EXODUS

Kevin D. Zuber

INTRODUCTION

The title of Exodus in Hebrew (w’elleh semot) is taken from the first few words of 1:1, "Now these are the names." This phrase, which also appears in Gn 46:8, introduces the list of the persons who "came to Egypt with Jacob." Since the book begins with an adverb of time, "Now," as well as this unmistakable connection with Genesis, it is evident that Exodus was meant to be a continuation of the narrative of Genesis. Furthermore, the subject matter of the tabernacle (the last major portion of Exodus) and the subject of the functions of the Levitical priests who served in the tabernacle (the first chapters of Leviticus) tie the second and third books of the Torah (Law) or Pentateuch (five books) together. Plainly the Torah was intended to be read as one book with five volumes, not five separate books.

The title of the book in the English Bible is derived from the Septuagint (the ancient Gk. version of the OT) through the Latin (exodus is the Lat. of the Gk. exodos which means "going out"). This title is, of course based on the major theme of the first part of the book, the "exodus," the departure of the nation of Israel from bondage in Egypt. This departure was the first vital step on a journey to the land of promise (cf. 3:8, 17; 13:5; 32:13; 33:1; 34:11–12). That journey, which began with the exodus, is taken up again in the book of Numbers (cf. Nm 15:2) only to be delayed by fear and unbelief (see commentary on Nm 13; 14). When the story of that journey is taken up once more in Deuteronomy (cf. Dt 1:6–8), it ties together the narrative of the nation’s promise from the Lord (Gn 12–50), deliverance by the Lord (Exodus), provision, preservation, and protection from the Lord (Exodus–Numbers), and preparation (for entering the land, Deuteronomy). Viewed in this way "Exodus forms the heart of the Torah" (Walter C. Kaiser Jr., "Exodus," in vol. 2 Expositor’s Bible Commentary, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990], 287).

Author. The liberal and critical view that the Pentateuch is a late (c. 550 BC) compilation of earlier materials from a variety of somewhat incommensurate sources (i.e., the JEDP theory; see Bill T. Arnold, "Pentateuchal Criticism, History of," in Dictionary of the Old Testament Pentateuch, ed. T. Desmond Alexander and David W. Baker [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2003], 622–31; see also Kaiser, "Exodus," 288, and John J. Davis, Moses and the Gods of Egypt [Winona Lake, IN: BMH Books, 1986], 45) stands in stark contrast to the view indicated in the text itself that Moses himself was the author of the Pentateuch. Kitchen simply states, "The basic fact is that there is no objective, independent evidence for any of these four compositions (or any variant of them) anywhere outside the pages of our existing Hebrew Bible" (Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003], 492).

Several lines of evidence support Mosaic authorship of Exodus. First, internal evidence can be found in Exodus in passages where Moses is instructed to write things down (17:14; 34:4, 27–29) and where the text records that "Moses wrote down all the words of the Lord" (24:4; cf. Nm 33:1–2; Dt 31:9). Second, "the great abundance of details reflecting an eyewitness account would seem to support" Mosaic authorship (Davis, Moses and the Gods, 46; note especially the account of Moses’ call [chaps. 3 and 4] when only he and the Lord were present; no one but Moses could know the details of this conversation). Third, other OT books indicate Mosaic authorship of Exodus and the Pentateuch (cf. Jos 1:7; 8:31–32; 1Ki 2:3; 2Ki 14:6; Ezr 6:18; Neh 13:1; Dn 9:1–13; Mal 4:4). Fourth, the NT also clearly affirms Mosaic authorship. "Mark 12:26 locates Exodus 3:6 in ‘the Book of Moses,’ [cf. Mk 7:10] while Luke 2:22–23 assigns Exodus 13:2 to both ‘the Law of Moses’ and ‘the Law of the Lord’ " (Kaiser, "Exodus," 288). John likewise confirms Moses’ authorship of the Law (Jn 7:19; cf. 5:46–47; Ac 3:22; Rm 10:5).

Finally, it is eminently plausible that Moses wrote the books attributed to him, for he "was educated in all the learning of the Egyptians and he was a man of power in words and deeds" (Ac 7:22).

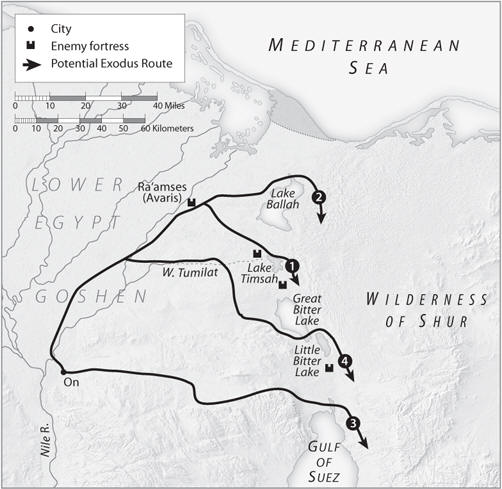

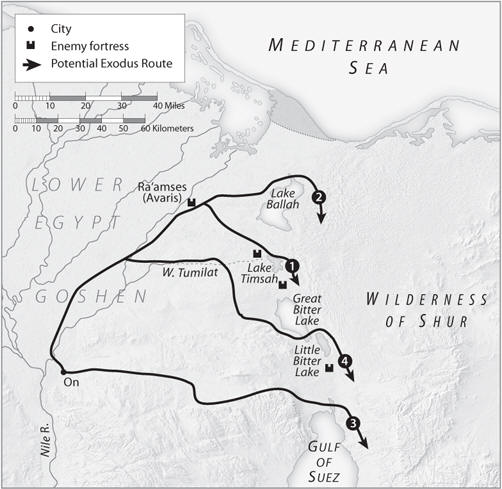

Date. The contemporary debate on the date of the exodus itself is a question mainly reserved "for those who take the biblical record seriously" (John H. Walton, "Exodus, Date of," Dictionary of the Old Testament Pentateuch, ed. T. Desmond Alexander and David W. Baker [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2003], 258–72). Broadly speaking, the issue has come down to two possible dates: an early date at the time of the later pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty (c. 1580–1321 BC) or a late date at the time of the 19th Dynasty (c. 1321–1205 BC) (cf. Kaiser, "Exodus," 289).

Advocates of the late date point to the identity of the storage cities identified in 1:11 as Pithom and Raamses and identify the latter with Raamses II of the Nineteenth Dynasty. Late date advocates also point to certain strands of archaeological data to bolster their view (cf. Walton, "Exodus, Date of," 263; Kaiser, "Exodus," 289).

On the other hand, the early date is supported by two texts of Scripture. One is found in Jdg 11:26, which indicates that three hundred years had passed between entrance of the nation into the land (the conquest of the land) and Jephthah’s rule as judge. The second text is 1Ki 6:1; this verse states clearly that the exodus happened 480 before the fourth year of Solomon. If the latter is dated as 966/5 BC (cf. Davis, Moses and the Gods, 34; see commentary on 1Ki 6:1) then the exodus itself took place 1446/5 BC, a date much in line with the time indicated in Jdg 11:26 (when one adds the years between the exodus itself and the start of the conquest; cf. Nm 14:34). As for the city being named after Raamses II, the city could have been built earlier by Israelite slaves and renamed after Raamses II came to power. Then later copyists may have updated the names (even as they did with Laish, substituting Dan, Gn 14:14; see "The Presence of Anachronisms" in the section on the Documentary Hypothesis in the introduction to Genesis).

The matter of the date of the exodus is related to the question of the identity of the different kings and pharaohs in the narrative of Exodus. Since the entire time of bondage was over four hundred years (cf. Gn 15:13; Ex 12:40; Ac 7:6), it is obvious that the king who began the oppression is not the one who was alive at the time of the exodus itself. The "new king" (1:8) was probably one of the Hyksos (c. 1730–1570 BC), a Semitic people who conquered Egypt briefly in the era before the 18th Dynasty (cf. Davis, Moses and the Gods, 40, 53; Ronald F. Youngblood, Exodus: Everyman’s Bible Commentary [Chicago: Moody, 1983], 23; cf. Kaiser, "Exodus," 305n8). The early date of the exodus places that event late in the 18th Dynasty (which ran from c. 1580–1321 BC), thus the "Egyptians" mentioned in 1:13 were those (probably pharaohs Kamose and Ahmose I, first rulers of the 18th Dynasty) who expelled the Hyksos, but persisted in the oppression of the Hebrews. The king who "spoke to the Hebrew midwives" (1:15) was most likely Thutmose I, during whose reign Moses was born (1525 BC). After Thutmose died his son Thutmose II ruled only briefly and was followed by Queen Hatshepsut. Her stepson was Thutmose III and he was the pharaoh from whom Moses fled (forty years before the exodus; 2:15) and the one whose death was noted in 4:19. His son Amenhotep II was the pharaoh at the time of the exodus itself (cf. Davis, Moses and the Gods, 42–43; Youngblood, Exodus, 24–25).

Purpose. Obviously the book of Exodus supplies a crucial link in the historical narrative of the nation. Even as the Lord made an unconditional promise to Abram and his descendants (see Gn 15), He informed Abraham that his descendants would be "strangers in a land that is not theirs" and that they would be "enslaved and oppressed" but ultimately they would "return here"—to the land of promise (see Gn 15:13–16). Exodus provided the details of the nation’s bondage and deliverance to impress upon the generation that experienced the exodus (and subsequent generations) that the enslavement and the great deliverance they had experienced was in accord with the sovereign and gracious plan and purposes of God.

Furthermore, the book was meant to impress upon the nation the privilege and importance of the presence of God among them. The tabernacle (along with the instructions for the priests in Leviticus) was a tangible reminder of the importance of careful, serious, and solemn worship; one could hardly be flippant about approaching God in a venue like the tabernacle. And of course Exodus contains the first writing of the Decalogue—the Ten Commandments—which was the gracious gift from the Lord to encourage the people to live in such a way that they might enjoy the blessings of His sovereign plan for them and His awesome presence with them.

In the light of the failure of that exodus generation to enter the land of promise, the second generation, that of the conquest (see Joshua), would have read this part of the Pentateuch (Exodus) as both encouragement (the Lord keeps His promises, specifically to live in the land of promise) and warning (the Lord is to be trusted and obeyed for any generation to know and enjoy His promises) (see Dt 28).

Themes. No incident in the history of the nation is referred to more frequently by the rest of the OT than is the exodus. The theme of deliverance from bondage—redemption—is central to the theology and history of the OT, and this theme is at the heart of the first part of the book of Exodus. The second major theme in Exodus is worship. This theme is highlighted by instructions about and construction of the tabernacle. The details of the construction and furnishings of the tabernacle testify to the central role worship was to play in the life of God’s people.

Overall, the major theme of the book of Exodus is theology proper, the study of God. Few other books can rival the breadth of theology, teaching about God, revealed in this book, including the revelation of the person, attributes, and perfections of God. The theology of Exodus is foundational for understanding the person and program of the Lord God in the remainder of the OT and indeed the whole Bible. In Exodus the Lord is shown to be the God who keeps His covenant promise to the nation. He is the God who calls, empowers, and employs unlikely but submissive servants; He is I AM (cf. 3:14). He is revealed as the One who demonstrates His sovereign power and authority (while idols and false gods are proven impotent). He is the holy God who desires His people to live before Him in holiness (and to that end He gave them the Ten Commandments). His very character is revealed in the law; "the law is something of a transcript of the nature of God" (Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1998], 820). He is displayed as the longsuffering and faithful God who cares for, provides for, and protects His people. He is revealed as the awesome and holy God who nevertheless desires to dwell in the presence of His people (in the tabernacle); He is the worthy God who demands true worship.

OUTLINE

I. Redemption: The Lord Delivered the People of Israel from Bondage in Egypt (1:1–18:27)

A. How the Bondage Began (1:1–22)

1. Opening Genealogy (1:1–7)

2. The Oppression Begins (1:8–14)

3. The Oppression Continues (1:15–22)

B. Moses: Early Life and Calling (2:1–22)

1. Moses’ Mother Endeavors to Save Her Son (2:1–4)

2. Moses’ Life Is Preserved by Pharaoh’s Daughter (2:5–10)

3. Moses’ Failure (2:11–15a)

4. Moses’ Sojourn in Midian (2:15b–22)

C. The Call of Moses: Reluctance and Compulsion (2:23–4:26)

1. The Nation’s Bondage Recalled (2:23–25)

2. Moses Called to the Burning Bush (3:1–9)

3. Moses Commissioned by "I AM WHO I AM" (3:10–4:17)

a. Moses’ First Objection (3:10–12)

b. Moses’ Second Objection (3:13–17)

c. A Preview of Coming Events (3:18–22)

d. Three Signs and One Spokesman for Moses (4:1–17)

4. Transitions (4:18–26)

D. The Return of Moses: Failure and (Re-)Confirmation (4:27–7:7)

1. Reunion of Moses and Aaron and Reception by the Nation (4:27–31)

2. Rejection by Pharaoh (5:1–23)

3. A Patient Reminder of the Lord’s Promises (6:1–8)

4. Reassurance and Preparation (6:9–7:7)

E. The Judgment of the Plagues (7:8–10:29)

1. Initial Confrontation (7:8–13)

2. The Nine Judgments or Plagues (7:14–10:29)

F. Free at Last (11:1–15:21)

1. The Last Judgment or Plague (11:1–10)

2. Deliverance from Death and Preservation by Passover (12:1–30)

a. The Preparation of the People for the Passover (12:1–13)

b. The Instructions for the Feast of Unleavened Bread (12:14–20)

c. The Passover Executed (12:21–22, 28)

d. The Promise of the Passover and the Promise to the Nation (12:23–27)

e. The Last Judgment Executed: The Death of the Firstborn (12:29–30)

3. The Exodus Itself (12:31–39)

a. Pharaoh Relented in Sorrow (12:31–32)

b. The Nation Departed in Haste (12:33–39)

4. Summary: The Years of Bondage (12:40–41)

5. Instructions Regarding the Foreigner and Sojourner and the Passover (12:42–51)

6. The Consecration of the Firstborn (13:1–16)

7. Deliverance through the Sea (13:17–14:31)

a. Phase One: The Lord Led the People (13:17–22)

b. Phase Two: Pharaoh Chased the People (14:1–12)

c. Phase Three: The Lord Preserved the People (14:13–31)

8. Praise for Deliverance and Preservation: The Song of Moses (15:1–21)

G. The Journey from the Sea to Sinai, Part One (15:22–17:7)

H. The Journey from the Sea to Sinai, Part Two (17:8–18:27)

1. War with Amalek (17:8–16)

2. Reunion with and Advice from Jethro (18:1–27)

II. The Law and the Tabernacle (19:1–40:38)

A. Preparation of the People to Receive the Law (19:1–25)

1. The People Accept and Commit to the Covenant (19:1–8)

2. The People Demonstrate Consecration (19:9–25)

a. The Place of the Lord (19:9)

b. The Place of the People (19:10–15)

c. The Place of the Priests (19:22)

d. The Appearance of the Lord (19:16–20)

e. The Warning of the Lord (19:21, 23–25)

B. Presentation of the Decalogue to the People (20:1–17)

1. Preamble (20:1–2)

2. The First Tablet Commanded the People to Honor the Lord (20:3–11)

a. No Other Gods (20:3)

b. No Idols (20:4–6)

c. No Swearing (20:7)

d. Sabbath Observance (20:8–11)

3. The Second Tablet Commanded the People to Honor Others (20:12–17)

a. Honor Parents (20:12)

b. Do Not Murder (20:13)

c. Do Not Commit Adultery (20:14)

d. Do Not Steal (20:15)

e. Do Not Lie (20:16)

f. Do Not Covet (20:17)

C. The People Respond with Devotion, Fear, and Worship (20:18–26)

D. Application of the Law: Living the Life of Faithfulness (21:1–23:19)

1. Laws Pertaining to Slavery (21:1–11)

a. Male Slaves (21:1–6)

b. Regarding Female Slaves (21:7–11)

2. Laws Pertaining to Personal Injury (21:12–36)

3. Laws Pertaining to Personal Property (22:1–15)

4. Laws Pertaining to Personal Integrity (22:16–23:9)

5. Laws Pertaining to Worship (23:10–19)

E. Plans for the Conquest of the Land (23:20–33)

F. The Ratification of the Covenant (24:1–18)

1. The Approach to the Lord (24:1–11)

2. Moses on the Mountain (24:12–18)

G. Intructions on The Tabernacle, Its Builders, and the Priests (25:1–27:21; 30:1–21; 31:18; 35:1–38:31)

Excursus: Introduction to the Tabernacle

Focal Point for the Nation

Theories of Origin

Terms to Designate the Tabernacle

Purposes of the Tabernacle

1. The Initial Instructions (25:1–9)

a. The Contributions (25:1–8; 30:11–16; 35:4–9; 38:21–39:1)

b. The Lord’s Pattern (25:9)

2. The Ark of the Covenant: Symbol the Lord’s Holy Presence (25:10–16; 26:34; 37:1–5)

3. The Mercy Seat: Symbol of Propitiation (25:17–22; 37:6–9)

4. The Table of Showbread: Symbol of Physical Provision (25:23–30; 26:25; 37:10–15)

5. The Golden Lampstand: Symbol of Spiritual Provision (25:31–40; 26:35; 37:17–24)

6. The Tabernacle Itself: Symbol of God’s Personal Presence (26:1–30)

7. The Veil and Screen: Symbol of God’s "Hiddenness" (26:31–37)

8. The Bronze Altar: Symbol of the Need for a Sacrifice for Sin (27:1–8; 38:1–7)

9. The Court: Symbol of Separation (27:9–20; 38:9–20)

10. The Priests of the Tabernacle (27:21–29:46)

a. Priestly Functions (27:21–28:1)

b. Priestly Garments (28:2–43; 39:1–31)

c. The Consecration of the Priests (29:1–46)

11. The Altar of Incense: Symbol of Prayer and Intercession (30:1–10; 37:25–29)

12. The Census (30:11–16)

13. The Bronze Laver: Symbol of Cleansing (30:17–21; 38:8; 40:30–32)

14. The Anointing Oil and Incense: Symbol of Consecration (30:22–38)

15. The Builders of the Tabernacle (31:1–11; 35:30–35; 36:1–2)

16. Sabbath Reminder (31:12–18; 35:1–3)

H. Apostasy and Aftermath (32:1–34:35)

1. The Golden Calf (32:1–29)

a. The Folly of Aaron and the People (32:1–6)

b. Anger and Intercession (32:7–14)

c. Confrontation: Moses Against Aaron and the People (32:15–29)

(1) A "Heavy" Descent (32:15–18)

(2) A "Hot" Confrontation (32:19–20)

(3) A "Heated" Conversation, Moses vs. Aaron (32:21–24)

(4) A Harsh Division (32:25–29)

2. Five Scenes of Intercession and Intimacy, Moses and the Lord (32:30–33:23)

a. Scene One: A Selfless Offer (32:30–35)

b. Scene Two: A Hopeful and Sorrowful Word (33:1–6)

c. Scene Three: A Separate Arrangement (33:7–11)

d. Scene Four: An Intimate Conversation (33:12–17)

e. Scene Five: A Glorious Encounter (33:18–23)

3. Restoration and Renewal (34:1–35)

a. Restoration of the Two Tablets (34:1–9)

b. Renewal of the Covenant (34:10–26)

c. Summary and Transition (34:27–29)

d. Epilogue: Moses’ Face Shines (34:29–35)

I. The Instructions for the Tabernacle Are Repeated (35:1–39:43)

1. The Sabbath Reminder (35:1–3)

2. The Contributions (35:4–9)

3. The Workmen and Their Work (35:10–19)

4. The Workmen and the Contributions (35:20–36:7)

5. The Construction Continued (36:8–37:29)

a. The Curtains, the Boards, the Veil, the Screen (36:8–38)

b. The Ark, the Mercy Seat, the Table, the Lampstand, the Altar of Incense (37:1–29)

6. The Bronze Altar, the Laver, the Courtyard (38:1–20)

7. The Inventory (38:21–39:1)

8. The Priestly Garments: Ephod, Breastpiece, Robe, Tunics, Turban (39:2–31)

9. Summary: Tabernacle Completed (39:32–43)

J. The Construction and Erection of the Tabernacle (40:1–33)

K. The Occupation of the Tabernacle (40:34–38)

COMMENTARY ON EXODUS

I. Redemption: The Lord Delivered the People of Israel from Bondage in Egypt (1:1–18:27)

The narrative begins with the account of how God provided Israel with deliverance/liberation from bondage in Egypt, preservation/protection in the exodus from Egypt, and guidance/provision on the journey to Sinai.

A. How the Bondage Began (1:1–22)

The explanation of how the children of Israel came to be in bondage in Egypt is brief and to the point. This section reveals how the nation came to need deliverance.

1. Opening Genealogy (1:1–7)

1:1–7. In the brief opening paragraph of Exodus the author has tied the narrative of Genesis to the narrative of Exodus with a genealogy of the sons of Jacob (cf. Gn 46:8–27), highlighting the special status of Joseph. He is mentioned last in the list and his death is singled out. The Lord’s providence was evident in His preservation of Joseph personally and was the means of the preservation of the family of Jacob and thus of the nation of Israel (see Gn 37; 39–47; 50:20). That family that came to Egypt amounted to just over seventy persons (cf. Gn 46:27; Dt 10:22; Ac 7:14; seventy came to Egypt with Jacob, and Joseph’s family was already there). That family had, in fulfillment of the promises of the Lord to Abraham (Gn 15:5, 13; 17:6) and Jacob (35:11–12) become a nation. They had increased greatly, and multiplied in number (1:7; see Nm 1:46) and potentially in power. These few verses summarize a period of over four hundred years.

2. The Oppression Begins (1:8–14)

1:8–14. After so many years the memory of, and gratitude for, the ministry of Joseph and his service to Egypt was lost. A new king (probably a ruler in the Hyksos period; see Introduction: Date) arose over Egypt (1:8). The expression arose over may be meant to convey something more like "arose against," thus indicating that this was not the normal succession but a takeover by a hostile power (cf. Davis, Moses and the Gods, 53). This king recognized that the remarkable growth and prosperity of the children of Israel (no longer a mere family but now a nation) was an internal threat to his administration of Egypt and/or a potential ally of any invading army. His response, to diminish the threat, was to initiate a program of oppression and affliction by enslaving the children of Israel. Perhaps he intended to deplete the population of Israel or simply meant to keep their growth in check while keeping them as subjects and slaves. The policy failed, however, because the more they were afflicted, the faster the population of Israel increased and the further they spread out. Still, the pharaoh pursued his shortsighted and oppressive policy with increased vigor.

Since the bondage lasted over four hundred years (12:40; cf. Gn 15:13; Ac 7:6) it is obvious that there was a gap of time between the initial bondage of the new king and the continued systematic oppression indicated in 1:13. Here it is the Egyptians (see Introduction: Date) who devised the manner of oppression by means of brickmaking and labors in the field (1:14).

3. The Oppression Continues (1:15–22)

1:15–22. When the policy of oppression failed to reduce the numbers of the sons of Israel or to diminish the perceived threat against them, the Egyptians initiated a policy of genocide (and not for the last time would the descendants of Israel face such a horror). Essentially the king of Egypt (probably Thutmose I, see Introduction: Date) instructed the Hebrew midwives Shiphrah and Puah to murder all the male children born to the Hebrew women. These two women were probably the acknowledged, if unofficial, authorities over the vocation of midwifery, and all the Hebrew midwives were to carry out the king’s orders. These brave and faithful women are said to have feared God, and no doubt they believed that children were the gift of God (Ps 127:3) and the killing of such was simply murder. They knew the principle that when the laws of man are in conflict with the commandments and will of God the faithful must obey God rather than men (Ac 5:29). And so these godly women defied the king’s orders, and the children of Israel continued to thrive and multiply.

When asked for an explanation for the ongoing male births, the midwives told the king that the Hebrew women were vigorous and gave birth without their intervention, which may have been the case but highly unlikely. It is possible that the midwives were blessed, not for their less-than-forthright answer to the king’s inquiry but because they feared God. Another possibility is that they chose the greater good (life-saving over truth-telling), and were thus exempt from the requirement of telling the truth. This would be similar to a surgeon performing life-saving surgery being exempt from laws forbidding cutting someone with a sharp instrument, or the exemption for traffic laws that an ambulance driver receives when rushing a coronary victim through a red light in order to get him to the hospital. In this case, the midwives were blessed for their lifesaving and their less-than-forthright answer.

In frustration the king simply ordered all his people (1:22) to take an active role to ensure the death of the newborn male children of the Hebrews.

B. Moses: Early Life and Calling (2:1–22)

The narrative proceeds to tell how Moses came to be God’s instrument to deliver the children of Israel from bondage in Egypt: this section chronicles the life of the instrument of Israel’s deliverance.

1. Moses’ Mother Endeavors to Save Her Son (2:1–4)

2:1–4. The narrative quickly moves from the menace of Pharaoh’s command to the nation as a whole to the peril it posed for one Levite couple (Amram and Jochebed, cf. Ex 6:20) and their newborn son. The description that the child was beautiful indicates that even in infancy this child was recognized as exceptional (cf. Ac 7:20; Heb 11:23). The tenderness of a mother’s love led to desperate measures to preserve Moses’ life. In terms reminiscent of the ark of Noah (which preserved life), Moses was placed in a papyrus basket covered with tar and pitch (cf. Gn 6:14) and set afloat on the Nile (in literal, if not intentional, obedience to Pharaoh’s command; cf. 1:22). This ark was placed out of the current of the river (among the reeds) and watched over by his sister (Miriam, cf. Ex 15:20; Nm 26:59).

2. Moses’ Life Is Preserved by Pharaoh’s Daughter (2:5–10)

2:5–10. Either by the design of Moses’ mother or simply God’s providence, the ark was placed near the spot where a royal princess came down to bathe at the Nile (2:5). In short order, the ark and child were discovered and the crying infant elicited the princess’ pity, even though she recognized that this baby was one of the Hebrews’ children. Sensing the princess’ intention to preserve this child, Moses’ sister stepped forward with a bold proposal to find a wet-nurse to care for the infant, a proposal that was quickly accepted. By this unlikely means Moses’ life was spared and he was reunited with his birth mother (who was paid for the privilege to nurse him).

As the son of the Egyptian princess, he received a royal upbringing (and likely a high level Egyptian education, Ac 7:22) but being cared for by his birth-mother, he would also have understood his heritage as a Hebrew. His name, Moses, perhaps related to contemporary Egyptian names (Ahmose, Thutmose), was a pun drawn from his being "drawn out" (the meaning of a Hb. verb mashah) of the water. It is unlikely that an Egyptian princess would have made a pun using a Hebrew verb; the name was likely given or suggested by Moses’ birth mother. God’s providential care was clearly evident. Just as God was faithful in protecting Moses, this episode would encourage the Israelite readers of Moses’ book that He would be faithful to them as they would fight to enter and subdue the promised land in the years to come.

3. Moses’ Failure (2:11–15a)

2:11–15a. Moses’ first attempt to deliver and preserve his brethren was inept and an utter failure. Many years (about forty, Ac 7:23) passed and the narrative moves to Moses the man. Apparently, while still living in the privileged position as the son of an Egyptian princess, he was nevertheless aware of his Hebrew lineage and knew them as his brethren (2:11; noted twice in the text). No doubt their hard labors, in contrast to his life of relative privilege, aroused an acute sense for injustice in Moses (cf. Heb 11:25). On one occasion, Moses saw an Egyptian abusing a Hebrew and his sense of injustice was provoked. This incited a misguided and rash act—Moses killed the Egyptian. That he had looked around to assure himself that he would not be seen and that he hid the body in the sand (2:12) shows that Moses himself knew this act was wrong. If Moses expected that his brethren would applaud his act and protect his identity he was mistaken. On the next day Moses witnessed two Hebrews fighting and sought to intervene, only to be rebuffed and threatened with exposure. The offenders’ comment (as you killed the Egyptian, 2:14) was a not-so-subtle threat letting Moses know the matter has become known; and indeed when Pharaoh heard of the offense he tried to kill Moses (2:15).

4. Moses’ Sojourn in Midian (2:15b–22)

2:15b–22. Once again the narrative moves quickly through the story of Moses’ sojourn and subsequent marriage. God’s providential plan for preparing Moses to guide the people of Israel led to an extended sojourn (of about forty years, cf. Ac 7:29–30) in the desert region of Midian. There, his sense for injustice once again led him to intervene in a dispute between the daughters of the priest of Midian (Reuel, Jethro, Ex 3:1) and some shepherds at the well for watering livestock (2:17). This act of chivalry led to his marriage (to Zipporah), a family (son, Gershom), and a life as a shepherd. "The long years in the desert were not wasted but times of further maturity and reflection in the things of God (cf. Ac 7:29ff.)" (Davis, Moses and the Gods, 57).

C. The Call of Moses: Reluctance and Compulsion (2:23–4:26)

1. The Nation’s Bondage Recalled (2:23–25)

2:23–25. While the sons of Israel continued to suffer in bondage, Moses was being prepared; even with a change of regime in Egypt, the need for his service grew even more acute. The bondage of the nation was severe; but God heard Israel’s cries and He remembered His covenant (2:24) with the patriarchs. When He took notice of them (2:25), He would soon send them a man to liberate and lead them. The point of this brief note in 2:23–25 is to place Israel’s need to be freed from bondage in the context of Moses’ call. While the nation suffered the Lord was preparing for their deliverance. They were completely unaware that, in an unknown place in an unimaginable way, the Lord was calling an unexpected man to be their deliverer. God’s providence in the preparation of Moses may have served as an encouragement for Moses’ readers. During the oppression in Egypt, the Jewish people could not have anticipated how God would work to prepare a leader for them, but He was working. In the same way, He would undertake for them in equally surprising ways to conquer the land when they would enter it.

2. Moses Called to the Burning Bush (3:1–9)

3:1–6. God called Moses while Moses was engaged in the mundane business of tending his father-in-law’s flock, probably in a location he had been to many times before during these forty years away from Egypt (see Ac 7:23 and Ex 7:7). It was at Horeb (3:1; another name for Sinai; cf. Ex 19:11), the mountain of God, that the Lord called Moses, and it was a calling as unexpected to Moses as it was inescapable in God’s eternal purposes. Here a brilliant manifestation of God appeared (cf. Gn 15:17; Ex 13:21; 40:34; 1Ki 8:11), the burning bush, to signify that the Lord (here in the form of the angel of the Lord) was present (3:2). The expression angel of the Lord may also be translated "messenger of the Lord" leading some to conclude that this is a supernatural being ("a special divine messenger from the court of heaven … representing the Lord" [Youngblood, Exodus, 32]) but not the Lord Himself. Others argue, however, that the entity here "is unlikely to be a supernatural being distinct from God" (Victor P. Hamilton, Exodus: An Exegetical Commentary [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2011], 46). The "angel/messenger" of the Lord appears in a number of biblical narratives (cf. Gn 16:7, 9, 11; 22:11, 15; 31:11; 48:16; Jdg 6:11; 13:13, 15, 16), and a number of "these references speak of angel/God/Lord as if interchangeable and undistinguishable, reinforcing the idea that the Lord himself is the angel and the angel is the Lord himself" (Hamilton, Exodus, 46). Some have gone further and suggested that the "angel of the Lord" is a pre-incarnate manifestation of Jesus Christ. Since "no man has seen God at any time" and since Jesus Christ is the Revealer of the Father (cf. Jn 1:18; 12:45; 14:9), they argue, the theophanies (visible manifestations of God) in the OT are actually manifestations of the pre-incarnate Christ. (See comments on Gn 32:24–25).

The angel established the solemnity and sacredness of the setting and of the moment by a solemn address, Moses, Moses, and a stern command to remove his sandals (being filthy) because the place was made holy by the presence of the Lord (3:5). The Lord’s self-identification as the God of the patriarchs signified that Moses’ calling was to be in service to the Lord’s promise (cf. Gn 12:1–3; 15:13–16). What began as mere curiosity (3:3) was turned to reverential fear (3:6b) by the awesome encounter with God.

3:7–9. Immediately the Lord turned Moses’ attention to the affliction of My people who are in Egypt (3:7). God informed Moses that He was well aware of their misery (cf. 2:24–25), their cry caused by their sufferings. Moreover, He was about to fulfill His promise to Abraham and bring them up from Egypt to the land of promise, the land of blessing, flowing with milk and honey (3:8). The land was clearly demarcated in the promise He had made to Abraham in Gn 15. A comparison of the list of Canaanite names here with those in Gn 15:19–21 demonstrates the continuity of this narrative with that of Genesis and the abiding validity of the promise God made to Abraham.

Here in Exodus as there in Genesis the intent of the list of these names is to specify the actual geography—the land, the "dirt"—where the promise to Abraham was to be fulfilled. Since both Abraham and Moses would have been thinking of an actual physical land as God reiterated His promise, it is obvious that nothing less than the actual physical land could be or will be the fulfillment of this promise. It should also be noted that the list in both contexts ends with the Jebusites (cf. 3:17; 13:5; 23:23), the Canaanite tribe that David later displaced in order to establish his capital at Jerusalem (cf. 2Sm 5:6ff.). The defeat of the Jebusites and the establishment of Jerusalem as the nation’s (everlasting) capital is foreshadowed in this seemingly pedantic list of Canaanite names. By reiterating this list to Moses—first given to Abraham and looking forward to David—the Lord tied together several stages of the history of His promise-people.

Lastly, the oppression of the nation by the Egyptians was noted again, not simply to say the Lord was aware but to indicate that it was about to come to an end.

3. Moses Commissioned by "I AM WHO I AM" (3:10–4:17)

In the light of the cry of Israel and the intense oppression by the Egyptians, Moses was told that he was chosen to be the human instrument to accomplish God’s deliverance of the nation (My people). Immediately Moses objected to this call and in the course of this encounter he offered several more objections. The Lord answered each objection consecutively, until Moses reluctantly and humbly accepted the task to which God was calling him.

a. Moses’ First Objection (3:10–12)

3:10–12. In this first objection Moses feigns personal insignificance and inadequacy; he displayed a false humility (3:11). God’s answer essentially accepted his argument, Moses was, in and of himself, insignificant and inadequate; but with the Lord’s presence—I will be with you—His power, and His purpose, Moses could not fail. Moses would be sufficient and adequate for the call with a sufficiency and adequacy supplied by God Himself. Only by obeying the call and seeing the sign of an accomplished work, when a redeemed nation will be gathered for worship on this very mountain (3:12) could Moses accomplish the monumental task the Lord set before him. God unfolded to Moses what would come about, and the role Moses would play in it. Since these events did transpire as God predicted, the original audience, Israelites who were about to enter the land, would do battle to take the land. They would be encouraged that God not only knew what would happen, but promised that they would succeed, just as He did for Moses.

b. Moses’ Second Objection (3:13–17)

3:13–17. This objection is rather odd: the Lord had identified Himself to Moses as the God of the patriarchs (cf. 3:6), the fathers. Here Moses seems to be suggesting that if he returned and told the sons of Israel that this God had authorized him they would ask for His name. Moses was implying that if he could not supply them with a name this would somehow undermine his authority with them. In the majestic and awesome response, God gave one of the most important expressions of His self-revelation recorded in Scripture. He identified Himself as I AM WHO I AM and informed Moses that he should simply say to the people I AM has sent me to you (3:14).

The name I AM is a literal translation of first person singular of the Hebrew verb ‘ehyeh ("I am"); the third person singular of this verb is transliterated yehweh ("he is"). This latter term is taken as the name of God ("Yahweh") and is rendered in most English translations as "Lord"; the combination of these four letters (in Hb. YHWH) is called the "tetragrammaton" (the four letter name of God). This name is dense with implications about the nature and being of God—He is self-existent, affirming that God is uncaused and depends on no other source for His existence—and rich with theological meaning—as the memorial-name this name becomes the name identifying God as the deity who makes covenant promises and keeps them to all generations (3:15). But the immediate significance for Moses and the nation was readily apparent. This name declared that the God who IS (exists), the God who IS God (the living God, the real God), the God upon whose existence all that exists depends (cf. Jn 1:1–2; Col 1:17) is none other than the God who spoke to and made promises to the patriarchs (3:15).

In short, His name and His association with the patriarchs would mean to the nation that their God was the only God, the true God (cf. Is 44:6–8), and He had the power and authority as God and the interest and commitment to them as the God of the fathers (the patriarchs, Abraham, "Isaac," and Jacob) to bring about their deliverance from bondage. God’s explanation to Moses reiterated that His concern for them was not merely because of their sufferings but that He intended to fulfill His promise concerning the land, a promise that may have provided considerable encouragement for the people as they were preparing to enter the land. In terms reminiscent of the covenant promise to Abram in Gn 15, the Lord specified the location (based on the tribal identities of the Canaanite tribes) and fruitfulness of the land (3:17) to which He would deliver the nation.

c. A Preview of Coming Events (3:18–22)

3:18–22. God took this moment to provide Moses with a brief overview of the events of the exodus that were soon to unfold. He assured Moses that while the elders of Israel would pay heed to Moses’ words, the king of Egypt would not (3:19). Even a modest request for the opportunity to worship and sacrifice to the Lord, the God of the Hebrews, would be rejected. Thus, only by force, under compulsion and by the miracle power of My hand, My miracles (the coming plagues), will the king of Egypt let them go. And in the process the people will not go empty-handed from Egypt but the Egyptians themselves will provide every household (every woman) with wealth and provisions (perhaps like a bride) to have them leave after the devastation of the plagues; thus they would plunder the Egyptians (3:22). Abraham’s sojourn in Egypt foreshadowed the events described here (see comments at Gn 12:10–20). This overview was given to encourage Moses, and later the nation, that the Lord’s plan will unfold exactly as He had foretold. As they saw His previous promises fulfilled as He said, they could trust Him to fulfill His promises to enable them to conquer the land.

d. Three Signs and a Spokesman for Moses (4:1–17)

4:1–9. Moses was still not ready to commit himself to God’s calling. His third objection was that he lacked the credentials necessary to authenticate that the Lord had indeed appeared to him (4:1). To overcome this objection, Moses was given three signs (cf. Dt 13:1–3). First, his own shepherd’s staff would be enabled to become a serpent and then a staff again (4:2–5). That this was not a mere illusion of a snake but a real snake is proven by the note that when Moses first performed this sign even he fled from it (4:3). Also, Moses picked the serpent up by the tail (4:4; the usual manner is to pick up dangerous snakes is by the neck to avoid the fangs) to demonstrate total mastery over the creature. The symbolism here is fairly clear. The serpent had been an instrument of Satan (cf. Gn 3:1, 14), hence an emblem of evil and was used often in Egyptian iconography and religion. Moses’ mastery over the serpent indicated the Lord’s mastery over Satan and the gods of Egypt. This point will be made even more clearly in the coming judgments on the Egyptians; cf. chaps. 7–12.

For the second sign, Moses’ hand could be turned leprous and then restored (4:6–7). Kaiser notes that "leprosy," or Hansen’s disease, was known in antiquity. But leprosy in the Bible apparently covered cases of psoriasis, vitiligo, ringworm and other skin ailments (Kaiser, "Exodus," 326). For the purposes of the sign the disease had to be advanced and then instantly cured. Living in the dry and insect-infested environment they did, the Egyptians were constantly afflicted with skin ailments and they were scrupulous about skin hygiene. This sign would have at first horrified them and then intrigued them. This kind of power spoke directly to the existential realities of their daily lives.

In the third sign Moses was to take water from the Nile which when poured out on dry ground was turned to blood (4:8–9). This sign proved the power of the Lord over one of the most sacred elements of Egyptian religion and obviously had the potential to affect the most vital aspect of Egyptian daily life, water from the Nile River.

The overall point of these particular signs was obviously the supernatural power they demonstrated. These wonders were beyond the power of a mere man and verified that the message Moses spoke was, like these wonders, from the Lord (cf. 1Ki 17:24). Beyond that they demonstrated the power of God over elements that the Egyptians held sacred and over things they considered were under the authority of their gods. And just as God would overcome Moses’ reluctance to confront the Egyptians with His promises and power, so also the narrative might encourage any of the Jewish people who were reluctant in the face of the daunting prospects of subduing the promised land.

4:10–17. Even after these amazing signs are given to him, Moses had two more objections. In the fourth of his objections he protested that he had never been eloquent and that he was slow of speech and slow of tongue (4:10). God responded that since He made man’s mouth and gave men the abilities of their senses (4:11) He could overcome any deficiencies in His chosen messenger. In a final objection Moses bluntly asked God to send someone else (4:13). With His patience at an end, the anger of the Lord burned (4:14a). However, He was still gracious to His chosen servant, and the Lord answered the fourth objection by giving Moses a spokesman, Aaron, his brother, to speak for him (4:15–16). In His providence Aaron was already on his way to meet Moses (4:14c). Thus, Moses was to take his hand, his staff, the signs, and himself and "Go!"

4. Transitions (4:18–26)

4:18–23. Between Moses’ call and his first confrontation with Pharaoh a series of transitional events occurred. Moses needed to transition from his temporal obligations and prepare for the climatic confrontation with Pharaoh. Moses had not been simply sitting around waiting for the Lord’s call. He had an active home life and obligations that needed to be addressed before he was ready to devote himself to God’s calling. First, in an act of deference and respect, Moses took leave of his father-in-law, Jethro (v. 18). The Lord then reassured him that those who sought his life were now dead. Then he packed up his family, his wife and his sons (Gershom, cf. 2:22; Eliezer, cf. 18:5), on a donkey (indicating that he was traveling light), took the symbol of his calling, the staff of God in his hand (for reassurance), and left for Egypt. Once again the Lord warned Moses that he should be prepared to use all the signs given to him but that Pharaoh would be obstinate (on the meaning of harden his heart, see 7:3) and refuse to comply with the demand to let the people go. Here the Lord called Israel His firstborn son (4:22), an indication of priority and preferred status. Because Pharaoh had afflicted the Lord’s firstborn he would suffer the death of his firstborn, foreshadowing the last plague on Egypt.

4:24–26. Then a curious event took place that involved Moses’ son. The man of God cannot be less than dutiful and thorough in his obedience to the Lord in all things and apparently, Moses had failed to circumcise one of his sons. For this, the Lord disciplined him, and sought to put him (Moses) to death (4:24). The death threat was probably some life-threatening illness but the exact nature is not clear. It seems that Zipporah then took it upon herself to perform the rite, even though she found the act repulsive, likely because of her non-Israelite origins. She flung the baby’s foreskin at Moses’ feet (possibly a euphemism for genitals but not necessarily) and called him a bridegroom of blood. In saying this, Zipporah is declaring that Moses is now her bridegroom for a second time. Umberto Cassuto explains that she was saying, "I have delivered you from death, and your return to life makes you my bridegroom a second time, this time my blood bridegroom, a bridegroom acquired through blood" (Umberto Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Exodus, 3rd ed. [Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1967], 60).

The significance of this passage is twofold. First, it demonstrated that if Moses was to be the spokesman for the covenant-keeping God of Abraham, he needed to keep the provisions of the covenant (Gn 17:9–22). Second, it foreshadowed the requirement that those participating in the Passover were required to be circumcised (Ex 12:43–48). It may have been at this time that Moses’ family returned to Midian (see comment on 18:2).

D. The Return of Moses: Failure and (Re-)Confirmation (4:27–7:7)

While the reunion of Moses and Aaron brought them joy, and their initial report brought the nation joy, the first encounter with Pharaoh brought the nation increased hardship and affliction. Already the Lord would have to reassure a discouraged and distracted leader.

1. Reunion of Moses and Aaron and Reception by the Nation (4:27–31)

4:27–31. Aaron had been sent by the Lord to meet Moses (cf. 4:14), and the two brothers were reunited at the mountain of God (4:27). After relating to Aaron all that God had told him, Moses proceeded with Aaron to Egypt and assembled all the elders and sons of Israel and showed them the signs and informed them of God’s intention to free them from their affliction. They believed and worshiped (4:31).

2. Rejection by Pharaoh (5:1–23)

5:1–23. The hardhearted resistance of Pharaoh soon dissipated the initial joy of the people over the news of God’s intention to free the nation from bondage. Moses’ initial request to Pharaoh was instantly and harshly rebuffed. When Pharaoh said, I do not know the Lord (5:2), he probably did not mean he had no knowledge of Israel’s God but that their God was not one he acknowledged, worshiped, or served. Moses and Aaron made a milder request and asked to be released merely for a respite to worship. Perhaps Moses and Aaron were testing Pharaoh or attempting to gauge how far he would be willing to negotiate. Perhaps they intended to "work up" from this mild request to the bolder demand to let the people go. They argued that they made this plea in fear of divine judgment, otherwise He will fall upon us (5:3).

This was an odd argument because the Lord had said nothing like this in any of His previous instructions to Moses. In any case, Pharaoh rebuffed even this milder request. The exchange here seems to indicate that Moses and Aaron were negotiating with Pharaoh rather than forthrightly speaking exactly what God had commanded them (cf. 7:2). Nor did Moses perform the sign that had been given to him as the Lord had directed him (cf. 4:21; 7:10).

Pharaoh then accused Moses of catering to the laziness of the people (5:4; cf. 5:8, 17), and he even increased the intensity of their labors and the severity of their treatment by the taskmasters (5:6–9). Straw served as a binding and strengthening agent for the clay used to make the bricks, and was apparently provided for them. But at this point the responsibility for gathering the straw was forced upon them. Yet the quota of bricks was to remain the same as before. In order to fulfill this demand the people were forced to spend more time and effort gathering stubble for straw, that is, the remnants of the stalks left in the fields after the harvest. To compel compliance for this increased labor, even the foremen of the sons of Israel (5:15a) (probably Israelite man who served as "lead men" or level of foremen under the taskmasters and foremen of the Egyptians) were beaten (5:14). Perhaps thinking that the taskmasters were exceeding their authority and that they were being unreasonable, the Israelite foremen appealed to Pharaoh, Why do you deal this way with your servants? (5:15b). Pharaoh’s response was an even more direct accusation that they were lazy and a reiteration of the directive that they were to produce their quota of bricks (5:17–18) while also gathering straw. This left the foreman despondent and upon meeting Moses and Aaron they accused them of bringing this trouble upon them; you have made us odious ("you have made us stink") and you have put a sword into their hand ("you have made it even easier for them to destroy us") (5:20–21).

Moses himself succumbed to this despondency and complained, Oh Lord, why? (Why this? Why me?) (5:22). Evidently, Moses had forgotten the Lord had told him to expect this reaction from Pharaoh (cf. 4:21).

3. A Patient Reminder of the Lord’s Promises (6:1–8)

6:1–8. For Moses and the people, Pharaoh’s rejection of Moses’ request was a disheartening setback. The people’s quick reversal of attitude, from the joy of Moses’ revelation of God’s intent to deliver them (cf. 4:31) to the dejection of the foremen, led to a despondent Moses. So God once again patiently reassured him. In a passage of rich theological importance, He reminded Moses I am the Lord (6:2, 6), the God who makes promises and keeps them (cf. 3:14–15). He reminded Moses that this deliverance was something He would do (I will; 6:1, 6 [3x], 7 [2x], 8 [2x]). He reminded Moses of the covenant promise made to the patriarchs (6:4, 5, 8). He reminded Moses of His compassion and concern over their burdens and bondage (6:7, 9). When the Lord said that the patriarchs knew Him as God Almighty but that by the name Lord He had not made [Himself] known to them (6:3), He could not have meant that they had never heard or learned of that name, for they surely had (cf. Gn 4:26; 9:26; 12:8; 22:14; 24:12).

The idea here is the patriarchs knew of the God who made the promise (of a great nation) but this generation, Moses’ generation and the generation that conducted the conquest, would know Him as the God who keeps the promise (of making them a great nation and leading them out of bondage, cf. Gn 15:13–14). The patriarchs knew Him as a promise-making God. Moses’s people will know Him as a promise-keeping God and they will say He is: the Lord your God, who brought [us] out of bondage (6:7). And this God would fulfill the promise by giving this people the land of promise (6:4 [2x]; 8).

4. Reassurance and Preparation (6:9–7:7)

6:9–7:7. Such was the disappointment over the initial failure to move Pharaoh to release the nation that the people were not reassured even by what the Lord had told Moses (6:9), and Moses again expressed his lack of confidence in his speaking ability (6:12b, 30). Two arguments are given for reassurance that Moses was indeed the man for the job: first, a selective genealogy is given that records Moses’ and Aaron’s hereditary and familial background. "The Hebrew method of identification was to give a genealogy" (Alan R. Cole, Exodus, TOTC [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1973], 93). As the ones who are called by God to confront Pharaoh with the demand for release of the nation, Moses and Aaron had to be legitimate spokesmen for the nation—and for that they had to be part of the nation—as this genealogy attests. The charge to Moses and Aaron (6:13, and 6:28–29) brackets the genealogy.

Second, God simply and firmly reminded Moses and Aaron of three facts. First, they have been called by God for this task and all they were required to do was speak all that I command you (7:2). Second, the resistance of Pharaoh was not only to be expected but was in fact a part of the plan. And third, the aim of all this was to demonstrate that I am the Lord (6:29; 7:5). The use of weak (and aged, 7:7) instruments (i.e., Moses and Aaron) and the resistance of the most powerful monarch on earth at the time would make it clear to all that the deliverance to come would be accomplished not by Moses’ persuasive ability or by the nation’s own might or as the result of the weakness of the king but by the compassion and awesome power of God in fulfillment of His promises. So it would be when the weak instrument consisting of the wilderness generation would face its opponents when entering the land.

The matter of the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart (7:3) is a question that has been debated at length (see the commentary on Rm 9:17–18), and often comes down to a debate over the sovereignty of God and the question of human free will. It should be noted that the author of Exodus makes no attempt to reconcile the issue. It is true that God hardened Pharaoh’s heart (4:21; 7:3; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8, 17) and it is true that Pharaoh hardened his own heart (7:13, 14, 22; 8:15, 19, 32; 9:7, 34, 35; 13:15). Some have tried to resolve the issue by suggesting that Pharaoh is responsible for hardening his own heart, and God simply determined what He (fore-)knew Pharaoh would do of his own free will. But this will not do since it is clear from 4:21 and here in 7:3 that the hardening was initially and principally the Lord’s doing for His purposes.

This is a classic case of compatibilism, which simply means that the determined plan, purpose, or action of God is compatible with the free act of an agent (in this case Pharaoh). The Lord had determined that Pharaoh’s heart would be hardened—God is sovereign—but Pharaoh, in the act of hardening his own heart, was still free because he was not forced to do something he did not want to do, something that was contrary to his will. As John Feinberg explains, "an action is free even if causally determined so long as the causes are nonconstraining" (John Feinberg, "God Ordains All Things," in Predestination and Free Will: Four Views of Divine Sovereignty and Human Freedom, ed. David Basinger and Randall Basinger [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1986], 24). That is, even though God determined (sovereignly made it happen in such a way that it might legitimately be said that He caused it to happen) that Pharaoh would exhibit a hardened heart, since there were no constraining causes (that is, Pharaoh was not forced to act against what he wanted to do anyway) he was free and thus he is responsible for his own hard heart. Pharaoh freely chose to do exactly what God determined he would do.

The immediate point to be made here in this context is that the Lord Himself makes it clear He is the one behind the hardening and this was for the purpose of manifesting His power, My signs and My wonders in the land of Egypt (7:3b).

E. The Judgment of the Plagues (7:8–10:29)

The narrative proceeds to relate how the children of Israel were finally freed from bondage in Egypt. This section and the next describe the process of Israel’s deliverance by means of the ten judgments. A series of miracles, the "signs and wonders" of which the Lord spoke (7:3), take place. These miracles authorize the Lord’s spokesmen, demonstrate the Lord’s power, humble the Egyptians and Pharaoh, and are directly aimed at the false deities of the pagan Egyptian religion to discredit them, and to unmask them for the false gods they are.

1. Initial Confrontation (7:8–13)

7:8–13. Once again the Lord directed His servants to confront Pharaoh. Here the sign of the rod that became a serpent (cf. 4:2–5), which had been used to authorize Moses and Aaron to the nation (4:30), was employed again in response to Pharaoh’s request to work a miracle (lit., "to show a wonder"). In contrast to the first encounter with Pharaoh (cf. 5:1–3), Moses and Aaron did just as the Lord commanded (cf. 7:6, 10), and Aaron threw down his staff and it became a serpent. Pharaoh attempted to deflect this display of divine authority and power when he called on his wise men, sorcerers, and magicians (officials and practitioners of Egyptian religion; cf. 2Ti 3:8) to employ their secret arts (that is, occultic and demonically empowered practices; cf. Rv 16:14) to mimic the sign either by sleight of hand, by illusion such as the physical manipulation of an actual snake, or by an actual supernatural event empowered by Satan and demons (cf. 2Co 11:13–14; 1Ti 4:1). However, the superior power of the Lord was quickly revealed when Aaron’s staff/serpent swallowed up the staffs/serpents of the Egyptian sorcerers.

In spite of the obviously superior power of the Lord and the preeminence of His servants, Pharaoh’s heart was adamant and he remained implacable. Apparently, Moses and Aaron were not discouraged and despondent at this apparent failure as they had been after the first encounter; perhaps this is because this time they remembered that this had happened just as the Lord had said it would (7:13).

2. The Nine Judgments or Plagues (7:14–10:29)

7:14–10:29. The next encounter with Pharaoh set up the dramatic series of events often referred to as the "ten plagues." A few preliminary points are in order before giving a summary view of the overall flow of these events. First, it seems best to consider the first nine judgments as a unit unto themselves and the final judgment—the death of the firstborn—as the single culminating event, with the Passover, that precipitates the exodus proper. As will be noted, there is a pattern to the first nine events that is not seen in the last event; and the presentation of the last event is much more detailed, indicating that it is distinct from the first nine. Second, the typical designation for these events is "plagues"; but the English term "plague" (as something pertaining to communicable diseases or epidemics) does not fit in that sense with all of these events. The term "judgments" is more descriptive of all of the events and it conveys the divine intent behind them as well. Third, when considering these judgments, especially the first nine, many commentators have attempted to explain them as instances of natural occurrences with perhaps divinely guided timing (cf. 8:23), divinely directed locating (9:4, 6, 26), and in divinely produced proportions. However, it seems best in the light of the timing (viz. Moses’ pronouncements), extent (some were limited to the Egyptians; cf. 8:22; 9:4, 6, 26; 11:7) and evident intent (as attacks on the Egyptian pantheon; see comments below) to take them as genuine miracles (cf. 7:3), manifestations of supernatural divine power that only the Lord God could have accomplished.

This leads to the observation that, fourth, there is an unmistakable theological intent in these events that should not be missed but often is by those who focus more on naturalistic explanations rather than seeing the very point they were originally meant to make: the Lord is the only true God (cf. 40:17). This leads to two final observations: fifth, there was a gradual intensification about these judgments from serious inconvenience to life-threatening disaster; and sixth, though not explicitly indicated, it is clear these judgments were attacks on key features of Egyptian religion and in effect are contests with Egyptian deities (cf. Nm 33:4), designed to prove their impotence and unreality (see the notes under the fourth point below). These tests also are intended to show Pharaoh and his people that the God of the Hebrews, the Lord YHWH, is God.

It is clear that there is a general pattern to these events: First, there was God’s instruction to Moses and Aaron (Then the Lord said to Moses and Aaron: 7:14; 8:1, 16, 20; 9:1, 8, 13; 10:1, 21). Here, at last, Moses and Aaron learned to say and do exactly what God had told them to say and do and thus, in spite of Pharaoh’s recalcitrance, they remained bold, resolute, and determined throughout the unfolding process of these judgments.

Second, in several instances, God, through Moses, made a demand, Let My people go (7:16; 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13; 10:3). This demand is missing in the third, sixth, and ninth events.

Third, in several instances God through Moses gave a warning (7:17–18; 8:2–4, 21; 9:2–3, 14–16; 10:4). Again this warning was missing in the third, sixth, and ninth events. That the demands and warnings were sometimes given indicates that, on the one hand, the Lord was gracious to make His will clear; He wanted Pharaoh to know that His people must be released from bondage and there would be consequences if Pharaoh refused. He did not simply send the judgments and leave Pharaoh wondering why these calamities were happening. In one instance, the Lord even made it clear that the disaster could be avoided if the Egyptians would only seek shelter (cf. 9:18–21). But, on the other hand, in those instances when there was no prior demand and no warning before the judgment fell, the Lord was warning Pharaoh not to be presumptuous. God’s gracious warning was not to be treated lightly or interpreted as a lack of divine resolve. From this it is clear that people should never be presumptuous and expect God will give them time to prepare for the calamity of His judgment (cf. Lk 12:20).

Fourth, often the judgment would be at the expense of a revered god of the Egyptians. Prior to one looming judgment, God described the event: water was to be turned to blood (7:17–18). This was an attack on the god of the Nile, perhaps the river itself, which was considered a deity, or against Hapi, the god of the Nile, or Khnum, god of water and life. The attack could have been to humble Osiris, for whom, in one myth, the Nile was his bloodstream. In 8:3–4 frogs were to invade the land. This was an attack on the god or goddess Heket—or Heqt, wife of Khnum, who was usually represented as a frog. This goddess was in charge of childbirth. In 8:16b gnats (the term is unclear, perhaps "mosquitos") were to cover man, beast, and the land. This was an attack on Geb, god of the land, the dirt itself. In 8:21 flies (lit., "swarms"; the LXX has kynomuia, a type of blood-sucking "dog-fly") were to swarm over the land. This was in effect an attack on all the gods of the land.

In 9:3 the judgment fell upon the livestock; these would die across the land. This was an attack on Apis, a male god of fertility, often represented as a bull, or Hathor, a goddess of the sky who was symbolized in the form of a cow. In 9:9 boils were to break out on man and beast. This was an attack on Qadshu, goddess of sex, indicating the boils were likely sores on the genitals. The irony here is that ash, or soot from a kiln (9:8), was often used by the Egyptians to make soap to keep one clean from such infections, but now would cause them under God’s providence.

Likewise the judgments by hail, locusts, and darkness all were attacks on Egyptian gods. In 9:18–19 fiery hail was to fall on the land. This was an attack on Seth, god of wind and storms. In 10:4–6 locusts were to descend on the land. This was an attack on Serapis, the god of protection of the land; or Isis, the goddess of life associated with flax and making clothes; or Min, a god of fertility and vegetation, who was supposed to be a protector of crops. When darkness overtook the land (10:21–23), several major deities associated with the sun were humbled: Re, Ra, and Amon-Re, and also Aten, Atum, and Horus. These attacks on the Egyptian pantheon would be much more obvious and pointed for the Egyptians living at the time. In effect these were attacks on their entire worldview. Everything that helped them to make sense of the world would crumble around them.

Fifth, a gesture of judgment was performed: for the first (7:20), second (8:6), third (8:17), seventh (9:22), eighth (10:13), and ninth (10:22) judgments this gesture was either Aaron or Moses raising the staff, or both hands, one holding the staff, or just raising one hand. This would not only lend a solemnity to the event but it would make clear that these judgments did not just happen. They descended at the bidding of the spokesmen of the Lord.

Sixth, a description of the event often revealed its impact. The description variously concerned (1) the extent of the judgment (e.g., all the water … was turned to blood, 7:20; through all the land, 7:21; frogs will be everywhere into your bedroom and on your bed … into your kneading bowls, 8:3; all the dust of the earth became gnats through all the land of Egypt, 8:17; insects in all the land of Egypt, 8:24; all the livestock of Egypt died, 9:6; sores on man and beast through all the land of Egypt, 9:9; the hail struck … all the land of Egypt, 9:25; the locusts came up over all the land of Egypt, 10:14; thick darkness in all the land of Egypt, 10:22), (2) the timing of the judgment (e.g., for seven days, 7:25; tomorrow, 8:10; tomorrow this sign will occur, 8:23; a definite time, 9:5; about this time tomorrow, 9:18; for three days, 10:22); and/or (3) the effect of the judgment (e.g., so that the Egyptians could not drink water from the Nile, 7:21; the land was laid waste because of the swarms of insects, 8:24; all the livestock of Egypt died, 9:6; the hail struck every plant of the field and shattered every tree … Now the flax and the barley were ruined, 9:25, 31; the locusts ate every plant of the land and all the fruit of the trees … Thus nothing green was left, 10:15; a darkness that could be felt so they did not see one another, nor did anyone rise from his place for three days, 10:21, 22) In some instances the description noted the protection granted by the Lord to the Hebrews: the flies did not invade Goshen where My people lived, 8:22–23; the cattle of Israel did not die of the pestilence 9:4, 6, 7; in the land of Goshen, where the sons of Israel were, there was no hail, 9:26; but all the sons of Israel had light in their dwellings, 10:23. Those exemptions would have been disconcerting and galling to the proud Egyptians.

Seventh, there was the reaction of the Egyptians to the judgment, beginning with the reaction of Pharaoh. At first Pharaoh was indifferent (with no concern, 7:23), but as the judgments continued to fall and became increasingly severe he was forced to call and re-call Moses and Aaron (e.g., 8:8, 25; 9:27; 10:8, 16, 24) to seek a mitigation of the suffering. Second, there was the reaction of the Egyptian magicians. They were able to reproduce the wonders at first (7:22; 8:7), but then became unable to do so (8:18–19, even confessing that the judgments were the finger of God, 8:19), and finally becoming victims of the judgments themselves (specifically the boils, 9:11). Third, there was the reaction of the servants (likely a reference to the general population); after eight judgments they call upon Pharaoh to comply with Moses’ demands and Let the men go (10:7).

Eighth, as noted, Pharaoh was forced to call Moses and Aaron, and in several instances the king seemed ready to concede. There were instances of Pharaoh (1) asking for Moses’ and Aaron’s intercession (e.g., Entreat the Lord, 8:8; Make supplication for me, 8:28; 9:28; 10:17) and (2) beginning negotiation (e.g. 8:25ff.; 10:8ff.; 10:24ff.). In each of these it is clear the Pharaoh was not bargaining in good faith and even apparent instances of (3) repentance (e.g., 9:27; 10:16). Instead Pharaoh’s repentance was disingenuous at best.

Ninth, there were instances of Moses and Aaron interceding for Pharaoh and Egypt, followed by a mitigation of the judgment granted by the Lord (e.g., 8:12, 30; 9:33; 10:18). This demonstrated the patience and longsuffering of God, and that note should always be added to any discussion of the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart. While it is obvious the Lord is in control and He is inexorably moving Pharaoh to resist and oppose the His demand (see the themes below), it is also true the Lord graciously gives opportunity for, and in a genuine sense desires, true repentance (cf. Ezk 33:11; Mt 23:37).

Tenth, the pattern concludes in each case with the note concerning the reneging of Pharaoh, going back on his promise to let the people go, and the hardening of his heart (7:22; 8:15, 19, 32; 9:7, 12, 34–35; 10:20, 27).

Several themes run through the narrative of the first nine judgments. There is the theme of God’s watch-care over His own. As noted, in several of these judgments the Lord made it clear that He would protect His people from the judgments inflicted on Egypt (cf. 8:22–23a; 9:26; 10:23b). Of course, the best protection would come when the people were taken out of Egypt altogether (similar to what will happen to the Church when it is raptured and escapes the wrath of God during the great tribulation; cf. the comments on 1Th 4:13, 5:11 and Rv 3:10).

A second theme is resistance to the will of the Lord is futile. Pharaoh is made to confront the fundamental reality that the Lord’s will is irresistible. A sub-theme here is that partial repentance and temporary or insincere sorrow for one’s sins against the Lord are unavailing. Only sincere submission is acceptable. Only utter humility before God is appropriate (cf. 10:3).

And that leads to a third, but actually the primary, theme of this narrative, and it is summed up in the majestic declaration: By this you shall know that I am the Lord (7:17a). These events prove that God is sovereign; He is utterly unique (there is no one like the Lord our God, 8:10; there is no one like Me in all the earth, 9:14b); He is active in His creation (I am in the midst of the land, 8:22b); He desires the worship of His people (that they may serve Me, 7:16; 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13; 10:3); He demands the compliance and obedience of all creatures (e.g., every command made to Pharaoh in the narrative).

In the heart of the narrative are two important and revealing passages relating the very words of the Lord to Moses and Aaron. In the first passage in 9:14–16, in words directed to Pharaoh, the Lord explained why He was going about this piecemeal process of delivering the nation from bondage. It was so that you may know that there is no one like Me in all the earth (9:14). Again, this is a direct attack on the paganism and false religion practiced by Pharaoh and the Egyptians. All their gods are impotent and false but these judgments prove that He, the Lord, the God of the Hebrews (9:13) is the only true God. Furthermore, the Lord explained, in effect (9:15) He could have wiped Pharaoh out (cut off from the earth) instantly but He says, I have allowed you to remain (9:16a), it is by divine permission, and grace, and patience, in order [note the divine purpose clause] to show My power and in order to proclaim My Name through all the earth (9:16b; cf. also the comments on Rm 9:17–18). This magnificent purpose is still being fulfilled as the people of God read this account and over thirty-five-hundred years after these events, are still proclaiming to the world His power and His name on account of this amazing demonstration of His grace and power.

In a second key passage, 10:1–2, the Lord revealed specifically that this series of events was to be told to the succeeding generations of the nation so that they would know that I am the Lord (10:2c). Whereas the word to Pharaoh was meant to reveal a God sovereign over all the earth, this word to the nation was meant to reveal that this Lord was God to them in a special sense; He was acting and had acted in their behalf. That word would be especially significant to the next generation reading the account as they stood on the cusp of protracted warfare in order to subdue and conquer the land God promised to them. In effect, while they had not been there in Egypt as the Lord performed these judgments, these judgments were just as much existentially "for them" and for their encouragement as they had been for the people who experienced them firsthand.

The whole of the narrative arrives at a denouement in 10:28–29. Pharaoh speaks better than he knows when in his frustration and humiliation he orders Moses, Get away from me! Beware, do not see my face again. In other words, "This is the last time we will meet." Moses acknowledges that he has spoken truly, but obviously not in the way he, Pharaoh, meant it. While it was Pharaoh who made the "death threat," it is Moses who will survive the final confrontation to come.

F. Free at Last (11:1–15:21)

The narrative carefully describes how it was that the children of Israel left Egypt and survived Pharaoh’s last attack: this section narrates Israel’s deliverance accomplished and Israel’s preservation from a pursuing enemy. Moses may have intended this section to encourage the people of Israel as they were getting ready to enter the land to possess it, a process that would require the displacement of a number of tribes who were living there. God would deliver Israel from her enemies during the conquest and preserve them from those who would pursue her to destroy her.

1. The Last Judgment or Plague (11:1–10)

11:1–8. The nature of last plague, the death of the firstborn, was revealed to Moses in simple but compelling terms. God probably revealed to Moses the information given in 11:1–3 during the three days of darkness, and Moses probably delivered it to Pharaoh at the same time as that in 10:29, immediately after Pharaoh’s death threat. God informed Moses that the protracted rounds of judgments were about to end. Moreover, not only would Pharaoh "let the people go" he would, in fact, drive you out (11:1). Furthermore, the Lord told Moses to instruct the people to ask for articles of silver and gold from the Egyptians. The nation could expect the Egyptian people to be generous to the Hebrews, for He would give the people favor in the sight of the Egyptians and Moses himself would be greatly esteemed in the land of Egypt. This was not only a remarkable reversal of fortunes, it also had a practical purpose—the nation would need that wealth to facilitate their journey and provide the wealth for the construction of the tabernacle (cf. 25:2–7; 35:20–29; 38:21–31). Also (11:3) this description of Moses as greatly esteemed by both Egyptians and the people of Israel would clarify why the Egyptians were willing to give up their wealth and to let the people of Israel go.

Moses delivered to Pharaoh a most chilling, and righteously indignant (11:8c), description of the coming judgment. In the dead of night (about midnight) death would visit the land of Egypt in an unprecedented way—all the firstborn in the land of Egypt shall die. The firstborn in a family was an especially significant position in Egypt as well as Israel, and in many other ancient patriarchal societies. The firstborn in any family was the main heir of the family fortune and the symbol of the ongoing social position of the family; much was invested in his well-being. The firstborn of the king or pharaoh was to inherit the throne, and with him rested, literally and symbolically, the fortunes and future of the dynasty and the nation. The death of the firstborn was a religious, social, and dynastic as well as personal/familial cataclysm. The extent of the catastrophe reached from Pharaoh’s throne to the most humble dwelling of slaves and even to the stables and barnyards of that nation. Literally every home, every house, every barn would know a death in Egypt that night (cf. 12:30b), and the devastation would produce a great cry (11:6), a singular national lamentation, of extraordinary and unequaled proportions. In one night it would have incapacitated this nation for a generation or more.

To make the injury even more poignant for the Egyptians, the sons of Israel would be spared even the insult of a barking dog, that is, no one would utter a word of protest against the nation. This was to show that God makes a distinction between His own and those who oppose Him. Pharaoh is even told that this catastrophe would cause his people to come to Moses, not to him, and demand that Moses Go out, you and all the people who follow you.

11:9–10. The summary verses (11:9–10) are intended to recall the entire previous narrative and add justification for the drastic calamity of the final judgment. The wonders that should have produced humility, repentance, and submission to the word of the Lord yielded a hard heart and culminated in a final, terrible retribution.

2. Deliverance from Death and Preservation by Passover (12:1–30)

a. The Preparation of the People for the Passover (12:1–13)

12:1–10. Preparation for the Passover consisted of several sets of instructions about pertinent topics. These instructions were probably also given during the days of darkness and were for all the congregation (‘eda) of Israel (12:3), and for the whole assembly (12:6). This is the first use of the term ‘eda—a term that appears over one-hundred times in the Exodus–Joshua narrative. It has the basic meaning of "community" or "congregation." Up to now the people have been identified as "Hebrews" or "sons of Israel," but from now on they are constituents of a unique assembly; they will be exclusively bound together by this Passover experience into the ‘eda. Furthermore, "whenever the text explicitly states that Moses addresses ‘the entire congregation of Israel,’ one can be sure that what will follow will be of extreme importance" (see Ex 35:1; Nm 1:2, 8; 26:2) (Hamilton, Exodus, 180). The Lord began with instructions regarding a new calendar (12:1–2). To emphasize the significance of the event at hand, the exodus itself, the Lord instructed Moses to reorient the Hebrew calendar so that the month of the exodus (this month), the month of Abib (cf. Ex 13:4; 23:15; 34:18; Dt 16:1; March/April), was the first month of the religious year. After the Babylonian captivity there was another re-orientation of the religious calendar; Abib was changed to Nisan (cf. Neh 2:1; Est 3:7) so, in effect, by the time of Christ, there were two calendars, one religious, one civil (secular) and the first month of the one was in the seventh month of the other.