose. A reading of one Gospel will not reveal the total life of Christ. No Gospel writer determined to write an exhaustive, chronological biography. Rather, each selected from a vast reservoir of material those events that would best relate to his purpose (cf. John 20:30–31). These events were then arranged for effect rather than for chronological sequence. The authors were actually writing interpretative commentaries upon Christ’s life rather than a daily chronicle. This is why Mark and John omitted references to Christ’s birth and developmental years; these events did not suit their purpose. This is why John included only eight of Christ’s miracles; the others, although known to him, were not relevant to his literary needs.

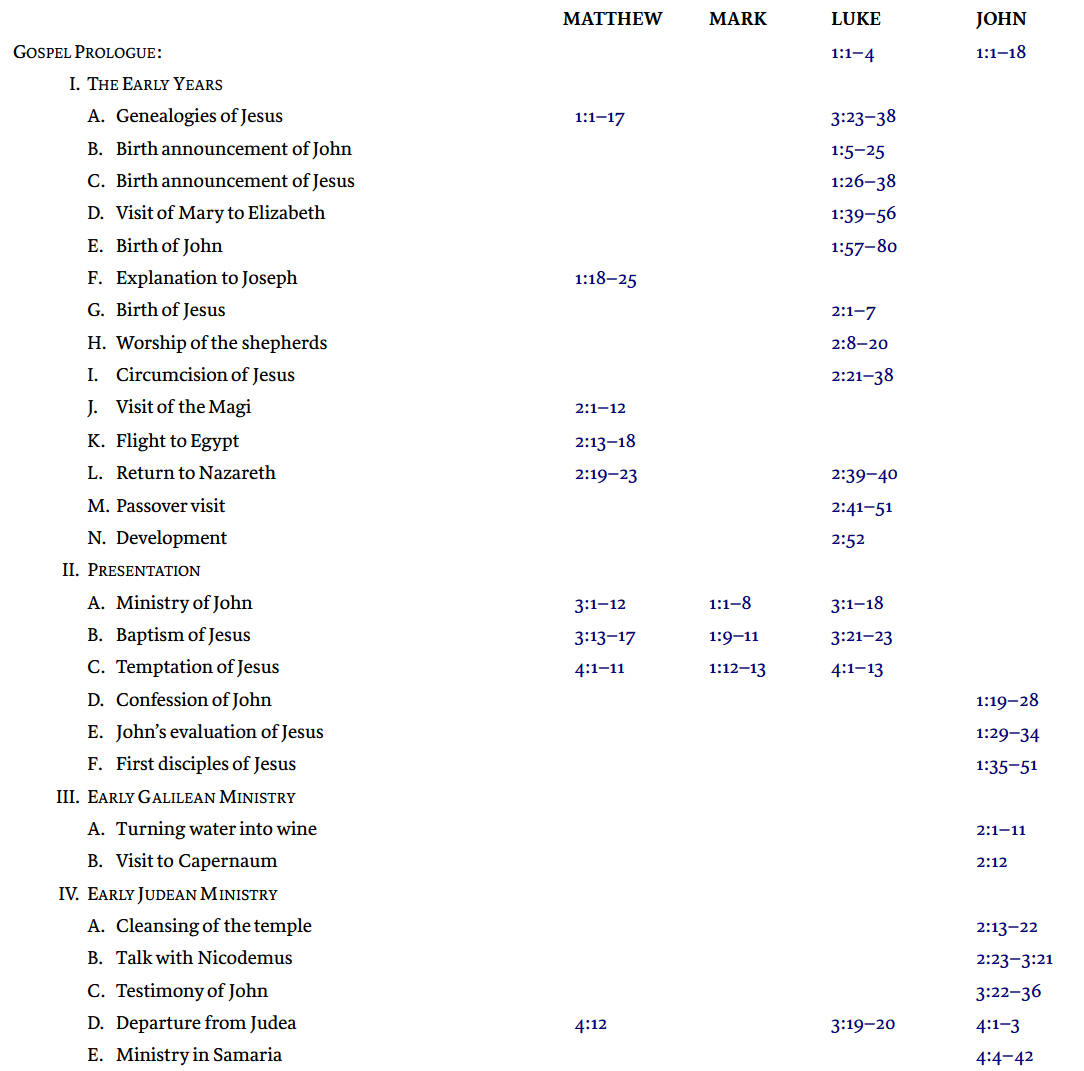

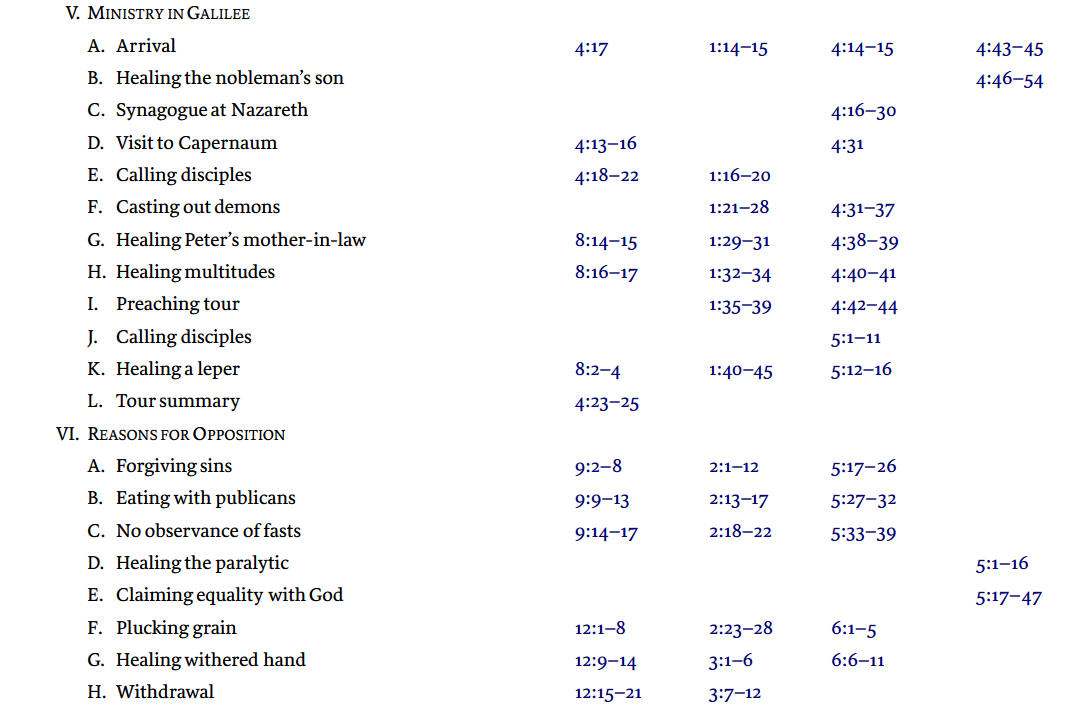

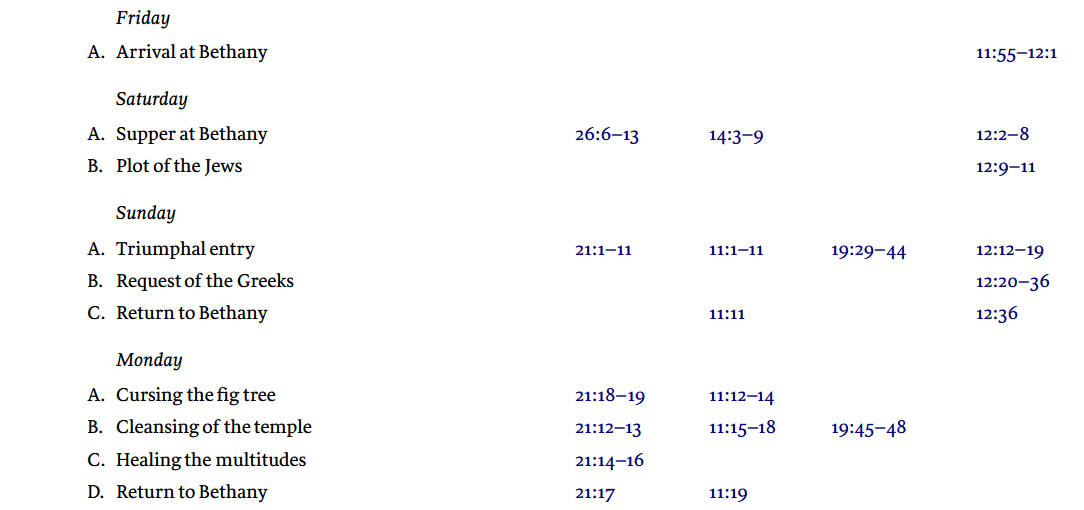

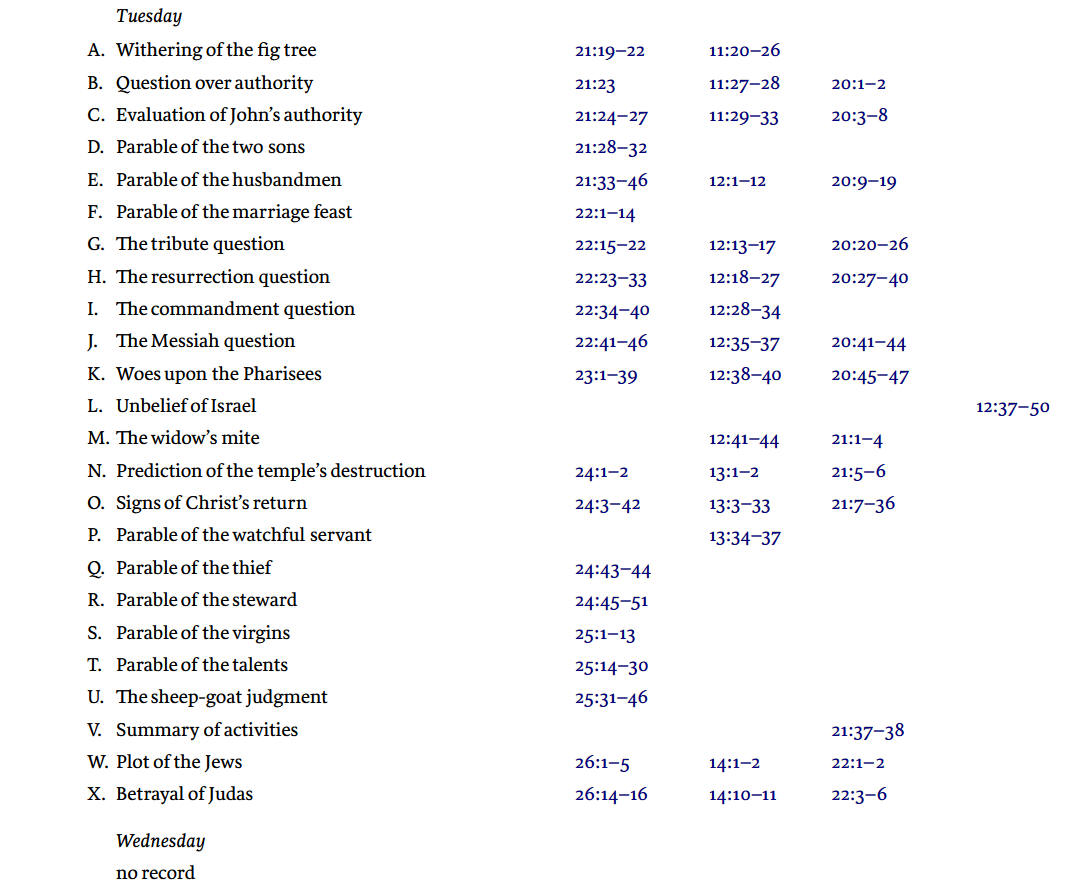

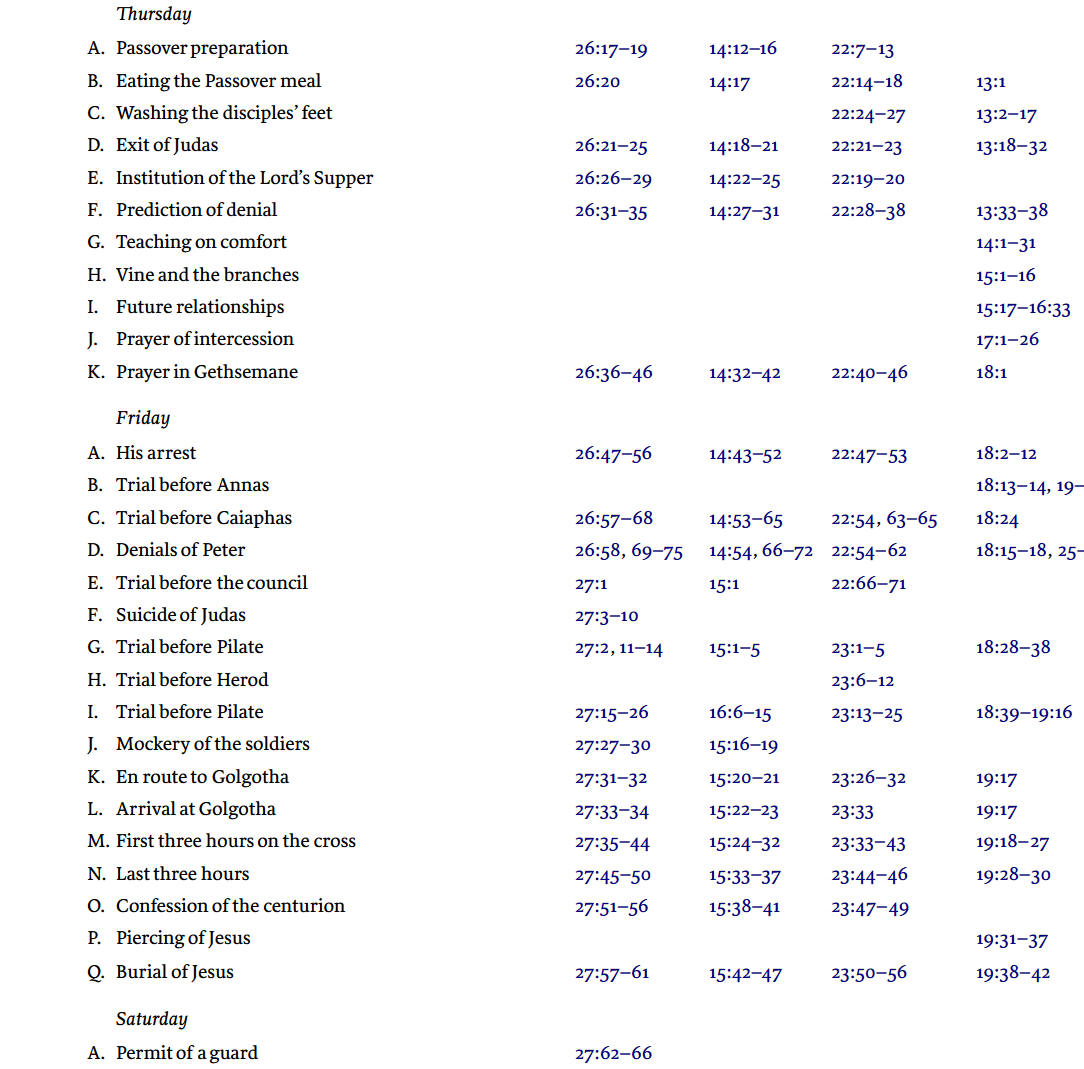

To follow Christ’s earthly ministry from His incarnation to His ascension, one must harmonize the Gospels into a coherent whole. At times, this is difficult to do. Insufficient data are available to make a firm judgment about the exact time that an event occurred. However, the general movement of Christ’s life can be expressed. The following outline is one attempt to correlate the many paragraphs of the four Gospels into a logical, chronological sequence.

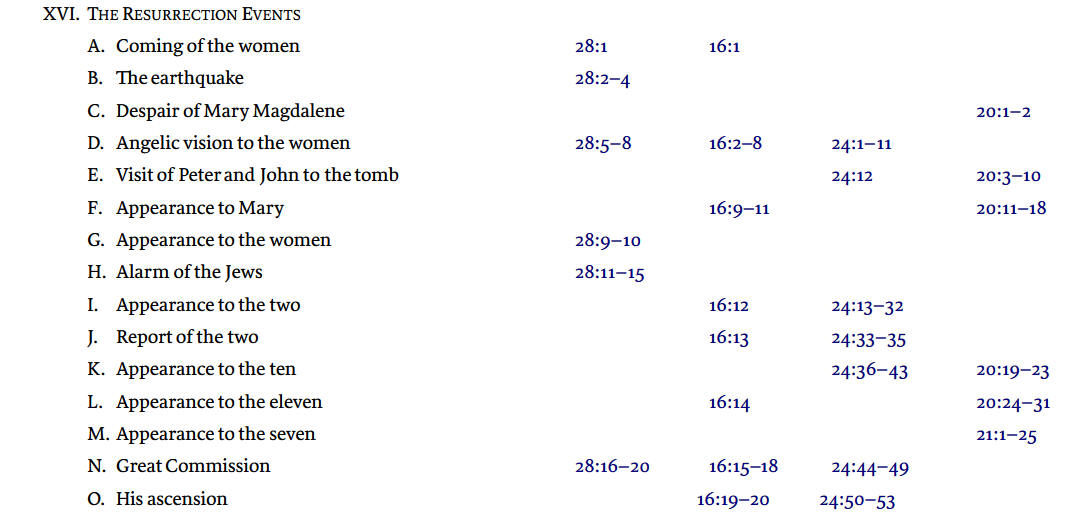

A quick scan of the above chart will show the selective purposes of the respective writers. Only a few major events were recorded by all four: the feeding of the five thousand, the triumphal entry, and the passion week. Although only John recorded the teaching emphases of the Upper Room Discourse, he completely omitted two major addresses: the Sermon on the Mount and the Olivet Discourse. Luke paid special attention to Christ’s ministry in Perea. Since all four spent much time on Christ’s last week, with the real focus on His death and resurrection, this is what they deemed to be the major purpose of His incarnation. He came to conquer sin and death through His crucifixion and resurrection.