1 KINGS

Harry E. Shields

INTRODUCTION TO 1 AND 2 KINGS

Kings presents the history of Israel’s monarchy, in the final days of the united kingdom and the later division into Israel and Judah. The book of 1 Kings opens at the end of the reign of David, Israel’s greatest king. The deportation to Babylon of Jehoiachin, Judah’s last king, closes the book of 2 Kings. The time span of the two books is a little more than 400 years (971–586 BC).

These historical narratives of Israel and Judah include interaction with the surrounding nations, the disasters of following false prophets, and the tragic Babylonian captivity. These books are a record of events in fulfilling God’s promise of blessing for obedience (Dt 17:14–20) and judgment for disobedience (Dt 28–29). During the monarchy the prophets, particularly Elijah, Elisha, and Isaiah, proclaimed God’s message. First and 2 Kings reveal God’s faithfulness to His Word and His people. They are books of theological truth and great spiritual issues which ultimately remind Israel of the Davidic covenant (see 2Sm 7:12–16), the failure of all the kings in fulfilling it, and the resulting encouragement for Israel to keep looking for the coming Son of David, the messianic King.

Author. The books of Kings give no indication of the author’s identity. However the style and word choice, recurring themes, and literary patterns in the book support the historic position of a single author. Rabbinic tradition ascribed authorship to Ezra or Ezekiel. The Babylonian Talmud says it was written by Jeremiah, since 2Kg 24:18–25:30 is exactly the same as the last chapter of Jeremiah (Jr 52). The actual writer is uncertain; however some facts about the author can be learned from the text.

It is clear that the author of Kings was familiar with the biblical text and other Jewish writings and referred to them in the composition of Kings. He referred to the "book of the acts of Solomon" (1Kg 11:41). He also referred to the "Book of the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel" (cf. 1Kg 14:19; 15:31; 16:5, 14, 20, 27; 22:39; 2Kg 1:18; 10:34; 13:8, 12; 14:15; 15:6, 11, 15, 21, 26, 31) and the "Book of the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah" (cf. 1Kg 14:29; 15:7, 23; 22:45; 2Kg 8:23; 12:19; 14:18, 28; 15:36; 16:19; 20:20; 21:17, 25; 23:28; 24:5). These Chronicles are not the OT books of 1 and 2 Chronicles but were official court records on the monarchy, no longer extant. Therefore the unidentified human author drew on a variety of secular records to record inspired history from God’s perspective.

Some critical scholars have suggested Kings had multiple author/editors from various time periods in Israel’s history who recorded events over this 400-year span from Solomon to Jehoiachin. Then a later editor added his own historical details and smoothed out rough transitions in the ultimate production of 1 and 2 Kings. The primary problem with multiple-author theories is that they do not provide sufficient evidence to explain the books’ consistency in presenting a unified theological perspective or linguistic structure. Nor do they explain how these various editors were able to pass information along for a final composition, especially with so many supposed editors involved over several hundred years.

Therefore, the viewpoint of this commentary is that a single author wrote during the time of the exile, compiling what is known today as 1 and 2 Kings. This unidentified author drew on a variety of secular sources to record Israel’s history. The people of Israel needed to understand theologically why they went into exile. Furthermore, all the failed kings of Israel and Judah reminded them to keep looking for the Davidic King, the Messiah, who was yet to come.

Date. The date of composition, like the author, is difficult to ascertain. Nothing is stated in 1 or 2 Kings that pinpoints an exact date of writing.

Internal evidence, however, indicates the books were written during the exile. One piece of evidence is the last recorded event in 2 Kings, the release of Jehoiachin from prison to live out his life in Babylon. This occurred in the 37th year of his exile (cf. 2Kg 25:27–30; 560 BC). However, there is no mention of the return from Babylon, indicating the book was written while the Jewish people were still in captivity.

A second support for dating the books to the time of the exile is the phrase "to this day," which appears 13 times throughout the books (cf. 1Kg 8:8; 9:13, 21; 12:19; 2Kg 2:22; 8:22; 10:27; 14:7; 16:6; 17:34, 41; 20:17; 21:15). The phrase is significant because it describes a variety of situations and historical markers that were still in place or practice at the time of the writing. Again a specific date is not given, but internal evidence indicates that the writing had to be sometime after those events occurred, but not so far distant that they were no longer recalled. A date sometime during the exile, but prior to the return, best fits with the events described in 1 and 2 Kings. Therefore, a probable date for the writing of the books is between 560 and 550 BC.

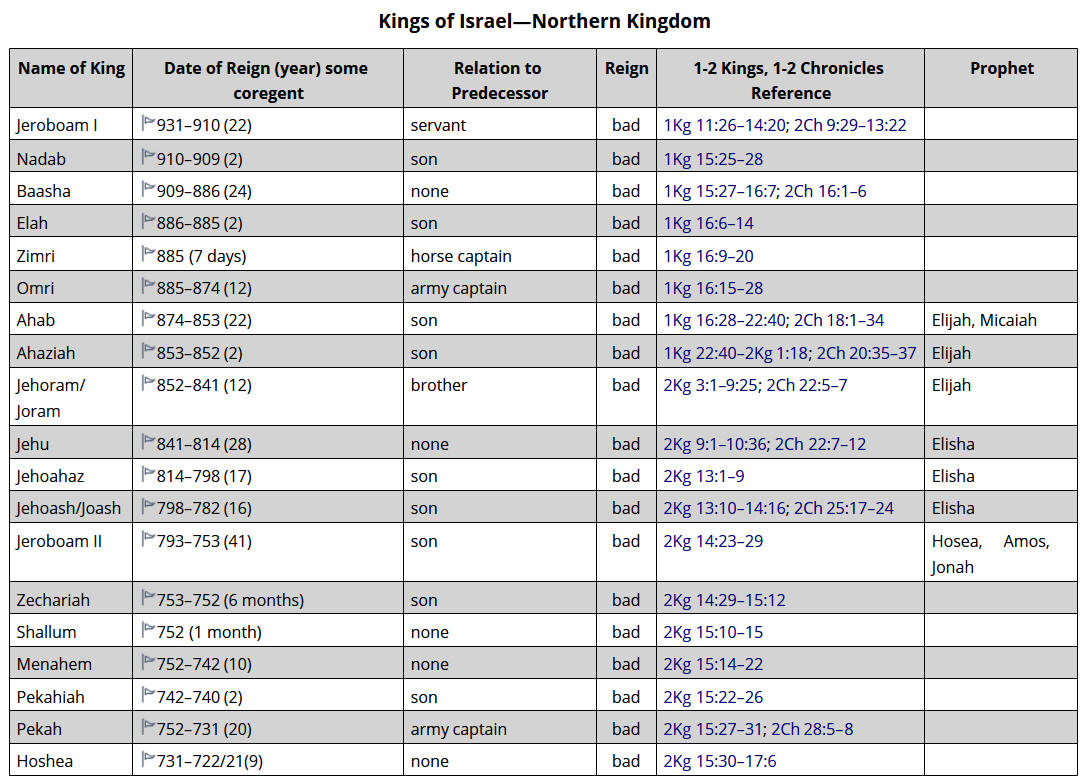

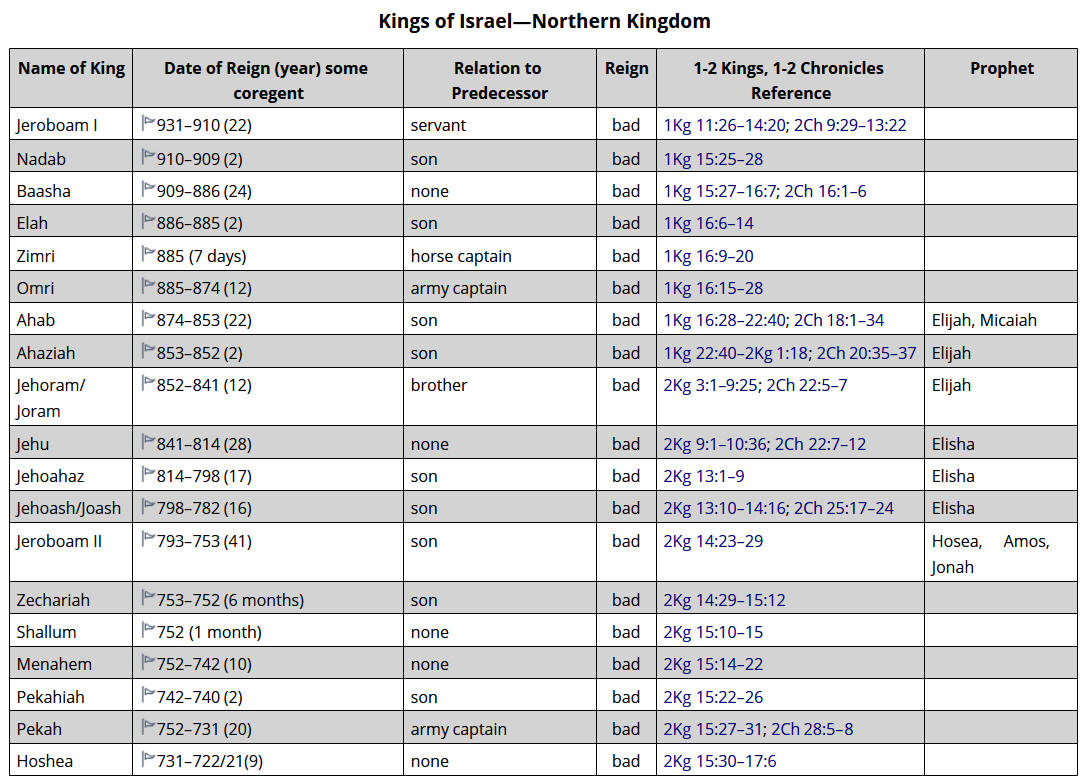

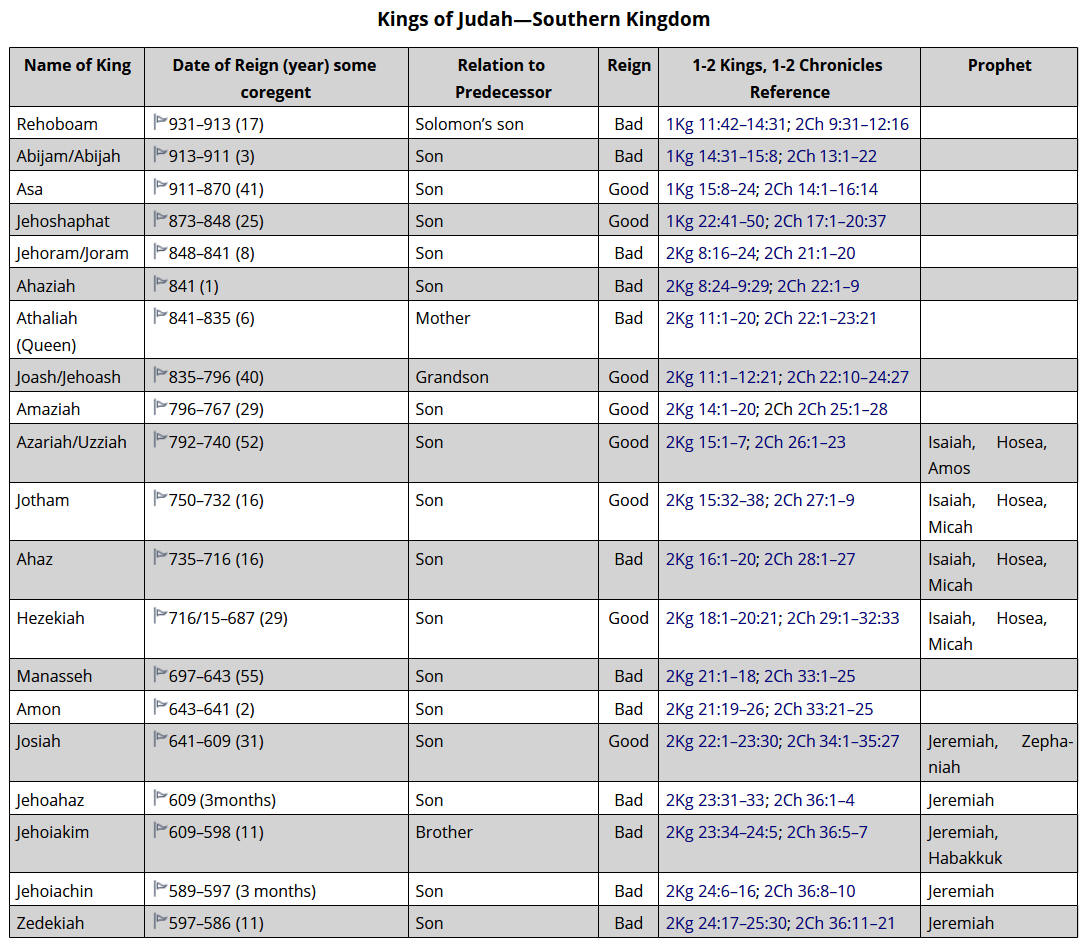

Key dates in Israel’s history are woven into the text: David died and Solomon became king in 971 BC; the kingdom was divided in 930 BC; the northern kingdom fell to Assyria in 721 BC; Judah fell to Babylon in 586 BC. However, an exact coordination of the kings of Israel and the kings of Judah can be confusing, despite chronology such as "in the third year that Jehoshaphat the king of Judah came down to the king of Israel …" (1Kg 22:2). This can be resolved in some cases by understanding coregency or vice-regency of kings. Also, Judah and Israel used two different systems of determining when the reign began, and even this system was sometimes altered over the years. Finally, Judah and Israel began their calendar years at different times, so the beginning of the new year does not coincide. (For a detailed discussion of this see, Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, rev. ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.) The accounts of the reigns of the kings of Judah and Israel often alternate throughout the two books of Kings, with more details given about some of the monarchs and very little detail given about others. The dates and years of the reigns of the kings, along with the key parallel passages in 2 Chronicles, are included in the commentary.

Recipients. The recipients of 1 and 2 Kings are not specifically stated. However, the content and message of the book suggests it was written to the faithful remnant of Jewish people who had gone into captivity. The message of the book explains how and why the nation went into captivity, because of their failure to follow the Lord. It also presents God’s faithfulness to His covenant to David to preserve a faithful remnant (cf. 2Sm 7:8–17). Although all of the kings of Judah had ultimately failed to fulfill the Davidic promise, the implication is that the people should keep looking forward for the messianic King, the greater Son of David.

Purpose and Theme. The historical narrative of Kings goes beyond a simple historical record of the 19 kings of Israel (all bad) and the 20 kings of Judah (only eight good—Asa, Jehoshaphat, Joash/Jehoash, Amaziah, Jotham, Azariah/Uzziah, Jotham, and Hezekiah). First, for the Jewish people in Babylon in 560 BC, and for the later Jewish community, reading Kings would provide insight into their circumstances, explaining the cause of the Babylonian conquest. The nation was taken into captivity for their wicked practice of idolatry: setting up a corrupted worship of the Lord with the golden calves in the northern kingdom, worshiping the gods of the pagan nations around them on the high places and in Jerusalem, and even sacrificing their children to Molech. After the return from exile, Israel would never again practice idolatry.

Second, these books are designed to reveal that each king failed, even the good kings of Judah, to be the ultimate heir to the Davidic throne promised by God in the Davidic covenant (cf. 2Sm 7:8–17). The messianic Son of David was yet to come. Furthermore, an understanding of Kings would give the Jewish people, and all readers up to today, renewed opportunity to fear God, live in devotion to Him, and look for the messianic King.

Background. The two books of Kings were originally viewed as one book in the Hebrew canon, called melakim (Hb. "kings"). The LXX (250 BC) divided both Samuel and Kings into two books most likely to make the length of the texts more manageable. The LXX referred to 1 and 2 Samuel as the "First and Second Reigns," while 1 and 2 Kings became the "Third and Fourth Reigns." The LXX division was quickly adopted by the Hebrew text and all subsequent translations.

The books of 1 and 2 Kings are similar in many ways to 1 and 2 Samuel. All four books were written primarily as historical narrative, but include the message of the prophets to the nation of Israel. In the Hebrew cannon, 1 and 2 Kings are placed with the last of the Former Prophets (Joshua, Kings, and Samuel), emphasizing the prophetic element of the books. The English canon places Kings between Samuel and Chronicles, thus emphasizing the historic element of these books.

The Latter Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel) also have a close connection with Kings in that 1 and 2 Kings provide the historical framework for all that the Latter Prophets proclaim. Both Kings and Chronicles cover Israel’s history, yet they have different emphases. The books of Kings include details of all the kings from both the united and divided kingdoms. However, Chronicles focuses on the house of Judah during the Davidic monarchy. The northern kingdom of Israel is mentioned in Chronicles only in its relationship with Judah.

Note that equal length is not given to each of the kings identified in 1 and 2 Kings. The writer went beyond describing the various details of history to identify the spiritual condition of each king. Some of those spiritual conditions had great impact on the nation and were more important than others, earning more space in the text. After Solomon’s reign the various kings were described by a fairly consistent sixfold formula: (1) the time of a king’s ascension in relation to another king in Israel or Judah, (2) the length of the king’s reign and the place of his capital, (3) the name of the king’s mother in the case of the Judean kings, (4) a statement about whether the king was good or evil in the Lord’s sight, often in comparison to David, (5) the source of further information about the particular king described, and (6) the name of the person who succeeded the king (Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible Book by Book [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002], 93).

The charts "Kings of Israel" and "Kings of Judah" provide an overview of the united monarchy, the kings of Judah and Israel. They include the years of reign and the text that records their history.

OUTLINE FOR 1 AND 2 KINGS

I. The United Kingdom under Solomon (1Kg 1:1–11:43)

A. Solomon Anointed and Establishes Kingdom (1Kg 1:1–2:46)

B. Solomon’s Wisdom, Building, and Success (1Kg 3:1–10:29)

1. Solomon Given Wisdom by the Lord (1Kg 3:1–28)

2. Solomon Wisely Organizes His Kingdom (1Kg 4:1–34)

3. Solomon’s Building Programs: The Temple and Other Structures (1Kg 5:1–8:66)

a. Solomon’s Alliance with King Hiram and Organization of Workers (1Kg 5:1–18)

b. Solomon Builds the Temple and His Palace (1Kg 6:1–7:51)

c. Solomon Dedicates the Temple (1Kg 8:1–66)

4. Solomon’s Warning from the Lord (1Kg 9:1–9)

5. Solomon’s Splendid Kingdom (1Kg 9:10–10:29)

C. Solomon’s Divided Heart and Spiritual Decline (1Kg 11:1–43)

II. The Divided Kingdom: Northern Israel and Southern Judah (1Kg 12:1–2Kg 17:41)

A. Rehoboam of Judah and Jeroboam of Israel (1Kg 12:1–14:31)

1. Rehoboam’s Reign: Foolish Choices and Their Consequences (1Kg 12:1–19)

2. Jeroboam’s Coronation as King of Israel (1Kg 12:20–24)

3. Jeroboam’s Self-Deception and Sinful Choices (1Kg 12:25–33)

4. Jeroboam, God’s Word, and Spiritual Rebellion (1Kg 13:1–34)

5. The Consequences of Jeroboam’s Disobedience (1Kg 14:1–20)

6. Rehoboam’s Reign in Judah (1Kg 14:21–31)

B. The Kings of Judah and Israel until the Fall of Israel to Assyria (1Kg 15:1–2Kg 17:41)

1. Abijam of Judah: A Bad King (1Kg 15:1–8)

2. Asa of Judah: A Good King (1Kg 15:9–24)

3. From Nadab through Omri: Increasing Spiritual Decline in Israel (1Kg 15:25–16:34)

4. Ahab and the Prophet Elijah: The Supremacy of God over Nature (1Kg 17:1–22:40)

a. Elijah and the Prophets of Baal (1Kg 17:1–18:46)

b. Elijah Fears for His Life and Is Comforted by the Lord (1Kg 19:1–21)

c. Ahab and God’s Supremacy over Military Power (1Kg 20:1–43)

d. Ahab Covets Naboth’s Vineyard and Learns of God’s Justice (1Kg 21:1–29)

e. Ahab Confronted by the Prophet Micaiah: God’s Supremacy over Plans (1Kg 22:1–40)

5. Jehoshaphat of Judah: A Good King (1Kg 22:41–50)

6. Ahaziah of Israel: Elijah, and God’s Supremacy over Health (1Kg 22:51–2Kg 1:1–18)

7. Elisha, Prophet to the Northern Kingdom (2Kg 2:1–6:23)

a. Elisha Given the Prophetic Office of Elijah (2Kg 2:1–25)

b. Elisha Confirms His Authority (2Kg 3:1–27)

c. Elisha Performs Miracles to Substantiate His Message from God (2Kg 4:1–6:23)

(1) The Miracle of the Widow’s Oil (2Kg 4:1–7)

(2) The Miraculous Healing of the Shunammite Woman’s Son (2Kg 4:8–37)

(3) The Miracle of Healing the Poison Stew (2Kg 4:38–41)

(4) The Miracle of the Feeding of a Hundred Men (2Kg 4:42–44)

(5) The Miraculous Healing of Naaman the Leper (2Kg 5:1–27)

(6) The Miraculous Recovery of the Axe Head (2Kg 6:1–7)

(7) God’s Miraculous Protection of Elisha (2Kg 6:8–23)

8. Elisha Predicts the Siege of Samaria Will End (2Kg 6:24–7:20)

9. Elisha Carries out the Prophecies Originally Spoken through Elijah (2Kg 8:1–9:13)

10. Jehu of Israel: A Bad King Who Takes Actions that Fulfill Prophecy (2Kg 9:14–10:36)

11. Athaliah and Joash of Judah: A Bad Queen and a Good King (2Kg 11:1–12:21)

12. Jehoahaz and Jehoash of Israel: Bad Kings in the Last Days of Elisha (2Kg 13:1–25)

13. Amaziah of Judah: A Good King; and Jehoash of Israel: A Bad King (2Kg 14:1–22)

14. Jeroboam II of Israel: A Bad King (2Kg 14:23–29)

15. Azariah (Uzziah) of Judah: A Good King (2Kg 15:1–7)

16. Zechariah, Shallum, Menahem, and Pekahiah of Israel: All Bad Kings (2Kg 15:8–26)

17. Pekah of Israel: A Bad King (2Kg 15:27–31)

18. Jotham of Judah: A Good King (2Kg 15:32–38)

19. Ahaz of Judah: A Bad King (16:1–20)

20. Hoshea of Israel: A Bad King and the Fall of the Northern Kingdom (2Kg 17:1–41)

III. The Kingdom of Judah after the Fall of Israel (2Kg 18:1–25:30)

A. The Kings of Judah Prior to the Babylonian Invasion (2Kg 18:1–23:30)

1. Hezekiah of Judah: A Good King (2Kg 18:1–20:21)

2. Manasseh and Amon of Judah: Two Bad Kings (2Kg 21:1–26)

3. Josiah of Judah: A Good King (2Kg 22:1–23:30)

B. The Last Kings of Judah Prior to the Babylonian Captivity (2Kg 23:31–25:7)

1. Jehoahaz and Jehoiakim of Judah: Two Bad Kings (2Kg 23:31–24:5)

2. Jehoiachin of Judah: A Bad King (24:6–16)

3. Zedekiah of Judah: A Bad King (24:17–25:7)

C. The Fall of Judah and Jerusalem (2Kg 25:8–30)

COMMENTARY ON 1 KINGS

I. The United Kingdom under Solomon (1Kg 1:1–11:43)

The book begins with the transfer of the monarchy from David to Solomon and the latter’s subsequent decisions in securing his reign over all Israel. Although he met with internal challenges from his brother Adonijah, Solomon soon learned that God alone had authority over who would lead His nation (cf. Ex 19:5–6). In addition, Solomon learned that the overwhelming task of leadership required more than human skill and expertise. He, like all leaders in Israel, would need the supernatural wisdom of God, if God’s purposes were to be accomplished. And to carry out his father David’s wishes, Solomon set out to build an earthly dwelling place for the Lord. But in the end Solomon’s greatest accomplishments and his great wisdom would be overshadowed by his halfheartedness, led away by multiple pagan wives to worship other gods.

A. Solomon Anointed and Establishes His Kingdom (1Kg 1:1–2:46)

1:1–4. In typical narrative fashion a tension is established at the outset of 1 Kings, as King David was old, advanced in age, approaching seventy, and a new king would be required (cf. 2Sm 5:4; Ps 90:10). His strength and health in decline, the reign of Israel’s greatest king was coming to an end. David’s servants did everything in their power to care for the elderly monarch, but because of old age, and perhaps illness, he could not keep warm. So they sought out a young virgin to attend the king and become his nurse (v. 2). She may have been selected because she was old enough for care for an elderly person, but was not yet married with responsibilities to care for her own family. Her duties were not specified, other than to keep David warm, perhaps being sure he was kept covered with the duties of a constant attendant. The Hebrew term ‘amad for "attend" literally means "to stand before," or in this context, "to serve or nurse" the king. Even though Abishag the Shunammite … was very beautiful and served David, the king did not cohabit with her (v. 4).

1:5–7. David’s imminent death quickly became known to many people in the royal household. As a result, Adonijah the fourth son of David with his fifth wife Haggith (cf. 2Sm 3:2–5; 1Ch 3:2) sought to make himself king (v. 5). David’s older sons Amnon, Absalom, and Chileab (cf. 2Sm 3:3) were already dead (cf. 2Sm 13–18), so Adonijah exalted himself, saying, "I will be king." The Hebrew verbal form for "exalted" reveals that this was not a onetime event, but an ongoing activity on Adonijah’s part ("he kept exalting himself"). His brazen behavior was fueled by his father’s failure to never cross him (v. 6). This is yet another time in David’s life, as with Absalom, when either from negligence or guilt over previous sins he allowed a son to go undisciplined. As a result, Adonijah behaved like a king in waiting (he prepared for himself chariots) and allied himself with an entourage of fifty men (v. 5). Also he conspired with Joab, David’s military commander who had served faithfully for years (cf. 1Sm 26:6; 2Sm 2:13; 19:13; 20:10, 23), and Abiathar the priest (v. 7), who joined David after the Saul commanded Doeg to slaughter the priests (cf. 2Sm 22:18–20). Adonijah wanted them to help make him Israel’s next king.

1:8–10. However, Zadok the priest (cf. 2Sm 8:17), Benaiah, one of David’s mighty men (cf. 2Sm 8:18; 23:20; 1Kg 2:25), Nathan the prophet (cf. 2Sm 12:1–25), David’s trusted spiritual adviser, and the mighty men who belonged to David were not with Adonijah (v. 8). In a fashion similar to Absalom, another son of David who sought to usurp the throne (cf. 2Sm 15:11–12), Adonijah assumed he would be king and he called for a great celebration. He sacrificed … and he invited people who embraced the idea that he would be a worthy successor. But he did not invite Nathan the prophet, Benaiah, the mighty men (cf. 1Ch 11), and Solomon his brother (v. 10). He excluded these people who he knew would not support his grab for the crown, since they supported David and knew God had revealed to David that Solomon would succeed him as king (cf. 1Ch 22:9–10).

1:11–14. When Nathan, the prophet and David’s faithful adviser (cf. 2Sm 12:1–15; 1Ch 17:1–15), learned of Adonijah’s conspiracy, he organized a plan to use both his own influence and that of David’s wife, Bathsheba (cf. 2Sm 11; 12:24), to preserve what God had revealed years earlier regarding the successor to the Davidic line. Nathan said to Bathsheba, Please let me give you counsel and save your life and the life of your son Solomon (v. 12), for it was probable that Adonijah would kill any rivals to the throne if he became king. Nathan revealed the urgency of the situation by instructing her to Go at once to King David and say to him, ‘Have you not, my lord, O king, sworn to your maidservant … Solomon your son shall be king’ (v. 13). This oath is not recorded elsewhere; however, God told David who his successor would be, and possibly David had shared that news with Bathsheba (cf. 1Ch 22:9–10).

1:15–21. Bathsheba carried out Nathan’s plan (introduced in vv. 11–14). She demonstrated her own respect for David as she bowed and prostrated herself before the king (v. 16). Referring to a previous statement by David, she said, My lord, you swore to your maidservant by the Lord your God, saying, ‘Surely your son Solomon shall be king after me and he shall sit on my throne’ (v. 17). David did not dispute her statement. Bathsheba knew that if Adonijah came to the throne she and Solomon would be considered offenders (v. 21), possibly killed as usurpers of the throne. The Hebrew chatta’ (offenders) is frequently translated "sinner" and has a more secular connotation in v. 21, suggesting someone who is accused of breaking the laws of the state.

1:22–27. Part two of the plan (revealed in vv. 11–14) followed in quick succession. The only difference between Bathsheba’s speech and Nathan’s is that the prophet asked questions of David instead of making direct statements. He asked two diplomatic questions to alert David to the circumstances and motivate him to action: First, My lord the king, have you said, ‘Adonijah shall be king after me, and he shall sit on my throne’? (v. 24). Second, he asked a question implying that David had kept something from two of his most intimate confidants: Has this thing been done by my lord the king, and you have not shown to your servants who should sit on the throne of my lord the king after him? (v. 27).

1:28–31. Following Nathan’s inquiry David acted quickly. He called for Bathsheba and vowed in the strongest terms As the Lord lives … Your son Solomon shall be king after me (v. 30). Taking David at his word, Bathsheba bowed with her face to the ground, and prostrated herself before the king. Trusting David to do the right thing, she simply said, May my lord King David live forever (v. 31).

1:32–40. To demonstrate that Solomon had David’s blessings as king, David’s servants were to have Solomon ride on the king’s mule to Gihon, just outside Jerusalem in the Kidron Valley (v. 33). Then Nathan would anoint him there as king over Israel (v. 34). This would make David’s choice of Solomon known publicly.

A crowd gathered (v. 34). The people were rejoicing with great joy, so that the earth shook at their noise (v. 40). What David announced in the privacy of his bedroom was now known throughout Israel. The response of the people indicated that they approved of David’s choice in making Solomon their new king [970–930 BC; cf. 2Ch 1–9].

1:41–48. The news of Solomon’s coronation soon reached the ears of Adonijah and those who were prematurely celebrating with him (v. 41). The messenger, Jonathan the son of Abiathar the priest, reported what was happening (v. 42). He amplified the certainty and authority of Solomon’s ascension to the throne with four facts: (1) Solomon was made to ride on the king’s mule, which showed David’s authorization of the decree (v. 44). (2) Solomon had been anointed king in Gihon, which signified a public declaration of intent (v. 45). (3) David’s servants had extended a blessing, asking God to make the name of Solomon better than David’s name (v. 47). (4) David bowed himself on the bed, indicating his recognition of Solomon as the new king (v. 47). The evidence was clear to Adonijah: his intentions were rejected and Solomon was to be the legitimate heir to the throne.

1:49–53. In fear for his life, Adonijah fled to the tabernacle. The law provided that anyone seeking asylum could be safe by taking hold of the horns of the altar (cf. Ex 21:12–14). Mercifully, Solomon agreed to let Adonijah live, although he made it clear that Adonijah was to prove that he was a worthy man (v. 52). That is, he was to renounce any claim to the throne and accept Solomon as the rightful king. Adonijah was then led into Solomon’s presence, where he prostrated himself before the king (v. 53).

After Solomon’s anointing as king, the aged King David gave some final advice to the new king. Throughout chap. 2, the narrator made it clear that Solomon "established" his kingdom (vv. 12, 24, 45–46), and this firm establishment was a direct result of God’s plan and intervention.

2:1–4. Realizing the time to die drew near, David, as did Moses (cf. Dt 31:1–8), Joshua (cf. Jos 23:1–16), and Samuel (cf. 1Sm 12:1–2) near their time of death, charged, or gave important instructions to, his successor. The first challenge was for Solomon to be strong by depending on the Lord and His Word (Dt 31:7, 23; Jos 1:6–7, 9, 18) and to show himself a man (v. 2). The phrase "show yourself a man" literally means "to become a man." Solomon was to "become" all a king should be who would fulfill the conditions of Dt 17:14–20 by obeying the law. He was to walk in God’s ways, and keep His statutes … commandments … ordinances … and testimonies (v. 3). These terms are frequently used together for obedience to covenant obligations (cf. 6:12; 8:58; 2Kg 17:37; Dt 8:11; 11:1; 26:17; 28:15, 45; 30:10, 16). When Solomon made himself a man obedient to the law, David informed him that the Lord would carry out His promise of the Davidic covenant (v. 4; cf. 2Sm 7:8–17). In addition, the kind of obedience enjoined by David reflected the conditions God established for fulfilling the Davidic covenant (cf. Ps 132:12), conditions which Solomon ultimately failed to meet.

2:5–6. David’s second challenge for Solomon was to deal with the treacherous Joab. Although he had been a brave soldier in David’s army, he had aligned himself with Adonijah (cf. 1:7). During his years of service to David, Joab often took matters into his own hands and usurped the will of King David. For instance, as David was seeking to unite his army with Saul’s forces, Joab killed Saul’s commander Abner in violation of a peace treaty David had enacted with Abner (cf. 2Sm 3). Also, Joab rashly executed Amasa, David’s commander, for taking too long to return from a military assignment (cf. 2Sm 20). David told Solomon to exercise justice according to his wisdom, and not to let Joab’s gray hair go down to Sheol in peace (cf. 2:28–35).

2:7. David then told Solomon to be kind to the sons of Barzillai. This family had assisted David when he fled from the attempted coup of Solomon’s older brother, Absalom (cf. comments on 2Sm 19:31–39). David’s counsel was to let them be among those who eat at your table because of the favor they had shown David in a time of great crisis.

2:8–9. Although Shimei seemed to be supporting Solomon, David knew Shimei’s history and warned Solomon to protect himself from treachery. David remembered that Shimei was from Saul’s family, a Benjamite, and had originally opposed David’s kingship and then sided with Absalom against David. Shimei had cursed him with a violent curse (cf. 2Sm 16:5–13) in direct violation of the Mosaic command not to curse a ruler (cf. 2Sm 19:21; Ex 22:28). Later, after David defeated Absalom, Shimei hurried to meet David, pleading for mercy, and David spared his life (cf. 2Sm 19:18–23). Now with Solomon taking the throne, David again saw Shimei as a potential threat and cautioned for the good of Solomon’s kingdom, do not let him go unpunished. Solomon did take action to protect himself from Shimei’s treacheries (cf. 2:36–46).

2:10–12. Here are the first of several summary statements. David’s death was announced—he slept with his fathers and the length of his reign (1010–970 BC). Solomon sat on the throne of David his father, and his kingdom was firmly established.

2:13–18. Even though the kingdom was secure under Solomon’s control, when Adonijah approached Bathsheba … peacefully, he had a suspicious request. Adonijah’s request was tinged with bitterness and remorse as he told her, All Israel expected me to be king; however, the kingdom has turned about and become my brother’s, for it was his from the Lord (v. 15). He then asked her to ask Solomon to give him Abishag the Shunammite, who had been David’s nurse (cf. 1:1–4), as a wife (v. 17). This request recalls a similar plot when Ahithophel advised Absalom to prove his right to the throne by sleeping with David’s concubines (cf. 2Sm 16:21–23).

2:19–22. Apparently Bathsheba was unaware of Adonijah’s ulterior motive, for she presented his desire to marry Abishag to Solomon as one small request (v. 20). However, Solomon saw Adonijah’s treachery immediately, knowing there might be "wickedness" (cf. 1:52). Solomon realized although David had not had sexual relations with Abishag, her intimate contact with the aged king (cf. 1:1–4) would cause her to be regarded by the people as part of David’s harem. Marriage to her would strengthen Adonijah’s claim to the throne (cf. 2Sm 3:7; 12:8; 16:21), so Solomon told his mother, Ask for him also the kingdom—for he is my older brother (v. 22), since many in the kingdom already had supported Adonijah’s claim to the throne as the oldest heir (cf. 1:5–10). Solomon knew that if he granted Adonijah’s request, then his brother’s co-conspirators Abiathar and Joab (v. 22; cf. 1:7) would continue in the plot to seize the throne for Adonijah.

2:23–25. Solomon took swift and decisive action. He swore by the Lord (cf. comments on 1Sm 3:17) that Adonijah had declared his own death sentence (spoken this word against his own life) in making this grab for the kingdom. Solomon realized the Lord had set him on the throne of David his father (v. 24), so he sent Benaiah, David’s military commander who continued this leadership role under Solomon (cf. 1:8–10; 2Sm 3:20), to execute Adonijah.

2:26–27. Solomon dealt with other conspirators who sided with and assisted Adonijah’s plan to take the throne (cf. 1Kg 1:7). He ordered Abiathar the priest to be banished to Anathoth, his hometown three miles east of Jerusalem. Solomon reminded Abiathar that he deserved to die. But Solomon showed him mercy because of his loyalty to David over a number of years (e.g., 1Sm 22:20–23). He dismissed Abiathar from being priest … in order to fulfill the word of the Lord, a prophecy first mentioned regarding Eli’s household (cf. 1Sm 2:27–36.)

2:28–35. It didn’t take Solomon long to deal with a third individual of Adonijah’s co-conspirators (cf. 1:5–10). When the news came to Joab about Adonijah’s fate and Abiathar’s banishment, he fled to the tent of the Lord and took hold of the horns of the altar (v. 28). This was the same tactic Adonijah employed for sanctuary (cf. 1:51). However, the right of asylum did not apply in conspiracy against the king, and Solomon did not extend mercy to him (cf. Ex 21:14). He quickly sent Benaiah to execute Joab (v. 29). The aging Joab was asked to come away from the altar and surrender (v. 30). But he refused, saying, No, for I will die here (v. 30). Not knowing what to do, Benaiah sent word to Solomon of the standoff and asked what to do. Solomon told Benaiah to do as Joab has spoken and fall upon him (vv. 31, 34). Solomon was obeying David’s earlier warning about Joab, to "act according to your wisdom, and not let his gray hair go down to Sheol in peace" (2:5–6). Joab had shed blood without cause when he took the lives of both Abner and Amasa (v. 32; cf. 2Sm 3:27; 20:9–10). After wisely dealing with treachery in his administration, Solomon quickly appointed Benaiah the son of Jehoiada over the army in place of Joab, and the king appointed Zadok the priest in place of Abiathar (v. 35).

2:36–38. The final enemy about whom David warned Solomon was Shimei (cf. comments on 2:8–9), who cursed David when he was fleeing from Absalom and then became a reluctant ally when David returned to his palace. Solomon called for Shimei and offered him a plan of safety for life, as long as Shimei stayed within the boundary set by the king. He told Shimei to build … a house in Jerusalem and live there, and do not go out from there to any place (v. 36). However, on the day Shimei went beyond the brook Kidron, just east of Jerusalem before the Mount of Olives, he would be treated as an enemy and know for certain that you shall surely die (vv. 37–38). Keeping Shimei within the city of Jerusalem would allow Solomon to keep an eye on him and would prevent Shimei from gathering conspirators against Solomon.

2:39–46. Although Shimei agreed to the plan, after three years, when two of Shimei’s servants ran away to Gath, the region of Israel’s enemy, the Philistines (v. 39; cf. 1Sm 17), Shimei ignored his agreement with Solomon, went to Gath, and brought the escaped servants back to Jerusalem. He could have sent another servant to get the runaways, but foolishly took this opportunity to seemingly justify a trip to enemy territory beyond the limitation of his house arrest. When Solomon learned of the violation he summoned Shimei (v. 42) and reminded him of the oath of the Lord (vv. 41–43). Solomon also reminded Shimei of his past sins against David. So Solomon commanded Benaiah to execute Shimei (v. 46).

The section concerning the enemies of Solomon and of the house of David concludes with good news: the throne of David shall be established before the Lord forever. God was at work to fulfill His covenant and subsequently bless the reign of Solomon as promised (cf. 1Kg 1:47–48; 1Ch 22:9–10).

B. Solomon’s Wisdom, Building, and Success (1Kg 3:1–10:29)

These chapters portray the reign of one of the greatest monarchs of all time. Chapters 1 and 2 show how Solomon became David’s successor, but chaps. 3 and 4 reveal the reasons behind his legitimacy to the throne. His building programs are outlined in chaps. 4–9, with details about the building of the temple. Highlights of Solomon’s magnificent reign include the visit from the Queen of Sheba and the descriptions of his splendors in chap. 10.

1. Solomon Given Wisdom by the Lord (1Kg 3:1–28)

3:1. Although Solomon’s kingdom was established (cf. 2:46) and he would receive great wisdom from the Lord (cf. 3:6–15), he foolishly began his reign with the first of many marriages to foreign women who would eventually lead him astray into pagan worship (cf. 1Kg 11:1–8). Solomon formed a marriage alliance with Pharaoh. The clause literally reads "made himself a son-in-law of Pharaoh." Marriage alliances were common in the ancient world for a military and trade advantage; however they had been forbidden by the Lord (cf. Dt 17:17).

3:2–3. Although Solomon loved the Lord, he (along with the people of Israel who were sacrificing) sinned when he sacrificed and burned incense on the high places, pagan places of worship, instead of the one prescribed place, the tabernacle (cf. Dt 17:3–5).

3:4–5. At this time Solomon had a personal encounter with the Lord at Gibeon when he went to sacrifice there. Gibeon was a Levitical city about five miles from Jerusalem (Jos 18:25; 21:17). It was referred to as the great high place because the tabernacle of the Lord was there (v. 4; cf. 1Ch 16:39–40; 21:28–29; 2Ch 1:3, 5–6). Here in a dream God graciously appeared the first of two times in Solomon’s life (cf. 9:2) and posed the most significant offer he would ever be given: Ask what you wish me to give you. Solomon’s answer would change the course of his administration for good and for the good of the people.

3:6–7. Solomon responded to God by acknowledging that He had shown great lovingkindness to his father, David. He also hinted that the Davidic covenant was being fulfilled in him. But he quickly made his request, saying, Yet I am but a little child; I do not know how to go out or come in. This expression (Hb. na’ar means "immature person") reflected Solomon’s youth and his virtual inexperience, not his chronological age. Since he reigned 40 years (970–930 BC) and did not die at a remarkable old age, he probably became king between the ages of 20 and 30 (cf. 1Kg 11:42–43). He felt overwhelmed by all that was placed on his shoulders in administering this kingdom.

3:8–9. Solomon proceeded to make his request, and God followed with an answer. First, Solomon identified himself as God’s servant, and one of Your people which You have chosen, reflecting the Lord’s unique relationship with the Jewish people (cf. Gn 12:1–3; Dt 7:7–8). He asked for an understanding heart to judge Your people to discern between good and evil. The word translated "understanding" comes from the Hebrew term shome’ and can also be translated "hearing." Throughout the OT the words "hearing" and "obedient" were often intertwined. So what Solomon was asking for was the ability to "obey" what God had said in the law, and then to be able to distinguish between good and evil for the good of the Lord’s people.

3:10–15. God responded that He had heard Solomon’s prayer and that He would bless the new king. Solomon’s request was pleasing to God because he had not asked for [him]self (v. 11), but was focused on the needs of the people to have discernment to understand justice (v. 11). God promised to give Solomon the discerning heart he requested, and He also promised that there would be no one like you before you, nor shall one like you arise after you (v. 12). God also promised Solomon he would have the very things he did not request—both riches and honor (v. 13).

Yet there was one conditional statement that Solomon would need to hear. It was the kind of condition his successors after him would also have to remember. These blessings would come If you walk in My ways, keeping My statutes and commandments (v. 14). God’s desire was to bless Solomon, but the king was under obligation to obey the Lord in accordance with the stipulations of Dt 17:14–20. When Solomon awakened from his encounter with the Lord, he knew it was a dream, but he also realized God had spoken to him. So as a new act of obedience he went to the ark of the covenant of the Lord in Jerusalem and offered up sacrifices that were given in view of his sin, and also in view of God’s great mercy (v. 15).

3:16–28. Immediately after the Lord gave Solomon great wisdom, the familiar story of the two harlots and the baby is recorded as evidence of King Solomon’s wisdom (v. 16). This was a common procedure to inquire of a monarch in the ancient world and ask him to settle disputes. Both women gave birth to sons on the same day. There were no witnesses of the events that transpired. But in the middle of the night, one of the sons died because, according to one of the women, she [the second mother] lay on it (v. 19). While the other mother slept with the child that was still living, the mother of the dead child came and stole the living child away, replacing the child she took with the dead son (vv. 20–21).

After listening to both women, Solomon shocked the women by asking for a sword and suggesting that he cut the living child in two and give half to each (vv. 24–25). Maternal compassion became evident, along with ruthless evil. It was in the differing response of each woman that Solomon was able to "discern between good and evil" (cf. 3:9). Consequently, he gave the child to the mother who was willing to give up her son rather than see him die. Solomon’s verdict not only impressed these women, but all Israel … feared the king, for they saw that the wisdom of God was in him to administer justice (v. 28). It was confirmation that Solomon was God’s choice to be king and that God was clearly working in his life by giving him great wisdom.

2. Solomon Wisely Organizes His Kingdom (1Kg 4:1–34)

Solomon’s divine wisdom was not only demonstrated in the execution of justice, but also in the way he brought order to the nation over which he was king. Prior to David’s reign and under the leadership of Saul, Israel was little more than a loosely knit tribal confederacy. Under David’s leadership the borders of Israel were expanded to come close to the land promises of the Abrahamic covenant. Captured nations were paying tribute, which brought great amounts of revenue into the nation. Under Solomon more administrative order was implemented.

4:1–6. Following David’s successful reign, Solomon was king over all Israel (cf. 2Sm 8:15) and administered it with a well-organized government. Within Solomon’s court, specific individuals were identified to provide the young king with spiritual, political, and military support. Perhaps Zadok (cf. 1:38) was too advanced in years to oversee the priesthood, so Azariah the son of Zadok was the priest (v. 2). The definite article "the" may indicate that Azariah was the high priest, while Zadok continued to serve in the priesthood. Benaiah replaced Joab as the commander over the army (v. 4). Although Abiathar had been dismissed as a priest by Solomon (cf. 1Kg 2:27), he apparently was given a somewhat emeritus role. It very well could be that some of the people mentioned served transitional roles in the new administration. Clearly, out of his God-given wisdom, Solomon saw a need to bring order to the daily activities of his court.

4:7–19. Solomon arranged for the financial support of his administration. Solomon had twelve deputies over all Israel, who provided for the king and his household (v. 7). These were not the twelve tribes of Israel, but administrative areas, perhaps based on agricultural productivity. Each of the twelve deputies had to provide for a month in the year (v. 7), as a means of providing equity in caring for the royal needs without overburdening any one area.

4:20–21. Solomon’s reign was closely connected with the provision of the Abrahamic covenant (cf. Gn 12:1–9). The Israelites, Judah and Israel, had multiplied to the extent that they were as numerous as the sand that is on the seashore in abundance (v. 20), and Solomon ruled over the area God had promised.

4:22–28. The extent of Solomon’s wealth is evident in the size of the provision for one day required for his court; one kor equals 10 bushels. So each day he needed 300 bushels of fine flour and 600 bushels of meal, plus hundreds of animals for meat to feed the royal house and administrative staff (v. 23). So Judah and Israel lived in safety, and they enjoyed individual prosperity as well from Dan even to Beersheba, meaning all across the land north to south (v. 25; cf. Jdg 20:1; 1Sm 3:20). Solomon had a military might of 40,000 stalls of horses for his chariots, and 12,000 horsemen (v. 26). However, Solomon’s multiplication of horses, a sign of military might, directly violated the Lord’s command to depend on Him for security, and it would become a great problem in Solomon’s later reign (cf. Dt 17:16; 1Kg 10:26–29).

4:29–34. Solomon was affirmed as having wisdom in the management of his kingdom greater than the men of the east, of Egypt, and the surrounding nations (vv. 30–31). His literary skills were also cited, since he wrote 3,000 proverbs, and his songs were 1,005 (v. 32). Solomon was also noted for his wisdom and expertise in plant and animal sciences (v. 33). As a result, men came from all peoples to hear the wisdom of Solomon (v. 34). Whether they knew it or not, Solomon’s wisdom was really God’s wisdom given to a young king to rule righteously.

3. Solomon’s Building Programs: The Temple and Other Structures (1Kg 5:1–8:66)

a. Solomon’s Alliance with King Hiram and Organization of Workers (1Kg 5:1–18)

Solomon’s wisdom was displayed in the way he administered justice (cf. 3:16–28) and in the way he united the citizens into a highly functioning social unit. In chaps. 5–7 Solomon’s wisdom and glory were put on display in his major building projects, the temple in particular.

5:1–12. News of Solomon’s wise leadership reached Israel’s northern neighbor. Hiram king of Tyre sent his servants to Solomon when he heard that they had anointed him king in place of his father. Hiram had always been a friend of David and had provided the wood for the construction of David’s palace (cf. 2Sm 5:11). David had not been allowed by the Lord to build His house, the temple (v. 3), but now Solomon would build a house for the name of the Lord my God (v. 5). Solomon wanted only the best wood for the project, cedars from Lebanon (v. 6). The basis for this first building project was Solomon’s obedience to the Davidic covenant (cf. 2Sm 7:12–13).

Hearing of Solomon’s plans, Hiram affirmed that the Lord had given David a wise son and agreed to do what you desire concerning the cedar and cypress timber (vv. 7–8). Hiram would cut and transport the wood in the form of bundled rafts on the water, and then unload them at a designated site along the Mediterranean coastland. In turn, Solomon’s workers would transport the wood after Hiram disassembled the logs at an appropriate place (v. 9). Payment for the wood and the work of transportation was to be carried out by giving food to my [Hiram’s] household (v. 9). For this great building project the Lord gave wisdom to Solomon to start the construction of the temple. A covenant of peace between Hiram and Solomon sealed the transaction (v. 12).

5:13–18. Gathering resources for the temple was a major task. Solomon organized 30,000 forced laborers to work in relays of 10,000 men per team. The workforce came from all Israel (vv. 13–14). They would spend one month in Lebanon and two months in Israel. Also 70,000 individuals transported materials from their place of origin to a place of preparation, and 80,000 individuals served as stonecutters in the mountains (v. 15). Some of the workers were taken from the descendants of those whom the Israelites were not able to drive out of the land, while others were conscripted Israelites, but Solomon "did not make slaves of the sons of Israel" (1Kg 9:22; cf. 2Ch 8:9).

b. Solomon Builds the Temple and His Palace (1Kg 6:1–7:51)

6:1. The starting date for building the temple has three specific chronological markers associated with it. Scholars debate whether the four hundred and eightieth year was a rounded number or a symbolic expression of the number of generations from the exodus to the time of construction begun here. This brief time reference connects what Solomon was doing with the ongoing work of God’s redemption for Israel, and the nation’s promise from God to dwell in the land. The most important piece of information is that construction started in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel. Most scholars believe that this would have been 967–966 BC. Therefore, a literal reading of the four hundred and eightieth year would make the date of the exodus to be 1447–1446 BC. Along with these two chronological markers is the fact that Solomon started this project in the second month of Ziv (April/May). It took Solomon seven years (seven years and six months) to build the temple (cf. 6:38).

6:2–10. By modern standards the temple was a fairly small worship facility: its length was sixty cubits [90 feet] and its width twenty cubits [30 feet] and its height thirty cubits [45 feet] (v. 2). A porch was in front of the temple, and the temple had several windows, and stories encompassing the walls … around both the nave and the inner sanctuary (v. 5). The stones used in the basic structure were prepared at the quarry, so that no sound of tools was heard in the house (v. 7). The basic structure of the temple indicates from its outward appearance that it was a place of reverence (vv. 5, 8) and functionality (v. 7). The temple was enclosed completely with the construction of a roof or covering of beams and planks of cedar (v. 9).

6:11–13. As the temple was under construction the word of the Lord came to Solomon reminding him of the most important aspect of the house which you are building. Solomon was certainly building a great temple, but God was much more concerned with the condition of the heart—Solomon’s heart, the hearts of his royal descendants, and the hearts of the people. God offered Solomon the following: if you will walk in My statutes and execute My ordinances and keep all My commandments by walking in them, then I will carry out My word with you which I spoke to David your father (v. 12). Obedience to the Mosaic and Davidic covenants was necessary for God to carry out His Word to the king and for Him to dwell among the sons of Israel (v. 13).

This passage plays a significant role in the development of the book’s messianic message. In essence, God was offering Solomon that if he obeyed the Torah completely, God would fulfill the Davidic covenant through him (cf. 2Sm 7:12–16). At this point in the narrative, it appears that Solomon would be the son of David, the Promised One who would build the house for the Lord, who would have an eternal house, kingdom, and throne (cf. 2Sm 7:13). Further, he would go on to build the temple (but not the eschatological, messianic temple the prophets foresaw; cf. Zch 6:11–15; Ezk 40–48). The author’s purpose was to raise the hope that the promise would be fulfilled in Solomon, but then reveal that Solomon would fail. He would multiply pagan wives who would turn his heart away from the Lord and cause him to follow foreign gods.

Clearly, Solomon was not to be the fulfillment of the promise to David. Afterwards, every Davidic king was compared to David, the ideal king, to see if he would be the promised Son of David. And in each case, even those who were deemed "good," the Davidic king would ultimately fail. Thus, at the end of the book of 2 Kings, the only conclusion to be drawn was that the promise to David had not yet been fulfilled. As a result, the message of the books of 1 and 2 Kings would be to keep looking for the fulfillment of the messianic promise to David in the future. In this way, 1 and 2 Kings point to the future with hope for a messianic Son of David who will yet fulfill the messianic promises, build the temple of the Lord (cf. Zch 6:11–15), and have an eternal house, kingdom, and throne.

6:14–18. Following God’s reminder about the importance of obedience, details were given about the interior design and construction of its most revered sections. Solomon took the instructions given to him by his father David (cf. 1Ch 28:11–12) and prepared a structure that pointed to the glory and grandeur of God. The entire interior was covered with cedar and cypress wood, covering all the stone from the floor of the house to the ceiling (v. 15). These wooden paneled walls were also carved in the shape of gourds and open flowers, which pointed to God as the author of all creation. The whole stone building was covered by cedar and there was no stone seen (v. 18).

6:19–36. The most important part of the temple was the inner sanctuary, or the holy of holies, where the ark of the covenant (cf. Ex 25:10–22) would be kept (v. 19). The inner sanctuary was twenty cubits (30 feet) in length, width, and height (v. 20). In the center of the inner sanctuary were two wooden cherubim overlaid with gold. They were placed within the inner sanctuary in such a way that the wing of one cherub would touch one wall and the wing of the other would touch the other wall (vv. 23–28). The walls were also carved with engravings of cherubim, palm trees, and open flowers in both the outer and inner sanctuaries (v. 29). The grandeur of the gold-plated inner sanctuary along with the fact that Solomon overlaid the floor of the house with gold (v. 30), indicates that God was to be seen as exalted and majestic above all other gods. The inner sanctuary was His throne room where He would dwell with His people.

6:37–38. Solomon started temple construction in the fourth year of his reign, in the month of Ziv (cf. 6:1). The construction was completed in the eleventh year, in the month of Bul, which is the eighth month (Oct/Nov 959 BC). So it took the king seven years and six months to finish what he was commissioned by God to do.

7:1–12. Yet the construction of Solomon’s own house took thirteen years, twice as long as it took to build the temple. The contrast in time devoted to the temple versus time spent on Solomon’s private quarters and administrative buildings may indicate that he was already being tempted by his own self-importance (cf. Dt 17:19–20). Solomon’s other building projects included five specific structures, three of which related to his administrative responsibilities as Israel’s king (vv. 2–7). Two of the structures were designed for his own residential needs (vv. 8–12). The house of the forest of Lebanon, meaning it was built from the cedar trees of Lebanon (cf. 5:1–8), was 150 feet long, 75 feet wide, and 45 feet high, and served as an armory (cf. 10:17, 21; Is 22:8).

In addition there was the hall of pillars, which may have been part of a large palace complex (v. 6). This hall or colonnade served as a kind of portico that led into the hall of the throne or the hall of judgment … paneled with cedar, where Solomon rendered verdicts on issues of justice brought before him (v. 7).

The last two buildings are simply described as his house and a house like this hall for Pharaoh’s daughter (v. 8). No detail is given, but Solomon may have gone to great expense and effort to build an individualized home for this wife above all the other women mentioned in 11:1. All five buildings were constructed out of costly stones and cedar beams (vv. 9–12). The complex would have been an impressive sight for the Israelites and foreign visitors to behold (cf. 10:11–13).

7:13–14. After describing the temple building, the inner sanctuary, and Solomon’s palace, the author gave details of the temple furnishings. Solomon wanted the best craftsman, so he sent for Hiram from Tyre. Although they have the same name, this was not King Hiram (cf. chap. 5). This Jewish craftsman who lived in Tyre, also known as Huram-abi, was the son of a Danite woman (cf. 2Ch 2:13–14). He is identified as a widow’s son from the tribe of Naphtali, and his father was a man of Tyre (v. 14). His genealogy is not a contradiction because by Solomon’s time the tribe of Dan had moved north from their original allotment area in central Israel (cf. Jos 19:40–50; Jdg 18) and were incorporated into the general region of Naphtali (cf. Jos 19:32–39), making Hiram’s mother’s tribal identity both Dan and Naphtali. Hiram was filled with wisdom and understanding and skill for doing any work in bronze. This statement parallels the description of Bezalel (cf. Ex 31:1–5; 35:31), who built the tabernacle. The pairing of wisdom and understanding are often used to describe spiritual qualities, not just craftsmanship (e.g., Pr 4:7; 9:10; Is 11:2). A structure fit for the presence of God needed the influence of men who were also empowered by God.

7:15–22. Hiram designed two pillars of bronze about 30 feet high. Both pillars had carefully crafted capitals made for their tops and accompanying lily design (v. 22). But the striking feature of the pillars was that they were given names: Jachin (Hb. "he will establish") and Boaz (Hb. "in him is strength"). The names would serve as a reminder to the king and the citizen/worshiper that it was the Lord who would establish His people in accord with His strength as they lived lives of obedient worship.

7:23–26. Hiram also crafted a large sea, or basin, as a laver for the priests to wash as part of their ceremonial duties (cf. Ex 30:18–21; 40:30–32; 2Ch 4:6). It was ten cubits around and five cubits high (about 15 feet across and seven and one-half feet high, v. 23) and stood on twelve oxen (v. 25). This massive basin held two thousand baths, about 11,000 gallons of water (v. 26).

7:27–39. Hiram also crafted ten stands of bronze moveable on four bronze wheels, each one six feet square and about five and one-half feet high (four cubits square and height of three cubits). They were decorated with lions, oxen, and cherubim (vv. 27–30). On top of the stand was a basin, which held forty baths of water (v. 38), 230 gallons, used in the ceremony of the temple for purification.

7:40–47. Although no specific detail is given regarding their functions in the temple, Hiram made the basins and the shovels and the bowls used by the priests in temple service. The impressive nature of Hiram’s work was seen in the statement: Solomon left all the utensils unweighed, because they were too many; the weight of the bronze could not be ascertained (v. 47).

7:48–51. The temple built by King Solomon, a permanent structure similar in design and parallel in purpose to the temporary tabernacle (cf. Ex 40), was now complete and ready to be used in worship of the true King, God Almighty.

c. Solomon Dedicates the Temple (1Kg 8:1–66)

With the temple construction completed, Solomon dedicated the temple to the worship of the Lord. The focus of the dedication was the greatness of God, and the fulfillment of His promises made to David and now completed under Solomon’s reign (cf. 8:20–21). Solomon’s desire was that "all the peoples of the earth may know that the Lord is God; there is no one else" (8:60).

8:1–2. For the sacred assembly Solomon called in the elders … all the heads of the tribes and the leaders of the fathers’ households. Everyone in Israel, from the leadership to each family, was to be represented at the event. The focus of the assembly was to bring up the ark of the covenant of the Lord to the temple. It had been in the house of Obed-edom, the Gittite (2Sm 6:10), in the city of David, the part of Jerusalem built on the original Jebusite area, south of the Temple Mount. From now on the ark would reside in the holy of holies in the temple (cf. 2Sm 6:16–17). The dedication occurred at the time of sacred assembly at the feast, in the month Ethanim (Sept/Oct, also known as Tishri) … the seventh month, at the Feast of Booths (cf. Lv 23:33–36).

8:3–9. The ark and all the holy utensils from the tent of meeting (cf. Ex 40), the tabernacle, were brought into the temple by the Levites (vv. 3–4; cf. Nm 3; 4; 7; 2Sm 6:6–7). At the dedication of the temple there was so much sacrificing occurring simultaneously that the sheep and oxen … could not be counted (v. 5). As the priests carried the ark on the poles, it was eventually placed under the wings of the cherubim (vv. 6–8; cf. Ex 25:10–22). If Kings was written or ultimately completed during the time of the exile, then the phrase they are there to this day (v. 8) could not be referring to the existence of these poles at the time of the book’s completion because the temple and its sacred contents were destroyed in 586 BC. However, as noted in Introduction: Date for this commentary, the author used several sources to compile 1 and 2 Kings. House suggests that when the author referred to these sources he used a phrase like "they are there to this day." In that sense the phrase is a kind of "footnote" referring to an original source (Paul R. House, 1, 2 Kings, NAC [Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 1995], 30).

8:10–21. Once the ark was in place, the cloud filled the house of the Lord (V. 10), a phenomenon frequently associated with the Lord’s presence (e.g., Ex 13:21–22; 16:10; 40:33–35; Ezk 10:3–5). Here the manifestation was so overpowering that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud (v. 11). God, Israel’s Great King, had come to dwell with His people. Solomon explained the supernatural phenomenon as a sign of God’s fulfilling His promises to David: Now the Lord has fulfilled His word which He spoke … as the Lord promised (v. 20; cf. 2Sm 7:8–16; 1Ch 22). Solomon also associated the presence of the glory of the Lord with the covenant made with our fathers when He brought them from the land of Egypt (v. 21; cf. Ex 15:1–18). Solomon’s purpose was to remind the people that God had been true to His Word all along.

8:22–26. In view of God’s faithfulness, Solomon offered a lengthy prayer of intercession for himself and his subjects standing before the altar of the Lord (vv. 22–53). He acknowledged the Lord’s uniqueness: God of Israel, there is no God like You. He reiterated God’s faithfulness: keeping covenant … with Your servant, my father David (vv. 23–24).

8:27–30. Solomon also emphasized God’ great power: The highest heaven cannot contain You (v. 27). Yet intercession directed toward the temple was appropriate, since that was where God said, My name shall be there (v. 29; cf. 5:5). God’s character was epitomized by the phrase "My name" (cf. Ex 33:19; Dt 12:5; 2Sm 6:2; 7:13; Ps 61:8). Here Solomon established the Jewish custom of turning toward Jerusalem, the location of the temple, when they pray toward this place and ask God to hear in heaven Your dwelling place; hear and forgive (v. 30; cf. 8:38, 44, 48; Dn 6:10; Ps 5:7).

8:31–40. Solomon interceded on behalf of citizens and underscored their relationship to the Lord as living in the land He gave them (vv. 34, 36, 40; cf. Gn 12:1–9). The people were to depend on Him in legal disputes with one another, coming before Your altar in this house (v. 31), asking that God would hear in heaven and act and judge (v. 32). He also asked for mercy when the nation sinned and were defeated in battle when there is no rain or famine (vv. 33–37). Solomon asked for forgiveness of sin, and for God to teach them the good way in which they should walk (v. 36). He asked that they would fear You (v. 40), recognizing God’s great power and therefore obediently serve Him.

8:41–45. Solomon then prayed for Israel’s relationship with non-Jewish people. First, he prayed for mercy for the foreigner who learns of Your great name (v. 42). This is a prime example of God’s desire for the nations, the Gentiles, in the OT to know the Lord, in order that all the peoples of the earth may know Your name, to fear You, as do Your people Israel (v. 43). Next Solomon prayed for military victory when following the Lord’s direction in battle … whatever way You shall send them, that He would hear their supplication, and maintain their cause (v. 45).

8:46–49. This part of Solomon’s prayer was an instruction and warning that looked to the future regarding Israel’s exile from the land. When they sin and they are taken away captive, an event that occurred almost 400 years later at the Babylonian captivity (586 BC), the people were pray to God toward their land (v. 48) and repent.

8:50–53. Then Solomon asked God to have compassion on the people and listen to them whenever they call to You (v. 52; cf. v. 29; Dn 6:1; Ps 137). However, the prayer was not based on the merit of the king or the people, but on the reality that God had separated Israel from all the peoples of the earth as Your inheritance (v. 53).

8:54–61. With the prayer completed, Solomon turned and blessed the people, saying Blessed be the Lord (V. 56). This benediction had two elements. First Solomon wanted the prayer to be fulfilled so that all the peoples of the earth may know that the Lord is God; there is no one else (v. 60). In that sense his prayer had an outward, evangelistic focus to it. Second, He challenged the people to be wholly devoted to the Lord our God, having an inward spiritual focus (v. 61).

8:62–66. Solomon’s prayer was followed by a series of sacrifices. The number of animals offered up to the Lord was so great that a minor change of venue had to occur. The king consecrated the middle of the court … for the bronze altar that was before the Lord was too small to care for the many offerings (v. 64). Great care and caution were undertaken to ensure that God was given the respect that His holy nature deserved. What started out as the observance of the annual seven-day feast of booths (8:2) ended up lasting for fourteen days (v. 65). However, the ongoing activities were not exhausting to either Solomon or his subjects, because he sent the people away and they blessed the king. They were joyful and glad of heart because they realized that God, their true King, had blessed them from the days their forefathers experienced Him at Sinai to the completion of the great temple (v. 66).

4. Solomon’s Warning from the Lord (1Kg 9:1–9)

Solomon’s reign as king had been magnificent in so many ways. God granted him wisdom beyond his years (cf. 1Kg 3:6–15). He had dedicated the temple, and his building projects were fast becoming world renowned (chaps. 6–8). Little did Solomon realize, even with all his wisdom, that he was in danger of making foolish, disastrous decisions. Yet, God would take the initiative to alert Solomon to dangers ahead.

9:1–5. After Solomon had finished building the temple, God appeared a second time, as He had appeared to him at Gibeon (vv. 1–2; cf. 3:4–15). God assured Solomon that He had heard his prayer at the temple dedication. God’s statement, My eyes and My heart will be there perpetually (v. 3) refers to His constant presence with His people in the temple. Even though the highest heavens could not contain the living God, He would show His covenant love to His people by residing in a unique way in the temple. However, God’s promise was tempered by two conditional warnings. The first warning was stated positively. God promised Solomon that if he would walk … in integrity of heart and uprightness, then God would establish his throne and he would not lack a man on the throne of Israel (vv. 4–5).

9:6–9. The second warning was stated negatively. If Solomon or his sons were to turn away from following God they would be cut off from the land and the house (i.e., the temple, v. 7). All would be lost if idolatry replaced the worship of God in the temple. After all, the behavior of the king was the example that the people were to follow (Dt 17:18–20), and that example was to be upright in every way. If the nation followed after other gods, Israel would become a proverb and a byword among all peoples (v. 7). That is, Israel would become the proverbial example of what life would be like when the Lord is abandoned. These exact predictions were fulfilled when Jerusalem fell to Babylon (cf. Jr 52).

5. Solomon’s Splendid Kingdom (1Kg 9:10–10:29)

After the account of Solomon’s second encounter with the Lord, there follows a rather lengthy description of what Solomon completed at the end of twenty years of his reign. This is the midpoint of Solomon’s 40-year reign from 970–930 BC. Although his kingdom looked glorious, there were early indications of disaster ahead due to Solomon’s attraction to foreign women and their idolatry.

9:10–14. After a long trade relationship with Hiram, king of Tyre, who had supplied the cedar and cypress timber and gold for Solomon’s building projects (v. 11; cf. 5:1–12), instead of paying Hiram with cash and provisions Solomon gave Hiram twenty cities in the land of Galilee, the area of northwest Israel not far from Tyre (v. 12). However, these cities did not please Hiram, so he called them Cabul, a Hebrew word meaning "as good as nothing" (v. 13). Although the cities were worthless to Hiram, he supplied Solomon with 120 talents of gold (v. 14). Solomon was the dominant monarch in the relationship, and his heart was revealed back in v. 11 in the statement that Hiram gave Solomon wood and gold according to all his [Solomon’s] desire. Material desires were starting to influence Solomon’s actions.

9:15–19. This section (vv. 15–24) provides clarification about the forced labor Solomon used in his building projects (cf. 5:13). These workers built the house of the Lord, as well as Solomon’s own house. His other projects included Millo, probably Solomon’s fortifications of Jerusalem, as well as his three chariot cities of Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer (v. 15). These archaeological sites have been identified by their extensive stable areas and matching Solomonic gates. Some of the motivation for building may have come from Solomon’s father-in-law, Pharaoh king of Egypt who captured Gezer (about 20 miles west of Jerusalem), and then gave it as a dowry to his daughter (v. 16). So Solomon rebuilt Gezer (v. 17) indicates that the gift led to Solomon’s rebuilding of the city, perhaps a subtle pressure placed on Solomon by his wife or father-in-law. His other building projects include cities for his chariots … and all that it pleased Solomon to build … in all the land under his rule, indicating the self-focus of his projects.

9:20–24. The laborers who carried out these various building projects were the people who were left of the Amorities, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Hivites and the Jebusites after the conquest under Joshua (cf. Dt 7:1–2). He used manpower not of the sons of Israel (v. 22) because Solomon did not turn his own people into slaves. His building projects, although impressive, did not endear him to his subjects (cf. 12:4).

9:25. In obedience to the law, three times a year, at the three annual pilgrim festivals (the Feast of Unleavened Bread, the Feast of Weeks, and the Feast of Booths; cf. Ex 23:14–17; Lv 23:34–43) Solomon offered burnt offerings and peace offerings on the altar. Because he was not a priest, he did not personally make these offerings, but the priests made them on his behalf, as they did for everyone who brought his or her offering to the temple.

9:26–28. Hiram not only supplied lumber for Solomon’s buildings, he also supplied gold (9:14). Tyre was a sea merchant empire (cf. Is 23:1–8), so when Solomon needed sea power, he asked Hiram to send his sailors to man the ships. Solomon built a fleet of ships on Israel’s Red Sea port of Ezion-geber, which is near Eloth (Israeli’s modern port city of Eilat). In partnership with Hiram, ships were sent to Ophir (v. 28; the actual location is unknown, but the Arabian coast, the African coast, or India have all been suggested) to acquire four hundred and twenty talents of gold, about 16 tons. God had said He would give Solomon riches (cf. 3:13), but there was the serious danger of violating the precautions placed on Israel’s king in Dt 17:17b.

10:1–5. Solomon’s fame spread across the nations, and people wanted to have an audience with him. One such person was the queen of Sheba. Sheba was located in southwest Arabia in modern-day Yemen, about 1,200 miles from Jerusalem (not Ethiopia, as commonly suggested). Her arrival in Jerusalem was prompted by what she heard about Solomon’s fame in connection with the name of the Lord (v. 1). She wanted to test him with difficult questions, meaning that she tested him with riddles. The Hebrew word translated difficult questions refers to a type of dialogue carried out by heads of state in the ancient world. In the course of her visit, the queen of Sheba asked questions and observed all that he had done. What she saw so moved her that there was no more spirit in her (v. 5), that is, she was overwhelmed with the splendor of Solomon’s kingdom.

10:6–9. The queen of Sheba admitted that what she was told of the king was a true report, although she did not believe the reports until she heard of Solomon’s wisdom firsthand. This led her not only to praise Solomon but also to proclaim the greatness of God. She said, Blessed be the Lord your God who delighted in you … and made you king, to do justice and righteousness (v. 9). Solomon was given a subtle reminder through this wise woman’s words that what he had accomplished was the Lord’s doing.

10:10–13. Sheba ended her visit by giving to Solomon gifts before returning home: Never again did such abundance of spices come in as that which the queen of Sheba gave King Solomon. Solomon joined again in partnership with Hiram to bring gold from Ophir; Solomon was accumulating gold from a variety of sources (vv. 10, 11, 14; cf. 9:11). And yet God had warned all the kings of Israel to avoid what appeared to be the ever-increasing power of self-indulgence (cf. Dt 17:17)

10:14–25. Solomon’s accumulation of gold is a key idea, mentioned 11 times in this section (vv. 14, 16–18, 21–22, 25). In one year alone Solomon received 666 talents of gold, about 25 tons (v. 14). But in addition, Solomon was receiving tax revenues from traders … merchants and all the kings of the Arabs and the governors of the country (v. 15). Solomon put his accumulating wealth to impressive use in making shields (vv. 16–17), his great throne (vv. 18–20), and even drinking vessels (v. 21) out of gold. In comparison to the gold in his kingdom, silver was not considered valuable in the days of Solomon (v. 21). Those who were around Solomon in Jerusalem were impressed with his buildings, his gold and silver, ivory and apes and peacocks (v. 22). Not only had he been blessed with great wisdom, but also King Solomon became greater than all the kings of the earth in riches and in wisdom (v. 23). Yet no one except God, the true King, would see how all these material things were influencing Solomon’s heart. Apparently, large amounts of wealth also came from those monarchs like the queen of Sheba when they had an audience with Israel’s king (vv. 24–25).

10:26–29. The final section of chap. 10 summarized the high point of Solomon’s reign. What God had promised Solomon (chaps. 3–5) had surely come to pass. However, Solomon appeared to be motivated perhaps more by material accumulation than by spiritual allegiance. Solomon imported horses … from Egypt and Kue, probably Cilicia in modern Turkey (v. 28). The king who was to meditate on God’s law daily (cf. Dt 17:18–19) was living contrary to this same law by sending merchants back to Egypt, a place where the Lord told them to "never go back that way again" (Dt 17:16). Instead of growing closer to the Lord spiritually, Solomon’s heart was headed in a different direction, propelled by luxury and fame.

C. Solomon’s Divided Heart and Spiritual Decline (1Kg 11:1–43)

After an initial impressive reign, Solomon’s monarchy came to a tragic end because he turned to the worship of idols. God had used him to build the temple and unite the people. People everywhere came to Israel’s king to interact with his wisdom and to observe the great building projects he undertook. But in spite of great accomplishments, Israel’s glory would never again be the same, for at the end of his reign Solomon’s kingdom would be divided. Solomon’s choices, both good and bad (but especially bad), would be repeated by his offspring. The people in exile, for whom 1 and 2 Kings were written, would read of Solomon’s exploits and grieve over the consequences of his sin. But the ultimate aim of this record would be for the readers in exile to ponder the severe consequences of sin, to return to the Lord consistent with Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the temple (cf. 8:46–53), and to keep looking forward to the promised messianic King.

11:1–5. Solomon’s downfall politically and spiritually was the result of his heart being turned away for the Lord because of his love for many foreign women along with the daughter of Pharaoh. He took these wives from the nations concerning which the Lord had clearly said, You shall not associate with them … for they will surely turn your heart away after their gods (v. 2; cf. Dt 7:3–4; 17:17). The magnitude of his spiritual betrayal was evident in the multitude of women whom Solomon married or had in his harem—seven hundred wives, princesses, and three hundred concubines (v. 3). A concubine was a female companion or slave with whom her master had rights to sexual relations, but who was not a legal wife; whereas a queen was a wife legally married to the king, and her children were legitimate heirs. Although the Lord created marriage to be between one man and one woman (cf. Gn 1:27; 5:2; Mk 10:5–9), by the patriarchal period it was not unusual for men to have more than one wife, often with disastrous consequences. However, in Solomon’s case his multiple wives/concubines were unheard of in magnitude, and the disastrous results were likewise monumental. The severity of the problem was also amplified with the acknowledgement that Solomon held fast to these pagan women in love, and his wives turned his heart away after other gods (vv. 3–4).

11:6–13. The king’s love for foreign women caused him to take even more heinous action. He built high places for Chemosh the detestable idol of Moab and for Molech the detestable idol of the sons of Ammon (v. 7; cf. Lv 18:21). These religions demanded vile worship practices including child sacrifice to these gods. Solomon made provision for all his foreign wives, who burned incense and sacrificed to their gods (v. 8). At the same time, God was true to His Word regarding punishment for idolatry (cf. 9:6–9). The Lord was angry with Solomon because his heart was turned away from the Lord (v. 9). The judgment for his sin was Solomon’s loss of the kingdom, as the Lord said, I will surely tear the kingdom from you, and will give it to your servant (v. 11). The only comfort Solomon had was that God would not do it in his lifetime, but in the lifetime of his son (v. 12). The unexpected reprieve was for the sake of My servant David because of David’s loyalty to God, and for the sake of Jerusalem, the city God had chosen as the place where His name would be exalted (v. 13; cf. 9:3; 2Sm 7:13; 2Kg 19:34; 21:4–8; Ps 132).

This entire section is the narrative proof that Solomon, despite building the first temple, did not fulfill the messianic promise of 2Sm 7:12–16. Hence, Israel was to keep looking for the Son of David who would obey the law perfectly and fulfill the promises made to David (cf. 2Sm 7:12–16, see discussion at 1Kg 6:11–13).

11:14–22. The Lord raised up three enemies as adversaries against Solomon. First, Hadad the Edomite was from the royal line in Edom. His bitterness toward the house of David originated when Joab, David’s military commander, had gone to Edom to bury the slain (2Sm 8:13–18). Joab apparently went beyond his assignment and struck down every male in Edom (vv. 14–16). Hadad fled to Egypt with certain Edomites (v. 17) as well as men from Paran. While in Egypt, Hadad gained the favor of Pharaoh, who gave him a house … land … and a wife (vv. 18–19). He also had a son, Genubath (v. 20), whose name means "to steal," which may reflect Hadad’s thinking that the household of David had stolen the lives and lands of people he loved. However, on learning of both David’s and Joab’s deaths, Hadad sought permission from the pharaoh to return to his own country (vv. 21–22). He was only one of three enemies of Solomon in the remaining years of his reign.

11:23–28. The second adversary God raised up was Rezon, who had fled from his lord Hadadezer king of Zobah, a city-state south of Damascus (v. 23; cf. 2Sm 8:3–6; 10:8) Apparently sometime after his escape from Hadadezer, Rezon organized a marauding band that became a thorn in Solomon’s side all the days of Solomon (vv. 23–25). This was in the second half of Solomon’s monarchy, since there was "safety" in the land during the earlier part of his reign, while he was building the temple (1Kg 4:25). Instead of being adored by visiting heads of state, now Solomon was confronted with the likes of Rezon, who abhorred Israel (v. 25) and her king from his kingdom in Aram (in modern-day Syria).