DEUTERONOMY

James Coakley

INTRODUCTION

The English title for the fifth book of Moses comes from the Greek Septuagint (LXX) name Deuteronomion, meaning "second law." The LXX derived this from the phrase "copy of this law" from Dt 17:18, erroneously understanding the book as a repetition of the book of Exodus. The Jewish title for the book is elleh haddebarim, the first Hebrew words of the book, meaning "these are the words." This is a more accurate reflection of Deuteronomy since the bulk of it consists of the speeches Moses gave to the nation Israel just before they entered the promised land. Also, this title reflects the sermonic element of this material, rather than focusing on the legislative quality of the book.

Author. Internally the book is clearly attributed to the hand of Moses (31:9, 24), and there are several references to Moses "speaking" the content of this book (1:9; 5:1; 29:2; 31:30). No other OT book is as clearly attributed to a human author as this one, so to suggest otherwise means that the burden of proof clearly lies with those do not hold to a Mosaic authorship of the book. Some editorial additions have been inserted (e.g., 34:5–12), but the core of this book is attributed to Mosaic composition as Joshua (Jos 1:7–8), Ezra (Ezr 3:2), and Jesus Himself attest (Jn 5:45–47). For most critics of the Pentateuch, Deuteronomy is the "D" portion of the JEDP documentary hypothesis identified with the "book of the law" found in the temple in 2Kg 22:8–11 and is a unified whole edited by a single writer who lived in the seventh century BC. For a critique of the documentary hypothesis see the Introduction to the book of Genesis.

Date. The historical background of the book is the period of the nation Israel just before they crossed the Jordan River into the promised land (c. 1405 BC).

Covenantal in form, this book resembles the format of ancient Near Eastern treaties, specifically the suzerain-vassal treaty texts as advanced by Meredith Kline (Treaty of the Great King: The Covenant Structure of Deuteronomy: Studies and Commentary [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1963]), but the overall style and genre of Deuteronomy is hortatory and homiletical. Moses was exhorting the readers/listeners to certain behavior by using motivation clauses and directives. While the book does include some laws, it is not entirely a book of laws since it also contains narrative and poetry. In addition, while it does use treaty language, the word "covenant" (Hb. berith) is not used in the book to describe its overall nature. It is best to view the book, as Olson does (D. T. Olson, Deuteronomy and the Death of Moses, [Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1994], 10–12), mainly as a catechetical type book that distills the essential traditions and theology of Israel. The book includes the core of the faith-based education that was to be passed down from generation to generation. Deuteronomy is the closest that the OT comes to a systematic theology. Deuteronomy should not be viewed as a self-standing, independent book but as one part of a unified book, the Torah, which includes all five books of the Pentateuch.

Theme and Purpose. Since it is primarily a teaching book, its purpose is to call Israel to covenant loyalty and obedience. Each subsequent generation of readers is, as it were, on the plains of Moab being reminded to love the Lord wholeheartedly and not to forget the God who graciously fulfills promises and longs for a personal relationship with His children. Israel was to prepare to claim God’s promises by being rooted in God’s Word and by abounding in love for Him and others.

Structure. Deuteronomy has three overlapping structures:

First it mirrors the form of ancient Near Eastern treaties, which highlights the book’s covenantal emphasis:

I. Preamble (1:1–5)

II. Historical Prologue: Covenant History (1:6–4:49)

III. Stipulations (5–26)

IV. Blessings and Cursings (27–30)

V. Witnesses (30:19; 31:19; 32:1–43)

Second, Deuteronomy is also organized in a chiastic structure, which pivots on the central body of legislation in chaps. 12–26.

A Historical Look Backward (chaps. 1–3)

B Exhortation to Keep the Covenant (chaps. 4–11)

C The Center: The Stipulations of the Covenant (chaps. 12–26)

B’ Ceremony to Memorialize the Covenant (chaps. 27–30)

A’ Prophetic Look Forward (chaps. 31–34)

Third, various superscriptions are used to introduce the different portions of the book, which serves the book’s internal organization as a teaching book:

1:1. "These are the words"—

The Past (chaps. 1–4)

4:44. "This is the law"—

The Ten Commandments (chap. 5)

6:1. "This is the commandment, the statues and the judgments"—

Laws for the Present (chaps. 6–28)

29:1. "These are the words of the covenant"—

The Future Covenant Renewal (chaps. 29–32)

33:1. "This is the blessing"—

Blessing for the Future (chaps. 33–34)

Background. The presence and influence of Deuteronomy is evident throughout the Bible. It provides orientation for what happens in the rest of the OT and even influences the NT. Seven facts may be noted in this connection.

First, Deuteronomy explains the success of Joshua and the failure of the period of the judges. To have success, Joshua was instructed (Jos 1:8) to meditate and keep "this book of the law" (i.e., Deuteronomy). Joshua faithfully executed the teaching of this book, even to the point of conducting a covenant renewal ceremony at the end of his life. He certainly impressed the Word on his children, because at the end of his life he boldly proclaimed, "As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord" (Jos 24:15). Joshua was successful because he knew and lived Deuteronomy. The complete opposite happened in the period of the judges. It was a chaotic period, full of flawed leaders when "everyone did what was right in his own eyes" (Jdg 21:25). In that time period Israel was not doing what was right according to "the book of the law," and so it experienced failure.

Second, Deuteronomy explains the success and failure of the Israelite kings (Dt 17:14–20). Each king was to handwrite his own personal copy of the "book of the law" (a phrase which might refer only to Deuteronomy since it is the only book in the Torah to use it (29:21; 30:10; 31:26]). That way he could not feign ignorance of God’s commands. King David most likely followed this injunction (Ps 1, 19, 119), whereas his son Solomon did not (cf. Dt 17:16–17 with 1Kg 10–11). Jeroboam clearly violated the commands of Deuteronomy in 1Kg 12, and this was later true of other evil kings (1Kg 15:34; 16:26).

Third, Deuteronomy explains the existence of many prophets in the eighth to sixth centuries BC. Israel’s spiritual decline caused God in His grace to send prophets, who in essence said: "Read and heed Deuteronomy." The nation needed to hear the message that if they listened and lived by Deuteronomy God would bless them and forestall His judgment against them. If they responded correctly, they would receive the blessings of Dt 28, and if not they would reap the curses of Dt 28. In essence the prophets’ repeated message was the book of Deuteronomy. All the prophets, especially Hosea, Jeremiah, and Daniel, all beat with the same heartbeat of Deuteronomy. For readers to understand the prophets they must understand the message of Deuteronomy.

Fourth, Deuteronomy explains the reason for the Babylonian exile (Dt 28:36): "The Lord will bring you and your king, whom you set over you, to a nation which neither you nor your fathers have known, and there you shall serve other gods, [gods of] wood and stone." In summary the exile of 586 BC happened because no one heeded Deuteronomy.

Fifth, Deuteronomy greatly influenced the NT. Deuteronomy is one of the four books most frequently quoted in the NT (Psalms, Genesis, and Isaiah are the others). Paul’s epistles are loaded with quotations from and allusions to this book.

Sixth, Deuteronomy was an integral part of the "Bible" Jesus read and lived. Jesus astounded the teachers at the temple with His knowledge of the law at the age of 12 (Lk 2:46–47). After He was baptized, He was driven by the Spirit into the Judean wilderness to be tempted by the devil, where in Mt 4 (vv. 4, 7, 10) He quoted three times from Deuteronomy. The first Adam fell to temptation in a garden by doubting God’s Word, and the Last Adam resisted temptation in a desert by reciting what God said in Deuteronomy. This shows that Jesus is the ideal perfect King, for He "knows" Deuteronomy (cf. Dt 17:18–20).

Seventh, Deuteronomy summarizes the first great commandment. When Jesus was asked "Which is the great commandment in the Law?" He replied: "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind" (Mt 22:36–37; Dt 6:5). Deuteronomy is the first book in the OT to command believers to love God, and it mentions this repeatedly. "Love the Lord your God" (Dt 11:1; 30:16).

OUTLINE

I. Introduction (1:1–5)

II. Moses’ First Address: Historical Prologue (1:6–4:43)

A. Historical Review of God’s Gracious Acts from Horeb and Beth Peor (1:6–3:29)

B. An Exhortation to Obey the Law Faithfully (4:1–40)

C. Additional Cities of Refuge (4:41–43)

III. Moses’ Second Address: The Stipulations (4:44–26:19)

A. The Essence of the Law and Its Fulfillment (4:44–11:23)

B. Exposition of Selected Covenant Laws (12:1–25:19)

C. Ceremonial Fulfillment of the Law (26:1–19)

IV. Moses’ Third Address: Blessings and Curses (27:1–28:68)

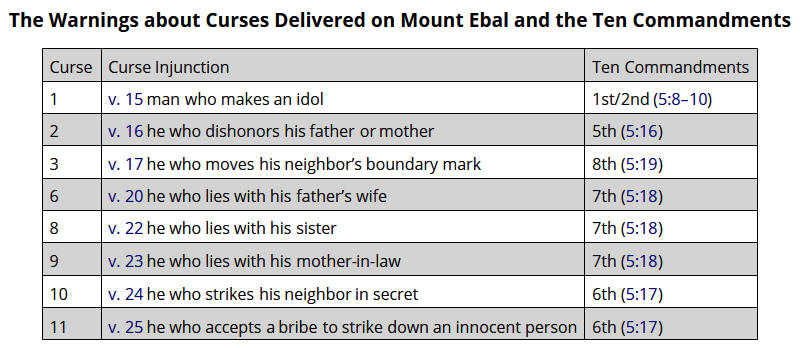

A. Renewal of the Covenant Commanded (27:1–26)

B. Blessings and Curses (28:1–68)

V. Moses’ Fourth Address: Exhortation to Obedience (29:1–30:20)

A. An Appeal for Covenant Faithfulness (29:1–29)

B. The Call to Decision: Life and Blessing or Death and Cursing (30:1–20)

VI. Conclusion (31:1–34:12)

A. Deposition of the Law and the Appointment of Joshua (31:1–29)

B. Song of Moses (31:30–32:43)

C. Preparation for Moses’ Death (32:44–52)

D. The Blessing of Moses on the Tribes (33:1–29)

E. Death of Moses (34:1–12)

COMMENTARY ON DEUTERONOMY

I. Introduction (1:1–5)

1:1–5. While the book of Deuteronomy takes its shape from the covenant treaty format, the opening words state that this book is a series of addresses (words) from the mouth of Moses to the entire nation of Israel located across the Jordan in the wilderness. The words all Israel often occur at key section breaks in the book (5:1; 29:2; 31:1; 32:45) and are used as bookends in the last verses of the book (1:1; 34:12). For Moses, the unity of the nation is a key element in his theology, introduced early on in the Pentateuch in the Cain and Abel account, stressing that they should be their "brother’s keeper" (Gn 4:9).

The Israelites camped in desolate surroundings in the wilderness, in the Arabah. The Arabah is the rift valley that begins in the north near the Sea of Galilee and proceeds southward to the Gulf of Aqaba. The location is further specified with geographical place names that are not easy to identify. While the bulk of the book of Deuteronomy is composed of the words of Moses, the opening verses (1:1–5) seem to be an introduction written by someone else (possibly Joshua or whoever included the epilogue at the end of Deuteronomy) residing at the time in the land of Israel (which Moses never entered). Moses spoke to Israel while they were across the Jordan in the wilderness (v. 1), which would not be the geographical point of view of Moses if he penned this exact introduction. The conclusion of Deuteronomy (chap. 34) includes information about the death of Moses, so probably another person superintended by God to write inspired text framed the book with Moses’ words in the introduction and conclusion. The book is placed both geographically and chronologically (vv. 2–3). The Israelites’ location was said to be an eleven days’ journey from Horeb, which is about 150 miles distance. Horeb is another name for Mount Sinai. Horeb is mentioned nine times in Deuteronomy and Sinai only once (33:2). The mention of "eleven days’ journey" contrasts starkly with the Israelites’ earlier movement of that same span that took 40 years. This is a clear reminder of the Israelites’ lack of faith and disobedience after God brought them out of Egypt. At this time (the 40th year) Moses spoke all that the Lord had commanded him to give to them. The historical setting is further identified as taking place after the defeat of two kings, Sihon and Og (Nm 21:21–35), and the geographical setting is repeated (Dt 1:1, 5) as being across the Jordan (v. 5).

These opening words set up the introduction of the book of Deuteronomy as given by Moses, and they also present a proper perspective for all future readers. Every generation, as it were, can be seen to be "across the Jordan," not having fully inherited the promises of God. Each subsequent generation, not just the first one, needs to be reminded of the consequences of disobedience (40 years instead of 11 days) and also of God’s grace (defeat of Sihon and Og)—and of the importance of listening to "all that the Lord commanded" by the mouth of Moses. This introduction masterfully presents the book’s historical setting, and also its theological importance, to all who read this book.

II. Moses’ First Address: Historical Prologue (1:6–4:43)

A. Historical Review of God’s Gracious Acts from Horeb and Beth Peor (1:6–3:29)

1:6–8. Moses’ first speech begins by stating that it is the Lord our God who spoke. That phrase occurs over 20 times in the book, including the Shema passage (6:4). It stresses the relational and communal aspects of the relationship the Israelites enjoyed with the Lord. In retelling the history of their journey, Moses began by quoting the Lord’s detailed instructions about the lands they were to possess. After a year at Horeb (Nm 10:11) the Lord commanded them to leave and begin to claim the land He promised to the patriarchs. By stating these specific words of the Lord first, Moses was stressing the gift of the promised land and God’s promise-keeping ability. The Israelites’ responsibility was simply to see and possess (v. 8). They merely needed to see God’s gift with their eyes and then lay hold of it.

1:9–18. While Moses was stressing God’s promise-keeping ability, he was also highlighting his own inadequacies in leading the nation alone (v. 9). As he did at God’s initial calling of him in Ex 3–4, Moses revealed his character trait of inadequacy, stating his inability to do alone what the Lord asked him to do. So he requested the aid of others to fulfill the task. Now, instead of having Aaron assisting him (Ex 4:14–16), he rehearsed how tribal leaders were selected to assist him in solving legal disputes (Ex 18:13–27). He felt he could no longer manage the growing Israelite population nor could he properly respond attitudinally to their strife (v. 12). The Israelites were increasing like the stars of heaven as a result of God’s fulfilling the Abrahamic covenant (Gn 15:5). It appeared as though the nation would only get larger, so Moses was open about his need for help to govern.

Another one of his character traits revealed early in his life was his anger (Ex 2:12). Anger is also one of the reasons he was forbidden to enter the promised land (Nm 20:10–11). So Moses in his opening words transparently revealed two of his own flaws: feelings of inadequacy and anger in the midst of strife. Even though Jethro is not mentioned here, he was the one who specifically suggested to Moses that he appoint judges to adjudicate the small cases and that Moses handle only the "hard" cases (Ex 18:14–15). The judges were to be wise and discerning, with experience and reputations above reproach. The division of the judges in ever-larger circles of authority speaks of military-like precision in the handling of personal and civil matters. These judges were to be impartial and not influenced by a person’s origin, wealth, or status.

This emphasis on justice and righteousness early in the book suggests these are key themes and purposes of the book. Of all the possible narratives about the wilderness wanderings to focus on in this opening section of Deuteronomy, Moses selected the account that stressed judges be impartial in their rendering of judgments. This is an important matter to keep in mind for whoever would seek to apply the laws found later in this book.

1:19–21. Moses continued his survey of the experiences in the exodus. After they set out from Horeb, Israel passed through the great and terrible wilderness until they arrived at Kadesh-barnea. The barrenness of the wilderness contrasted starkly with the fruitful land the Lord promised them. In such inhospitable territory God would show His faithfulness by providing for them. This land was currently under the control of the Amorites, meaning that Israel would need to uproot them if they were to possess the land. Verse 21 in essence repeats v. 8, stressing not only the gift of the land but also the importance of obediently taking possession of it without fear or discouragement of the mission now before them.

1:22–33. After arriving at Kadesh, Moses agreed to the people’s request to send men to search out the land to map out a battle strategy. So twelve representatives, one from each tribe, spied out the land. They brought back fruit as a proof of the land’s fertility, and they verbally attested to its overall goodness and suitability as a homeland. Moses did not stress the role of the ten men (Nm 13:31–33) in tainting the report. Instead he placed the blame for failure to take possession of the land on the entire nation, who rebelled against the Lord’s command. Not only did they fear the size and strength of the Amorites (by exaggerating their fortifications Dt 28), but they also questioned God’s goodness and motives, thinking that He hated them and was out to destroy them. The words the sons of the Anakim (v. 28) were used to evoke fear in those who heard them. The words are used often as the epitome of a formidable enemy (2:10, 21; 9:2; Nm 13:33). Moses sought to calm their fears by reminding them of the Lord’s presence and protection in their escape from Egypt. He also used a tender familial metaphor (as a man carries his son, v. 31) to portray God’s compassionate care for the nation while they were in the wilderness. Yet in spite of the Lord’s presence, protection, and compassion, the people failed to trust the Lord, who acted as a military scout to guide them every step of the way during their journeys in the desert.

1:34–40. In response to their rebellion and grumbling, the Lord was angry and took an oath saying that none of the men from that evil generation would see or enter the land, except for Caleb and Joshua. Even Moses was not allowed to enter the land because the Lord was angry against him for his rebellion and lack of belief (Nm 20:12). The rebellious generation feared that their children would be devoured by the inhabitants of Canaan, but it was those children who would actually inherit and possess the land. The Lord then sentenced them to turn around and head back into the wilderness.

1:41–46. Even though the people acknowledged their sin and sought to follow the Lord’s previous command to go up and fight, Moses relayed the Lord’s message, stating that they should not attempt to take the land by force or else they would be defeated. Again the people failed to obey and presumptuously attacked the Amorites in the hill country. The enemy crushed their attempt and chased them back to Hormah (most likely in the Negev; cf. Jos 15:30). The nation wept over their behavior, but the Lord did not reverse His sentence and allow them to enter the land. Instead they remained in the wilderness at Kadesh many days.

2:1–8. Even though the nation rebelled there were times of obedience as here when they set out for the wilderness … as the Lord spoke (v. 1). However, instead of heading directly to the promised land they headed south toward the Red Sea. The phrase many days (repeated from 1:46) evokes an image of futility, further heightened by the innumerable times they circled Mount Seir, located in a mountain range on the border of Edom south of the Dead Sea. The Lord addressed Moses during this wandering and gave the nation clearance to head northward, passing through the territory of the sons of Esau (Edomites). They are familially referred to as "your brothers," but the Jewish people lived in fear of them. So Israel was to not do anything to provoke them as they passed through their territory and to compensate them for any food or water they consumed. As the Lord had graciously provided for the Israelites during the 40 years in the wilderness, they were in turn to remunerate the Edomites so that they would not be deprived at Israel’s expense. The Israelites were not the only people group given a possession, as the Lord had allocated the region of Mount Seir as a gift to the sons of Esau. Even with this stipulation the Edomites refused to allow Israel passage (Nm 20:14–21), and so the nation had to pass beyond them to the east by way of the wilderness of Moab, the region immediately east of the Dead Sea.

2:9–15. Just as they were not to provoke Edom, the Israelites were forbidden the same with Moab. The Lord gave Ar (a city or region in Moab about seven miles east of the Dead Sea, perhaps close to the Arnon River; 2:18) to the sons of Lot as a possession, just as Seir had been given to the sons of Esau (v. 5). Verses 10–12 give parenthetical background information about the Emim and how the Edomites came to possess Seir. These verses may have been inserted by a later inspired author to give additional clarifying information and historical backdrop. The clause just as Israel did to the land of their possession (v. 12) seems to refer to some time after the conquest of Joshua. The Emim were the previous occupiers of Moab. They were similar in size and strength to the Anakim and were known as Rephaim. These multiple aliases for tall people (along with the Nephilim [Nm 13:32–33] and the Zamzummin [Dt 2:20]) and a concern to describe their history and territory demonstrate that any information about them was of great interest to the original readers. There was both a fascination and a fear of them, so much so, that information about them would be inserted into multiple accounts in the Scriptures.

That Moab was able to drive out these great, numerous, and tall foes should have strengthened the Israelites’ faith to do the same with the Anakim in Canaan, but instead their hearts melted in their presence (Dt 1:28). This parenthetical insertion functions as an "illustration." If the Moabites could vanquish the Emim and claim their land and the Edomites could do the same with the Horites, then Israel should have no trouble claiming the promised land no matter who currently lived there, especially since they had the Lord to fight with them. After the parenthetical information (vv. 10–12) Moses continued the account by referencing the Lord’s command to cross over the brook Zered (at the southern boundary of Moab, near the southeastern tip of the Dead Sea), which the Israelites did.

2:14–23. The time it took to go from Kadesh-barnea (1:19) to crossing the brook Zered was thirty-eight years. It took that long for all the fighting men of Israel to die as punishment for their unbelief (1:35). As they crossed the border of Moab at Ar and passed into Ammonite territory, the Israelites were not to provoke them either (just as they were not to provoke Edom or Moab) since the Lord had not given them their territory as a possession. Another parenthetical insertion similar to vv. 10–12 appears in vv. 20–23. These verses give information similar to the earlier insertion, but this time they refer to Ammon and whom the Ammonites dispossessed (the Rephaim or Zamzummin) with the Lord’s help in order to live there. A further illustration of a people group who uprooted the previous occupants were the Caphtorim (Philistines) from Caphtor (Crete?) who drove out the Avvim and settled as far as Gaza (on the southeast coast of the Mediterranean Sea). The purpose of this insertion about people groups being displaced was meant to encourage the Israelites that they too, with the Lord’s help, could uproot the original occupants of the land of Canaan.

2:24–31. Picking up from v. 19, Moses then chronicled the next stage of the journey after crossing through Ammon. Instead of peaceful interaction as was the policy with Edom, Moab, and Ammon, the Israelites were now to begin to take possession of Amorite territory east and north of the Dead Sea, then under the control of Sihon, king of Heshbon, a city about 12 miles east and slightly north of the northern tip of the Dead Sea. The Lord began to place the dread and fear of the Israelites within the hearts of all other nations (cf. Ex 15:14–16). At first Sihon was given an opportunity to allow peaceful passage for Israel and to be compensated for any food and water consumed along the way. This was the same policy that was offered to both Edom and Moab.

Sihon refused those terms because the Lord … hardened his spirit and … heart so that he might be delivered into the Israelites’ hand (v. 30). Previously the Lord had hardened the heart of Pharaoh, (Ex 4:21) another foreign ruler, who was also reluctant to grant Israel leave to travel.

This does not mean that Sihon had no free will in this, for he was predisposed on his own (Nm 21:23) not to give them passage, whether because of fear or confidence in his own military strength. The Amorites were not related to the Israelites like the Edomites, Moabites, and Ammonites, and there is no statement that the Amorites were given a possession of land by the Lord as these others were (Dt 2:5, 9, 19). In fact the Lord clearly stated that He is the one who would deliver Sihon and his land over to the Israelites as a possession (v. 31).

2:32–37. The Israelites battled against Sihon … at Jahaz (unknown location). The Lord gave them a definitive victory over the Amorites, by their killing Sihon and his heirs, capturing all their cities, and leaving no survivors. They did allocate the animals and material possessions for themselves as booty. The phrase utterly destroyed (Hb. charam, v. 34) invokes "holy war" terminology and is used several times in the book (3:6; 7:2; 13:16; 20:17). (See the discussion at chap. 7 regarding the ethics of killing noncombatants.) All the Amorite territory from Aroer in the south to Gilead in the north was now under Israelite control. The clause there was no city that was too high for us (v. 36) referred to their city walls. This was a rebuke to the earlier notion that Israel would not be able to conquer the Canaanites because their walls were "fortified to heaven" (1:28). Israel was obedient in that they did not encroach on Ammonite territory (related to Israel via Lot, Gn 19) and went only wherever the Lord commanded them.

3:1–7. After the Amorites were defeated, the next foe to be dealt with was Og, king of Bashan, roughly the region east of the Sea of Galilee. Og gathered his forces to do battle with Israel at Edrei (southern border of Bashan). The Lord told Moses that the Israelites were not to fear him, for just as they defeated Sihon and possessed his land they would do the same with Og and his territory. The Lord did deliver Og and his people into their hands and captured 60 fortified cities and many unwalled towns. Just like Sihon and his people (2:34) all the people of Bashan (also called "Argob") were utterly destroyed, but their animals and possessions were taken as spoils of war. (See discussion at chap. 7 regarding the ethics of killing noncombatants.)

3:8–11. This section summarizes the capturing of the Transjordanian region (beyond the Jordan) ruled by the Amorite kings Sihon and Og. These victories were momentous events meant to strengthen the Israelites’ resolve to do the same in the land of Canaan. This was large territory to control from the valley of Arnon (south) to Mount Hermon (north). Hermon was a natural boundary marker because of its height (9,230 feet) and location. Other nations in the area named it Sirion or Senir. Israel now possessed all the formerly Amorite cities in Gilead and Bashan. Og was the last of the Rephaim (2:11), so he probably ruled over the Amorites because of his lineage and tall stature. His height is confirmed by the dimensions of his bed, which was nine by four cubits (i.e., 13 and a half feet by 6 feet). His iron "bed" may actually be his sarcophagus (coffin), placed after his death on display in Rabbah as a trophy by the Ammonites.

Israel’s Occupation of Transjordan

Adapted from The New Moody Atlas of the Bible. Copyright © 2009 The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago.

3:12–17. The Israelites took possession of the newly conquered territory, which was given to the Reubenites and Gadites and the half-tribe of Manasseh. Reuben and Gad possessed most of the territory ruled previously by Sihon (the valley of Arnon up to and including the southern part of Gilead), and the half-tribe of Manasseh occupied the former kingdom of Og’s lands (Bashan and northern Gilead). Jair of Manasseh received Bashan and named it after himself (Havvoth-jair) since he was instrumental in conquering that area (Nm 32:41). The descendants of Machir of Manasseh settled in the northern part of Gilead.

3:18–20. Moses reminded the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh of their commitment to send their fighting men into Israel west of the Jordan River until their tribal brothers had possessed the land given to them (Nm 32:16–19). Their wives, children, and livestock were permitted to remain home, but the men were not to return until the conquest of Canaan was completed, an accomplishment that took at least five years (Jos 14:6–15; 22:1–4).

3:21–22. Moses then addressed Joshua, his successor, and encouraged him not to fear the Canaanites, for it was the Lord their God fighting for them. He used the victories over Sihon and Og as reminders of the Lord’s future actions when they would cross the Jordan.

3:23–29. Since the Lord used Moses as the military leader during the victories over Sihon and Og, and he saw God’s strong hand at work after his sin at Meribah (Nm 20:12), Moses petitioned God to rethink His refusal to allow him to cross over the Jordan (v. 25). Moses humbly approached the Lord, calling himself God’s servant (v. 24). Moses did not refer to God’s previous workings in Egypt during the exodus as the basis for his entreaty; instead he mentioned God’s present manifestation of His greatness and power since the time of his unbelief.

The Lord angrily rebuffed Moses’ request and asked him not to address him further on this matter (v. 26). The Lord, however, graciously allowed Moses to go to the top of Pisgah so that he could at least survey the land in all directions even though he would never enter it (v. 27; see Dt 34:1–5). God reminded Moses that his role was now to encourage Joshua in his position as leader of the people (31:7–8). Moses gave his final addresses to the nation in a valley in Moab opposite Beth-peor, about five miles northeast of the northern end of the Dead Sea, his ultimate burial place (34:6). The reference to Peor (3:29) alludes to two incidents recorded in Numbers: the place where Balaam prophesied (Nm 23:28) and the rebellion at Shittim, where they worshiped the Baal of Peor (25:1–3). Moses’ final words are spoken against the backdrop of the nation of Israel’s most recent act of serious rebellion.

Moses’ question what god is there? (Dt 3:24), does not imply that he thought that other deities exist. This was a rhetorical device stressing the Lord’s matchless nature and power.

B. An Exhortation to Obey the Law Faithfully (4:1–40)

This chapter reflects much of the form of an ancient Near Eastern treaty, especially second-millennium BC Hittite treaties. While it is not an overt treaty format, there are many similarities. These similarities heighten that this is a deeply relational book, so much so that formalized wording is used.

4:1–2. Up to this point Moses had been chronicling God’s dealing with Israel for the previous 40 years. Now he moved into a more sermonic mode. All of Israel’s history had been chronicled with an eye to motivate the nation as they were getting ready for the conquest of the land. Moses stated his first command in the book—they were to listen (Hb. shema, as in 6:4) to the statutes and the judgments he was teaching them. The Lord’s faithfulness to Israel in the recent past would obligate the nation to obey Him. Statutes may refer to decreed law (apodictic, general commands), and judgments may refer to case law (casuistic, "if-then" commands) and the decisions of appointed judges. The motive clause so that you may live and go in and take possession of the land reflects that God’s blessing and the acquisition of the promised land is dependent on obedience. God’s commands (the verb and the noun are used three times in v. 2) are not to be altered in any way.

4:3–4. By recounting the incident at Baal-peor, Moses gave a clear illustration of the effects of sin and disobedience. There they engaged in Moabite idolatry and immorality (see Nm 25:1–9), so that God clearly manifested His judgment by destroying those who participated in the sin but preserving those who held fast to the Lord. Moses personalized the issue by stating that those who were directly hearing these words understood God’s delivering grace because they experienced that situation firsthand.

4:5–8. Moses gave himself as an example of obedience by stressing that he had been faithful to proclaim the statutes and judgments (v. 5), and so he urged them to keep and do them. Obedience to God’s laws is the path to wisdom and understanding. The law was given to enable Israel to avoid God’s judgment and remain in the promised land. Thus, the nation could fulfill its role as an instrument to glorify God among the nations. But the law was never given, nor intended by God, to be the means whereby Israel would find eternal salvation. When Israel submitted to God’s authority, other nations, when exposed to these laws, would concur that Israel’s laws are of special quality and would thereby acknowledge Israel’s unique status in the world. Moses elaborated that point by stating that no other nation enjoyed as intimate a relationship with their deity as Israel did and that no other nation had a law code as righteous as the one they were receiving. Israel’s God is superior to all other gods because of His personal intimacy and the righteous nature of His law.

4:9–14. The words give heed to yourself (v. 9) occur frequently in the book (6:12; 8:11; 12:13, 19, 30; 15:9), and stress the personal applicational nature of Moses’ instructions. The nation was not to forget what their own eyes saw. Since they did not "see" God directly or worship a representation of Him, their memory of these events had to be embedded in their minds and hearts. In addition to internalizing the teachings within their own hearts, the people were instructed to make them known to their sons … and grandsons. This begins a key aspect of the book of Deuteronomy in that it was to function somewhat as a catechism for the nation, to be passed down from generation to generation.

Moses illustrated the importance of this task by reminding the people of their commitment at Horeb (Mount Sinai) to fear the Lord all of their lives and to teach their children (v. 10; see also 6:20). God’s words in v. 10 would later be identified as the Ten Commandments (v. 13). The focus here is on the nation’s initial experience to laws given at Horeb, hence the restricted reference here to the "Ten Commandments" as compared to all the other injunctions the Lord gave to Israel in the wilderness—yet it also serves to heighten their importance. The Lord’s speaking out of the fire is reminiscent of His initial calling of Moses out of the burning bush (Ex 3:2). The imagery of fire, darkness, and clouds heightens the omnipotence of the Lord. It also shows that since God had no distinct form, no one could fashion an image or statue (an idol) that would represent Him. The Israelites were to focus their attention on the voice that emanated from the fire and the words that were spoken. In Dt 4:13 the term covenant (Hb. berith) is used for the first of 27 times in the book of Deuteronomy, and the phrase the Ten Commandments (lit., "ten words") is also mentioned for the first time.

The commandments were written on two tablets of stone. Perhaps each tablet had the ten words engraved on it rather than some on one tablet and some on the other. The notion would be that each party to this covenant would have their own copy and they would be kept and stored together in the most sacred location in Israel (the ark of the covenant in the holy of holies). Besides being the one through whom the Ten Commandments were delivered, Moses was to teach the Israelites statutes and judgments, to guide the people in properly applying God’s commands once they arrived in the promised land.

4:15–20. Having mentioned that the Israelites saw no form when the Lord spoke (v. 12), Moses expanded upon that and expressly forbade the making of any physical representation of the Lord. All the surrounding pagan nations had idols representing their gods, but the Israelites were not to act corruptly and make any image, whether a male or female figure, or any animal or bird or any insect or fish. The language used in vv. 16–18 echoes the wording used in Gn 1 to describe all the creatures God had created. Since they were merely creatures and not the Creator, it would be inappropriate for them to be worshiped. Also the Israelites were not to worship any of the heavenly bodies either. The sun … moon and … stars were worshiped by other ancient Near Eastern peoples, but the Israelites were not to be enticed by their practices and serve astronomical bodies. The host of heaven were allotted to all peoples, presumably for calendar purposes as well as simply to provide light on the earth (Gn 1:14–15); they were not to be objects of worship.

Moses reminded the people that they had been taken and brought out of Egypt, the dominant superpower of that day, to be His own possession. Israel was God’s inheritance, so He placed special demands on them. Egypt was likened to an iron furnace, used to remove impurities from metal. That is, the Lord used their time in Egypt as a means of purification so they would be fit to enter the promised land.

4:21–24. The importance of purity raised by the furnace imagery in v. 20 is stressed by an example from Moses’ own life. Moses’ act of unbelief when he struck the rock (Nm 20:12) provoked God’s anger, so that Moses was not to enter the good land which the Lord gave Israel as an inheritance (v. 21). This was the third time Moses mentioned his disqualifying sin (Dt 1:37; 3:26), and each time he mentioned that he was missing out on a good land (1:35; 3:25; 4:21–22). Moses again told the people to be watchful (cf. v. 15), lest they forget the covenant and make graven images (v. 23). Worshiping idols was the clearest identifier that the nation had forgotten the covenant. Picking up the fire imagery from vv. 15 and 20, Moses stressed that the Lord … is a consuming fire and a jealous God (v. 24). The Lord demands total loyalty and will not tolerate idolatry in any fashion (a point Moses emphasized in vv. 25–28).

4:25–31. The injunction against idolatry was important not only for Moses’ immediate audience but also for future generations. If any Israelites acted corruptly by making an idol, that would provoke God to anger (v. 25). Heaven and earth would witness to their guilt, and the Israelites would be expelled from the land. Israel would dwindle in size and be scattered among the peoples (vv. 26–27). In a punishment that would fit the crime they would be forced to serve the blind and deaf gods of wood and stone in foreign lands (v. 28). However, exile and punishment would not negate the covenant, for if they sought the Lord wholeheartedly while under God’s judgment, He would respond and restore them (vv. 29–31). This is not merely a hypothetical promise. Rather it is a prediction of the latter days when Israel will return to the Lord and put their trust in Jesus their Messiah (see comments at Hs 3:5; Zch 12:10–14; Mt 23:37–39; and Rm 11:26).

The Lord is a compassionate God, faithful to His promises, who will not utterly destroy them and who will never forget the covenant He established with their forefathers. Verse 29 is sometimes cited in support of the possibility that someone might respond correctly to the light of God found in creation and seek God in such a way that God might save that person even without the gospel (for a critique of this idea, see the comments on Rm 1:18–32). But the verse is spoken to Israel, is based upon God’s specially-revealed covenant promises (not "natural revelation" in creation), is a prophecy about what will happen in the future, and cannot be applied to an individual or a people group outside of His covenant people.

4:32–34. Switching from the future (v. 25), to the past, Moses now asked his audience to reflect all the way back to creation to try to find any situation similar to their experience in the exodus and Sinai events. Israel alone could claim direct revelation of which everyone was a part, not just the priests. No other nation was forged by having been redeemed from another nation as Israel was out of Egypt. Nor had any other nation seen their gods work with such miraculous signs and wonders as the Lord did in redeeming Israel out of Egypt with the plagues, the Red Sea crossing, and the provision of manna in the wilderness. The Lord’s mighty hand and outstretched arm were visible before the eyes of all the people, not just a select few.

4:35–40. The Lord revealed Himself in history so that Israel would learn that the Lord … is God and there is no other besides Him (v. 35). The Israelites needed to understand God’s supremacy and uniqueness and trust in Him before proceeding any further. As Moses had said, God was not seen at Horeb. But His voice was heard out of the heavens, and the tangible expression of His presence was manifested by a great fire (v. 36). God revealed Himself in order to teach Israel His love, sovereignty, and superiority. God loved this generation’s forefathers, particularly the patriarchs, so much so that He chose their descendants after them, and He was personally involved in bringing the nation out of Egypt (v. 37). God’s love is not just an emotion; it is a covenantal relational love that works on behalf of its recipients. Like a sovereign military king, God assisted in the process of driving out foes from the promised land and then distributed that property to His vassal state, Israel, as an inheritance (v. 38). With the repetition of the word today (vv. 38, 39) Moses stressed the immediacy of personally internalizing that their God is God alone and there is no other. Thus Moses’ focus was on God’s nature, leading to His expectation that the Israelites keep His statutes and His commandments (v. 40). If they were obedient they could expect to enjoy prosperity in the land for many generations.

C. Additional Cities of Refuge (4:41–43)

4:41–43. The reference here to the three cities of refuge on the east side of the Jordan may seem awkward. Why would details about these cities be given right after Moses’ address in 1:6–4:40? Moses discussed the cities of refuge in more detail later (see the comments on 19:1–14 for more detail). But here Moses is referred to in the third person (his last specific reference by name was in 1:5), which signals a transition of content. This interlude serves a structural purpose by separating Moses’ passionate plea to keep God’s commandments (4:40) from the statement of the laws and commandments that begins in v. 44.

The insertion here is appropriate because Moses understood that a long, prosperous stay in the land (v. 40) must include this practice of having cities of refuge for a manslayer. Before giving a lengthy account of individual laws and commandments in 4:44–26:19, Moses described this merciful practice that demonstrates due process for offenders who would violate these laws and commandments. While God does demand full obedience, He also is loving and merciful in including protection against extreme punishment of an innocent manslayer. The manslayer is innocent in that he accidentally committed a homicide rather than committing murder with premeditation (cf. Nm 35:31). Inclusion of the cities of refuge laws here provides a qualification for the absolute command in the next chapter (Dt 5:17) "you shall not murder" (John H. Sailhamer, The Pentateuch As Narrative [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1992], 435). The practice of naming the individual cities of refuge in the promised land was to wait until the Israelites crossed the Jordan (Nm 35:9–28), but since they were at that time on the east side of the Jordan, Moses was able to name three cities in territory they had already conquered: Bezer for the Reubenites, Ramoth … for the Gadites, and Golan … for the Manassites. The other three cities would be named after the conquest (Jos 20:7).

III. Moses’ Second Address: The Stipulations (4:44–26:19)

A. The Essence of the Law and Its Fulfillment (4:44–11:23)

4:44–49. Having reviewed God’s provisions in the past, Moses moved toward instructions for the present audience by reiterating the law to prepare them for the future in the land. This paragraph begins the next major section of the book. Verse 44 is one of the key superscriptions that help divide the major sections of the text (1:1; 4:44; 6:1; 12:1; 29:1; 33:1). This is the law (Hb. torah) that Moses set before the sons of Israel. "Law" is best understood not just as legislative material but also as instruction or teaching. "Law" is further classified as testimonies, statutes, and ordinances. These are not different from the law given at Mount Sinai, and are recorded here for the generation of Israelites about to enter the promised land. A historical summary highlighting the key military victories (over Sihon and Og) is restated, as well as the boundaries of the land already in their possession. These victories served as a precursor of what was about to happen once they crossed the Jordan. They are reviewed here yet again to encourage Israel for the future by reminding them of divine successes in the past.

5:1–3. After setting a geographical and historical introduction (4:44–49), Moses moved to his second major speech in the book (chaps. 5–12). As he did earlier (1:1), he summoned all Israel to give their attention to a reiteration of the Ten Commandments as well as additional statutes and ordinances. He began with the command Hear, a frequently used imperative in this section of the book (4:1; 6:4; 9:1). Israel was to do more than listen passively to these laws; they were to learn them and observe them carefully (v. 1). Moses’ goal for Israel was to obey these laws as a reflection of their wisdom and righteousness (4:6–8). The laws were a mixture of "religious laws" and regulations that affected their community and justice. Moses stressed that the Lord … made a covenant with Israel at Horeb (v. 2), not with previous generations but with all those of us alive here today (v. 3). The adult population present at Horeb, nearly 40 years earlier, would have all died because of the sin of rebellion at Kadesh-barnea (Nm 14:1–4), with the exception of Joshua and Caleb. So Moses was probably addressing the children of the first generation of the exodus. These children would have been present at Mount Sinai, but were not sentenced to die in the wilderness (see Dt 1:39–40) as were their parents who lacked faith and obedience. They were "the second generation." Moses, intriguingly, mentioned the third and fourth generations (Dt 4:9), so he definitely was concerned about future generations while mainly addressing the second generation.

5:4–5. Moses further elaborated on the firsthand experience of his listeners as they witnessed God’s establishing of the covenant with Israel. Moses stated that the Lord spoke to them face to face at the mountain from the midst of the fire (v. 4). There is some question as to what was to happen when the nation approached Mount Sinai. In Ex 3:12 God told Moses at the burning bush, "Certainly I will be with you, and this shall be the sign to you [the "you" is singular] that it is I who have sent you: when you have brought the people out of Egypt, you [plural] shall worship God at [lit., "on"] this mountain." Apparently God’s intent was for the entire nation, not just Moses, to go up the mountain. When they ultimately arrived at the mountain, the Lord instructed Moses to tell the people that "when the ram’s horn sounds a long blast, they shall come up to [lit., "on"] the mountain" (Ex 19:13). The trumpet sounded, and instead of going up the mountain to worship God they "trembled" (Ex 19:16), obviously experiencing fear, but allowing their fear to lead them to disobey by not going up onto the mountain. So only Moses went up the mountain and the rest of the nation, because of their fear and unbelief, lost the opportunity to worship God on the mountain as He intended. In Dt 5:5, Moses stressed his role as a mediator standing between the Lord and you. But he also stated that you [plural] were afraid because of the fire and did not go up [lit., "on"] the mountain. This reflects the same reason given in Ex 19:16. As a result of this disobedience the nation lost the opportunity to worship God collectively and now could only approach through mediators. Sadly they could have become a "kingdom of priests" (Ex 19:6) but now would only become a nation "with priests." At this point in the timeline (at Sinai), the Aaronic Levitical priesthood had not yet been established (it is started later (Ex 28:1–4).

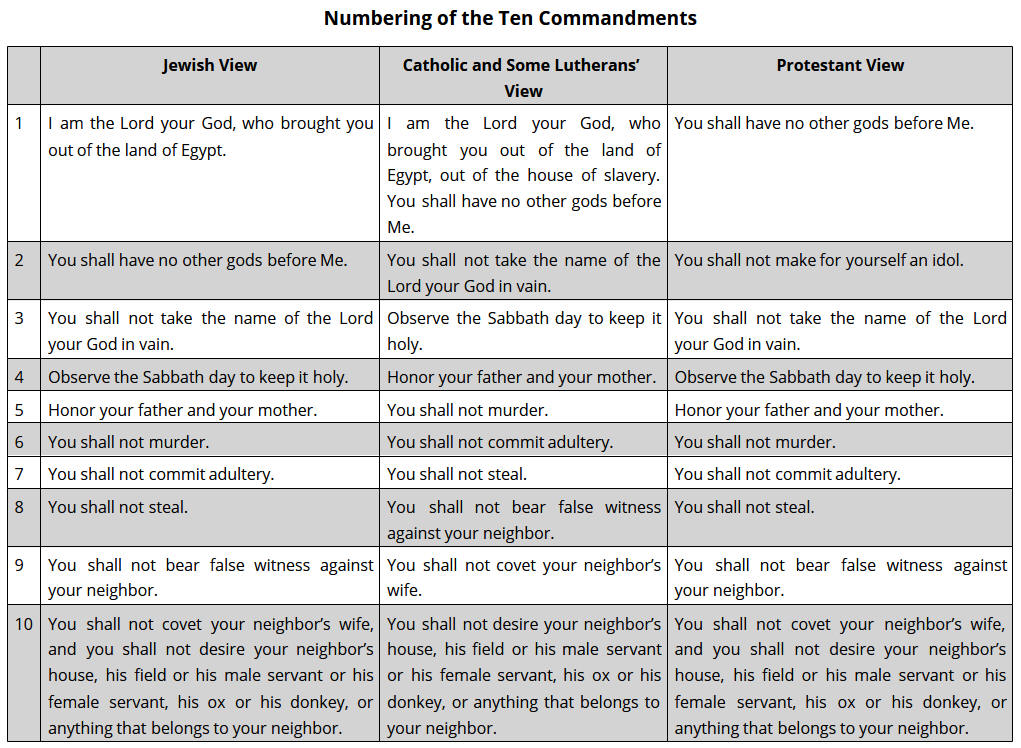

5:6–21. Moses restated the Ten Commandments of Ex 20. (See comments there for a more thorough discussion of each one of the Ten Commandments.) By comparing the two accounts, some variations can be detected. (1) Regarding the Sabbath, in Deuteronomy Moses used the verb "observe" (v. 12) instead of "remember" (Ex 20:8). (2) In Ex 20:11 keeping the Sabbath is related to the creation week, whereas in Dt 5:15 the Israelites were to keep the Sabbath in remembrance of their status as slaves in Egypt. (3) In Deuteronomy, the words as the Lord your God commanded you (Dt 5:12, 15, 16) are not in the Ex 20 account. (4) In Deuteronomy, the order of you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife and … your neighbor’s house (Dt 5:21) is reversed from the order in Ex 20:17. The only variations mentioned so far that bear any significance are the ones concerning the Sabbath. Moses strengthened the injunction from Ex 20:8 to not just "remember" but "observe" (v. 12) the Sabbath. He also drew upon their recent experience as slaves in Egypt rather than upon the more distant creation week. (5) Various traditions differ in their numbering of the Ten Commandments, as seen in the chart below.

The Ten Commandments (Decalogue) seem to begin with the more prominent commandments. The Decalogue is given priority in the book of Deuteronomy as it is the first important piece of legislation Moses gave. It is the core of the theological message of the book, and many scholars see it as a basic outline for the content of chaps. 12–26 (John Walton, "Deuteronomy: An Exposition of the Spirit of Law," Grace Theological Journal 8.2 [1987], 213–25). The Ten Commandments have traditionally been divided into two categories: those that govern one’s vertical relationship with God (1–4) and those that govern one’s horizontal relationship in community with others (5–10).

5:6–7. The First Commandment: The foundation of the Ten Commandments is based on God’s salvific event—the exodus from Egypt. As the most significant deliverance event in the OT, the exodus functions as the theological core of the first testament much as the death and resurrection of Jesus do in the NT. On the basis of God’s personal involvement in bringing them out of slavery out of the land of Egypt, He commanded that they have no other gods before Me. This does not necessarily assume the existence of other pagan gods. It is stressing that no Israelite was to worship any deity whether believed to be real or not. Even if other nations assumed the existence of deities, Israel was not to worship them or acknowledge their presence. God was to be the exclusive, sole focus of their worship and service and was not to be rivaled by anyone or anything.

5:8–10. The Second Commandment: Related to the first commandment, Israel was forbidden to make into an idol any physical representation of God of any kind. Since God created everything, no created likeness of any object in the sky, on earth, or in water should ever be the focus of worship. This command also extended to forbidding the making of any tangible representation of the invisible Lord God of Israel. The reason for this prohibition is that the Lord is a jealous God, a repeated theme in the book (4:24; 6:14–15). This emotion befits a call to exclusivity in a covenant relationship, which Israel had with their God. If Israel attached her affections spiritually to some other divine being, God’s jealousy would lead Him to punish the nation. A warning is attached to violation of this commandment: God will visit the iniquity of the fathers on the children, and on the third and the fourth generations of those who hate Me. Idolatry is equated with hating God, and parents who engage in idolatry will influence their children and grandchildren negatively. Yet for those parents who love the Lord and keep His commandments, there is a spiritual legacy that extends multigenerationally. Hence, the reference to multiple generations has nothing to do with "generational curses" but rather normal consequences. An outward keeping of the commands was inadequate; God wanted them to love Him as they kept His commandments.

5:11. The Third Commandment: The command not to take the Lord’s name in vain is more than refusing to use any of His various appellatives in profanity. The word "vain" is also used in v. 20 in the context of "false" testimony, so its primary usage here would narrow this prohibition against using the Lord’s name in giving false witness. It would extend to any deceptive use of His name in any verbal speech act, such as oaths and promises. His name is an extension of His person and should be respectfully appropriated in all conversations.

5:12–15. The Fourth Commandment: The injunction to observe the Sabbath day is the first of two positively stated commands. The verb observe is used here instead of the verb "remember" (Ex 20:8), implying a more active physical response than merely recalling something in one’s mind. This command, more than any other, shows the most variation in wording from the Exodus account and demonstrates that additional significance had been attached to Sabbath-day observance compared with 40 years earlier. Deuteronomy does not repeat the teaching of Exodus but expands on the exposition originally given at Sinai. This command has no explicit connection to the creation week as in Ex 20. Here the focus is on relating the observance of Sabbath as a memorial of the exodus event. The seventh day was set apart from the others as a day to remember God’s act of creation, but now it is fused with His work of redemption. This command is very specific as to who should observe it: you or your son or your daughter or your male servant or your female servant or your ox or your donkey or any of your cattle or your sojourner who stays with you. The Sabbath was to be observed by members of the covenant community but also by foreigners (whether visiting or employed as servants), and it also extended to animals. God’s act of deliverance was to be marked by a day each week when all work ceased and even household servants and animals could enjoy a mini "deliverance" themselves in honor of God’s redemptive work of Israel. This is the only command in this list that is not repeated in the NT. It is important for NT believers to set aside time to reflect upon God’s goodness and grace, but a day where no physical labor is even attempted does not have NT biblical authority. The apostle Paul clearly stated there that no one is to act as your judge in respect to observing a Sabbath day (Col 2:16).

5:16. The Fifth Commandment: The charge to honor your father and your mother is the first of the horizontal commandments and the second in a string of positive injunctions (cf. Lv 19:3). This commandment addresses the first and primary relationship among humans. The command probably focuses on the attitude of adults toward their aging parents, since the Decalogue is not elsewhere specifically addressed to the young (cf. v. 14). Moreover, Jesus understood this commandment as applying to adult children (cf. Mt 15:4–6). However, the young are not excluded, as Paul noted in Eph 6:1–2. This command includes a promise of long life and a prosperous stay in the land.

5:17. The Sixth Commandment: The word murder can refer to both premeditated and unintentional killing. Special consideration will be given later to unintentional manslaughter (19:1–13), so the primary focus in this context is on premeditated murder. This commandment cannot be applied to soldiers fighting in a war or to executions of criminals sentenced to capital punishment since those actions are mandated elsewhere (Gn 9:6; Nm 31:7).

5:18. The Seventh Commandment: The prohibition against adultery highlights the importance of yet another human relationship (cf. 5:16–17). While other sexual sins are forbidden elsewhere, the sexual faithfulness in a marriage relationship is emphasized here because it speaks of a covenantal relationship. Faithfulness to a spouse pictures faithfulness to God.

5:19. The Eighth Commandment: While stealing is wrong (cf. Ex 22:1–13), the juxtaposition of this prohibition with other commands dealing with horizontal human relationships seems to narrow this command more against kidnapping and manstealing than stealing someone’s physical property, though such pilfering is not excluded here. Kidnapping violates a covenant relationship by removing someone from his family for financial gain.

5:20. The Ninth Commandment: The command to not bear false witness against your neighbor deals with how one treats people in a legal environment and once again speaks of faithfulness within the covenant community. Integrity and truthfulness are to characterize God’s people.

5:21. The Tenth Commandment: The last prohibition in the Decalogue is the only command that is not clearly visible in outward behavior. Coveting is a sin of the heart and is the basis of all the other sins addressed in the Ten Commandments. The order of "wife" and "house" is reversed from the Exodus account, and "field" is added. This may reflect the rising status of women’s rights in conjunction with the matter of inheritance laws granted to Zelophehad’s daughters (Nm 36).

5:22–26. The sacredness of the Ten Commandments is highlighted because of the unforgettable backdrop of their original setting from the midst of the fire, of the cloud and of the thick gloom, with a great voice and because He added no more commands. While the people were afraid of what they were experiencing, they sent all the tribal heads and elders to act as mediators. A popular notion (Jdg 13:22) was that if anyone saw God he or she would immediately die (although it was not the case with Jacob in Gn 32:30 and later with Moses in Ex 33:11). The nation saw that Moses was still alive after his encounter with God. Still they were not convinced that they would survive seeing God, so they volunteered Moses to be the intermediary, promising that they would obey whatever he received from God.

5:27–6:3. The Lord was pleased with the people’s response to hear and obey (do) His word, and He hoped that this same attitude of reverence and submission would always be characteristic of them (vv. 28–29). After they were dismissed to their tents, Moses was to remain with God and receive additional legislation for the people to observe … in the land (v. 31). With a rhetorical flourish, Moses associated the nation’s obedience with a long prosperous stay in the land they were to possess.

The subject matter at the end of chap. 5 dovetails with the beginning of chap. 6 as shown in the chiasm to follow. All pivot on the injunction in v. 32, you shall not turn aside to the right or to the left, summarizing the nation’s need for strict obedience to God’s commandments.

Moses’ purpose of structuring this passage in this way is to clearly define these verses as a unit (in this case it crosses a chapter division!) and to focus on the outside verbal injunction (to "hear/listen" 5:27/6:3) and the pivot in the middle where the nation was not to turn aside to the right or to the left (5:32).

To live long in the land (5:31, 33) the nation was to listen to (hear, 5:27; 6:3) God’s commandments (5:29; 6:1) by fearing (reverencing; 5:29; 6:2) Him and not deviating (5:32) in their obedience.

Structure of Deuteronomy 5:27–6:3

A hear (Hb. shema) … speaks (Hb. dabar) to you (5:27)

B fear … keep all My commandments … sons (5:29)

C commandments and the statutes and the judgments … teach (5:31)

D land which I give them to possess (5:31)

E you shall observe to do just as the Lord your God has commanded you (5:32)

F you shall not turn aside to the right or to the left (5:32)

E’ You shall walk in the way which the Lord your God has commanded you (5:33)

D’ land which you will possess (5:33)

C’ commandment, the statutes and the judgments … teach (6:1)

B’ son … fear … keep … His commandments (6:2)

A’ listen (Hb. shema) … promised (Hb. dabar) you (6:3)

6:4. This is one of the key verses in the entire OT. It has been designated, "The Shema," which comes from the Hebrew word Hear. The summons for Israel to hear is stated here for the second time in the book (5:1) and clearly is meant to cause the nation to pay strict attention and obey the instructions of this passage. This verse is the core credo statement of Judaism. Yet it is challenging to translate because of the number of ways in which the Hebrew can be understood. The first words can be interpreted as either a predicated statement, The Lord is our God (supplying a helping verb), or as a nominal phrase ("The Lord our God"). The predicated statement is unlikely here since the clause "The Lord is our God" is not likely to be understood that way in any of the 21 uses in the book (cf. 1:6, 20; 6:20, 24). The real crux is whether the last word in the verse is to be translated as an adjective "one" (The Lord is one) or as an adverb "alone" ("the Lord alone"). Either translation is possible, and perhaps this is a rare instance of intentional ambiguity to allow for both notions. The wording, however it is translated, would imply monotheism, and other passages in Deuteronomy (e.g., 32:39) support that notion as well. If it is an adjective ("one"), then this would allow for the doctrine of the Trinity since elsewhere in the Pentateuch the Hebrew word ’ehad can designate a compound unity as in the case of two people (Adam and Eve) being "one" (’ehad) flesh (Gn 2:24). In light of the immediate context in Dt 6, it may be better to take the last word as an adverb. The Ten Commandments clearly call for the worship of God alone ("no other gods before Me," 5:7), and verses in the immediate context (5:13–15) elaborate further on worshiping Him exclusively for His uniqueness. Although the doctrine of the Trinity is an important truth, it does not seem to be the focus in this verse.

6:5. The faith statement of the Shema is followed up by the charge to love the Lord your God, implying complete devotion to Him and not just emotional attraction. Moses’ sense of love is to express loyalty to Him with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. The whole person is to express this loyal devotion to God. The heart was generally associated in Hebrew thinking with the mind, the soul denoted the innermost being or emotions, and might refers to doing the previous two injunctions exceedingly (lit., "very, very much"). The repetition of the word "all" shows that Israel’s commitment to the Lord was to be undivided and complete.

6:6–9. Moses stated that these divine instructions were to be on your heart. Since "heart" refers more to the mind and intellect than to one’s emotions, the Israelites were to meditate and reflect on these commandments, as Jos 1:8 stressed later. These were to be taught diligently to their children, not in the sense of a formalized education, but throughout the everyday common experiences of life: when you sit in your house and when you walk by the way and when you lie down and when you rise up. The command to bind them as a sign on your hand and … as frontals on your forehead (v. 8) designates that God’s instructions were to be constant reminders to guide all their actions (suggested by "hand") as well as how they viewed the world (suggested by "forehead"). They were also to be written on the doorposts of your house and on your gates, meaning that God’s laws were to be obeyed in the home ("doorposts") and in the greater community ("gates"). Although later Judaism later took these commands literally in the use of phylacteries (Mt 23:5) and mezuzoth (Dt 6:4–9 and 11:13–21 written on miniature scrolls, placed in small cases, and affixed to a home’s doorposts), it is better to understand these injunctions as to be taken figuratively.

6:10–15. These verses contain a warning against Israel being too complacent after they entered the land and were enjoying the bounty and prosperity of its provisions. The Israelites would enjoy the fruit of others’ labors and in which they did not personally invest (vv. 10–11). But in partaking of those wondrous blessings there was the danger of not being watchful and forgetting the Lord who brought them out of Egypt … the house of slavery (v. 12) This thought is later echoed in Pr 30:7–9. Prosperity has a way of causing forgetfulness. The way to prevent spiritual amnesia is to fear only the Lord and worship only Him (v. 13) When Satan tempted Jesus, offering Him all the kingdoms of the earth if Jesus would only bow down to him, Jesus cited this verse (Dt 6:13) to rebuke him (see the comments on Mt 4:10).

Moses then expanded on the topic of the Lord’s uniqueness and exclusivity. They were not to follow after other gods, specifically those of the neighboring nations for the Lord your God … is a jealous God. God wanted their complete devotion and loyalty; if they forgot Him He would wipe them off the face of the earth. This does not mean that God would potentially break His promise to Abraham (Gn 12:1–8; 15:1–21; 17:1–22), but rather that disobedience might cause Him to destroy a generation completely and start Israel anew.

6:16–19. The Israelites were further instructed not to put the Lord your God to the test, as you tested Him at Massah (Ex 17:7). There they lacked water, and instead of trusting God to meet their needs they grumbled against Him. Jesus cited Dt 6:16 when rejecting the Devil’s temptation to jump from the pinnacle of the temple and let His angels rescue Him (see the comments on Mt 4:5–7). For the nation to have success and longevity in the land they needed to adhere diligently to God’s commands.

6:20–25. Here Moses returned to the subject of teaching children, begun in 6:7. He instructed parents to have a ready response when their offspring asked them the meaning of all these laws (v. 20). They were to rehearse the history of their slavery in Egypt and also to tell of the Lord’s miraculous deliverance, bringing them out of Egypt and into the land which He had sworn to our fathers (vv. 21–23). As a result of God’s work on their behalf they were to obediently observe all these statutes, to fear the Lord [their] God for [their] good always and for [their] survival (v. 24). Obedience would result in righteousness (v. 25). This may have several possible meanings. It could refer to (1) physical deliverance (Is 46:13), (2) saving acts accomplished on their behalf by God (Jdg 5:11), or (3) a right relationship with the Lord as in the case of Abraham (Gn 15:6). But in this context it seems best to understand it in the sense of enjoying the covenant blessings (prosperity and longevity in the land, cf. Ps 24:5, where righteousness is synonymously paired with blessing), since keeping the law is not the basis for righteousness but is instead the outward demonstration of covenant loyalty.

7:1. In keeping with the concept that the book of Deuteronomy is loosely based structurally on expounding the Ten Commandments (see discussion on Dt 5:6–21), chap. 7 expands on the first commandment, which states that Israel was to worship no other gods. By annihilating the current occupants and by tearing down any vestiges of their worship, Israel would be more apt to live in obedience to the first commandment.

This verse lists seven nations, which connotes the totality of the population of the Canaanite people groups. Amalek is another group of people living in the land of Canaan (Ex 17:8–16; Nm 13:29) not mentioned in this list, so the list was not meant to be exhaustive. These Canaanite nations were collectively greater and stronger than Israel. Many of the nations listed are not readily identifiable. The Hittites had a clear presence in Canaan already (Gn 23:10; 27:46) but are historically most associated with Asia Minor. The Girgashites, who descended from Noah’s son Ham (Gn 10:15–16) were possibly located in Asia Minor or the Transjordan. The Amorites had an established connection with Canaan (Gn 14:13). This nation denoted the Canaanite nations in general (Gn 15:16) and occupied territory in Canaan (1:19–20) as well as the Transjordan (Nm 21:13). The Canaanites, who descended from Noah’s grandson Canaan (Gn 10:6), were seen as the ancestor of many of the nations in the region and had far-reaching territorial boundaries "from Sidon as you go toward Gerar, as far as Gaza; as you go toward Sodom and Gomorrah and Admah and Zeboiim, as far as Lasha" (Gn 10:19). The Perizzites are often combined with the Canaanites (Gn 13:7; 34:30) as an entity that stands for a larger grouping of nations. They were elsewhere located in the hill country of Canaan (Jos 11:3). The Hivites descended from Ham (Gn 10:17). They were generally located in the central part of Israel from Gibeon (Jos 9:7; 11:19) to Shechem (Gn 34:2). The Jebusites descended from Ham’s son Canaan (Gn 10:16). They were in the hill country of Canaan (Nm 13:29) and were the original inhabitants of Jerusalem (Jos 15:63).

7:2–6. God’s call to exterminate all the people groups currently occupying the land has been thought of as unloving and severe. Several factors may help explain the reasons such a command was given. First, all people are sinners and are under God’s judgment. Only by God’s mercy are any people groups allowed to live. Second, the context (7:10) implies that these nations hated the Lord, so they were not neutral toward the God of Israel. Third, Gn 15:13 states that God had been patient with these nations for hundreds of years and had delayed their punishment until this exact point in history. God was giving the Canaanites as much time as was needed to become as wildly corrupt as possible. God’s command to annihilate them is tied to this circumstance alone and should not be used as justification for any genocide. Fourth, if Israel let these nations live in their land, their pagan practices would be propagated and emulated by the people of God (Dt 20:17–18). Fifth, the command to exterminate the Canaanite nations is mitigated somewhat by God’s allowing individual non-Jewish women like Rahab and Ruth to enter into the messianic line. God always had a plan that included the nations (Gn 12:2–3), but He promised Israel they would occupy this land as gift from Him. Israel was actually to offer peace with any nation outside her borders (Dt 20:10–18), but to exterminate any pagan nation within its borders. Even though not specifically mentioned here, extending annihilation to Canaanite children is an affront to modern sensibilities. The totality of this destruction is connected in this text (v. 3) to the prohibition of assimilation to other nations. If these children were allowed to live they would become a snare for Israel. The killing of all Canaanites, including the children, served as a preventative measure against assimilating with the Canaanite way of life and as a stark reminder that Israel was to be set apart exclusively for God.

A major concern in these verses is that there was not to be any intermarriage with people of other nations in the land, lest they turn their sons away from following Me to serve other gods (v. 4). Any vestige of their religious practices like their altars … sacred pillars (male fertility objects), Asherim (female consorts of Baal), and images was to be torn down or burned (v. 5). The reason for this extermination policy was that Israel was a holy people to the Lord (v. 6). He had chosen them to be a people for His own possession out of all the peoples who are on the face of the earth (v. 7). The initiative was God’s, and He wanted them be His exclusive representative nation.

7:7–11. These verses give the grounds for God’s selection of the nation. The Lord did not set His love on them because they were vast in number, for they were the fewest of all peoples (v. 7). God’s sovereign covenantal love was set in motion on one man Abraham (Gn 12:1–2), whose family then grew in size to 70 (Dt 10:22) and then ultimately to the size it was at this point in their history. The Lord kept His oath with their forefathers and redeemed Israel by bringing them out with a mighty hand from slavery in Egypt (v. 8). By doing so He was demonstrating that they truly were "His own possession" and retained this status (v. 6). This status was another outgrowth of the first of the Ten Commandments—that they were to have no other gods before Him. The nation was not to worship any other possible god because the Lord chose them, redeemed them, loved them, and kept His promise to them; therefore they were exclusively His. Israel was to reflect on the nature of their God, remembering that He is faithful, so faithful in fact that He continues His lovingkindness to a thousandth generation with those who love Him and keep His commandments (v. 9) This expression signifies that He will be faithful in His covenant-love to them forever. However, those who hate (reject) Him will be repaid without delay (v. 10). While His faithfulness is sure and long, His judgment will be direct and swift. Moses concluded this section with another reminder to keep the commandment and the statutes and the judgments (v. 11). These multiple designations of the law often serve as division markers within the text (4:1, 40; 6:1, 20; 8:11; 10:13; 11:1, 32; 12:1; 26:16; 30:16).

7:12–16. When the Israelites would give attention to and obey these laws, the Lord would honor His side of the covenant and bestow His lovingkindness on them (v. 12). These blessings would flow out of His love and result in their increased fertility, not only in the number of offspring but also in abundant harvests and flocks (vv. 13–14). This blessing would be evident to all because there would be no barrenness throughout the land and no illness would befall them. In addition, their military conquests would be successful. In the process they should not be tempted to show mercy to the Canaanites because their negative influence could lead them astray (v. 16). Moses again emphasized the first of the Ten Commandments by enjoining them not to serve their gods, for that would be a snare to you (v. 16).

7:17–26. Moses now addressed Israel’s potential fears in carrying out these injunctions to wipe out the Canaanites from the land. If they thought they did not have the strength to dispossess them, then Israel should think of what the Lord had done for them in the exodus event (vv. 17–19). In addition the Lord would send the hornet against them to deal with any who would try to escape (v. 20). The hornet may refer to literal insects that would come alongside Israel’s soldiers to assist them. Or the hornet may refer to some sort of foreign military force that "softened up" the Canaanites before the Israelite conquest. Or metaphorically it may mean that the Canaanites would respond in panic to their arrival as if they were being attacked by a swarm of hornets. Exodus 23:27–28 uses this word in tandem with the word "terror," so the metaphorical view is the more likely. Whatever the hornet was, the Israelites were not to fear the enemy because God was in their midst and He would help clear away these nations (v. 22). This conquest would take place gradually (little by little). Otherwise the land would too quickly be void of those who could keep the population of wild beasts from growing too quickly. The Lord would throw the nations into great confusion and would deliver their kings over to them for execution so that their exploits and their legacy in the land would be forgotten (vv. 23–24). During the conquest the graven images were to be totally burned up, even if they were made of precious metals that could be extracted. No religious objects were to be taken as spoil and brought into any of their houses, regardless of monetary value (vv. 25–26).

8:1. Moses reiterated that the Israelites needed to be careful to obey all that he was commanding them so that they may live … multiply, and … possess the land … the Lord promised to give them. Moses’ repeated use of the word today in the book of Deuteronomy (2:18; 9:3; 11:32) highlights the need of that generation to respond appropriately to the covenant, but it also adds a sense of immediacy for all subsequent readers to respond appropriately to God’s commands as well.

8:2–10. Remembering the Lord’s past guidance during their 40 years in the wilderness gave motivation for Israel to keep the Lord’s commandments in the future. God allowed their time spent in the wilderness to humble them and to see if they would obey the covenant (v. 2). God was testing them, not because He was ignorant, but so that Israel’s commitment or lack thereof could be disclosed. The Lord ordained that they experience physical hunger, and then He supernaturally gave them manna. He did this to provide what their physical bodies needed and to emphasize that man does not live by physical bread alone, but also by spiritual food (commandments and teaching) that proceeds out of His mouth (v. 3). This mention of food echoes back to the first temptation in the garden of Eden—which pertained to food. Jesus cited this (Dt 8:3) in resisting the Devil’s temptation for Him to turn stones into bread (see the comments on Mt 4:4).