DANIEL

Michael Rydelnik

INTRODUCTION

The book of Daniel is set during the Babylonian

captivity. The book opens after King Nebuchadnezzar’s first siege of Judah

(605 BC) when he brought Daniel and his friends to Babylon along with other

captives of the Judean nobility. Nebuchadnezzar assaulted Judah again in 597

BC and brought 10,000 captives back to Babylon. In 586 BC he once again

besieged Jerusalem, but this time destroyed the city and the holy temple and

exiled the people of Judah to Babylon. Daniel’s ministry began with the

arrival of the first Jewish captives in Babylon (605 BC), extended

throughout the Babylonian captivity (539 BC; see Dn 1:21), and concluded

sometime after the third year of the Medo-Persian king Cyrus the Great

(537/536 BC; see Dn 10:1).

Author. The critical view of the book of

Daniel is that it was written by a second-century BC Jewish author who chose

to use the name of the prophet Daniel as a pseudonym. This naturalistic

perspective denies the possibility of authentic foretelling. Since the book

contains many precise predictions of events in the second century BC,

critics think that it must have been penned after that time by someone other

than Daniel to appear to be predictive.

The traditional view maintains that Daniel the

prophet did indeed write this book. Internal testimony supports this claim.

In the text itself, several times Daniel claimed to have written visions

(8:2; 9:2, 20; 12:5). Passages containing third-person references to Daniel

do not dismiss the fact of his authorship, since other biblical authors at

times speak of themselves in the third person (for example, Moses in the

Pentateuch). Moreover, God speaks of Himself in the third person (Ex 20:2,

7). Other ancient authors, such as Julius Caesar in The Gallic Wars

and Xenophon in Anabasis, refer to themselves in the third person.

The prophet Ezekiel refers to the prophet Daniel (Ezk 14:14, 20; 28:3) as

well. Jesus Christ also attributes authorship of the book to Daniel (Mt

24:15).

Date. The critical view maintains a date of

165 BC in the Maccabean period, primarily because of the precise prophecies

related to that time period. It views the historical sections as mere

fiction, written much later than when the events allegedly transpired. R. K.

Harrison points out that this critical approach became the standard

understanding of the book so that "no scholar of general liberal background

who wished to preserve his academic reputation either dared or desired to

challenge the current critical trend" (R. K. Harrison, Introduction to

the Old Testament, [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1969], 1111).

The traditional view asserts that the book was

written just after the end of the Babylonian captivity in the late sixth

century BC. It holds that the book contains a factual recounting of events

from the life of Daniel as well as supernatural predictions of events that

took place during the intertestamental period and other prophecies that have

yet to be fulfilled.

The traditional understanding is supported by

manuscript evidence. Fragments from the book of Daniel were found

among the Dead Sea Scrolls—this would be unexpected if the work had just

been written. Linguistic evidence also supports the early date. For

example, the use of Aramaic in Daniel appears to fit a fifth- to

sixth-century BC date because it is parallel to the Aramaic of Ezra, the

Elephantine Papyri, and other secular works of that same period. The use of

Persian loanwords would not discredit the traditional view since Daniel’s

final composition would have taken place in the Persian period. It is not

surprising to find Greek words in Daniel since the Greek language had

already begun to spread even prior to the conquests of Alexander the Great.

Historical evidence also supports the early date. For example, Daniel

accurately described Belshazzar as coregent with another king (Nabonidus)

(cf. Dn 5:7, 16, 29), a fact that was lost until modern times. It appears

that the late date view is driven by a categorical rejection of supernatural

prophecy and not by objective evidence.

Some have argued that because the Jewish canon

of the Hebrew Bible places Daniel in the Writings, Daniel must have a later

date (165 BC). This wrongly assumes that the Hebrew canon developed

progressively and that the Writings were the last section. An argument

against this assumption is that an early book like Ruth, most likely written

in the preexilic period, was also included in the Writings. It is wrong to

view the canon as having a haphazard or progressive arrangement. Rather, it

was formed with literary purpose and structure. Therefore, Daniel is not in

the Writings because of a late date but because of its contents. It follows

Esther and precedes Ezra/Nehemiah (in the Jewish canon) because the

narratives of Daniel fit within the same time period as the events of these

other books. Also, Daniel was one of the wise men of Babylon and Persia, so

it made sense for those who ordered the canon to include his book in the

section of the Bible that contained wisdom literature. Regardless, the LXX

and Josephus (Contra Apion I, 38–39) both place Daniel among the

Prophets, which most English versions follow. Since Josephus preceded the

Masoretic division of the Bible by several centuries, its placement in the

Writings has no bearing on its date.

Purpose and Theme. The theme of the book of

Daniel is the hope of the people of God during the times of the Gentiles.

The phrase, "the times of the Gentiles," used by Jesus (Lk 21:24), refers to

the time period when the Jewish people lived under ungodly, Gentile, world

dominion, between the Babylonian captivity and the Messiah Jesus’ return.

The hope that the book promotes is that at all times "the Most High God is

ruler over the realm of mankind" (Dn 5:21). The book’s purpose was to exhort

Israel to be faithful to the sovereign God of Israel during the times of the

Gentiles. Daniel accomplishes this by recounting examples of godly trust and

pagan arrogance, as well as predictions of God’s ultimate victory.

The genre of Daniel is narrative, defined as

"the recounting of events for the purpose of instruction." This narrative

contains history, prophecy, and apocalyptic visions. Apocalyptic literature

refers to revelation by God given through visions and symbols with a message

of eschatological (end-time) triumph. Although Daniel contains apocalyptic

elements, it is not an apocalyptic book. Rather it is a narrative with

apocalyptic visions included.

Some have noted that the book of Daniel

contains both history (chaps. 1–6) and prophecy (chaps. 7–12) and divide the

book accordingly. However, a better way to view the structure of the book is

based on the two languages it uses: Dn 1:1–21 (Hebrew); Dn 2:1–7:28

(Aramaic); and Dn 8:1–12:13 (Hebrew). The Hebrew sections pertain primarily

to the people of Israel, while the Aramaic part, using the international

language of that time, demonstrates God’s dominion over all the Gentile

nations. (See the chart "Structure of the Book of Daniel.")

Background. The covenantal background of

Daniel relates to God’s unconditional promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob

and their descendants (Gn 12:1–7; 13:14–15; 15:18; 17:7–8; 26:2–3; 28:13;

35:12; 1Ch 16:16; 2Ch 20:6–7). When God added the Mosaic law, He expanded

the land promises made to the patriarchs with a land covenant that promised

the people of Israel material blessing in the land of Israel if they obeyed

the law (Dt 28:1–14). However, if Israel disobeyed, God promised that He

would discipline the nation. If they still disobeyed, God promised to drive

them from the land of Israel into captivity (cf. Dt 28–30, especially

28:63–68). Despite the discipline of dispersion, God swore that He would

never break his promises to Israel (Dt 4:31). Further, He promised that in

the last days He would give Israel a circumcised heart and regather the

Jewish people from all the lands in which they were scattered (Dt 4:30;

30:1–10).

The events in the book of Daniel occurred

during the dispersion of the Jewish people to Babylon, and many of the

prophecies pertain to their ultimate regathering at the end of days.

Contribution. Daniel’s book establishes the

validity of predictive prophecy and lays the foundation for understanding

end-times prophecy as well as the book of Revelation in the NT. But, most

important, it emphasizes that the Lord God has dominion over all the

kingdoms of the earth, even in evil days when wicked empires rule the world.

Two key words in the book are king (used 183 times) and kingdom

(used 55 times). Above all, Daniel teaches that the God of Israel is the

Sovereign of the universe, "For His dominion is an everlasting dominion, and

His kingdom endures from generation to generation" (Dn 4:34).

Structure of the Book of Daniel

| History (1:1-6:28) |

Prophecy (7:1-12:13) |

| The Godly Person in the Times of the Gentiles

(1:1-2:3) |

God’s Sovereignty over the Times of the

Gentiles (2:4-7:28) |

God’s People Israel in the Times of the

Gentiles (8:1-12:13) |

| HEBREW |

ARAMAIC |

HEBREW |

OUTLINE

I. The Godly Remnant in the Times

of the Gentiles (1:1–21; in Hebrew)

A. Daniel and His Friends in

the Babylonian Captivity (1:1–7)

B. Daniel and the King’s Food

(1:8–16)

C. Daniel and the Lord’s Reward

(1:17–21)

II. God’s Sovereignty over the

Times of the Gentiles (2:1–7:28; in Aramaic)

A. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream and

the Wise Men of Babylon (2:1–49)

1. The King’s

Disturbance (2:1–3)

2. The Wise Men’s

Difficulty (2:4–11)

3. The King’s Decree

(2:12–13)

4. Daniel’s Delay

(2:14–16)

5. Daniel’s Prayer and

Praise (2:17–24)

6. Daniel’s Revelation

and Interpretation before the King (2:25–45)

7. The King’s Response

to the Dream and its Interpretation (2:46–49)

B. Daniel’s Friends and the

Fiery Furnace (3:1–30)

1. The King’s Demand to

Worship the Statue (3:1–7)

2. The Young Men’s

Refusal to Worship the Statue (3:8–23)

3. The Lord’s

Deliverance from the Fiery Furnace (3:24–27)

4. The King’s

Recognition of the God of Israel (3:28–30)

C. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride,

Madness, and Repentance (4:1–37)

1. The Prologue: A

Declaration of Praise (4:1–3)

2. The Story: A Dream

Comes to Pass (4:4–34a)

a. The King’s Dream

(4:4–18)

b. Daniel’s

Interpretation (4:19–27)

c. The Dream’s

Fulfillment (4:28–34a)

3. The Epilogue: A

Declaration of Sovereignty (4:34b–37)

D. Belshazzar’s Feast and the

Writing on the Wall (5:1–31)

1. The Feast of the

King (5:1–4)

2. The Writing on the

Wall (5:5–9)

3. The Advice of the

Queen (5:10–12)

4. The Meeting with

Daniel (5:13–29)

5. The Fall of Babylon

(5:30–31)

E. Daniel in the Lions’ Den

(6:1–28)

1. The Plot against

Daniel (6:1–9)

2. The Prosecution of

Daniel (6:10–14)

3. The Punishment of

Daniel (6:15–18)

4. The Protection of

Daniel (6:19–24)

5. The Praise of

Daniel’s God (6:25–27)

6. The Prosperity of

Daniel (6:28)

F. Daniel’s Vision of the Four

Beasts, the Ancient of Days and the Son of Man (7:1–28)

1. Daniel’s Vision

(7:1–14)

2. The Angel’s

Interpretation (7:15–28)

III. God’s People Israel in the

Times of the Gentiles (8:1–12:13; in Hebrew)

A. Daniel’s Vision of the Ram

and the Male Goat (8:1–27)

1. The Vision of the

Ram and the Goat (8:1–14)

2. The Interpretation

of the Vision (8:15–27)

B. Daniel’s Prayer and Vision

of the Seventy Weeks (9:1–27)

1. Daniel’s Prayer of

Contrition (9:1–19)

2. Daniel’s Vision of

the Seventy Weeks (9:20–27)

C. Daniel and His Final Vision

(10:1–12:13)

1. Daniel’s Reception

of the Vision (10:1–11:1)

a. The Setting of

the Vision (10:1–3)

b. The Messenger of

the Vision (10:4–9)

c. The Hindrances

to the Vision (10:10–13)

d. The Purposes of

the Angelic Visit (10:14–11:1)

2. The Angel’s

Explanation of the Vision of Persia, Greece, and the

False Messiah (11:2–12:3)

a. The Predictions

of the Persian to the Maccabean Periods

(11:2–35)

(1) The

Predictions about the Persian Kings (11:2)

(2) The

Predictions about Alexander the Great

(11:3–4)

(3) The

Predictions of the Hellenistic Period

(11:5–35)

(a) The

Period of the First Seleucids and

Ptolemies (11:5–6)

(b) The

Period of Ptolemy III (11:7–9)

(c) The

Period of Antiochus III (11:10–19)

(d) The

Period of Seleucus IV (11:20)

(e) The

Period of Antiochus IV (11:21–35)

b. The Predictions

of the End of Days (11:36–45)

c. The Comfort of

the Chosen People (12:1–3)

3. The Angel’s Final

Instructions to Daniel Concerning His Prophecies

(12:4–13)

a. The Sealing of

the Book (12:4)

b. The Time of the

End (12:5–13)

COMMENTARY ON DANIEL

I. The Godly Remnant in the Times of the Gentiles

(1:1–21; in Hebrew)

The first chapter of Daniel serves as an

introduction to the entire book, identifying its setting, Babylon, and the

main characters of the narrative, particularly Daniel. Since the book is

designed to urge Israel to remain faithful to God despite living under

ungodly, Gentile, world dominion, the first chapter demonstrates how

faithfulness is to be maintained. Daniel and his friends represent Israel’s

faithful remnant that remain true to the Lord despite the pressures of a

pagan society.

A. Daniel and His Friends in the

Babylonian Captivity (1:1–7)

1:1. While Daniel records that these events

took place in the third year of the reign Jehoiakim, Jeremiah writes

that it was in the fourth year (Jr 25:1, 9; 46:1). Most likely Daniel used

the Babylonian system, which did not count a king’s year of accession to the

throne, while Jeremiah used the Israelite system of counting, which did

include the accession year, thus making it the fourth year. The events took

place during the accession year of Nebuchadnezzar (whose name means O god

Nabu, protect my son), king of Babylon (605–562 BC), apparently when he

was still coregent with his father and just after his victory in the battle

of Carchemish (605 BC, on the modern border of northwest Syria and southeast

Turkey). This battle established the Babylonian Empire’s dominance and ended

the Assyrian Empire’s role as a world power.

1:2. Although Nebuchadnezzar viewed his

defeat of Judah as a victory for his gods, Daniel recognized that it was

the Lord who gave Jehoiakim king of Judah over to the Babylonians

(cf. 2Ch 36:5–6). The secular ancient historian Berosus (Hellenistic-era

Babylonian writer, third century BC) mentioned these events when he wrote

that Nebuchadnezzar conquered Hatti-land (meaning Syro-Palestine). After

this initial conquest of Judah, Nebuchadnezzar would take more captives in

597 BC and then destroy Jerusalem and exile Judah to Babylon in 586 BC.

The Babylonian captivity fulfilled the covenant

God had made with Israel when they were about to enter their land (Dt

28–30). In it, God promised that if Israel obeyed His commandments, He would

bless them in the land of Israel. However, if they disobeyed, God assured

Israel that He would discipline them with expulsion from the land. Just as

Moses had foretold (Dt 31:29), Israel and Judah, for the most part,

disobeyed the law, engaging in idolatry (Jr 7:30–31; 16:18), and neglecting

the Sabbath and sabbatical years (Jr 34:12–22). So the Lord expelled the

northern tribes of Israel from the land by the hand of the Assyrians (721

BC) and the southern tribes of Judah to Babylon.

At the time of Nebuchadnezzar’s first invasion,

the king took vessels of the house of God (Dn 1:2; 2Ch 36:7)

fulfilling what Isaiah had predicted when Hezekiah had shown the temple

treasures to the Babylonian king a century before (cf. Is 39:2, 6).

Nebuchadnezzar brought these to the land of Shinar, using the old

word for Babylon as an allusion to the rebellious behavior surrounding the

original building of the city and tower of Babel (Babylon) in Genesis (Gn

11:1–9).

1:3–5. The king ordered that some of the

nobility of Judah be brought to Babylon to be trained so they could serve as

leaders when Nebuchadnezzar would take all of Judah captive. Ashpenaz,

described as chief of his officials, literally means "chief of the

eunuchs." Since by this time the word had come to mean "royal official,"

most likely Ashpenaz was not a eunuch, nor did he make Daniel and his

friends literal eunuchs.

Although Daniel and his friends were called

youths, the Hebrew word literally means "children" or "boys." Here it

probably refers to teenagers of around age fifteen. The Judean captives were

to learn the literature and language of the Chaldeans, a reference to

an ancient university-style education in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Aramaic. At

that time, Babylon was the most cosmopolitan city and the seat of academia

in the known world. They were also to be given the king’s choice food

and wine, indicating their privileged status as counselors in

training, despite being captives.

1:6–7. To assimilate the Judean captives,

the commander of the officials assigned new names to them; and to Daniel

("God is My Judge") he assigned … Belteshazzar ("Bel Protect

Him"), to Hananiah ("God Has Been Gracious") Shadrach ("The

Command of Aku"), to Mishael ("Who Is What God Is?") Meshach

("Who Is What Aku Is?") and to Azariah ("The Lord Has Helped"),

Abed-nego ("Servant of Nebo"). These new Chaldean names replaced their

Hebrew names, exchanging those that referred to the true God of Israel with

others that referred to the false gods of Babylon.

B. Daniel and the King’s Food (1:8–16)

1:8. Daniel made up his mind that he would

be faithful to God’s law even in a foreign land. Made up his mind

literally means, "set upon his heart" and refers to a deep inner resolve.

Daniel decided that he would not defile himself with meat from the

king’s table because the Babylonian diet at that time included nonkosher

meat such as horseflesh and pork. With regard to the wine, Daniel

would not want to drink what had been offered to Babylonian gods as a

libation. So he asked Ashpenaz for permission to abstain from the royal diet

so that he might not defile himself.

1:9–10. God gave Daniel favor and

compassion with Ashpenaz, indicating that it was not merely Daniel’s

winsome personality but divine intervention. Nevertheless, the Babylonian

official risked his own life if Daniel and his friends were to look more

haggard (lit., "thin") than the other captives because of their diet. In

that culture, appearing thin was a sign of illness, not health. If the four

young Jewish captives were deemed ill because of mistreatment by Ashpenaz,

Nebuchadnezzar would likely kill him, since the king was notorious for

decreeing death for those who displeased him (2:12; 3:13–15).

1:11–14. Daniel demonstrated his wisdom by

asking the overseer (better translated "guardian," since he was there

to protect and provide care for the youths) whom Ashpenaz had

assigned to them if they could eat a diet of vegetables and water

for a trial period of ten days. The word for vegetables refers

to that which grows from seed and would include vegetables, fruits, and

grains. The guardian agreed to the experiment, after which he would observe

the appearance of the youths compared to those eating the king’s

choice food.

1:15–16. At the end of ten days Daniel and

his friends looked fatter (i.e., healthier) but this is not a

biblical endorsement of vegetarianism (cf. Gn 9:3). Rather, God in His

providence made them healthy and strong so they could remain faithful to the

Lord. Since they were fit, they were allowed to continue their diet.

C. Daniel and the Lord’s Reward (1:17–21)

1:17. Daniel and his friends received

several rewards for their faithfulness to God. First, they were granted

superior wisdom. All gifts come from God but these four youths

received a special endowment of knowledge (referring to academic

skill) and intelligence (meaning "good sense"). Additionally,

Daniel even understood all kinds of visions and dreams, a point included

to show Daniel’s prophetic ability and superior gifting as well as to

prepare the reader for the events in the next chapter and the rest of the

book.

1:18–19. As a second reward for their

faithfulness, God granted Daniel and his friends special service to the

king. At the end of their education, King Nebuchadnezzar talked with them

and found them superior to all the other recent graduates of the King’s

academy. As a result, they entered the king’s personal service at the

king’s court.

1:20–21. God gave yet a third reward for

faithfulness to Daniel and his friends—a successful ministry. This is

evident in that the king found their counsel significantly superior (ten

times better) to that of the wise men of Babylon.

Throughout the book of Daniel, there occur six

different expressions for the king’s counselors. The first two, used here,

are magicians and conjurers. The word magician comes from a

root that means "engraver" and refers to those who engraved Babylonian

religious activities and astrological movements of the stars onto clay

tablets. The word conjurer refers to those who used spells and

incantations to communicate with the spirit world. No wonder then that

Daniel and his friends, by avoiding such occult practices and instead

seeking wisdom from the true God, were wiser than the king’s pagan

counselors.

Daniel’s successful ministry is also evident in

the length of his service. He lived to see the end of the exile, serving the

Babylonian kings until the first year of Cyrus the king (539 BC) of

Persia. Once the Persian Empire conquered the Babylonians, Daniel continued

as a counselor to the Persian king (cf. 10:1; 536 BC), resulting in more

than 70 years of service.

In 1924, in an event made famous by the 1981

movie Chariots of Fire, Olympic runner Eric Liddell sat out a race

because of his convictions as a follower of Jesus Christ. Later on, as he

prepared to run the 400-meter race, a man slipped him a note that contained

the words of 1Sm 2:30, "Those who honor Me I will honor." Liddell won the

gold medal and broke the world record for that race at that time. As it was

true for Liddell, for Daniel and his friends, and for the faithful remnant

of Israel, it will be true for any follower of Christ—the Lord will honor

those who honor Him.

II. God’s Sovereignty over the Times of the

Gentiles (2:1–7:28; in Aramaic)

Having portrayed Daniel and his friends as

models of the way the godly remnant is to live in the times of the Gentiles

(Dn 1:21), the book of Daniel next addresses (in chaps. 2–7) God’s continued

ultimate rule over the world despite Gentile world dominion. Since chaps.

2–7 pertain to God’s revelation about the Gentile nations, they were written

in Aramaic, the international language in those days. The structure of this

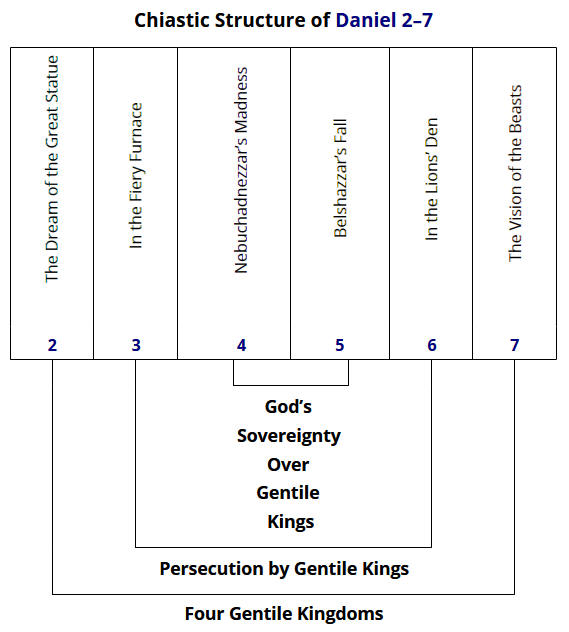

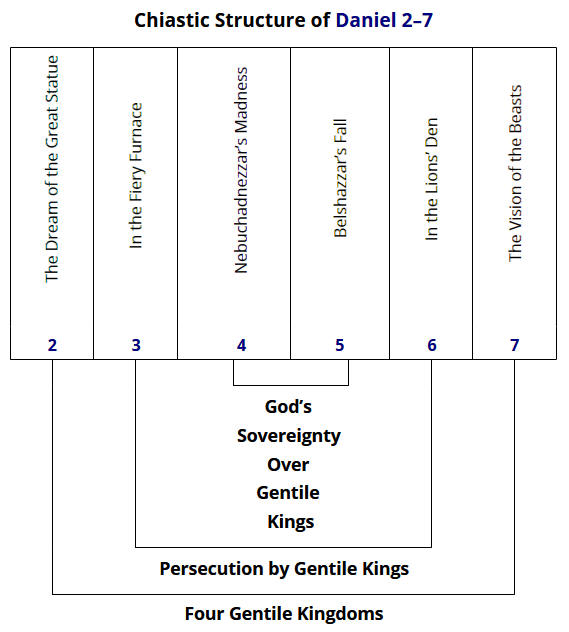

section is chiastic (A B C C’ B’ A’) with chaps. 2 and 7 each referring to

the four kingdoms of this world, chaps. 3 and 6 dealing with persecution by

Gentile kings, and chaps. 4 and 5 containing God’s special revelation to

pagan kings.

Chapter 2 tells the story of King

Nebuchadnezzar’s disturbing dream of a great statue (2:31) and

Daniel’s revelation and interpretation of it. In so doing, it reveals the

empires that would dominate Israel and the world during the times of the

Gentiles. The primary message of chap. 2 is that the God of Israel is

greater than the greatest of men.

A. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream and the Wise Men

of Babylon (2:1–49)

1. The King’s Disturbance (2:1–3)

2:1. The chapter opens with King

Nebuchadnezzar having had troubling dreams, and therefore he called

upon his wise men to interpret them for him. Since it is later revealed in

the chapter that there was only one dream, the plural used here indicates

that the king had a recurring dream. Since Nebuchadnezzar considered the

dreams significant, he was troubled by them and could not sleep.

The events of Dn 2 took place in the second

year of Nebuchadnezzar’s reign, which would appear to be a

historical contradiction in that Daniel’s three-year training program (1:5)

began in Nebuchadnezzar’s first year (1:1). The problem is resolved if, as

is likely, Daniel was using Babylonian reckoning: Daniel would have arrived

as a captive and entered his first year of training during the year reckoned

as Nebuchadnezzar’s accession year (605–604 BC); Daniel’s second year of

training would have been during the year reckoned as the first year of

Nebuchadnezzar’s reign (604–603 BC); Daniel’s third and final year of

training would have been during the year reckoned as the second of

Nebuchadnezzar’s kingship (603–602 BC). Therefore, the king sought

interpretation of his dreams in 602 BC, shortly after Daniel had completed

his three-year education.

2:2–3. As a result of the king’s disturbing

dreams he called for the court wise men to interpret for him. (For the

meaning of magicians and conjurers, see notes on 1:20–21.) The

Hebrew word used for sorcerers comes from the Akkadian word meaning

"practitioners of sorcery or witchcraft." The word Chaldeans is both

a general ethnic term for the Babylonian people and a specific term for

priests who served as astrologers, soothsayers, and wise men in the king’s

government. It is used in the secondary sense here, referring to the king’s

astrologers/wise men.

2. The Wise Men’s Difficulty (2:4–11)

2:4. The text states, using Hebrew, that

the Chaldeans spoke to the king in Aramaic. Although this is the actual

language with which they spoke to the king, the words in Aramaic also

function as a literary marker. At this point in the narrative, the language

switches from Hebrew to Aramaic and continues in Aramaic until 7:28.

2:5–6. The king demanded that the wise men

not only interpret the dream but that they also reveal its contents. Failure

to meet the king’s conditions would bring death to all the royal counselors

whereas successful identification and interpretation of the dream would

bring the wise men great honor and reward.

Some versions translate the phrase the

command from me is firm as "the dream is forgotten." But to do so, they

must emend (change the letters of) the Aramaic text. It is better to keep

the text as it is and translate it as referring to the certainty and

finality of the king’s demand. Nebuchadnezzar withheld the facts of the

dream not because he could not remember them, but because he wanted to test

his wise men.

2:7–10. The wise men repeated their request

for the king to reveal the dream to them. Yet the king was skeptical of his

royal counselors—he sensed that they claimed supernatural knowledge without

supernatural ability. Thus, Nebuchadnezzar demanded that they disclose what

could only be known by supernatural revelation. The counselors insisted that

this sort of request was unprecedented and that not a man on earth

could provide such knowledge. Their objection provides a narrative

introduction for Daniel’s entrance into the story as the man who could and

would receive supernatural revelation directly from God and thereby disclose

and interpret the dream.

2:11. The wise men admitted that what the

king wanted could only be obtained through the gods whose dwelling

place is not with mortal flesh. This is a candid confession that despite

all their incantations, magic, and astrology, they were not capable of

receiving supernatural revelation.

3. The King’s Decree (2:12–13)

2:12. The king became indignant and very

furious at the failure of his counselors to identify his dream. The

words wise men are used as a general term for all the king’s

counselors who, except for the Jewish captives, gained their knowledge via

occult means.

2:13. Daniel and his friends were also

subject to execution only because they were in the class of wise men, not

because they had participated in any of the discussions with the king. They

had likely avoided associations with the wise men to prevent being tainted

by their occult practices. Moreover, they were probably not previously

consulted because of their relative youth and inexperience, having only just

been appointed to government service.

4. Daniel’s Delay (2:14–16)

2:14–16. When the captain of the king’s

bodyguard (a word that would be better translated "executioners") came

to slay Daniel with the other wise men, Daniel asked why the king’s

decree was so urgent (or more accurately, "so harsh" as in the

HCSB). He then requested the king to grant him time, with the full

confidence that he would declare the interpretation to the king.

Unlike the other wise men, Daniel was not stalling. He had full confidence

that the God of Israel would reveal both the contents and meaning of the

dream to him.

5. Daniel’s Prayer and Praise (2:17–24)

2:17–19. Daniel informed his Jewish

companions of his need, and then together they sought help from the true

God of heaven. The title God of heaven is used four times in this

chapter (2:18, 19, 37, 44) and nowhere else in the book. It is a fairly

common name for the God of Israel in the postexilic writings (Ezr 1:2;

5:11–12; 6:9–10; 7:12, 21, 23; Neh 1:4–5; 2:4, 20) although it is not

limited to this period (cf. Gn 24:3, 7; Jnh 1:9). This chapter uses this

title to emphasize that only the God of heaven is omniscient (cf. Dn

2:20–22) and capable of revealing this mystery even as the pagan wise

men recognized (2:10–11). Moreover, Babylonians worshiped the luminaries but

the God of Israel was over all of them, hence called the God of heaven.

The word mystery refers to a secret that can only be known by divine

revelation. In response to their prayers, the dream

was revealed to

Daniel.

2:20–23. When God revealed the king’s

dreams, Daniel "blessed the God of heaven" (v. 19). Daniel’s song of praise

emphasizes that God is sovereign over the political affairs of humanity

because He controls the times and the epochs and removes

kings and establishes kings (v. 21). Moreover, Daniel recognizes that

God alone can give revelation by giving wisdom to wise men and by

revealing profound (lit., "deep") and hidden things, even the

king’s mysterious dream. Daniel was careful to give thanks and praise

the God of his fathers, recognizing that the ability to

interpret dreams did not generate from within himself but rather his

wisdom and power came as a gracious gift from God.

The point of the first half of chap. 2 is that

the God of Israel is greater in wisdom than the greatest of men, since He

was able to reveal the king’s dream, with its sovereign plan for the

nations, to His servant Daniel. The God of heaven is vastly superior to all

the great Babylonian Empire’s false gods, who were not able to reveal the

king’s dream to all the wise men of Babylon.

2:24. With his knowledge from God, Daniel

showed his compassion for his pagan colleagues, telling the executioner not

to destroy the wise men of Babylon. He also told the king’s

executioner that he would declare the interpretation, and by

implication, the contents of the dream to the king.

6. Daniel’s Revelation and Interpretation

before the King (2:25–45)

2:25–27. Having been brought to the king

and asked if he was able to make known … the dream … and

its interpretation, Daniel asserted that no pagan soothsayer could

declare it. The word translated diviners contains the idea of

"cutting" or "determining" and refers to a person who is able to determine

another’s fate.

2:28. Daniel attributed revelation to God

alone, who is able to reveal mysteries. His statement that God has revealed

what will take place in the latter days indicates that the king’s

dream would find its complete fulfillment only in the end times.

2:29–30. Daniel gave glory to God, who

alone is omniscient. Thus, He reveals mysteries and can disclose

what will take place in advance. Daniel was also self aware, recognizing

that he was merely an instrument of God, not someone with more wisdom than

any other living man.

2:31–45. Daniel described the king’s dream

of a single great statue (2:31–34), consisting of several parts. Each

part was made of different elements and represented a different empire in

historical succession. The head of that statue was made of fine gold

(2:32a) and represented the kingdom of Babylon (605–539 BC) (2:37–38).

Its breast and its arms were silver (2:32b) and symbolized the

Medo-Persian Empire (539–331 BC) (2:39a). Its belly and thighs were

bronze (2:32c) and stood for the Greek Empire (331–146 BC) (2:39b).

The legs were iron (2:33a) and referred to the Roman Empire

(146 BC–AD 476 in the West and 1453 in the East) (2:40). The feet were mixed

of iron and clay (2:33b) and represented a yet future

continuation or revival of Rome (2:41). It will divide into ten parts but

with less cohesion than the original Roman Empire (2:42–43). The material of

each section of the statue decreases in value but increases in strength. The

decreased value may refer to the decline of morality or lessening political

influence with each succeeding kingdom. The increased strength of the metals

refers to the harsher domination each successive kingdom would impose.

Daniel also described a stone … cut out without hands which

would shatter the statue (2:34). It represents a final kingdom that would

grow into a great mountain and fill the whole earth—this is the

kingdom of God (2:35, cf. v. 44–45).

Critical scholars, primarily because of their

denial of predictive prophecy, divide the four kingdoms into Babylon, Media,

Persia, and Greece (alleging that the book Daniel was written in 165 BC so

it could not have foreseen the Roman Empire). This interpretation is

doubtful because of its historically inaccurate division of the Medo-Persian

Empire into two separate empires, a division that is rejected even within

the book of Daniel itself (cf. 8:20 where the lopsided ram represents the

unified Medo-Persian Empire).

A select few interpreters, while maintaining a

sixth-century date for the book of Daniel, hold an alternative view that the

four kingdoms are to be identified as the Assyrian, Median, Medo-Persian,

and Greek Empires (cf. John H. Walton, "The Four Kingdoms of Daniel,"

Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 29.1 [Mar 1986]: 25–36).

This is certainly incorrect in that Daniel tells Nebuchadnezzar, king of

Babylon and founder of the Babylonian Empire, that he represents the first

kingdom (you are the head of gold) (2:38). Moreover, to justify this

alternative view, Assyria and Babylon must be conflated into one empire. But

the book of Daniel ignores Assyria and treats Babylon as the first kingdom

of the times of the Gentiles.

Most interpreters who accept the reality of

predictive prophecy view the four kingdoms as Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece,

and Rome. Rome is then conquered by the kingdom of God. In seeing the fourth

kingdom as Rome, these interpreters assert different opinions about the

meaning of the stone. Some view it as a spiritual kingdom, embodied in the

Church, which gradually conquered the Roman Empire. Others view it as a

future, earthly kingdom, to be established when Messiah Jesus returns and

institutes his physical rule that will fill the whole earth (2:35)

and never be destroyed (2:44). According to this view, the Roman

Empire will continue to exist until the end of days. According to some, the

Roman Empire continues through its persistent influence in Western

Civilization, existing until the end of days and the establishment of the

kingdom of God. A more likely explanation is to recognize a prophetic gap,

beginning with the fall of the Roman Empire (Rome I) and lasting through the

establishment of a revived Roman Empire at the end of days (Rome II). The

leader of this kingdom will be the little horn of Dn 7:8, 24–25. The

destruction of this last phase of the Roman Empire will come with the

establishment of the kingdom of God.

The evidence that there will be a literal,

earthly, end-of-days kingdom of God and not merely the Church spiritually

overtaking human governments is, (1) that all the previous kingdoms depicted

in the statue were earthly; (2) that there was no coalition of conquered

kings or kingdoms as described in 2:41–42 in the Roman Empire at the

Messiah’s first advent as would be required if the Church were the kingdom;

(3) that the stone, which represents the kingdom of God, destroys earthly

kingdoms, yet the Lord Jesus did not do this at His first advent; (4) that

the advent of the kingdom of God is described as a sudden overturn of

earthly kingdoms, not the gradual transformation through the influence of

the Church, and (5) that this vision is parallel to the four beasts

described in chap. 7. All agree that in chap. 7 the kingdom arrives with the

return of Jesus the Messiah—so should it be the same with the coming of the

kingdom of God here in chap. 2 (cf. Stephen R. Miller, Daniel, NAC,

edited by E. Ray Clendenen [Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 2003], 100–101).

Daniel’s second chapter demonstrates that the

God of Israel is greater than the greatest of men. In 2:1–24, it shows that

He is greater in wisdom than all. In the second half of the chapter

(2:25–45) it emphasizes that the God of Israel is greater in power than all

the great earthly kings and kingdoms. In the end, God will establish His

kingdom that will never be shaken.

7. The King’s Response to the Dream and

its Interpretation (2:46–49)

2:46–47. The king’s initial response was to

give homage to Daniel, but he also recognized that God was the source

of Daniel’s supernatural knowledge. Although King Nebuchadnezzar gave honor

to the Lord as one of many gods, even as God of gods and Lord of

kings, he did not yet recognize the God of Israel as the one and only

true God. He merely included the God of Israel in his pantheon of gods.

2:48–49. The ending note that the king

appointed Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-nego over the administration of the

province of Babylon provides the setting for the events that will be

described in the following chapter.

Even as Daniel previously praised the God of

heaven upon the revelation of the dream (2:20–23), so the king also

responded to Daniel’s revelation of his dream with an outburst of praise to

God (2:47). Worship should be the response of any follower of the Messiah

Jesus when encountering God’s supernatural revelation in His Word, the

Bible. Daniel expresses it well: "Let the name of God be blessed forever and

ever, for wisdom and power belong to Him" (2:20).

B. Daniel’s Friends and the Fiery Furnace

(3:1–30)

The events of Dn 3 probably took place shortly

after Daniel explained the king’s dream (cf. Dn 2) although some have

estimated that it could have been 10 or even 20 years later. Babylonian

records indicate that there was a revolt against Nebuchadnezzar during the

tenth year of his reign, and so this may have led to the king’s desire for

the loyalty test described here. The purpose of this chapter was to give the

faithful remnant of Israel a model of standing firm for the God of Israel in

the face of pagan Gentile oppression.

1. The King’s Demand to Worship the Statue

(3:1–7)

3:1. Nebuchadnezzar made an image of

gold, much like a colossus, not of solid gold but more probably overlaid

with it. Most likely, this statue reflects the king’s desire to have an

actual replica of the image he saw in his dream (cf. 2:31–33). In that image

only the head representing Babylon was made of gold. Therefore, the king had

a statue built covered entirely in gold so as to negate the earlier message

of a temporary Babylonian Empire. Since a size of 90 feet high and nine feet

wide (the equivalent dimensions of a height of sixty cubits and

a width of six cubits) would make a grotesque distortion of a

human body, it is more likely this was an image placed on a large pedestal.

The location of the statue was on the plain

of Dura, a site that has not been conclusively identified. It was not in

the city of Babylon but on a plain somewhere in the province. Perhaps Daniel

was not involved in the events here since he remained in the capital city

"at the king’s court" (2:49) while other officials, including his three

friends Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-nego, were called to Dura to show their

loyalty. No doubt, had Daniel been there, he too would have refused to bow

to the image.

3:2–3. Nebuchadnezzar … sent word to

assemble all the officials of the realm to come to the dedication of

the image. Seven offices are mentioned specifically, but the exact

meaning of each position is unclear other than that they are listed in

descending order of rank. The use of the Persian loanword for satraps

does not necessarily imply an anachronism since Persian inscriptions have

been discovered from the neo-Babylonian era. Moreover, by the time Daniel

completed this book, the Persian period had already begun so it would not be

surprising for him to use Persian words.

3:4–5. Upon hearing the music, all present

were to fall down and worship the golden image. Six specific

instruments are mentioned, three of which (lyre, psaltery, and

bagpipe) are the only Greek loanwords in Daniel. This also should not

imply a date for Daniel in the later Greek period because even Assyrian

inscriptions, predating the Babylonian period, refer to Greek instruments

and musicians (Gleason Archer, "Daniel," EBC, edited by Frank E. Gabelein

[Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1985], 21).

Although some conjecture that the image was of

Nebuchadnezzar himself, this is unlikely because the Babylonians did not

believe their king was divine. More likely, the image was of a Babylonian

god, perhaps Nebuchadnezzar’s patron Nabu or the chief Babylonian god

Marduk. Despite ancient paganism tending to tolerate a panoply of gods, here

Nebuchadnezzar made this demand for worship of his god as a form of a

loyalty oath to him personally.

3:6–7. Those failing to worship the image

would be incinerated in a furnace of blazing fire, a punishment that

Nebuchadnezzar had also used on two Judean false prophets, Zedekiah and Ahab

(Jr 29:22). This was a normal Babylonian penalty as seen in the Code of

Hammurabi, Sections 25, 110 and 157. Perhaps this furnace was built to smelt

the gold for the image Nebuchadnezzar had made. The king’s threat was

sufficient to make all the officials present there, except the three Jewish

young men, worship the golden image.

2. The Young Men’s Refusal to Worship the

Statue (3:8–23)

3:8–12. When Shadrach, Meshach, and

Abed-nego refused to worship the false god, certain Chaldeans

maliciously brought charges to the king. The word Chaldeans is

both a general ethnic term for the Babylonian people and a specific term for

priests who served as astrologers, soothsayers, and wise men in the king’s

government. It is used in the secondary sense here, referring to the king’s

astrologers and wise men. Likely these were the governmental officials who

had been summoned to the plain of Dura.

Their motive in denouncing the three faithful

Jewish men was not devotion to the king’s demand but a hatred for the Jewish

people. They sought to accuse the Jews (3:8) and they referred to

certain Jews whom you have appointed (3:12). Were it not hatred for

God’s chosen people, their accusation would have been about some royal

officials without mention of their ethnicity. Hatred of the Jewish people

has been a persistent sin in the Bible from Pharaoh to Haman. It reflects a

hatred of the God of Israel and is expressed through oppression and even

attempts at genocide of His people (Ps 83:2–5). By saying that these Jewish

men did not serve your gods or worship the golden image, the wise men

were accusing them of disloyalty, another anti-Jewish slur, which persists

to this day.

3:13–18. The enraged king offered Daniel’s

friends a second chance to worship the idol, but they persistently refused.

They were confident that the true God was able to deliver them

from the furnace of blazing fire. The Aramaic imperfect verb yesezib

("He can deliver, rescue") in this context indicates possibility and not

certainty. They were saying that God may deliver them or He may choose not

to rescue. It was His choice. Their faith was not limited to belief in a

miracle but also included trust in God’s sovereignty. They asserted that if

God chose not to deliver them from this punishment but would allow them to

become martyrs for Him, they would still refuse to serve the king’s gods

or worship the golden image. This is one of the strongest statements of

faith in the entire Bible. They trusted the Lord to decide their destiny

while still being faithful to Him.

3:19–23. The infuriated king gave orders

to heat the furnace seven times more than it was usually heated, an

idiom for "as hot as possible." When the appointed guards cast Shadrach,

Meshach and Abed-nego into the furnace, the heat was so intense that its

flames slew those men who carried God’s three faithful servants to

the furnace. This indicates that there was no naturalistic explanation for

the survival of the three.

The ancient furnace was shaped like an

old-fashioned milk bottle and built on a small hill or mound with openings

at the top and side. The ore to be smelted would be dropped in a large

opening at the top and wood or charcoal would be inserted in a smaller hole

on the side, at ground level, to heat the furnace. There would have been two

other small holes at ground level in which to insert pipes connected to a

large bellows to raise the temperature of the fire. (Archer, "Daniel," 56).

Some have estimated that this furnace could reach a temperature of 1,800

degrees fahrenheit (Miller, Daniel, 115, 122). Most likely this

furnace was used to smelt the gold ore and bricks for Nebuchadnezzar’s

statue. Thus, the three men fell into the midst of the furnace (3:23)

from the top and the king was able to see into the furnace (3:24–25) from

its side opening.

3. The Lord’s Deliverance from the Fiery

Furnace (3:24–27)

3:24–25. When the king looked into the

furnace, he was astounded to see four men … walking about

in the furnace, and the fourth looked like a son of the gods.

This may have been an angel or even more likely, the Angel of the Lord,

meaning a pre-incarnate appearance of the Messiah. Nevertheless, it is

doubtful that a pagan king would have understood this. Rather, his statement

is indicative of the glorious appearance of the deliverer whom he saw. The

faithful reader is to understand who was in the furnace even though the

pagan king did not.

3:26–27. Having called the men out of the

furnace, Nebuchadnezzar and all his government officials saw that the

fire had no effect on their bodies. Not only did the fire fail to

burn their hair and clothing, they did not even have the smell of fire

on them. Hebrews 11:34 cites this miracle of faith, referring to those who

"quenched the power of fire."

4. The King’s Recognition of the God of

Israel (3:28–30)

3:28–30. King Nebuchadnezzar continued on

his odyssey of faith, begun in Dn 2. There he learned that the Lord is a

true God, powerful enough to reveal secret dreams and to control the

destinies of nations. In a sense, he recognized the God of Israel as a part

of the panoply of gods. However, in Dn 3, Nebuchadnezzar learned that

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego were "servants of the Most High God"

(3:26), indicating that he saw the God of Israel as the one who is greater

than all other gods. Even so, he remained a polytheist, believing in many

gods. Despite Nebuchadnezzar’s praise of the God of Shadrach, Meshach and

Abed-nego for His deliverance and the king’s prohibition against saying

anything offensive against the God of Israel (3:28–29), he still had

not come to a full knowledge of the one and only true God.

The three young men remained faithful to the

true God despite intense pressure to acquiesce to idolatry. They experienced

the promise of Is 43:2: "When you walk through the fire, you will not be

scorched, nor will the flame burn you." Thus, they became a model to the

faithful remnant of Israel in the times of the Gentiles as well as to any

person today who has become a follower of the Lord Jesus. Despite living in

a pressure-packed society that consistently invites disloyalty to the Lord,

His followers can be assured of His presence in the midst of the fire. God

is fully capable of supernatural deliverance from the intense heat of

pressure or to bring His faithful ones safely home to Him.

C. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride, Madness, and

Repentance (4:1–37)

1. The Prologue: A Declaration of Praise

(4:1–3)

4:1–3. The text does not indicate when the

events of Dn 4 took place nor is it significant to the interpretation of the

passage. Nevertheless, King Nebuchadnezzar most likely had his dream (see v.

5) about ten years before the end of his 43-year reign. Then, God in His

grace allowed the king one year to repent followed by seven years of

madness. Once he came to his senses, the king lived approximately two to

three years before dying in 562 BC.

Daniel has included this chapter as a formal

letter sent by Nebuchadnezzar himself to his empire. No doubt, the king did

indeed write the letter, but it is Daniel, as author of the book, who chose

to include it. It would be unlikely that the king would switch from writing

about himself in the first person (4:1–27, 34–37). Yet Daniel, as the author

of the book and personal confidante of the king, was uniquely aware of the

king’s experience. Therefore, he most likely wrote the section that speaks

of the king in the third person (vv. 28–33) and records his time of mental

illness. The chapter is structured in three sections: (1) a prologue

in which the king praises the true God (4:1–3); (2) a narrative body

(4:4–34a), which recounts (a) the king’s dream, (b) Daniel’s interpretation,

(c) the king’s illness and repentance; and (3) an epilogue in which

the king declares his own recognition of the sovereignty of the true God

(4:34b–37). Of course, the chapter is written from the perspective of the

king looking back at the signs and wonders which the Most High God

had done for him (4:2). Therefore, this prologue reflects what the king had

already come to understand by the end of the chapter—that God’s kingdom

is an everlasting kingdom and His dominion is from generation to generation.

2. The Story: A Dream Comes to Pass

(4:4–34a)

4:4–34a. The story covers a period of eight

years, beginning with the dream, the year afterward, and then the seven-year

period of mental illness.

a. The King’s Dream (4:4–18)

4:4–7. King Nebuchadnezzar once again had

recurring dreams that alarmed him. Therefore, he called the four classes of

wise men to interpret his dream (for the meaning of magicians and

conjurers, see the comments at 1:20–21, for Chaldeans see 2:2–3

and for diviners see 2:27). Unlike the dream of Dn 2, the king

related the dream to them but similarly they could not make its

interpretation known to him.

4:8. Daniel finally came before the

king—perhaps he was away from the palace when the previous wise men appeared

before the king or maybe he was only brought to deal with problems beyond

the ability of the ordinary wise men. No matter, the king recognized that

a spirit of the holy gods was in Daniel. This translation reflects the

perspective of a pagan king but since the king is relating this from the

perspective of a chastened king who knows that God alone can reveal what is

hidden, it might be better to translate the phrase "the spirit of the Holy

God is in him."

Beginning in this verse and throughout the

chapter, Daniel is most frequently called by his Babylonian name

Belteshazzar, likely because it was written from the perspective of the

Babylonian king, not a Hebrew exile.

4:9–13. Nebuchadnezzar related his dream to

Daniel, describing what he saw as a tree … great and which

grew large and became strong And its height reached to the sky, a figure

for an exceptionally tall tree. A similar expression was used in Gn 11:4 for

the tower of the city of Babylon, the top of which was to reach "into

heaven." The tree provided food and shelter for all the creatures

of the earth. The king also saw an angel, here called a watcher, a holy

one.

4:14–18. The angel in the king’s dream

announced that the tree would be cut down but that the stump with its

roots would remain in the ground, indicating the continuation of

life. The stump was to have a band of iron and bronze around it,

indicating the protection of the stump. The tree plainly represents a man

(the king) because the angel declared that his mind would be

changed from that of a man to that of a beast’s for seven

periods of time or for seven years.

b. Daniel’s Interpretation (4:19–27)

4:19. Daniel was appalled for a while

and his thoughts alarmed him upon hearing the dream because he

understood its meaning. As a loyal servant of the king, Daniel was alarmed

about the dreadful discipline that would befall the king.

4:20–26. The tree represented King

Nebuchadnezzar who would be given a mental illness that would cause him to

live outdoors like the beasts of the field and feed on grass …

like cattle for seven years. This would last until King

Nebuchadnezzar repented of his pride and recognize[d] that the Most High

is ruler over the realm of mankind and bestows it on whomever He wishes.

Rather than taking credit for his own accomplishments, the king needed to

recognize God’s sovereignty in placing him in his position. When the king

would acknowledge that it is Heaven that rules, God would restore his

sanity and realm to him. This is the only place in the OT where Heaven

is a metonymy for God. This usage became commonplace in intertestamental

literature, the NT, and Rabbinic literature.

4:27. Daniel advised the king to repent

with the hope that this might stay God’s discipline. To do so, the king was

to separate himself from his sins by doing righteousness. Some have

understood the Aramaic word for "righteousness" as a reference to giving

charity. In post-biblical Hebrew and Aramaic this word does indeed begin to

include "giving charity" within its range of meaning. However, this use in

the book of Daniel would be too early for that definition and would merely

mean "justice." Rather than calling for good deeds as a means of salvation

or even of staying temporal judgment, Daniel exhorted the king to

acknowledge God’s rulership by faith, and having done so, to break

with his sins and live in conformity to God’s righteous (or just)

standard.

c. The Dream’s Fulfillment (4:28–34a)

4:28–30. One year later, Daniel’s

predictions were fulfilled. Nebuchadnezzar, who had no fewer than three

palaces in the city of Babylon, was walking on the roof of one of

them. Seeing the magnificent city, he was overcome with its grandeur and

became consumed with pride. He called the city Babylon the great, a

phrase echoed in Rv 17:5 and 18:2.

According to Herodotus (a Greek historian who

died c. 425 BC), Babylon was the most glorious city of the ancient world. He

recorded that Babylon’s outer walls alone were 56 miles long, 80 feet wide

and 320 feet high. Nebuchadnezzar was a great builder and expanded the city

to six square miles. He also beautified it with magnificent buildings,

temples, and palaces. Within the city there were some 53 temples to various

gods, many containing massive gold statues. The main sacred procession

street passed from the famed Ishtar Gate to the Temple of Marduk, with its

adjacent ziggurat rising 288 feet into the sky. A 400-foot bridge

spanned the Euphrates River and united the eastern and western halves of the

city. On the northwest corner of the king’s primary palace sat one of the

Seven Wonders of the World, the famed Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Built on

terraces, it more properly should be called overhanging gardens. Whether the

ancient historian exaggerated or gave a precise depiction, the city of

Babylon was indeed the largest, most populated, and greatest city in the

known world at that time. Perhaps it was on the roof of the Hanging Gardens

with a view of his glorious city that Nebuchadnezzar became filled with

pride.

The king’s overwhelming pride is evident in his

exclamation: Is this not Babylon the great, which I myself have

built … by the might of my power and for the glory of my

majesty? (italics added, v. 30). Note Nebuchadnezzar’s emphasis on

himself and his failure to give God the credit and the glory for giving all

of this to him. Many years later, Paul would upbraid the Corinthians for

their pride by asking, "What do you have that you did not receive? And if

you did receive it, why do you boast as if you had not received it?" (1Co

4:7). Herein lies the problem with pride: it takes credit for what God alone

has done.

4:31. After a year of patience (4:28), God

enacted His discipline at the very instant that Nebuchadnezzar had become

fully consumed with his pride, even while the word was in the king’s

mouth. As evidence that God alone is the source of human accomplishment

and authority, Nebuchadnezzar’s sovereignty was taken away and the

king descended into the abyss of mental illness.

4:32–33. Nebuchadnezzar was driven to live

with the beasts of the field, apparently suffering from boanthropy, a

rare mental illness in which people believe they actually are cattle. Hence,

he began eating grass like cattle, and his body was drenched with the dew.

One modern case of boanthropy resulted in the patient growing long matted

hair and thickened fingernails, much like Nebuchadnezzar, whose hair grew

like eagles’ feathers and his nails like birds’ claws (Harrison,

Introduction to the Old Testament, 1116–17).

Critics contend that secular history has no

record of Nebuchadnezzar’s mental illness, thereby challenging the

historicity of this account. However, it is questionable as to whether an

ancient Near Eastern despot would place his bout with insanity into official

court records. Moreover, Eusebius, the church historian (d. AD 339), citing

Abydenus, a third-century BC Greek historian, referred to a time, late in

Nebuchadnezzar’s life when he was "possessed by a god" (Praeparatio

Evangelica IX, 41, cited by Leon Wood, A Commentary on Daniel [Grand

Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1973], 121–22), a possible secular reference to the

events of Dn 4. Also, third-century BC historian Berosus possibly referred

to these events when he spoke of an illness that befell Nebuchadnezzar just

prior to his death (Wood, Daniel, 122).

Critics have questioned whether the Babylonian

Empire could function while mental illness incapacitated its king. Yet,

excellent administrative leadership, such as provided by Daniel, would

certainly have kept the kingdom intact.

4:34a. The nature of boanthropy is not such

that the sufferer cannot reason or understand what has befallen him. So, it

was possible for the king to realize that his own pride had caused his

insanity and therefore, repent. Hence, when Nebuchadnezzar raised his

eyes toward heaven in repentance for his pride and acknowledged the

Most High God, his sanity returned to him fully and instantly.

3. The Epilogue: A Declaration of

Sovereignty (4:34b–37)

4:34b–35. As an epilogue to the narrative,

Nebuchadnezzar glorified God, using words that describe not only his own

realization but summarize the theme of the book of Daniel: He recognized

God’s everlasting dominion, His eternal kingdom, and His

sovereignty over all the inhabitants of the earth.

4:36–37. Having repented, Nebuchadnezzar

finds his sanity returned, and the Lord also restored his majesty and

sovereignty over Babylon. The very last sentence of the chapter

summarizes the message of this story: God is able to humble those who

walk in pride. Although some have disputed that the pagan King

Nebuchadnezzar actually did come to a saving knowledge of the true God, it

appears that he did. In his 40-year journey of faith, Nebuchadnezzar

accepted the God of Israel into the panoply of gods (2:47), recognized

Israel’s God as the Most High God (3:26), and ultimately repented of his

pride and submitted to the God of Israel’s sovereignty over the world and

his own life (4:34–37). Therefore, near the end of his life, Nebuchadnezzar

experienced salvation when he came to know and follow the God of Israel.

Too often, people take credit for their own

skills, status, or success. It would be wise to learn the lesson of

Nebuchadnezzar and acknowledge that all these come from the Sovereign of the

universe, not ourselves.

D. Belshazzar’s Feast and the Writing on

the Wall (5:1–31)

The developments in Dn 5 took place some 23

years after the events in the previous chapter. Nebuchadnezzar had died in

562 BC, shortly after his time of insanity and subsequent repentance. After

his death, a series of intrigues and assassinations resulted in several

obscure kings ruling Babylon until Nabonidus took the throne (556–539 BC).

Earlier critics questioned the historicity of Belshazzar, since he

was unknown in secular documents. However, beginning in 1914, 37 separate

archival texts have been discovered, documenting the existence of Belshazzar

as crown prince. Discovered ancient texts also confirm that Nabonidus spent

much of his reign in Arabia, leaving Belshazzar in Babylon, to rule the

empire as coregent.

1. The Feast of the King (5:1–4)

5:1. Belshazzar the king held a great feast for

a thousand of his nobles most likely to bolster the morale of the

nobility after Nabonidus had experienced a crushing defeat at the hands of

the Persians. Ancient Greek historians Herodotus and Xenophon confirm that

Babylon fell while a great feast was in progress (5:30). Excavations in

Babylon have uncovered a large throne room that could have easily

accommodated one thousand nobles.

5:2–4. While feasting, Belshazzar gave

orders to bring the gold and silver vessels which had been taken out

of the temple 47 years earlier. By drinking libations to Babylonian gods

with vessels devoted to the true God of Israel, Belshazzar was acting in an

unusually aggressive and blasphemous way. Nebuchadnezzar was called

Belshazzar’s father, even though Nabonidus was his father. Most

likely, Belshazzar’s father, Nabonidus, married Nebuchadnezzar’s daughter to

establish his own claim to the throne of Babylon, making Nebuchadnezzar the

grandfather of Belshazzar. The Aramaic word translated "father" could refer

to a grandfather, ancestor, or even a predecessor to a king without any

lineal tie whatsoever.

2. The Writing on the Wall (5:5–9)

5:5. It was precisely at that moment, when

the king and his nobles were mocking the God of Israel, that the fingers

of a man’s hand emerged and began writing … on the plaster of the

wall. This was not a vision merely seen by Belshazzar alone but a

miracle seen by all present. Even afterward, the wise men called to

interpret could still see the words written on the plaster wall. According

to the archaeologist who excavated Babylon, the Babylonian throne room (see

5:1) had walls covered with white gypsum (or plaster), fitting the

description contained in Daniel (cf. Robert Koldeway, The Excavations at

Babylon, [London: Macmillan, 1914], 104).

5:6–7. The writing on the wall so terrified

Belshazzar that his hip joints went slack and his knees began knocking

together. Therefore, he called for the wise men and offered great

honor if any of them could interpret the words on the wall. He even proposed

to make the successful wise man third ruler in the kingdom, after

Nabonidus and Belshazzar.

5:8–9. None of the wise men could

read the inscription or make known its interpretation, following the

pattern of the book (cf. 2:3–13, 4:7). Consistently, the wise men of Babylon

were incapable of interpreting God’s messages—only Daniel, God’s prophet,

was capable of doing so (1:17).

3. The Advice of the Queen (5:10–12)

5:10. The queen who entered the banquet

hall was the Queen Mother, not the wife of King Belshazzar since all his

wives were already present with him (cf. 5:3).

5:11–12. Daniel was approximately 80 years

old at this point and was either retired or forgotten. The Queen Mother, who

was the daughter of Nebuchadnezzar, remembered Daniel’s extraordinary

spirit and his abilities to interpret dreams, explain enigmas,

and solve difficult problems during her father’s reign. Therefore,

she advised her son to call Daniel to declare the interpretation of

the writing on the wall.

4. The Meeting with Daniel (5:13–29)

When Daniel was brought before the king, he did

not demonstrate the same level of respect that he had consistently shown to

Nebuchadnezzar. Instead, he rebuked Belshazzar for his brazen attitude and

failure to learn from Nebuchadnezzar. Rather than remembering the lesson of

humility before the God of Israel that his father had learned, Belshazzar

had brazenly mocked the true God.

5:13–17. Upon hearing the king’s offer to

honor him and make him the third ruler in the kingdom, Daniel refused

to accept any gift, telling the king to give his rewards to

someone else. This was not because Daniel was rude or arrogant but

rather indignant at the king’s disregard for Nebuchadnezzar’s lesson of

humility before God and his blasphemous use of the temple vessels.

5:18–24. Writers of historical narrative

frequently communicate the essential message of a text through dialogue. In

this case, Daniel’s words served as a rebuke for Belshazzar for his failure

to learn from the experience of Nebuchadnezzar (as described in Dn 4).

Daniel reviewed for Belshazzar that the Most High God had granted

sovereignty to Nebuchadnezzar, Belshazzar’s predecessor. Also,

that God had humbled Nebuchadnezzar when his spirit became … proud

by afflicting him with boanthropy until he recognized the sovereignty

of the God of Israel. Daniel reprimanded Belshazzar because he had not

humbled his heart, even though he knew all this. According

to ancient Babylonian texts, Belshazzar had served in the government of King

Neriglissar (who ruled Babylon from 560–556 BC) in 560 BC indicating that he

had been old enough to be aware of the events at the end of Nebuchadnezzar’s

life. Instead of learning to submit to the Almighty, he used the temple

vessels to blaspheme God and so exalted himself against the Lord

of heaven. The specific sins Daniel cited were pride, blasphemy,

idolatry, and failure to glorify the true God. For this reason, the

inscription was written on the wall with a message of judgment and doom.

5:25–29. The three words on the wall were

Aramaic as follows: MENE (numbered), TEKEL (weighed) and

UPHARSIN (divided). They indicated that Belshazzar’s days were numbered

and his kingdom would come to an end, that his reign had been weighed and

found deficient, and that Babylon would be divided among the

Medes and Persians.

Although the third word was written on the wall

in the plural form (UPHARSIN), Daniel explained its meaning by using

the singular form (PERES). The prediction that Belshazzar’s

kingdom has been divided does not indicate that the Babylonian Empire

would be divided equally by two kingdoms (Medes and Persians) but

rather that Babylon would be destroyed or dissolved and taken over by the

Medo-Persian Empire. The third word on the wall (UPHARSIN) has the

same letters as the Aramaic word for "Persian," and was used as a play on

words, indicating that the kingdom would fall to a Persian army.

5. The Fall of Babylon (5:30–31)

5:30. Having lost a brief skirmish outside

the walls of Babylon, Belshazzar had retreated to the city and made light of

the coming Persian siege. The Babylonians had 20 years of provisions, and

the city was a seemingly impregnable fortress. Nevertheless, Darius diverted

the waters of the Euphrates and entered below the water gates. He took the

city that same night without a battle and killed Belshazzar. Xenophon

noted that the city fell while the Babylonians were in the midst of a

drunken feast. The kingdom of Babylon fell just as foretold by Daniel in his

interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of the statue (2:39). The head of

gold (Babylon) had fallen and was replaced by the chest and arms of silver

(Medo-Persia) (2:40).

5:31. The identity of Darius the Mede

who received the kingdom at about the age of sixty-two is uncertain.

Some believe that he was Gubaru, the governor of Babylon (cf. J. C.

Whitcomb, Jr., Darius the Mede [Grand Rapids, MI: BAker, 1959]). and

called Darius because it was not a personal name but an honorific

title, meaning "royal one" (Archer, "Daniel," 76–77). Others maintain that

Darius the Mede was an alternate title for the Persian emperor, Cyrus

the Great, also viewing the word Darius not as a name but as a royal

title (J. M. Bulman, "The Identification of Darius the Mede," WTJ 35

[1973]: 247–67). Both of these identifications are possible, but there is no

conclusive evidence for either. Regardless, Darius the Mede was not a

fictional character but an actual historical figure.

God did not intend for Nebuchadnezzar alone to

learn to honor the true Lord of heaven (cf. Dn 4:37). He also expected

Nebuchadnezzar’s descendants to glorify Him as well. Unlike Belshazzar, who

ignored the humbling of his predecessor, followers of Messiah today must

learn the lesson of humility, exalting the Lord above all in their lives and

recognizing His granting of every good gift.

E. Daniel in the Lions’ Den (6:1–28)

In one of the most well-known stories in the

book, Daniel was cast into the lion’s den for his faith. Since Daniel was

about 15 in 605 BC, when the Babylonians brought him as a captive to

Babylon, and since the events in Dn 6 most likely took place in the second

or third year after the Medo-Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, Daniel

would have been approximately 82 years old when he was cast into the lions’

den (see the chart, after the comments on 6:28, on Daniel’s age throughout

the events in the book). He was an old man, not a teenager, as is often

pictured in Bible storybooks and sermons.

1. The Plot against Daniel (6:1–9)

6:1. Darius began organizing the newly

conquered Babylonian Empire and immediately decided to appoint 120

satraps over the kingdom. According to Herodotus, there were 20

satrapies in the Medo-Persian Empire (3.89–94), while the book of Esther

records that the Persian Empire had 127 provinces (Est 1:1; 8:9). It can be

assumed that the 120 satraps identified here are not to be understood

as one satrap for each particular section of the entire empire, but rather

lower officials who helped rule over the entire empire or just over that

part of the empire that was formerly Babylonian.

6:2. The king appointed three

commissioners over the 120 satraps, to assure that the 120 government

officials would properly collect taxes without any embezzlement or

corruption. For the three administrative leaders, the king needed men with

trustworthy reputations and so chose Daniel as one. He must have

heard of Daniel’s reputation or perhaps he may have been aware of Daniel’s

interpretation of the writing on the wall on the night Babylon fell.

6:3. Quickly, Daniel began

distinguishing himself as a superlative administrator because of his

extraordinary spirit, a phrase previously used to describe him (5:12).

Therefore, the king planned to appoint him over the entire kingdom as

prime minister.

6:4–5. The king’s choice of Daniel created

jealousy in the other court officials and they wished to denounce Daniel.

Since Daniel was both diligent and honest in his work, the commissioners

and satraps could not find any negligence or corruption … in

him. Therefore, they sought to create a law sure to contradict Daniel’s

faith in order to entrap him.

6:6–7. When these corrupt officials

approached the king, they falsely claimed that all government

officials supported the proposal that for 30 days anyone who makes a

petition to any god or man besides the king would be cast into

the lions’ den. By agreeing to this law, Darius had not claimed deity

but rather adopted the role of a priestly mediator. His goal was to unite

the Babylonian realm under the authority of the new Persian Empire.

6:8–9. The irrevocability of the law of

the Medes and Persians is confirmed elsewhere in Scripture (Est 1:19;

8:8) and secular literature (Diodorus of Sicily, XVII:30).

2. The Prosecution of Daniel (6:10–14)

6:10–11. Even though the law prohibiting

prayer had gone into effect, Daniel still prayed with his windows open

toward Jerusalem. Jewish people in exile always pray toward

Jerusalem—even today—just as Solomon had directed in his prayer of

dedication for the temple (1Kg 8:44–49). Daniel prayed three times a day

either because this was his own personal devotional habit or perhaps because

the Jewish custom of morning, afternoon, and evening prayers had already

been established. Daniel prayed not out of rebellion to the king but out of

obedience to the greater command of God. As the apostles would later say,

"We must obey God rather than men" (Ac 5:29). So great was Daniel’s