THE BOOK OF BARUCH

INTRODUCTION, COMMENTARY, AND REFLECTIONS

by

ANTHONY J. SALDARINI

Introduction

The book of Baruch is a five-chapter pseudepigraphic work attributed to Baruch, the highly placed Jerusalem scribe who appears in the book of Jeremiah (chaps. 32; 36; 43; 45). It is often called 1 Baruch to distinguish it from 2 and 3 Baruch, apocalyptic narratives from the late first and second centuries ce and from 4 Baruch, or Paraleipomena of Jeremiah, a narrative about the destruction of the Temple in 586 bce. Baruch is part of a cluster of writings associated with the prophet Jeremiah and the destruction of the Temple in 586 bce. It is extant in Greek, though parts or all of it were translated from a Hebrew original. In the Septuagint it immediately follows the book of Jeremiah and precedes Lamentations; in the Vulgate it follows Lamentations and includes the Letter of Jeremiah as a sixth chapter. Baruch is recognized as canonical by Roman Catholics and the Orthodox communities. It is not recognized as canonical by the Jewish and Protestant communities, but is classified with the apocrypha.

Many commentators have described Baruch as a very derivative, composite work, lacking in originality and unity, and "substandard" in comparison with the Hebrew Bible. Carey Moore, for example, explains that the Christian church bypassed Baruch because "the book’s literary style, which at best is uneven in quality, was not sufficiently strong or memorable to compensate for the book’s theological and religious weaknesses, especially in the book’s lack of originality and consistency." Such comments imply that Baruch and other Second Temple Jewish literature reflect a time of decline. They fail to appreciate the vitality and creativity of Second Temple Jewish literature, of which Baruch is an example. Like all prayers and poems of that era, Baruch uses biblical words, phrases, themes, and ideas. But Baruch and Second Temple literature are notable for their innovative uses of biblical traditions to meet new circumstances and to express intense community distress and aspirations.

STRUCTURE, UNITY, AND GENRES

Baruch may be divided into four uneven parts, the first two of which are prose and the second two, poetry: (1) narrative introduction (1:1–14); (2) prayer of confession and repentance (1:15–3:8); (3) wisdom poem of admonition and exhortation (3:9–4:4); (4) poem of consolation and encouragement (4:5–5:9). Their distinctive styles, themes, and language have led commentators to postulate multiple authors or to deny to the book any coherence or substantial unity. Although the parts of Baruch are based on biblical and Second Temple models and may have been written independently before being incorporated into the final work, the final author has linked the parts with words, themes, and traditions so that they work together to form a rhetorical and literary unity. Such composite works, which underwent extensive editing, are common in Second Temple literature (see, e.g., 1 Enoch; Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs) as well as in the Bible (see, e.g., Daniel and especially the versions of the book of Jeremiah to which Baruch is related). In Baruch the final author has melded the parts into a dramatic whole. After he sets the scene in the introduction, he moves from suffering and repentance for sin (1:15–3:8) to devotion, to wisdom and obedience, and to God’s commands (3:9–4:4); he concludes with encouragement to persevere in suffering and with the promise of divine intervention (4:5–5:9).

LANGUAGES

Baruch is extant in a Greek version that was probably translated from a Hebrew original. Translations of Baruch into Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, Armenian, and Arabic have also survived. The Syriac version is especially helpful in interpreting the Greek. The majority of scholars agree that the Greek of the prayer of confession and repentance, along with the introduction (1:1–3:8), was translated from Hebrew. The Greek contains Hebraisms (e.g., 2:26, literally in Greek, "where your name has been called over it") and translation errors (e.g., 1:9, where the Greek translator chose the wrong meaning for the Hebrew

מסגר [masgēr], which can refer either to "prisoners" or to "smiths"; see the Commentary on 1:8–9). In general, a comparison of the Greek version of Jeremiah with Baruch 1:15–3:8 indicates that the same person translated both Jeremiah and Baruch from Hebrew. Whether the wisdom poem and the poem of consolation and encouragement derive from Hebrew originals is still debated, though a successful retroversion of these poems into Hebrew with extensive commentary by David Burke has tipped the balance toward a Hebrew original.DATES AND PROVENANCE

Since Baruch contains four distinct sections, many scholars assign separate dates to them and another to the final form of the book. Modern commentators generally place the final form somewhere in the Greco-Roman period, from 300 bce to 135 ce, not in the Babylonian period assigned it by the narrative frame. Beyond that there is little consensus. All acknowledge that the book contains only the vaguest allusions to events contemporary with the author(s) and that since the book is couched in traditional language, it has a "timeless" quality. Arguments for the dates of the book and its parts depend upon the Greek translation of the book, literary relationships with other works, and the tone and atmosphere of the whole book.

1. The Greek Translation of Bar 1:1–3:8. As noted in the section on language, the prayer of confession and repentance was translated from Hebrew into Greek by the same person who translated Jeremiah. Since the grandson of Ben Sira, who translated the Wisdom of Ben Sira (Ecclesiasticus) into Greek in Egypt by 116 bce, refers to the Law and the Prophets as a well-known and accepted collection in the Greek-speaking community of Alexandria, the Greek version of Bar 1:1–3:8 must have been completed before 116 bce.

2. Literary Relationships. The prayer of confession and repentance (Bar 1:15–2:18) has a detailed literary relationship with the Hebrew prayer of repentance in Dan 9:4–19 (see Commentary on 1:15–3:8 for specifics). Many have interpreted Bar 1:15–2:8 as dependent on Daniel 9 and thus later than 165 bce. However the type of dependency and the dates of both works are uncertain. Even though the prayer in Baruch is much more expansive that that in Daniel, both may have independently adapted an earlier prayer that is now lost. Even if Baruch depends on Daniel 9, the prayer in Daniel 9 is probably an earlier work incorporated into the apocalyptic visions of Daniel 7–12.

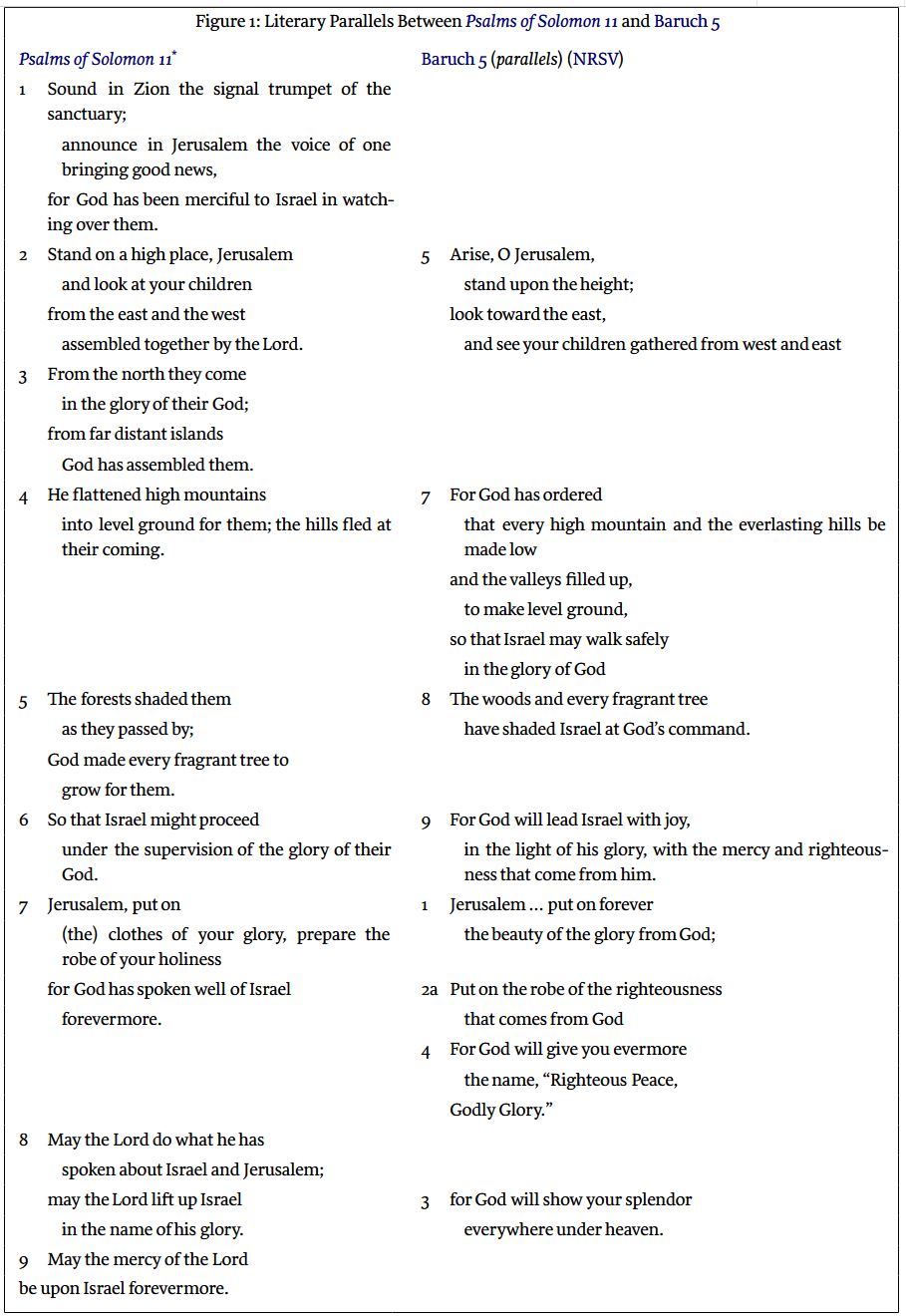

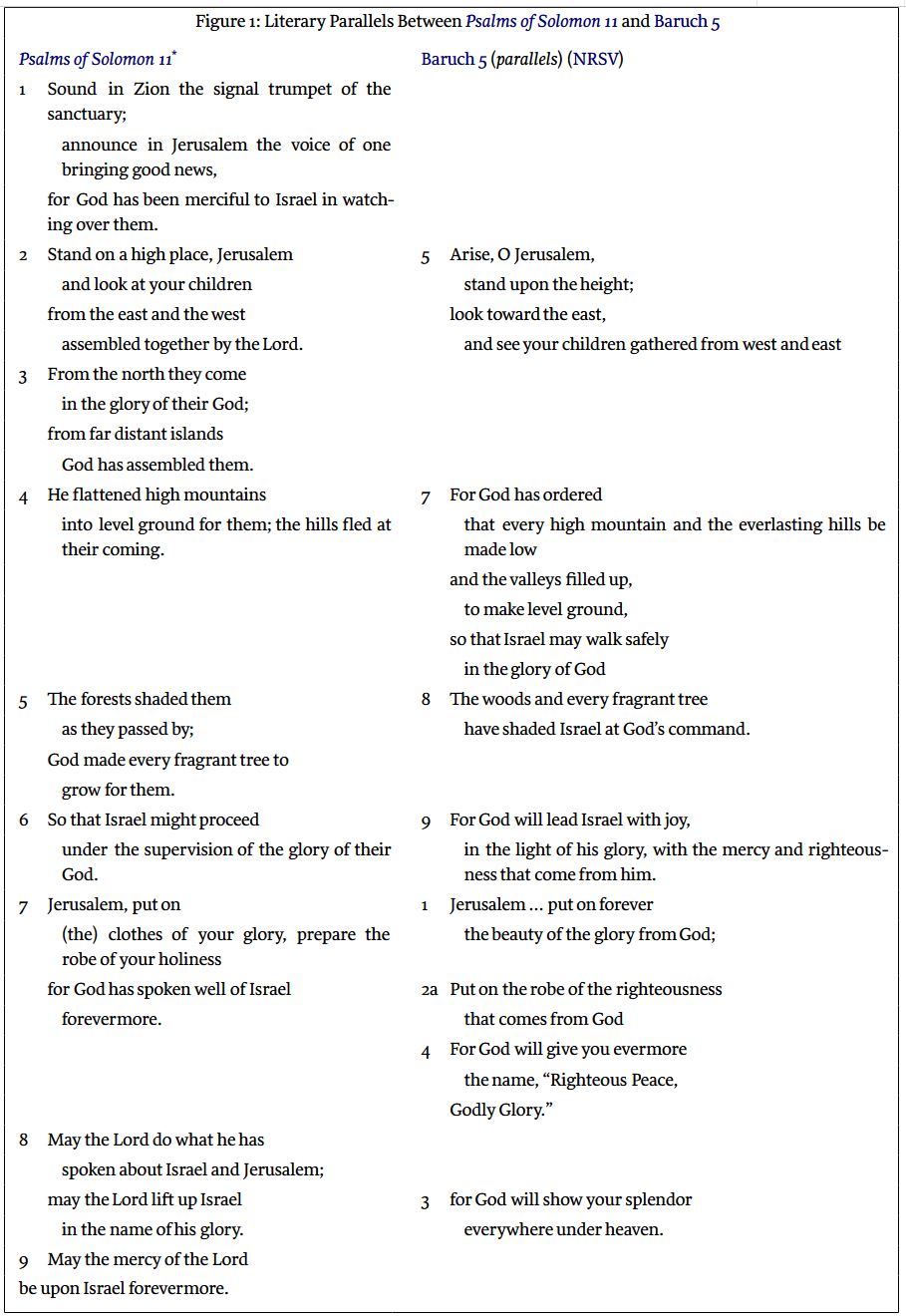

The poem of consolation and encouragement (Bar 4:5–5:9) contains a passage (Bar 5:5–9) that has a close literary relationship with Psalms of Solomon 11 (see fig. 1, 972). Commentators have frequently used this relationship to date either the poem of consolation and encouragement or the whole of the book of Baruch, but uncertainties about the literary relationship and the date of Psalms of Solomon 11 undermine the arguments for the date of Baruch. Many commentators have argued that the author of Baruch used Psalms of Solomon 11 because they see Baruch as more tightly organized and literarily unified. But other commentators have argued that Psalms of Solomon is dependent on Baruch. On the other hand, the poem is so traditional in language and thought that both Psalms of Solomon 11 and Baruch 5 could be independent variations on a common source.

Thus arguments that the whole of Baruch or at least the last section is based on the date of the Psalms of Solomon (after the Roman conquest in 63 bce, since these psalms allude to Pompey, the Roman general) rest on shaky ground. In addition, some commentators think that Psalms of Solomon 11 may have been an earlier poem incorporated into the collection. If so, then the author of Baruch would have had access to this psalm before 63 bce.

In summary, a hypothesis of a common source for the Psalms of Solomon 11 and Bar 5:5–9 is more consonant with the shared themes, forms, and expressions found in Second Temple Jewish prayers. The author of Baruch draws upon widespread and deeply felt hopes for the vindication and reconstitution of Israel as a nation under God’s protection. Baruch’s literary relationships with Daniel 9 and Psalms of Solomon 11 locate Baruch solidly within the Second Temple period but do not support a more precise date. Similarly, the thought and wording throughout Baruch depend on the biblical Law and Prophets, especially Deuteronomy, Jeremiah, and Isaiah 40–66. Thus Baruch is probably from the Hellenistic period (late 4th cent. bce on), when the OT canon began to take shape and became communally recognized.

3. Internal Evidence. The internal atmosphere of the book and allusions to its time of composition are vague and sometimes contradictory. The introduction (1:1–14), which assumes goodwill toward the reigning monarchs for whom it requests prayers, contrasts to the final prayer of consolation and encouragement, which manifests intense anger against the oppressive nations (see 4:31–35). The chronology of the introduction understands the deportation as a recent event (1:11–12), but the wisdom poem alludes to an exile of long duration (2:4–5; 3:10–11; 4:2–3). In the introduction either the Temple is standing (1:10) or sacrifices are being offered at the Temple site in Jerusalem, but in the prayer of repentance the Temple has been destroyed (2:26). As noted previously the content of the prayers resembles that of Second Temple literature in general and does not help with dating.

4. Conclusion. The Greek period (332–63 bce) is the most probable setting for most of the materials in Baruch, and within that period the second century has found most favor with commentators. The lack of a detailed polemic and crisis atmosphere leads Moore to place Baruch early in the second century bce, before the Maccabean war with Antiochus IV (167–164 bce) and the conflicts with his successors. Others, such as Goldstein (followed by Steck), put it after the Maccabean war.11 Other scholars differ and put Baruch in the Roman-Herodian period (63 bce–70 ce) with its simultaneous accommodation to Roman rule and fierce resentment of oppression. Others associate the hope of restoration in Baruch with the aftermath of the destruction of the Temple by the Romans in 70 ce. In the end, no firm and widely persuasive conclusion has been reached because the urgent prayers of Israel, the lamentation over the sufferings of exile, and the hopes for the restoration of Israel and Jerusalem are common themes in Jewish literature from the sixth century bce to the second century ce and have a protean quality that allows them to be applied to various situations.

PLACE, AUTHORSHIP, AUDIENCE, AND PURPOSE

Baruch as a whole is oriented toward Jerusalem. The author addresses a personified Jerusalem and her inhabitants; and Jerusalem addresses the exiles, her former inhabitants. The prayers and exhortations seek the restoration of Jerusalem and her inhabitants. Exile is a temporary state, to be ended by God’s intervention. Thus Baruch probably originated in Jerusalem. The author knew thoroughly the biblical and Second Temple traditions and supported worship at the Temple, the holiness of Jerusalem, the restoration of Israel, and obedience to the Torah. Baruch, the pseudonymous author chosen for the book, was a highly placed Jerusalem scribe in the time of Jeremiah. The author may also have been a teacher or an official in Jerusalem, part of a learned circle devoted to the study and promotion of the traditions of Israel. In the swirl of Hellenistic conflicts and threats to safety, the author sought to influence the outlooks, commitments, and policies of the Jerusalem leadership and people. Political, social, cultural, and religious groups were numerous and varied during this period. The book of Baruch encouraged all to adhere to the traditional deuteronomic theology, the wisdom of Israel articulated in the Torah, the commandments as a guide for life, and the post-exilic prophetic hopes for restoration of Jerusalem and Israel. It sought to clarify and establish the political, social, and religious traditions of Israel in Jewish society and to guide Jews in their responses to oppressive imperial rule and attractive foreign culture.

THOUGHT AND THEOLOGY

Baruch draws upon the traditions of Israel as they developed from the Babylonian exile (586 bce) through the Second Temple period. Each of the parts of Baruch has been influenced by different biblical books and traditions—for example, but not exclusively, 1:15–3:8 by Daniel 9, Jeremiah, and Deuteronomy; 3:9–4:4 by Job 28 and the wisdom tradition, and 4:5–5:9 by Isaiah 40–66. The theological emphases of each section correspond to their literary genres and purposes. The confession and prayer of repentance addresses God with the liturgically proper title "Lord" and petitions for forgiveness. The wisdom poem addresses God with the most general and universal Greek word for "God",

Θεός (theos), in the manner of international wisdom. Despite that, the author identifies true wisdom with the biblical law (Torah) and wise behavior with obedience to God’s commandments, as do other second-century writings, such as Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) 24. The poem of consolation and encouragement promises the eventual restoration of Israel and Jerusalem and the overcoming of the nations who dominate and oppress them. Here God is frequently designated as eternal or everlasting, as befits God’s comprehensive, long-term restorative role.The particularities of Baruch can best be seen against the background of the outlooks, political stances, and religious programs of other Jewish literature and groups in the Second Temple period. Contrary to many sectarian polemical texts, such as those found at Qumran, Baruch does not distinguish between those Jews who are faithful to a certain way of keeping the law and those who are unfaithful. The author of Baruch invites all Jews to acknowledge the nation’s sinfulness, to repent, to obey the commandments, and to hope for divine assistance. He desires the reunification of all exiles with the Judeans in the land, and his norms for correct attitudes and behavior are drawn from the mainstream biblical traditions without emphasis on special practices or beliefs. The arguments over laws and calendar found in the book of Jubilees, the Damascus Document, and other works are entirely absent.

Baruch does not promote any of the new beliefs and world views that appeared in apocalyptic literature. Like the Hebrew Bible (except for Daniel 12), Baruch does not look forward to life after death but expects divine intervention and restoration of Israel in this world. The nations, which have persecuted Israel, will be punished and subjugated; but no messiah will come to defeat them or lead Israel, nor is any universal judgment or wholesale destruction envisioned. Rather, the desired result of the restoration is for Israel to dwell in its land in peace. Special revelations and cosmic battles between good and evil, such as those found in Daniel, do not appear here.

The author of Baruch has produced a middle-of-the-road, traditional theology to which Israel can adhere under all circumstances. Baruch’s very generality and lack of originality, for which it has often been criticized, made it attractive and available to Jews of every inclination. The book seems to have been especially useful to Jews in the Greek-speaking diaspora, since it survived in Greek.

Baruch has not been greatly or directly influential on Christian literature. It shares with Christianity a stress on confession and repentance for sin, but both derived it from the Hebrew Bible. The sin of sacrificing to demons rather than to God appears in 1 Cor 10:20 and Bar 4:7, but both may be dependent on Deut 32:17. Both Baruch and Paul attack Greco-Roman wisdom as false (Bar 3:16–28; 1 Cor 1:18–25), but no direct literary relationship can be established.

The wisdom poem in Baruch may have had a literary influence on Paul’s Letter to the Romans and the Gospel of John. Paul’s argument that one does not need to ascend to heaven or descend into the abyss to find righteousness (Rom 10:6–8) is based on Deut 30:12–14, a text that has also influenced Bar 3:29–30. Baruch stresses both the impossibility of humans’ finding wisdom on their own and the presence of wisdom among humans as a divine gift (Bar 3:36–4:1). This interpretation and elaboration of Deuteronomy accords closely with Paul’s analysis of the divine gift of righteousness brought by Jesus.

Baruch 3:29–4:4 also speaks of wisdom in a way parallel to the Gospel of John’s discourse about Jesus the son of God in John 3:13–21 and 31–36. In both Baruch and John humans cannot ascend to heaven to get wisdom, but rather wisdom in Baruch and the son of the Father in John descend from heaven to humans as a divine gift. In Baruch, wisdom is associated with life, light, and salvation, as is Jesus in John. Wisdom understood as the law dwells with Israel in Baruch just as Jesus dwells with humans as the truth, the word, and the way in John. In Deuteronomy 30, Baruch, and John, God’s presence on earth (commandments, wisdom, Jesus) is available to all who will accept it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Commentaries:

Fitzgerald, Aloysius. "Baruch." New Jerome Biblical Commentary. Edited by Raymond Brown et al. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1990. A short introductory commentary providing the non-specialist reader with commentary on historical background; meanings of various words, phrases, and sentences; and basic theological interpretation.

Harrington, Daniel J. "Baruch." In Harper’s Bible Commentary. Edited by James L. Mays. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988. An introductory commentary with particular focus on the meaning of the text.

Moore, Carey A. Daniel, Esther, and Jeremiah: The Additions. AB 44. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1977. Provides a general introduction and moderately detailed textual notes. Sparing in interpretation. Advances the thesis that Baruch consists of five separate compositions loosely edited into one work.

Steck, Odil Hannes.

Whitehouse, O. C. "1 Baruch." In The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament. Volume 1. Edited by R. H. Charles. Oxford: Clarendon, 1913. Though in many ways now substantially outdated, this volume offers a highly detailed and still relevant discussion of Baruch’s textual history, language, authorship, and similar issues. Detailed textual notes accompany the author’s translation, which is similar to the KJV in style.

Specialized Studies:

Nickelsburg, George W. E. "The Bible Rewritten and Expanded." In Jewish Writings of the Second Temple Period. Edited by Michael E. Stone. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984. A general discussion of Baruch in light of the state of scholarly knowledge and discussion in the early nineteen eighties. Analyzes Baruch’s compositional history and relationship to other texts including the books of Jeremiah and Daniel.

———. Jewish Literature Between the Bible and the Mishnah. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1981. A short discussion and summary of Baruch, which is treated as a unified composition.

Schürer, Emil, Geza Vermes, Fergus Millar, and Martin Goodman. The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 b.c.–a.d. 135). Volume 3.2. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1987. An update of a (seriously flawed) classic early twentieth century German work. Provides a general introduction and summary of Baruch, a concise but strong discussion of composition history, Baruch’s place in the canon, and its use by the early church and patristic writers. Good bibliography up through the early nineteen eighties.

Outline of Baruch

I. Baruch 1:1–14, Narrative Introduction

A. 1:1–9, Narrative Introduction

B. 1:10–14, The Cover Letter

II. Baruch 1:15–3:8, Prayer of Confession and Repentance

A. 1:15–2:10, Confession of the Judean Community

B. 2:11–3:8, Prayer of Repentance for Mercy and Deliverance

III. Baruch 3:9–4:4, Wisdom Admonition and Exhortation

A. 3:9–14, Rebuke and Call to Israel

B. 3:15–31, Wisdom Hidden from Humans

C. 3:32–4:1, God Gives Wisdom to Israel

D. 4:2–4, Final Exhortation to Accept Wisdom

IV. Baruch 4:5–5:9, A Poem of Consolation and Encouragement

A. 4:5–9a, Introductory Poem of Consolation

B. 4:9b–16, Jerusalem’s Lament to Neighboring Peoples

C. 4:17–29, Jerusalem’s Exhortation to Her Children

D. 4:30–5:9, Poem of Consolation to Jerusalem

BARUCH 1:1–14

Narrative Introduction

Overview

The narrative introduction to Baruch sets the scene for the prayers and exhortations that follow in the rest of the book (1:15–5:9). However, the introduction is notorious for its conflicts with the body of the book and for historical errors. These conflicts undercut the narrative coherence of the book as a whole and raise questions concerning the purposes of the author of Baruch. (Theories about the actual historical setting, author, and date of Baruch are treated in the Introduction.) For example, in the introduction (1:6–7, 10), the Babylonian exiles send money for the priests in Jerusalem to offer sacrifices; but the prayer of confession and repentance (1:15–3:8) alludes to the destruction of the Temple (2:26), and the lament in the final section implies that Zion has been devastated (4:9–35). The introduction requests that prayers be offered for the Babylonian king and his son so that the exiles may live under their protection (1:11–12). By contrast, the prayer of confession and repentance stresses the shame and suffering of exile (2:4, 13; 3:8), and the poem of consolation and encouragement (4:5–5:9) attacks the savagery of the nations and promises punishment for them (4:14–16, 25, 31–35). The introduction treats the exile as an event that began five years previously (1:2), while the wisdom poem treats it as having been lengthy (3:10–11; 4:2–3). In identifying Belshazzar as the son of Nebuchadnezzar (1:11–12), the introduction repeats an error found in Dan 5:2. Actually, Nabonidus was the father of Behshazzar, and they were coregents when defeated by Cyrus the Persian in 539 bce. Finally, the narrative framework of Baruch fits uneasily into some biblical narratives. Baruch is placed in Babylon, contrary to Jer 43:1–6, which recounts his forced flight with Jeremiah into Egypt.

The introduction’s mention of money sent for sacrifices in the Temple assumes the period between the first and second deportations of Jerusalemites to Babylon (597–586 bce) while the Temple was still standing (1:11–12). The allusion to the Temple’s destruction in 2:26 supports a narrative setting between the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple and the return of some exiles under Cyrus the Persian (586–538). The dates of events cited or alluded to in the introduction are muddled. The month in 1:2 is unnamed in the text, though it is usually taken to be the fifth month, Ab, which is the month in which Jerusalem was destroyed. The next date is Siwan, the third month (1:8), which puts the arrival of the collection ten months later than it was gathered in Babylon. The final "date" is the "the day of the festival and the days of the [sacred] season" (1:14), which is usually taken as a reference to the feast of Tabernacles in the seventh month, Tishri.

Each of these problems will be taken up in the commentary. Here two general comments and two conflicting hypotheses concerning the narrative chronology will provide orientation to the world of the text and to the purposes of the author(s) in creating this narrative world. The author of Baruch works with a variety of traditions found in other literature from the Second Temple period, sometimes interpreting scriptural verses in a surprising way and sometimes drawing upon alternative narratives and scenarios that were common stock in his time. He does not seek historical accuracy in the modern sense, nor does he have earlier, reliable historical sources. Furthermore, granted the complex literary and social context of Second Temple Judaism, no theory can fully explain all the narrative elements, much less discover what happened historically at the time in which the narrative is set. The goal must be to understand the book through understanding the narrative world envisioned by the author.

The chronological setting of Baruch can be understood as 597–586 bce, between the first and second deportations, or as 586–538 bce, between the destruction of the Temple and the return of some of the exiles. The case for 597–586 is based mainly on the request that sacrifices be offered in Jerusalem (1:10–11). The "fifth year" in 1:1 is the fifth year of King Jeconiah (593/592 bce), who replaced his father during the first siege of Jerusalem in 598/597. The initial visions of the book of Ezekiel are dated to that same year (Ezek 1:2). According to this chronology, the exiles send offerings to the Temple, which is still standing. This situation corresponds to that of the actual audience of Baruch during the Second Temple period, when the Temple was once again standing. Many Jews lived in the diaspora and sent offerings to the Temple in Jerusalem. This hypothesis solves some problems but leaves others outstanding. The setting between the deportations does not correspond to the allusions to a long exile in later sections (a new generation in 3:4; endurance in 4:5, 21, 27, 30). The return of the Temple vessels (1:8–9) is unnecessary, since worship has presumably been carried on from 597 to 592 bce.

The more common chronological setting for the narrative is 586–538 bce, between the destruction of Jerusalem and the return of some exiles under Cyrus. The sense of overwhelming tragedy and loss, the mourning of Zion (4:5–5:9), the promise of return, the deuteronomic theology of punishment for sin all point to the Babylonian exile following the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 586. The major obstacle to this interpretation is the lack of a Temple in Jerusalem to receive the collection for sacrificial offerings and to provide a setting for Joakim and the priests. In this scenario, Baruch envisions the continuation of sacrifice in Jerusalem after the exile of 586. The exiles provide the necessities for the cult, money to buy sacrificial animals, and the holy implements and vessels with which to carry out the rituals (1:6–10). The possibility of sacrifices without the Temple derives from Ezra 3:1–6, where the returned exiles set up an altar and reinstituted sacrifice at the site of the Temple. The author of Baruch merely moves this act forward to provide for greater continuity of worship and for a closer connection of the exiles to Jerusalem all during the exile. In this understanding of events, the expression "house of the Lord" (1:14) would refer to the temple area, not to the building itself, which had been destroyed.

Both hypotheses are far from certain, and neither solves all the problems of the introduction. The latter is more simple and closer to the text. Yet, on a quick reading it appears that the author still seems to presume the existence of the Temple, not just an altar. Perhaps the author left the chronology and setting vague so as to have the richest social and religious context for this teaching. The details of these problems and hypotheses will be addressed in the commentary.

BARUCH 1:1–9, NARRATIVE INTRODUCTION

Commentary

1:1. "The words of the book that Baruch … wrote" refers to the contents of Bar 1:15–5:9. The terms for "book" in Greek are

βιβλίον (biblion) in 1:1, 3, 14 and βίβλος (biblos) in 1:3, translated by the NRSV as "book" in 1:1, 3 and as "scroll" in 1:14. These words come from βύβλος (byblos), meaning "papyrus," and may refer to a strip of papyrus, a papyrus roll, or a document written on papyrus or other material—for example, a letter, a legal document, or a book. In the Greek translation of Jeremiah 29:1 [Greek 36:1], the "words of the biblos" that Jeremiah sent to the exiles in Babylon after the first exile of 597 bce are identified as a "letter" (ἐπιστολή epistolē). In Jeremiah 32:10–16 [Greek 39:10–16] the biblion that Baruch writes is a deed to land, and in Jeremiah 36 [Greek 43] the biblion is a scroll of Jeremiah’s prophecies. The biblion of Baruch is a scroll of prayer, instruction, and exhortation.Baruch, son of Neriah, son of Mahseiah the scribe, is well known from the book of Jeremiah (Jer 32:12), where he records Jeremiah’s teachings (chap. 36) and with his brother Seriah, "chief quartermaster", (

שׂר מנוחה śar mĕnûḥâ) is part of the governing class in Jerusalem for King Zedekiah (Jer 51:59). The three earlier links in his genealogy, Zedekiah, Hasadiah and Hilkiah, are unique to Baruch. The names "Baruch" and "Seriah" have turned up in Judean seal impressions from the seventh–sixth centuries, reading as follows: "Belonging to Berekhyahu son of Neriyahu the scribe" and "Belonging to Seiyahu son of Neriyahu." Baruch was probably an official, as was his brother. Baruch is known for his association with Jeremiah—e.g., transferring land (Jeremiah 32), writing Jeremiah’s prophecies (Jeremiah 36), being consoled by Jeremiah (Jer 45:1–2), being accused of conspiracy and going with Jeremiah to Egypt (Jer 43:3, 6).Although v. 1 says that Baruch wrote this book in Babylon, according to Jer 43:6, he and Jeremiah were taken forcibly to Egypt by the group that assassinated Gedaliah ben Ahikam, the Babylonian appointed governor of Judah. Biographical narratives about Jeremiah were common in post-exilic Jewish literature. Since the book of Jeremiah does not say when or where Baruch and Jeremiah died, they became literarily available for a variety of narrative tasks. For example, in the Dead Sea Scroll 4Q385 (earlier referred to as 4Q385 16 or ApocJerc) Jeremiah accompanies the exiles as far as the Euphrates River, instructing them how to be faithful to God in Babylon. Another fragment of this work places Jeremiah in Egypt, in agreement with the biblical account, instructing the exiles there. The later rabbinic commentary Pesikta Rabbati 26:6 has Jeremiah accompany the exiles as far as the Euphrates to comfort them, a scenario that is consistent with the Qumran Apocryphon of Jeremiah. Presumably such narratives suggested roles for Baruch as well. In 2 Bar 10:1–5, God tells Baruch to instruct Jeremiah to go to Babylon to support the captives while Baruch stays in Jerusalem and receives visions of the future, which he then communicates to the people. In 4 Baruch (Paraleipomena of Jeremiah) 4:6–7 Jeremiah is taken as an exile to Babylon while Baruch mourns in Jerusalem. Sixty-six years later, Jeremiah leads the people back to Jerusalem from Babylon (chap. 8 of 4 Baruch).

Josephus provides a historical context for the movement of Jeremiah and Baruch from Egypt to Babylon, although he does not name them. After retelling the story of Jeremiah and Baruch being taken forcibly to Egypt (Jeremiah 43), Josephus recounts how Nebuchadnezzar conquered Egypt in his twenty-third year, which was the fifth year after the destruction of Jerusalem. Nebuchadnezzar took the Jewish refugees (presumably including Jeremiah and Baruch) from Egypt to Babylon as captives. Analogously, Jer 52:30, a passage found in the Hebrew but not in the Greek (the present Hebrew of Jeremiah is a later version than the Greek), speaks of a third exile in the twenty-third year of Nebuchadnezzar, five years after the destruction of Jerusalem. Later rabbinic interpretations also place Baruch in Babylon. Seder Olam Rabbah 26 tells the story of Nebuchadnezzar conquering Egypt in his twenty-seventh year and explicitly says that he exiled Jeremiah and Baruch to Babylon. Some rabbinic writings radically compress post-exilic chronology so that Baruch was the teacher of Ezra in exile, but then the midrashic author must explain why Baruch and Ezra did not return with the exiles in 538 bce (Baruch was too old, and Ezra stayed behind to care for him).

1:2. The dates given in Baruch do not make obvious and consistent narrative sense. The date at the beginning of this verse lacks the number of the month. The month probably was the fifth month, with the number of the month omitted through the scribal error of haplography, in which the repeated word "fifth" for both the year and the month was dropped. The seventh day of the fifth month is the date of the destruction of the Temple by Nebuchadnezzar’s armies in 586 bce (see 2 Kgs 25:8). Zechariah, in the late sixth century bce, mentions a fast in the fifth month (Zech 7:5; 8:19). Thus the date here would refer to 581 bce, the fifth year after the destruction of the Temple.

Some commentators, however, calculate the fifth year as 592 bce, five years after the deportation of King Jehoiachin and other leaders from Jerusalem to Babylon in 597 (2 Kgs 24:12–16). Ezekiel’s call as a prophet is also placed in the fifth year, on the fifth day of the fifth month (Ezek 1:2). The latter part of v. 2, with its reference to the destruction of Jerusalem, is not decisive in deciding between these two dates. "At the time when" (

ἐν τῶ καιρῶ en tō kairō) may refer to the general period when these events happened, or it may refer to a specific anniversary date (as in 1 Macc 4:54). The presence of a high priest and priests in Jerusalem (v. 7), the request that they offer sacrifice at the altar (v. 10), and the reference to the house of the Lord (v. 14) suggest that the Temple is still standing. On the other hand, the rest of Baruch presumes that the Temple has been destroyed (2:26; for further interpretation of these problems, see the Overview to this section and the Commentary on 1:10–14).1:3–4. The audience for the reading of Baruch’s book is consistent with related biblical materials. Jeconiah, son of Jehoiakim, whose name is found in 1 Chr 3:16–17; Jer 24:1; 27:20; 29:2; and elsewhere, is identical with Jehoiachin in 2 Kgs 24:6–12. He became king in 598 bce during the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, when his father, Jehoiachim, died. He surrendered the city in spring 597 and was taken to Babylon, where he died in exile. With him are "the people" (v. 3), or more inclusively "all the people, great and small" (v. 4). The leaders with Jeconiah are specified as the "sons of the kings"—that is, the members of the royal family ("princes" in the NRSV), the "powerful" (

δυνατοί dynatoi, translated as "nobles" in the NRSV), and the elders. The description of the king and his entourage calls to mind the assembly of the leaders and people to hear the reading of the book found in the Temple during the reign of Josiah (2 Kgs 23:1–2), an assembly that included "all the people great and small." It also recalls the king’s and his court’s hearing (with displeasure) the reading of Jeremiah’s prophecies by Baruch (Jeremiah 36). Finally, the gathering of the king and the people by a river or canal in Babylon replicates the gathering of Ezekiel and the exiles at the River Chebar (Ezek 1:1) and of the group returning with Ezra at the River Ahava (Ezra 8:15).1:5–7. The response of the people (weeping, fasting, and praying) is common in biblical and Second Temple literature (e.g., Neh 1:4; 9:1; Ezra 8:21–23; Dan 6:18; 9:3; Tob 12:8; Jdt 4:13). The collecting of money (lit., silver) for temple offerings according to each one’s means corresponds to the instructions in Deut 16:16–17 on bringing offerings during the pilgrimage festivals. The money is to be sent to the priest Joakim, son of Hilkiah, in Jerusalem (the NRSV has Jehoiakim, the Hebrew equivalent of this Greek name). The Greek has the simple title "priest," but here "priest" refers to the high priest, as it does in the case of Jehoiada, "the priest" in Jerusalem who opposes Athaliah and enthrones Joash (2 Kings 11–12). Joakim’s name is a problem, however. He does not appear in the narrative of 2 Kings as a high priest before the destruction, nor is he on the list of high priests in 1 Chr 6:13–15. According to the biblical narratives, Seriah was the last high priest in the Temple; he was executed after the conquest of Jerusalem (2 Kgs 25:18; Jer 52:24). His son Jehozadak went with the exiles to Babylon (1 Chr 6:15). Thus none of the historical narratives or lists attests to a Joakim serving in Jerusalem immediately after the destruction of the Temple. The name "Joakim," however, is associated with the priesthood. Joakim, son of Jeshua, is high priest in the time of Ezra (Neh 12:10–11), and the fictional book of Judith contains a high priest named Joakim who exercises great power (Jdt 4:6, 8, 14; 15:8). The name is a credible priestly name used for a fictional narrative character. The author of Baruch understands Joakim to be the high priest in Jerusalem from 586 until the return of Jeshua, son of Jozadak (another name for Jehozadak, the high priest who went into exile), under Cyrus the Persian in 538 (Ezra 2:2; 3:2). The author of Baruch probably pictured worship continuing at an altar without a temple before the return from Babylon. The biblical basis for such a scenario is provided by two incidents. After the destruction of the Temple and the murder of the governor Gedaliah, men from Shiloh, Shechem, and Samaria came to Mizpah with grain and incense offerings for the Temple, which was no longer standing (Jer 41:4–7). This brief notice implies that some kind of cultic activity was going on. Similarly and more clearly, the returned exiles set up an altar on the site of the destroyed Temple and offered sacrifices (Ezra 3:1–6).

1:8–9. These two verses do not fit smoothly into the narrative either grammatically or historically, and so some commentators label one or both as glosses. Neither Kings nor Chronicles has a story of King Zedekiah (597–586 bce) making new implements for the Temple after the first deportation. The logic of the story derives partly from 2 Kings, which reports that Nebuchadnezzar cut in pieces and took all the golden temple vessels to Babylon in 597 bce (2 Kgs 24:13). This would leave the Temple without equipment for sacrifice, so the author of Baruch envisions the king making new, less costly silver vessels. However, the biblical account is not consistent within itself or with Baruch. In the final conquest and destruction of Jerusalem in 586, the Babylonians took away both gold and silver implements and vessels (2 Kgs 25:14–15), not just Zedekiah’s silver vessels. In addition, the story of an early return of the temple vessels (v. 8) does not fit smoothly into the narrative. The Greek grammar does not clarify who brought the vessels back to Jerusalem, whether Hilkiah the priest (mentioned in v. 7) or Baruch (mentioned in v. 3). The NRSV and most commentators choose Baruch.26 The letter sent to Jerusalem mentions the money for sacrifices, but not the temple vessels (v. 10). Nevertheless, the logic of the author of Baruch is still clear: Since Zedekiah’s vessels would have been taken to Babylon in 586, the narrative must place their return between 586 and 538, when a group of exiles returned (Ezra 1–3). If Baruch understands that sacrifices were offered during this period, he must ensure that some sacred vessels and implements are returned to Jerusalem along with money to buy sacrificial animals.

The list of groups carried off to Babylon in v. 9 is similar to the lists of those taken to Babylon in Jer 24:1 (officials of Judah, artisans, and smiths) and Jer 29:2 (the queen mother, the court officials, the leaders of Judah and Jerusalem, artisans, and smiths). The NRSV must be corrected in one place and the Greek in another, however. The first group is not "princes," as in the NRSV, but "leaders" or "officials" (

ἄρχοντες archontes, which often translates the Hebrew שׂרים śārîm). The Greek of the second group is "prisoners" (δεσμώται desmōtai), so translated by the NRSV, but this is a translation error from Hebrew. The Hebrew word מסגר (masgēr) has two meanings: "prison" (Isa 24:22) and "smith" (2 Kgs 24:14; Jer 24:1). "Smiths" is clearly the correct choice for a list of exiled productive leaders. Baruch adds to this list of exiles the "people of the land." In Kgs 25:12, by contrast, the poor of the land ("poor of the people") are left to farm the land, and in Jer 24:1 the rich are also listed among the deportees. Baruch, however, consistently stresses the unity and cohesiveness of the people of Israel in exile and in the land. (See Reflections at 1:10–14.)BARUCH 1:10–14, THE COVER LETTER

Commentary

The exiles in Babylon request that a full range of sacrifices, "whole offerings" (

עולה ʿôlâ), "sin offerings" (חטאת ḥaṭṭāʾt), "incense offerings" (לבנה lĕbōnâ), "grain offerings" (מנחה minḥâ), and prayers be offered for the long lives of the Babylonian kings so that they may protect the exiled Judeans. Clearly, the exiles anticipate serving these foreign conquerors and winning their favor. This promoting of a positive relationship with the ruling powers is one common response to conquest in Second Temple Jewish literature that is also found in the prayer of confession and repentance (1:15–3:8), in the stories in Daniel 1–4; 6, and in Esther. It corresponds to Jeremiah’s pro-Babylonian prophecies (Jer 27:6–11) and instructions to the exiles to pray for Babylon (Jer 29:7). Ezekiel promotes the same attitude (Ezek 29:17–20). This school of thought recognized the Babylonian dominance of the Near East and the social and political dissolution of Judea. In its view, a well-intentioned king could be an aid to Judeans in the land and in exile. However, many other works, including the last part of Baruch (4:31–35), express intense resentment toward imperial oppression.The introduction’s link with the traditions in Daniel 1–6 can be seen in the erroneous identification of Nebuchadnezzar as the father of Belshazzar (v. 12), which is also found in Dan 5:2, 11, 18, and 22. In fact, Nabonidus was the father of Belshazzar, and they were the last two Babylonian kings, ruling as co-regents in 539 bce, when Cyrus the Persian conquered Babylon and took over the empire. Nebuchadnezzar was earlier in the sixth century, but he is prominent in Jewish thought because he conquered Jerusalem.

The exiles in Babylon also ask that the Jerusalemites pray on their behalf to God, who is still angry with them (v. 13). They implicitly accept the deuteronomic theology that Jerusalem was destroyed as a punishment for its sins. The rest of the book of Baruch (1:5–5:9) consists of the exiles’ prayers, exhortations, and hopes, which the Jerusalemites are to recite for them in the Temple during the festivals (v. 14). Thus vv. 13–14 are the immediate introduction for the prayer of confession and repentance (1:15–3:8) and for the instruction and exhortation that follow.

The reading of the book or scroll is to take place in the "house of the Lord," which is ordinarily understood as the Temple. Once again, the chronological setting of the narrative in relation to the Temple is unclear (see the Introduction and Overview). If the setting is post-586, as is most probable, then the "house of the Lord" had already been destroyed. "House of the Lord" would then refer to the temple area, where an altar was set up (see the Commentary on 1:7). The NRSV translation of the time of the prayer of confession, "on the days of the festivals and at appointed seasons," is not fully accurate. The Greek is more literally "in the day of the feast [

ἑορτῆς heortēs] and on the days of the festival season [καιροῦ kairou]." This clause may refer to Jewish festivals in general, as in the NRSV, but more likely designates the new year festival in the fall, at the beginning of the seventh month, Tishri, and the eight-day Feast of Tabernacles, beginning on the fifteenth of Tishri.Reflections

The Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem has destroyed the religious world of the exiled Judean community at the beginning of Baruch. Analogously the modern world has destroyed or severely stressed the traditional religious world of many Christians. A normal human reaction in both cases is to walk away sadly. The Babylonian conquerers probably expected the exiled Judeans to assimilate to Mesopotamian culture and cause them no more trouble, just as modern science and secular culture naively expected religion to disappear. However, contrary to expectations, the Judean exiles struggled to maintain their traditional ties and rectify their relationship with God, thus providing a model of fidelity for contemporary believers. Their classic response to disaster—confession of sin, prayer, repentance, instruction, exhortation, and trust in divine mercy and intervention—has been adopted by later Jewish and Christian groups. A return to the core convictions and practices of the religious tradition answers cultural breakdown and fragmentation of communal consciousness. Like the exiled Judean community, contemporary Christians must frankly and robustly admit their feelings and lack of attention to God in order to clarify their vision of God and meet the threats and challenges of a new world.

In Western culture, people view themselves as individuals in a large and often chaotic world. Only the family, or perhaps a small group of friends, stands between the person and an amazing, but often hazardous, universe. The ancient Judeans preserved a resolute sense of community that has been lost in much of the modern world. Although they were separated by hundreds of miles, the Judeans in Babylon and in Judea act as one unified community to confront their national disaster. Although they had suffered and lost their independence, their fellowship in loss overcame any potential rivalries or differences. The book of Baruch, contrary to much of Second Temple literature, lacks any disputes over practice, outlook, or interpretation of history. The political, social, and religious conflicts that motivate the plot of the books of Ezra and Nehemiah receive no notice in Baruch so that the Judeans may be one before God in repentance, salvation, and restoration. Baruch’s all-embracing turn torward God provides a cogent example to the multiplicity of Christian churches all struggling with communal problems in the face of modern Western culture and the rich diversity of cultures and religions throughout the world.

The book of Baruch shares the inclination of both the biblical tradition and the modern world to see history as a coherent, intelligible whole. Baruch fills in the narrative of Israel’s exile, where details are scarce, and does so in a way that brings coherence, unity, and expectation to Israel’s history. To preserve Israel’s integrity in the face of Babylonian exile, the author of Baruch provides for the continuity of settlement, worship, and priestly institutions and thus mitigates the tragedy of the destruction. In a similar way, contemporary Christian modes of worship, behavior, fellowship, and social engagement must undergo reinterpretation and revitalization so that God’s work in the community may be felt in the world.

BARUCH 1:15–3:8

Prayer of Confession and Repentance

Overview

The Babylonian exiles’ prayer, which they send to Jerusalem and Judea (1:13–14), consists of two long sections: a communal confession (1:15–2:10) and a prayer of repentance (2:11–3:8). The first is a public admission of sin and an acknowledgment of just punishment. Unlike similar confessions, it is not addressed directly to God in the second person, but gives a more "objective," third-person description of sin that instructs Israel. The confession of sin is personalized by a hortatory use of "we," which invites Israel to acknowledge its failings. The second part is a prayer of repentance and a petition for mercy addressed directly to God in the second person. This combination of confession and petition is typical of Second Temple prayers and can be found in Ezra 9:6–15; Neh 1:5–11; 9:5–37; Daniel 9; the Prayer of Azariah (Dan 3:3–22 LXX); and the Words of the Luminaries (4Q504–506). Second Temple prayers and hymns frequently contain petitions for mercy, forgiveness of sins and deliverance from divine punishment and oppression; prayers of repentance and confessions of sin (see 4Q393), acceptance of divine punishment and acknowledgment of God’s justice; and reviews of Israel’s disobedience and of God’s fidelity to Israel.

Second Temple prayers developed from a variety of biblical literary forms, especially the communal lament, which is found in about forty psalms (e.g., Psalms 44; 74; 79; 80; 83), the book of Lamentations, and the prophets (e.g., Isa 63:7–19). The confession of sin can be found in a number of places (e.g., Psalms 51; 106; Jer 32:17–23). The classical lament contains at least three elements: (1) a description of Israel’s enemy, (2) Israel’s desperate situation because of the enemy, and (3) a petition to God for help or mercy. Some psalms complain so bitterly about Israel’s suffering that they essentially indict God for abandoning Israel. After the destruction of Jerusalem, a heightened consciousness of sin transformed reproaches against God into an acknowledgment and acceptance of just divine judgment and punishment. The prayer of petition (often introduced by the imperative "Hear" as in Bar 2:14, 16, 31; 3:2, 4) was bolstered by a prayer of repentance or confession of sin. Israel’s confession of its disobedience and acceptance of prophetic threats of punishment for sin are often balanced by a recollection of God’s past mercy and saving acts toward Israel and praise for God’s justice and aid. These Second Temple prayers still reflect the biblical covenant form: "1) confession of breach of covenant, 2) admission of God’s righteousness, 3) recollection of God’s mercies, and 4) appeal for mercy for God’s own sake."

Second Temple prayers share many literary characteristics and traditional attitudes, but do not have one strictly stereotypical form. They reflect the diverse circumstances of post-exilic Jewish communities and the vitality and creativity of the literary and liturgical tradition as it adapted to new circumstances by shifting away from classical biblical forms toward a great variety of expressions using traditional vocabulary and theology in new settings and combinations. The rich fund of hymns and prayers found in Second Temple literature, most recently in the Dead Sea Scrolls, shows that they were popular during the Second Temple period.

Was the prayer in Bar 1:15–3:8 possibly used in a public context? According to the narrative in Baruch, this prayer was supposed to be recited when the Judean community made its "confession in the house of the Lord on the days of the festivals and at appointed seasons" (1:14). The survival of a large number of these prayers in narrative contexts (e.g., Ezra 9; Daniel 9) and independently among the Dead Sea Scrolls (4Q393; 4Q507–509, parallel to 1Q34 and 34 bis) suggests that this popular prayer form may have been used in penitential settings. For example, the Qumran Community Rule (1QS 1–2; see also the Damascus Document 20:28–30) seems to reflect a communal confession of sins and plea for mercy as part of a covenant renewal ceremony. The confession and prayer of repentance in Bar 1:15–3:8 derives from this Second Temple tradition of public confession and repentance. However, since Bar 1:15–3:8 serves the overall theology and purposes of Baruch so thoroughly, it probably was a literary creation for this work rather than a pre-existing public prayer.

Though some have claimed that the prayer is loosely constructed, repetitive, and verbose, it is in fact carefully constructed with balanced parts and interlocking themes. The confession (1:15–2:10) begins and ends with similar laments (1:15–18; 2:6–10) and encloses a recital of Israel’s disobedience and punishment. The prayer of repentance (2:11–3:8) begins and ends with petitions (2:11–18; 3:1–8) and encloses a contrast of God’s threat of punishment for disobedience (2:19–26) with God’s promise of mercy (2:27–35). The confessions, descriptions of punishment, petitions to God, etc., are connected to one another by a rich web of language and themes that are repeated and developed in different contexts. The unifying language and themes make it unlikely that several earlier prayers have been combined, as some claim. Attempts to divide the prayer into a confession written by Baruch for those remaining in Jerusalem (1:15–2:5) and a prayer for the exiles (2:6–3:8) contradicts the author’s consistent treatment of all Israel as one.

The language, literary forms, and theology of the confession and prayer are based on the Hebrew Bible, especially the prayer in Daniel 9, the Baruch material in Jeremiah 32 and 36, and the deuteronomic theology found in Jeremiah, Deuteronomy, and the deuteronomic history. Most strikingly, Bar 1:15–2:18 follows closely the prayer of confession and request for forgiveness in Dan 9:4–19; from Bar 2:19 on, the Danielic material has been exhausted. In contrast to Bar 1:15–2:18, the prayer in Dan 9:4–19 addresses God directly and more concisely, with only a brief third-person description of what God has done in the middle (Dan 9:12–14). Baruch has expanded the Danielic prayer with language and thought drawn from Jeremiah and deuteronomic theology. Baruch has also changed the focus of the prayer from the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple to the sufferings of exile. In the end, though, the prayers in Daniel and Baruch are so similar that either one is dependent on the other or both draw on a lost source. Few argue that Daniel is dependent on Baruch, but no consensus has emerged on whether Baruch depends on Daniel or both on a common source. The question is further complicated because most agree that the prayer in Daniel 9 is an earlier literary unit that has been incorporated, perhaps with revisions, into Daniel. Thus Moore claims that both prayers could derive from the late fourth century bce, while Steck argues that Baruch depends both on the Danielic prayer and on its literary context in Daniel 9. In the end, both prayers were probably written in the midsecond century bce during the Maccabean period.

As has been noted, the author of Bar 1:15–3:8 has drawn heavily from the language and interpretations of Israel’s history as it is found in Jeremiah. For example, Jeremiah 32 has especially influenced Baruch. During the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, God instructs Jeremiah to purchase a family field (Jer 32:6–15) as a sign that Judah’s defeat will not be permanent. Jeremiah then prays to understand God’s purpose, reviewing the exodus, Israel’s disobedience, and the ongoing Babylonian attack on Jerusalem. God replies with a description of Jerusalem’s imminent defeat and destruction (Jer 32:26–35) and with a promise of restoration and a new covenant (Jer 32:27–44). Not just the words and phrases, but also the assumptions, theology, and attitudes in Jeremiah 32 have influenced the author of Baruch. Baruch also draws upon and fills in the Jeremianic narrative. For example, the transition from the description of Israel’s punishment to the promise of restoration (Jer 32:35–36) implies, but does not state, that Israel has repented. Baruch 1:15–3:8 expresses Israel’s repentance.

Behind both Jeremiah and Baruch lies the theology, language, and outlook of Deuteronomy. The theme of Baruch may be summarized by Deut 4:30–31:

In your distress, when all these things have happened to you in time to come, you will return to the Lord your God and heed him. Because the Lord your God is a merciful God, he will neither abandon you nor destroy you; he will not forget the covenant with your ancestors that he swore to them.

The language of the blessing and curses in Deuteronomy 28 and of the covenant in Deuteronomy 30 are especially rich as a source for Baruch. Though dozens of linguistic and theological parallels could be given, this commentary will be limited to major cross-references and concentrate on the internal coherence and integrity of Baruch.

BARUCH 1:15–2:10, CONFESSION OF THE JUDEAN COMMUNITY

Commentary

The prayer, sent by exiles in Babylon to be read aloud during the festivals, begins with a terse, blunt, and balanced description of the present relationship of Israel to God that acknowledges Israel’s fault and vindicates God:

To our Lord God righteousness,

but to us shame of faces

until this day.

(Bar 1:15a, author’s trans.)

Israel’s shame is neither a feeling of embarrassment nor a sense of personal guilt; it is, rather, a loss of honor of "face"—that is, proper and expected public standing. A shamed or dishonored person no longer could participate normally in social relationships or function as an integral part of the village or nation. In this case, Israel frankly admits its disordered and untenable relationship with the most important member of its social world, God. This admission, elaborated in 1:15–2:10, lays a foundation for the lengthy appeal to God in 2:11–3:8.

The shame includes all Israel throughout history: the people of Judea and the inhabitants of Jerusalem, their traditional leaders from the top down (kings, rulers, priests, and prophets), and finally their ancestors who were in the same unacceptable relationship with God as Israel is in the present (1:15–16). Baruch adopts the outlook of Jeremiah, who condemns everyone, including (false) prophets (Jer 32:32). This view is contrary to Dan 9:6, which omits the prophets. Israel’s shame derives from sin, disobedience, and failure to listen to God’s voice and live according to divinely given statutes (vv. 17–18; cf. Deut 9:23; Jer 9:13; Dan 9:8–10). The prayer follows the deuteronomic tradition in which Israel’s failings provide the stimulus for exhortation and prophecy.

The Greek verb for "negligent" (

ἐσχεδιάζομεν eschediazomen, 1:19), which occurs here only in the LXX, may also mean to be "hasty" or "careless," so that Israel is ironically "quick not to listen." As a result (Bar 1:20), the curses promised in Deut 28:15–68 for disobedience have "clung" to Israel (3:4; Deut 28:21, 60). (The expression "calamities and the curse" is more literally and grammatically rendered, "the evil things, namely the curse.") Although God spoke to Israel through the prophets (1:21; see also 2:20, 24), as God had through Moses (cf. the unfaithful, corrupt prophets of 1:16), Israel did not listen but instead rejected God through idolatry and evil behavior. God in turn confirmed and carried out (ἔστησεν estēse; ויקם wayyāqem) God’s word (2:1). That is, God is faithful in punishing unfaithful Israel, from the judges and kings of the Bible to the time of the author of Baruch.This lamentable history provokes a reflection from the author on the severity and uniqueness of the punishments associated with the destruction of Jerusalem (2:2–5). The reference to cannibalism (2:3) is threatened in the Bible (Lev 26:29; Deut 28:53; Jer 19:9) and is a stock horror story of sieges. The author shields himself somewhat from the horrors of the destruction and exile by referring to the exiles as "them" (2:4–5). But at the end of v. 5, the author again identifies himself and his audience (the NRSV inserts "our nation" in place of "we") as the sinners who failed to listen to God’s voice. This failure to listen appears frequently as the radical rupture in the relationship of people with God (1:19, 21; 2:10, 22, 24, 29; 3:4).

The confessional prayer ends just as it began, with an acknowledgment of God’s justice and Israel’s shame (2:6; cf. 1:15) and a summary of Israel’s punishments and refusal to repent (2:7–10; cf. 1:18–22). All the disasters suffered by Israel were threatened by God in Scripture (2:7), were kept ready or watched over by God (2:9; cf. Dan 9:14), and were actuated by God (2:9). In all this, God is just (2:6) as are all the demands God makes (2:9). The phrase "all the works which he has commanded us [to do]" (2:9) may also mean "all his actions which he has ordered against us." (See similar phrases in the prayers in Neh 9:33; Dan 9:14.) The final verse (2:10) repeats and summarizes the confession with which the prayer began: Israel has neither listened to God’s voice nor done what God commanded (cf. 1:18). They have shamed God and God’s honor—that is, God’s status as Creator and Ruler requires defense. Thus God has punished Israel, and in response Israel must honor God by acknowledging God’s justice and turning to God for help. This Israel does in its prayer for mercy and deliverance.

Some commentators understand 2:6–10 as the beginning of the following prayer, but this paragraph is still in first- and third-person speech, in contrast to 2:11–3:8, which is in the second person; and 2:6–10 summarizes and concludes (with an inclusio) the confession begun in 1:15. Israel’s full confession of its failure to listen and obey and of its sin and just punishment lead to an extended request for divine mercy and deliverance motivated by desperate need. (See Reflections at 2:11–3:8.)

BARUCH 2:11–3:8, PRAYER OF REPENTANCE FOR MERCY AND DELIVERANCE

Commentary

2:11–18. The prayer of repentance includes further confession and a plea for mercy addressed directly to God in the second person. The beginning (vv. 15–19) draws phrases and themes from the end of the prayer in Dan 9:15–19. However, Baruch’s prayer for restoration focuses on the people, in contrast to Dan 9:15–19, where the restoration of the city of Jerusalem is central to the author’s concerns. The introduction to the prayer of repentance (vv. 11–13) invokes the founding event of Israel’s relationship with God: liberation from slavery in Egypt, followed by memories of God’s benevolent power and Israel’s sins and just punishments. The language and theology of this appeal stand squarely in the deuteronomic tradition (e.g., Deut 6:21–23; Jer 32:20–21; Dan 9:15). The NRSV follows the Greek in stating that Israel has done wrong "against all your [God’s] ordinances" (v. 11), but the Hebrew of Dan 9:16 suggests that the original text may have connected that final phrase with the following sentence. If so, then Israel would be asking God to turn away from anger on the basis of God’s sense of justice: "Lord our God, by all your just actions let your anger turn away from us." At the end of the introduction (v. 13) the author cites other reasons for the exiles’ prayer: They are few in number, scattered, and under the control of other nations (see also 2:14, 23, 29–30, 32, 34–35; 3:7–8). This prayer will seek to overcome the distance between God and the people that has been opened up by sin, exile, and loss of autonomy.

The next two petitions (vv. 14–15 and vv. 16–18) appeal to God’s self-interest as a motive for listening to Israel’s requests. Since Israel and its people are called by God’s name (see 2 Sam 12:28 for the custom of imposing a ruler’s or an owner’s name upon something), and since all the world knows of God through Israel, then the nations that have captured Israel will think ill of God if the people die and cannot testify to God’s glory and justice. The people’s requests are modestly appropriate to their powerless position in exile. First, they desire to find favor in the sight of their captors (v. 14), a practical good sought in several other biblical texts (1:12; 1 Kgs 8:50; Ps 106:46; Ezek 8:9), and then they ask to remain alive so that they can praise God (v. 18): "The person who is deeply grieved, who walks bowed and feeble, with failing eyes and famished soul, will declare your glory and righteousness, O Lord" (Bar 2:18).

This latter request turns the tables on God by transforming a deuteronomic punishment into a petition in lieu of death. In Deut 28:62–67, Moses threatens that if Israel disobeys God, it will be left few in number and scattered among all peoples; here in v. 13 these things have happened. Deuteronomy further warns that God will give Israel "a trembling heart, failing eyes and a languishing spirit" and constant fear because their lives are threatened (Deut 28:65–67). Baruch, after pointing out that the dead cannot praise God (v. 17), cleverly accepts the promised grief, debilitation, and fear in order to avoid the threat of death (v. 18). The very limited goals of these petitions bespeak a long experience of exile and political powerlessness and contrast strikingly with many prophetic promises and apocalyptic visions of national restoration.

2:19–35. The author begins his plea for God’s mercy in v. 19 by confessing again that his ancestors and their kings did not act justly and by implicitly acknowledging that he has no right to God’s help. He substantiates this admission with a narrative of Judah’s disobedience, which led to the destruction of Jerusalem and the disinterring of their kings and ancestors by the victorious Babylonians. Baruch’s narrative draws upon the accounts and prophetic threats in Jeremiah.

The Hebrew expression used to ask for God’s mercy (lit., "throw down a plea for mercy [

ἔλεος eleos] before your face," 2:19) is found with similar Greek wording only in Dan 9:18 and in Jer 36:7; 37:20; 38:26; 42:2. Israel has been punished for disobeying prophetic commands (1:21; 2:24) to submit to Babylonian rule (cf. Jeremiah 27) by a miserable death from famine, war, and disease (Bar 2:25 and often in Jeremiah and elsewhere) and also by dishonor that continues up to the present, through the disinterment of royal bones (v. 24) and the ruin and decay of the Temple (v. 26). Jeremiah had predicted that King Jehoiakim’s corpse would be exposed to the elements (Jer 36:30) as punishment for his rejection and burning of the scroll of Jeremiah’s prophecies. The vague expression "you have made [the Temple] as it is today" (v. 26) refers to the Temple that was destroyed in the sixth century bce and perhaps also to the sad state of the Temple or its administration when Baruch was written.Baruch’s prayer and the poems in 3:8–4:4 and 4:5–5:9 do not end with punishment, but with God’s kindness and compassion toward Israel (v. 27). The Greek word translated as "kindness" (

ἐπιείκεια epieikeia) refers to fairness and clemency in applying the law in a court, and the word for "compassion" (οἰκτιρμός oiktirmos) refers to those people or situations deserving of pity because of the suffering or loss involved. God’s mercy was already promised and predicted in Scripture at the time when God told Moses to write down the law (Exod 24:2; Deut 31:9; cf. Josh 8:32). The "quotation" that follows (vv. 29–35) is not word for word from the Bible, but contains phrases and clauses from Moses’ teaching in Deut 4:30–31; 30:1–10; and numerous places in Jeremiah, especially chap. 32. The use of Moses and Jeremiah here is consistent with references to Moses and the prophets earlier (Bar 1:20–21; 2:2, 20). The repetition of God’s promises to Israel in a traditional form implies that God has already set the process in motion and that the end result of the promises is assured. Rejection of God’s commands has led to the scattering of the people among the nations and a diminution of their numbers (vv. 29–30), but in exile the people will recognize their God (vv. 30–32) and obey because they acknowledge the sins of their ancestors. In Baruch, the people have precisely recognized God and acknowledged their sin through confession and prayer. Just as rejection of God in the promised land led to its loss, so also now recognition of God in exile leads to a return to the land (vv. 34–35). The promises made to the patriarchs will be fulfilled again in the restoration of the people as inhabitants and rulers of the land. The cycle of history will be complete when God binds the people through a permanent covenant, never to exile them again (v. 35). Sin, which soured Israel’s relationship with God, has been overcome through this confession of sin, repentance, and remembering of God. Now all that is required is the return to the land of Israel.3:1–8. The final petition of the prayer returns the focus to the exigencies of present exile and recaptitulates many of the themes of the preceding prayer. Commentators have often understood this final section as an independent prayer because (1) it has a different tone; (2) it addresses God as the "Almighty" (vv. 1, 4 and nowhere else in Baruch; (3) it is spoken by the children of the original exiles (v. 7), not the Judean leaders and people listed in 1:13–16 or the original exiles themselves (2:13–14); and (4) it articulates Israel’s urgent need for deliverance from exile and oppression, in contrast to 2:14, which seeks only a lightening of oppression. These tensions may indicate that an earlier source was used, but vv. 1–8 now bring Israel’s confession and prayer of repentance to an acute and intense conclusion, preparing for the final two poems.

God is addressed for the first time as "Lord Almighty,"

Κύριος Παντοκράτωρ (Kyrios Pantokratōr) in Greek and יהוה צבאות (Yahweh Ṣĕbāʾôt) in Hebrew, by "a soul in anguish and a wearied spirit" appropriate to a lengthy exile. The prayer progresses expeditiously from a plea for mercy and a confession of sin (v. 2) to a striking contrast between God, who is permanently enthroned in heaven, and Israel, which is continually perishing (v. 3). The actors, their relationships, and the problem are patent and lead to a repeated, more urgent petition for help. The second half of the prayer begins with a repetition of the call in v. 2 for God to hear Israel (v. 4). In the Greek, Israel is characterized as "dying" or "dead" (מיתי ישׂראל mêtê Yiśrāʾēl) Israel. The Greek translator probably misread the Hebrew מתי (mĕtê), meaning "men" (Isa 41:14; NRSV, "people") as mêtê Iśrāʾēl, "the dead of Israel." Yet the Greek makes symbolic sense in this context (מיתי ישׂראל mêtê Iśrāʾēl), for "dying Israel" recalls 2:17, which reminded God that the dead cannot praise God. The exiles point out that they are the generation subsequent to those whose sins caused the destruction of Jerusalem and exile (v. 2). Although they concede that their parents did not listen to God, they call on God to hear them because the evils (the literal meaning of κακά [kaka], translated by the NRSV here and in 1:20 as "calamities"; cf. Deut 28:21, 60) that "clung" to their sinful parents have also clung to them.Baruch’s prediction at the end of chap. 2 that Israel would remember God and then repent is now fulfilled. Israel remembers and praises God (vv. 6–7) and calls on God, with ironic appropriateness, not to remember its ancestors’ sins (v. 5). The petitioners protest that they have fear of God in their hearts (v. 7) and have rejected their ancestors’ iniquity (v. 8; cf. v. 4), and they urgently remind God again of their social dislocation and disorder ("scattered, cursed, reproached and punished," v. 8). The Greek word for "punished" (

ὄφλησις ophlēsis) connotes a judicial penalty or fine in a lawsuit.In summary, Israel’s prayer of confession and repentance ends with a call to God to hear (vv. 2, 4) and to see (v. 8), but without a response and closure. God’s redemption of Israel will be dramatically recounted at the end of Baruch (chap. 5). In the meantime, since the people claim to fear God (v. 7), the author of Baruch continues with a wisdom poem (3:9–4:4), which, like all wisdom literature, presumes a sense of awe, reverence, and fear of God. The wisdom poem also explains more fully why Israel is suffering in exile and how it should act while waiting for God.

Reflections

Modern spirituality stresses positive attitudes and goals such as growth, fulfillment, relationships, and love. Confessing and repenting of sin, error, and failure unsettle us and clash with our positive religious sensibility. Believers in the lonely contemporary world spontaneously seek God’s love and promises of salvation. Unfortunately, many of us also seek to evade pervasive evil and the onerous labor of asking for forgiveness. Americans especially turn away too quickly from the pain and shame of sin and fail to envision a bright new future and a fresh start on the road to success. Our lack of self-esteem frequently prompts evasion and denial, rather than admission of responsibility or guilt. Few people know how to begin an apology or admit gracefully that they are wrong.

The confession and prayer of repentance in Baruch guides us through the necessary stages of healing and growth from acknowledging sin to admitting helplessness, calling on God, and repenting. The author of the confession cuts the knot of repentance in the fourteen English words that were cited at the beginning:

To our Lord God righteousness,

but to us shame of faces

until this day. (Bar 1:15, author’s trans.)

Frankly and openly, he contrasts human shame and failure with God’s integrity and honor. From this admission all else follows in Baruch, including forgiveness, the revelation of God’s law, renewed fidelity, the consolation of Jerusalem, and the return of the exiles.

In contrast to Baruch, many modern corporate and political leaders speak of moral, professional, and personal failure and evil in impersonal terms. They say, "Mistakes were made." But no name, least of all that of the speaker, appears. Sins that destroy body and spirit become lapses in judgment. The exposure of misdeeds arouses not a robust admission of wrongdoing, but attacks on the media or "whistleblowers," who are labeled enemies or liars.

The author of the confession in Baruch does not hide behind evasive rhetoric. Israel has refused to listen to and obey God from the exodus to the time of Baruch. God warned Israel, but the people did what they wanted. God responded with punishment. This concise history of Israel functions like the stories told at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings or like the feelings of participants in therapy sessions. No excuses, rationalizations, or extenuating circumstances can erase or hide the cold, painful facts of lives gone wrong, nor can they mitigate the destructive consequences to self, family, friends, and society.

Rigorous honesty, no matter how great the anguish, opens the way out. Paradoxically, the painful review of sin and guilt at the beginning of the prayer in Baruch brings coherence and consolation to the lives of those who ask for forgiveness. Authentic comprehension of the cause of the exile and Babylonian oppression opens the way for a different outcome. The rehearsal of disobedience and sin contrasts ironically and painfully with an urgent appeal for mercy from the very God who has been rejected. The refusal to hear God in the past (1:17, 21; 2:5) silently reproaches the petitioners even as it motivates their call for God to hear them now in their need (2:14, 16, 31; 3:2, 4). A stark awareness of God’s anger and an immediate experience of punishment permeate the prayer. Yet the petitioners’ very disarray and sense of loss turn them inevitably toward a restored community. A frank admission of fault sensitizes them to the most important things they have lost and seek to regain.

From talk shows to poetry readings, everyone complains about the disarray of society, the futility of work, the corruption of politics, and the collapse of the family. We blame impersonal bureaucracies, venal governments, "other" social groups and irrational, unknown forces for our misfortunes. Disconnected from our immediate world, we inevitably misunderstand the real causes of our confusion, alienation, and anxiety. Looking for a scapegoat, we lack responsibility and so, like children, cry out in frustrated impotence.

In Baruch, confession of sin and repentance make sense of Israel’s disasters. When we admit our failings, misunderstandings, weaknesses, and harmful, sinful behaviors, we begin to understand the chaos and suffering of life as a consequence of disobedience to the laws that were meant to give shape to a just society. By that very act we diminish the scope and power of disorder and confusion within ourselves and in the world around us. In Baruch, Israel mourns the lost Temple (2:26), the ignored Torah (2:28), the conquered land (2:34), and the exiled people (2:23, 35). As a result, these four—Temple, Torah, land, and people—became the pillars of Second Temple Judaism, appearing constantly in Jewish prayers, poems, and narratives, most especially in the final two poems of Baruch. Reconstruction of modern life awaits a similar, frank inventory of our sins and losses so that we may know what God has given us as a foundation for our lives.

BARUCH 3:9–4:4

Wisdom Admonition and Exhortation

Overview

This section of poetic wisdom admonition and exhortation differs significantly in style, terminology, genre, and background from the preceding prayer of confession and repentance; yet, it fits coherently into the argument of the book of Baruch as a whole. The admonition and exhortation teach Israel what to do after its confession and repentance by exploring the origins of sin and suggesting a better way to live through wisdom. The poem attributes the problem of sin and exile to the people’s abandonment of wisdom and their inability to find it on their own. It argues that the law, especially Deuteronomy, is wisdom itself. Wisdom has been given to Israel by God as a basis for a renewed life of fidelity, and it demands understanding and obedience.

The logical structure of the poem is relatively simple, though attempts to recover its poetic structure vary greatly because we do not have its Hebrew original. The sections of the wisdom poem in this commentary follow the flow of its argument rather than a hypothetical reconstruction of the poetic form. The poem begins with a rebuke of Israel for abandoning wisdom and a call to learn wisdom (3:9–14). The question of where wisdom is to be found (3:15) leads to a long section that argues that different groups of people and even the ancient giants have been unable to find wisdom (3:16–31). God, the Creator who knows wisdom and gives it to Israel in the law, solves the problem (3:32–4:1). The poem ends with an exhortation for Israel to accept wisdom (4:2–4) as the solution to Israel’s sinfulness and as the key to reestablishing a proper relationship with God.

This wisdom poem was probably written originally in Hebrew, though many scholars still hold that it was composed in Greek. It may have circulated independently before being modified and incorporated into Baruch. It uses language and thought found in biblical and Second Temple wisdom literature, rather than the prophetic language dominant in the other parts of Baruch. It also contains the deuteronomic terms and ideas that appear in all sections of Baruch. The wisdom poem refers to God by the generic Greek term for God,