JOB

Eugene J. Mayhew

INTRODUCTION

Author. The authorship of Job has been debated for centuries among both Jewish and Christian scholars. Traditional views within Judaism hold that the book of Job is of Mosaic origin, an ancient tradition that appears in the Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Baba Bathra 15 a-b. The problem with this view is that there is no such claim to authorship found in the book of Job. The book does not identify its author. Yet from the book’s manner and viewpoint, it would seem that the author was not Job.

From the earliest discussions and OT canonical lists, the book of Job has been included and its canonicity upheld. Over time, in printed Hebrew Bibles, Job was placed between Psalms and Proverbs in order of decreasing [scroll] length (Babylonian Talmud, Ber. 57b). A quotation of Jb 5:13 by the apostle Paul in 1Co 3:19 is "introduced by a formula that indicates that Job was canonical Scripture in the first century AD" (Robert L. Alden, Job, NAC [Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1993], 25). No evidence exists that the canonicity of the book of Job was questioned or disputed in Judaism or Christianity.

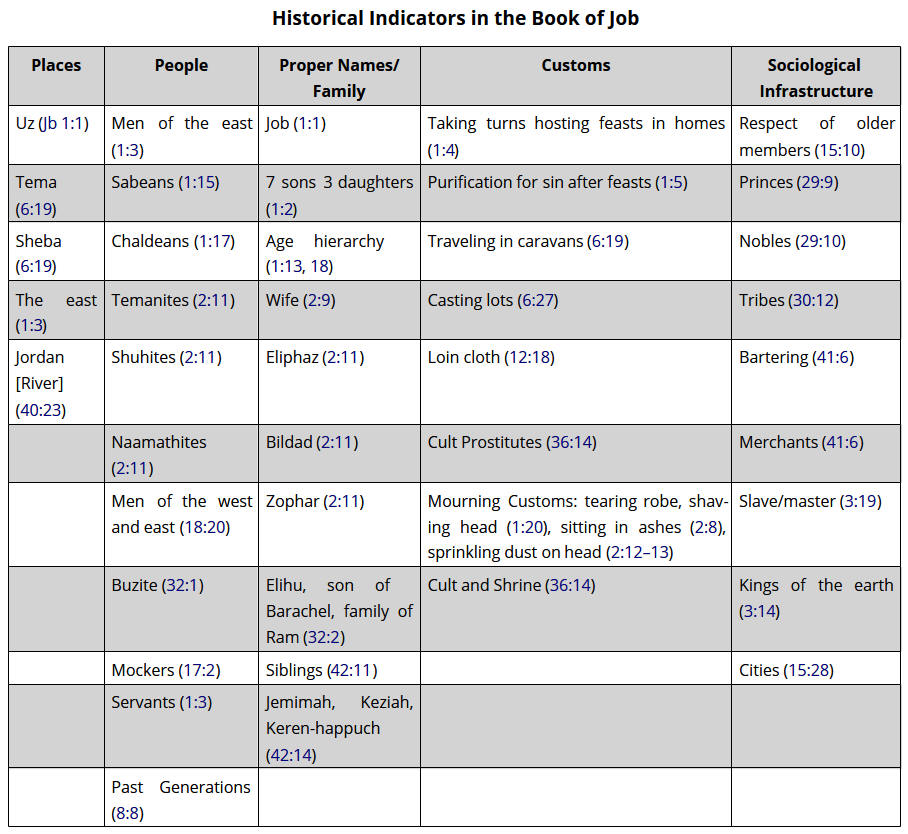

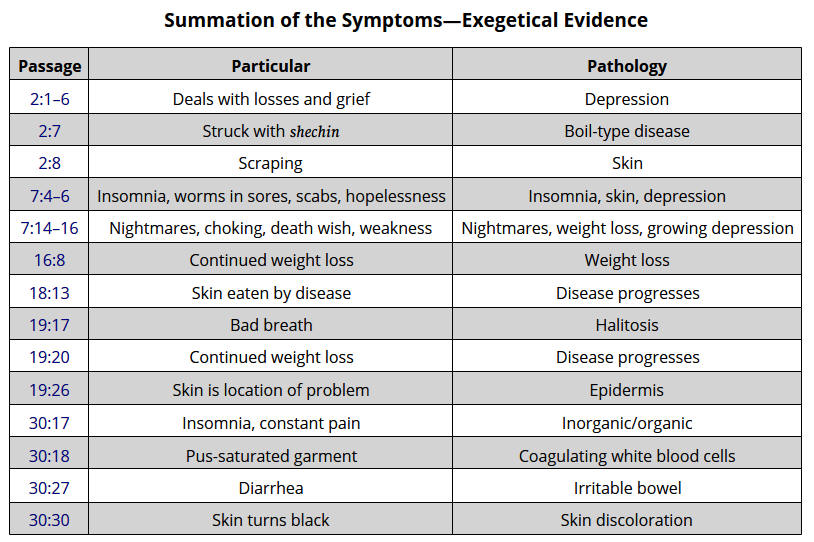

Date. The historical setting for the events of the book of Job was the development of the nations (Gn 10–11). This time period was postflood and post-Babel, as well as patriarchal (Gn 11:32–12:13). The prophet Ezekiel confirmed that Job was a real man and not a fictitious character (Ezk 14:14–20). A plethora of historical indicators within the book of Job (see chart) also confirms the historicity of the man and the events (Alden, Job, 31).

Based on this internal evidence and other biblical evidence, a pre-patriarchal or patriarchal date for the lifetime of Job is not unreasonable. However, one must distinguish between when Job lived and when the account was written. Just as Moses lived from approximately 1527 to 1407 BC and (by inspiration of God) was able to write accurately about Adam or Abraham who lived centuries or millennia before his time, so is the situation with the book of Job. Several items in the account show that both the text and events are very old. (1) Job’s lifespan places him solidly in the time of the early relatives of Abraham (Gn 22:20–24). (2) Neither the nation of Israel nor anything Israelite is mentioned in the book of Job because Job lived before or at the time of Abraham (Gn 11:32). (3) Many of the customs found in the book of Job are the same as those practiced by the patriarchs of ancient Israel. (4) New discoveries have shown that the Aramaic used in the book is ancient in date (Alden, Job, 26). It would appear from the evidence that Job lived in the land of Uz c. 2400–2100 BC. However, the book could have been written much later (as with the book of Genesis and Mosaic authorship).

The book of Job existed prior to these elements. (1) In AD 100 a copy of the Targum of Job, written in Aramaic, was shown to Rabbi Gamaliel. (2) At least four Job manuscripts were discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls of the Qumran community (177 BC–AD 100). (3) Jesus ben-Sirach (c. 132 BC), referred to Job in his writings in Ezk 14:14–20. (4) The Greek translation of the OT, the Septuagint (LXX), written c. 200 BC, included the book of Job. (5) Ezekiel referred to Job as a past example of righteousness (Ezk 14:14). (6) Jeremiah wrote about a specific nation ruled by kings in the land of Uz which was still well known in 600 BC, likely Syria (Jr 25:20).

Purpose. The aims of the author are quite clear as the book of Job sets forth a polemic against a wholesale approach to retribution—cause and effect for all sin in a person’s life. It also shows how a believer can triumph over tragedy even when much is unknown about the true God. The reader is given several visual snapshots into the unseen world of the throne of God and His workings (Alden, Job, 38–39).

Theme. The book of Job deals with a major problem area of fallen human existence, namely suffering. Why do people suffer (especially righteous people) if God is righteous and good? This book gives a larger perspective on the issue of theodicy (God’s justice in light of evil in the world) and demonstrates that sometimes suffering comes because of the supernatural conflict between God and Satan. In this ongoing conflict humanity often serves as the playing field for these supernatural matches of the strength, power, and stamina of the kingdom of God versus the kingdom of darkness. Ultimately, the book teaches God’s sovereignty over all.

God is in wise control (Jb 28) of the universe and of all issues in a believer’s life, both normal and abnormal, including triumphs and tragedies, affluence and poverty, adversity and prosperity. Even when those closest to the sufferer give wrong counsel and challenge the reasons for the misfortune, a righteous believer can stand confident that he is in God’s hands by understanding God’s work in creation. Therefore questioning or arguing with Him is unreasonable, but praising and repenting before Him is in order.

Chapters 1–2 and 42 are written in prose (narrative), and chaps. 3–41 are written in poetry, "except for brief introductions of the friends of Job just ahead of their addresses" (Alden, Job, 35). With the high density of poetry, Job has an impressive number of hapax legomena (terms used only one time in the book of Job or in the OT), and sometimes it is a challenge to grasp their meaning.

Critical scholars have tried to set forth the case that the book of Job was a mosaic that took shape over time as new portions of it were added. They view chaps. 1–2 and 42 as the original account, with all the poetic sections added later. But C. Hassell Bullock states, "The book of Job defies all efforts to establish its literary genre. While it has been viewed as an epic, a tragedy, and a parable, upon close analysis it is none of these even though it exhibits properties belonging to each of them" (C. Hassell Bullock, An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books [Chicago: Moody, 1979], 69).

Contribution. The book of Job draws back the curtain on a dynamic glimpse of the throne of God and interaction between God and Satan. God appears not only in control of Job’s suffering, but also omniscient and wise in the matter—wisdom belongs to God even in the most difficult aspects of life. As Job said, "With Him are wisdom and might" (Jb 12:13). The account demolishes the false ideas that the true God is aloof and unconcerned about human dilemmas. Rather, He is highly involved in a person’s life beyond our wildest imagination.

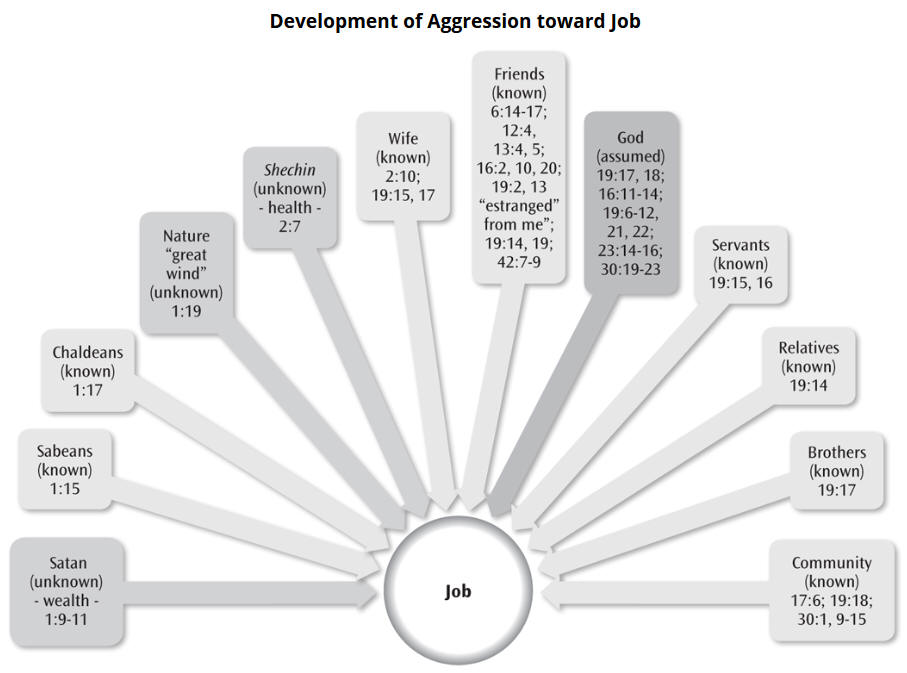

The facets of sin and suffering are greatly expanded in this early, inspired book. Many layers of suffering were unknown to the debaters as they tried in vain to sort out Job’s dilemma. Job 2 demonstrates the extent to which the adversary can assault the believer, even to the point of death (Rv 1:18–19; 20:11–14). And Job 2 shows the extent to which the believer is to trust God in the tragedies and uncertainties of life. This chapter informs the reader of the realm of supernatural conflict between God and the adversary. The awesome fact in the prologue of Job is that God set forth Job for the contest, and He is the One who initiated the challenge and contest. Yet God did this without removing His hand or His love from Job’s life. God appears as wisely sovereign and good in both the positive and negative aspects and events of individuals’ lives.

The account of Job shows us that God was active among humanity from the time of the flood until Abraham appeared on the stage of history, by the following facts: (1) The true God was well known to many people, and their knowledge of theology was extremely intricate and discussed among themselves. (2) Job appeared as a Gentile believer like Melchizedek and Jethro, who had knowledge of the true God apart from Abraham and Israel. (3) The interaction between God and Satan was clearly described, and the facets of suffering came into a clearer perspective. (4) Even a righteous believer could misunderstand God’s work and hurl false accusations against Him.

Where did the author of Job receive his either pre-Israelite or non-Israelite information? Very simply, there had to have been a body of truth orally transmitted from generation to generation from the time of Adam and Eve to the time of Moses.

The book of Job can be viewed as a beautiful and balanced seven-part chiasm. Beyond God’s sovereignty and His control over suffering is the assurance that suffering has meaning and purpose for the believer. Job 28, the psalm on wisdom, is at the heart of the book of Job (Elmer B. Smick, "Job," in EBC [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1988], 4:848).

Many scholars see the chiastic structure as the key to understanding the book’s strategy. It shows God’s wisdom (Jb 28) and the need for total dependence and trust in Him. See the chiastic structure of Job below:

The Book of Job Chiastic Structure Outline

A. Prologue: Righteous Job Sees His Life Go from Tremendous Triumphs to Phenomenal Tragedies (1:1–2:13)

B. The Lament of Job before His Friends concerning His Serious Sufferings (3:1–26)

C. The Rounds of Counseling with His Friends: Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar (4:1–27:23)

D. The Heart of the Message of the Book of Job: The Bastion of Wisdom Is Known Only by the True God (28:1–28)

C’. The Rounds of Counseling with His Younger Friend, Elihu (29:1–37:24)

B’. God’s Rhetorical Questioning of Job concerning His Intricate Care of Creation (38:1–42:6)

A’. Epilogue: Righteous Job Saw His Life Go from Phenomenal Tragedies to Tremendous Triumphs (42:7–17)

OUTLINE

I. Job’s Circumstances and Calamities (1:1–2:13)

A. Job’s Status before His Calamities (1:1–5)

B. Satan’s Challenge to God about Job (1:6–11)

C. God’s Permission to Satan to Afflict Job’s Possessions (1:12–22)

D. God’s Permission to Satan to Afflict Job’s Body (2:1–6)

E. Job’s Reaction to His Losses (2:7–10)

F. Job’s Three Friends Arrive to Comfort Him (2:11–13)

II. First Round of Speeches between Job and His Three Friends (3:1–14:22)

A. Job Laments His Condition (3:1–26)

B. Eliphaz Delivers His First Speech (4:1–5:27)

C. Job Responds to Eliphaz’s Charges (6:1–7:21)

D. Bildad Delivers His First Speech (8:1–22)

E. Job Responds to Bildad’s Charges (9:1–10:22)

F. Zophar Delivers His First Speech (11:1–20)

G. Job Responds to Zophar’s Charges (12:1–14:22)

III. Second Round of Speeches between Job and His Friends (15:1–21:34)

A. Eliphaz Delivers His Second Speech (15:1–35)

B. Job Responds to Eliphaz’s Charges (16:1–17:16)

C. Bildad Delivers His Second Speech (18:1–21)

D. Job Responds to Bildad’s Charges (19:1–29)

E. Zophar Delivers His Second Speech (20:1–29)

F. Job Responds to Zophar’s Charges (21:1–34)

IV. Third Round of Speeches between Job and His Three Friends (22:1–26:14)

A. Eliphaz Delivers His Third Speech (22:1–30)

B. Job Responds to Eliphaz’s Charges (23:1–24:25)

C. Bildad Delivers His Third Speech (25:1–6)

D. Job Responds to Bildad’s Charges (26:1–14)

V. Job Continues His Speeches (27:1–31:40)

A. Job’s Final Speech to His Friends (27:1–23)

B. Job’s Message concerning God’s Wisdom (28:1–28)

C. Job Reviews His Life (29:1–31:40)

VI. The Speeches of Elihu (32:1–37:24)

A. His First Speech about Job, His Friends, and God’s Work (32:1–33:33)

B. His Second Speech (34:1–37)

C. His Third Speech (35:1–16)

D. His Fourth Speech (36:1–37:24)

VII. God Speaks to Job (38:1–42:17)

A. God’s First Speech about His Knowledge (38:1–40:2)

B. Job’s Response to God’s First Speech (40:3–5)

C. God’s Second Speech about His Power (40:6–41:34)

D. Job’s Repentance before God (42:1–6)

E. Job’s Restoration by God (42:7–17)

COMMENTARY ON JOB

I. Job’s Circumstances and Calamities (1:1–2:13)

Chapters 1 and 2 are part of the prose section of Job, setting forth the issues and characters in quick succession. Job’s sterling spiritual character, his family and possessions, Satan’s accusations and attacks on Job, Job’s reactions, and the arrival of his friends—all are set before the reader in rapid fashion, like an edited film speeding through the preliminaries. Everything happens quickly, yet the dialogue that follows unfolds at a very studied pace. The pace slows, and the plot is simple. The prologue is necessary background told in rapid narrative style to get the reader quickly to Job’s agonizing confrontations with his friends and with God.

A. Job’s Status before His Calamities (1:1–5)

1:1. Job lived in the land of Uz. The location of Uz is disputed, as there are three people with that name in the book of Genesis (10:23; 22:21; 36:28). However, the only one who could have lived, become famous, and had a land named after him by the time Job existed would have been Uz son of Aram (Gn 10:23). Aram had settled the area now known as Syria, and it appears from the evidence that his son Uz had a large portion of ancient Syria named after him.

As noted in the introduction, writing after Syria had been conquered by the Assyrians, Jeremiah referred to Syria as "the land of Uz" (Jr 25:20). Therefore at the time of Jeremiah, Uz was an ancient name that referred to the area formally known as Syria before it fell to the Assyrians. There is a second biblical reference to Uz as a possession or neighbor of Edom (Lm 4:21).

Other theories on the location of Uz are northwest Arabia and Edom. However, Jeremiah referred to it as a nation with many kings (Jr 25:20). Thus Uz was not an alternative name for Edom, or for Philistia, Moab, or Ammon because they are listed apart from the land of Uz (v. 21). Gleason L. Archer notes: "in Berlin Execration Texts … Job (‘Iyyob) appears as the name of a Syrian prince living near Damascus" (Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1982], 236). There is not enough evidence to establish that this refers to the biblical Job, but from this discovery the exact personal name is used in the region of ancient Aram (Syria) where Aram had a son named Uz (Gn 10:23). Unger adds, "The most likely location of Uz is Syria (Aram), rather than Edom, Idumea, or another area. The Uz of Gn 10:23 is apparently the only biblical person who could have established an area bearing his name by the time Job lived, apparently in the Abrahamic or pre-Abrahamic age" (Unger’s Commentary on the Old Testament [Chicago: Moody, 1981], 1:679).

The time frame of Job was patriarchal (see discussion in introduction). The book yields at least seven facts about Job’s age:

1. Job had ten grown children with sons who owned their own houses.

2. He had the reputation as being the greatest man of the east before his suffering took place (1:2–4).

3. He sat with the elders at the gate of his city (29:1–12).

4. Job was an elder, and younger Elihu was hesitant to speak up about his suffering.

5. He had ten additional children after his suffering (42:13).

6. His name ‘iyyob was a common name during the time of the patriarchs and even before as it appears in texts discovered at Ugarit, Mari, and among the Amarna Letters and the Egyptian Execration Texts.

7. Job lived 140 years beyond his sufferings and saw his next generations born (42:16–17).

A conservative estimate of the lifespan of Job based on this internal evidence would be that he lived to be much older than Abraham, since Jb 42:16–17 informs the reader that Job’s lifespan was 140 years, after his sufferings, almost equal the length of Abraham’s total life of 175 years (Gn 25:7). This would place Job as living after the Noahic flood and before the time of the patriarch Abraham.

Roy B. Zuck (Job [Chicago: Moody, 1978], 10) adds these reasons for Job having lived in the time of the patriarchs:

1. Job’s wealth was reckoned in livestock (1:3; 42:12), which was also true of Abraham (Gn 12:16; 13:2) and Jacob (Gn 30:43; 32:5).

2. The Sabeans and Chaldeans (Jb 1:15, 17) were nomads in Abraham’s time, but not in later years.

3. The Hebrew word qesitah, translated "piece of money" (42:11), is used elsewhere only twice (Gn 33:19; Jos 24:32), both times in reference to Jacob.

4. Job’s daughters were heirs of his estate along with their brothers (Jb 42:15). This, however, was not possible later under the Mosaic law if a daughter’s brother(s) were still living (Nm 27:8).

5. The name Shaddai is used of God 31 times in Job (compared with only 17 times elsewhere in the OT) and was a name familiar to the patriarchs (Gn 17:1; also cf. Ex 6:3). Edersheim wrote this about the years before Abraham: "It will be readily understood that the number of those ‘born out of season,’ as it were, from among the Gentiles, must have been larger the higher we ascend the stream of time. The fullest example of this is set before us in the book of Job, which also gives a most interesting picture of those early times" (Alfred Edersheim, The Bible History [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1969], 1:5–6).

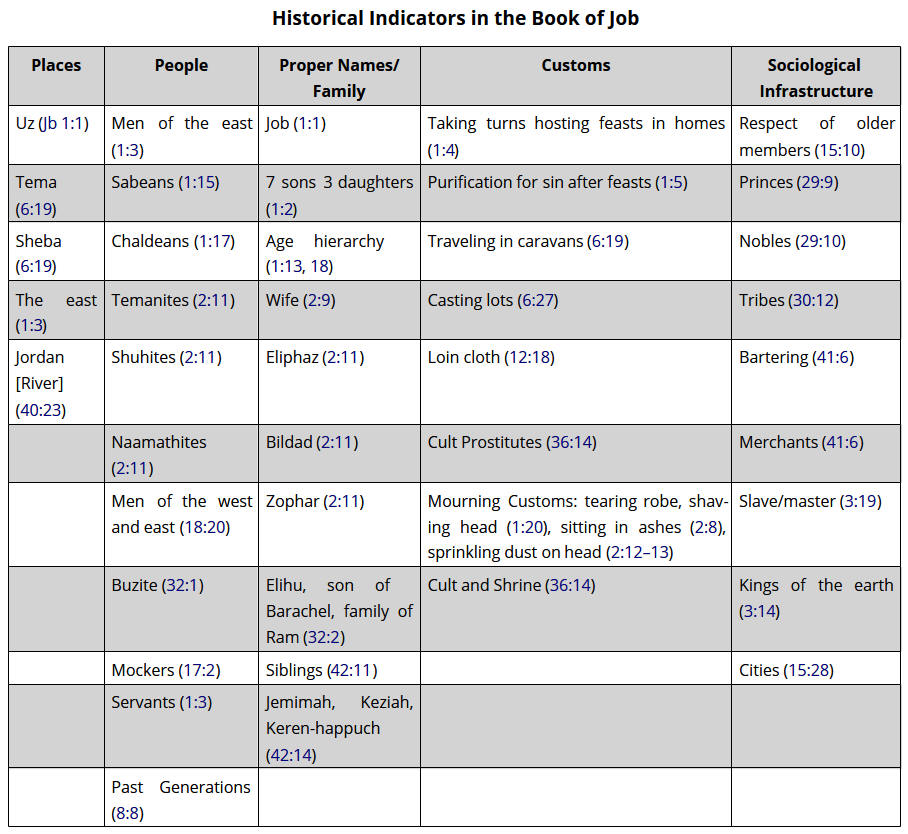

1:2–3. The true God blessed Job’s life and work. In addition to his 10 children, Job also had many possessions, including 7,000 sheep, 3,000 camels, 500 yoke of oxen, 500 female donkeys, and many servants. He was both wealthy and godly—two characteristics not often found together. He was a remarkable man indeed.

Perhaps Job was like many patriarchs who were ancient teamsters, moving goods in the lucrative caravan business, as large caravans used hundreds of animals. The camels, oxen, and donkeys were the standard beasts of burden in the ancient Near East at that time. One would become well known over a vast region by being in that business. His wealth, like that of Abraham and others, was stated in animals owned (Gn 13:2, 6; 24:28–35; cf. 1Sm 25:2; 2Kg 3:4).

It is written that Job was the greatest of all the men of the east (v. 3). According to other biblical authors the east (qedem) refers to a definite area or region during the time of the OT. In later times the east had ominous overtones for the people of Israel because it was from the east that God summoned the great Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar, to come and destroy Jerusalem and carry the people away into captivity. But this would be many centuries after the time of Job.

Other references to "the east" include (1) Gn 10:30, referring to where Shem, Noah’s son, settled after the flood; (2) Jdg 6:3, 33; 7:12–8:10, referring to the area of the Midianites; (3) Jr 49:28, referring to a region near Kedar; and (4) Ezk 25:2, 4, referring to an area of the Ammonites. Therefore the east encompassed the district from Damascus to Arabia and over to what later became Assyria. Job’s great stature in that ancient society resulted not only because of his accumulation of goods and animals, but also because he obeyed the true God and was a man of integrity (Jb 1:1).

1:4–5. The strong evidence that Job lived during or even before the classic patriarchal period of the OT appears in his spiritual activities on behalf of his children. He served as Abraham did as the family priest (1:4–5; 42:8) (Alden, Job, 26, 31, 52). Unger notes, "He offered burnt offerings, as symbolic of the messianic expiation of sin, to make atonement for sins his children might have committed" (Unger’s Commentary on the Old Testament, 1:680, cf. Deuteronomy Rabba, II). Regarding making offerings, the text states, thus Job did continually. This shows, as Albright concludes, "that Job may have been a contemporary of the patriarchs in the pre-Mosaic age" (William Albright, "The Old Testament and Archaeology," in Old Testament: A General Introduction to Commentary of the Books of the Old Testament, ed. Herbert C. Alleman and Elmer E. Flack [Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1948], 155; see also William F. Albright, Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan, [London: Athlone Press, 1968], 67–71).

Archer concludes, "There are no tenable grounds for the theory of a fictional Job. The Apostle James was therefore quite justified in appealing to the example of the patriarch Job (James 5:11), in his exhortation to Christian believers to remain patient under tribulation. It is needless to point out that the Lord could hardly have been merciful and compassionate to a fictional character who never existed" (Archer, Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties, 236–37).

B. Satan’s Challenge to God about Job (1:6–11)

1:6–8. Satan came into the court of heaven as one of the sons of God permitted to stand before God. From other Scriptures we know that angels, both unfallen and fallen (Satan in Jb 2), were allowed to appear before Yahweh in heaven. In Zch 6:5, the prophet is told that his vision of the four chariots represents "the four spirits of heaven, going forth after standing before the Lord of all the earth." While this reference does not identify angels by name, this is a legitimate interpretation. There is no question, however, about Lk 1:19, when Gabriel declared to Zacharias, "I am Gabriel, who stands in the presence of God."

The expression "sons of God" is used of both godly people and godly angels who follow the true God. Here the expression is used of angels, based on Jb 38:7. In this particular heavenly audience Satan was also allowed to attend (Eph 2:2; 2Pt 2:4; Jd 9; Rv 12:7–9). The root verb for the Hebrew word satan has the potential meanings of "to oppose, to come in the way," "to treat with enmity." In the book of Job, this opposer or adversary always occurs with the definite article, hence, hassatan—"the opposer" or "the adversary." In Rv 12:7–9; 20:2, it is another name for the fallen cherub that relates back to Gn 3; it is not a late postexilic concept or doctrine. Other occurrences of the title in the OT are in 1Ch 21:1 and Zch 3:1–2. Delitzsch notes, "But, the conception of Satan is indeed much older in its existence than the time of Solomon; the serpent of paradise must surely have appeared to the inquiring mind of Israel as the disguise of an evil spirit" (Franz Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Book of Job, 3 vols., trans. F. Bolton [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1949], 1:28). When God asked Satan where he had been, Satan replied that he had been roaming about on the earth (Jb 1:7). Satan may have been doing this while "prowl[ing] around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour" (1Pt 5:8), which is his constant goal.

It is clear that God was the One who introduced Job into the scene of His audience with Satan (v. 8). The Lord referred to Job as My servant, which Zuck calls an "honorable title" (Job, 15). God praised Job’s devotion, and was confident that Satan would also discover that Job’s piety was far more than a superficial devotion.

1:9–11. Satan could not deny Job’s devotion to God, but he asked the question, Does Job fear God for nothing? This is an issue human beings have wrestled with for generations. From Job’s day to the message of the so-called health and wealth preachers of today, there has been no lack of people to suggest that those who serve God can expect to reap material benefits in this life as well as eternal life in heaven.

After Jesus’ disciples watched a rich man come and ask Jesus about inheriting eternal life, and then go away sadly (Mk 10:17–22), they wondered what they would receive for giving up all to follow Jesus. The Savior responded, "Truly I say to you, there is no one who has left house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or farms, for My sake and for the gospel’s sake, but that he will receive a hundred times as much now in the present age, houses and brothers and sisters and mothers and children and farms, along with persecutions" (vv. 29–30). Jesus’ promise of persecutions for His faithful followers does not fit with the theology of the "name it and claim it" teachers who say that material prosperity is guaranteed by God.

Satan knew he could not impugn Job’s demonstrated piety, so he impugned Job’s motives instead. The adversary complained to God about three aspects of Job’s faithfulness. (1) God had made a hedge of protection around Job and all he possessed. (2) Job worshiped God because of what he was receiving from Him. (3) If God allowed Job’s blessings to be taken from him, he would curse You to Your face (v. 11).

From ancient times Satan has been the grand accuser of the servants of God (Rv 12:10). However, God, not Satan, made the initial challenge and set the boundaries for the testing of Job of Uz. Many Bible teachers miss this foundational truth and end up with false conclusions about Job’s ordeal. It was God who challenged Satan concerning Job.

In the first assault that was negotiated and authorized in heaven, God allowed Satan to test Job, but limited Satan’s testing to Job’s possessions and family. Delitzsch states, "There is in nature an entanglement of contrary forces which Satan knows how to unloose, because it is the sphere of his special dominion; for the whole course of nature, in the change of its phenomena, is subject not only to abstract laws, but, also to concrete supernatural powers, both good and bad" (Biblical Commentary on the Book of Job, 1:28).

Several key questions are raised by these early verses of Job. Zuck summarizes them well: "Will Job be seen as one who will serve God even if he gets nothing in return? Will anyone serve God for no personal gain? Is worship a coin that buys us a heavenly reward? Does man serve God to get blessings, fearing that failure to worship will bring punishment? Is piety part of a contract by which to gain wealth and ward off trouble?" (Job, 15, italics original).

C. God’s Permission to Satan to Afflict Job’s Possessions (1:12–22)

1:12–19. In rapid succession Job saw many of his earthly possessions taken from him—and finally all 10 of his children were killed in one moment. The Sabeans may have come from the region of Sheba, in southwest Arabia, or from a town named Sheba, near Dedan, in Upper Arabia (Gn 10:7; 25:3). The Chaldeans were fierce marauding inhabitants of Mesopotamia.

Four servants came to Job to report the losses he had incurred. Delitzsch summarizes, "Satan has summoned the elements (nature) and men for the destruction of Job’s possessions by repeated strokes. That men and nations can be excited by Satan to hostile enterprises is nothing surprising (cf. Apoc. 20:8); but here, even the fire of God and the hurricanes are attributed to him" (Biblical Commentary on the Book of Job, 1:63).

1:20–22. A solid faith perspective is extremely important when suffering comes into a believer’s life. Job worshiped God when these tragedies struck him and his wife. He acknowledged that the true God can give or take and that a believer should not blame God for any misfortune. William Dyrness adds, "Job deals with the ancient problem of the innocent sufferer. It faces squarely the reality of evil and human suffering but shows the futility of calling God to account (Jb 40:6–14) … the attitude of sufferers is more important than the answer to their questions" (Themes in Old Testament Theology [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1979], 192–93). Job expressed both his grief and his submission to God when he tore his robe and shaved his head and fell to the ground and worshiped (v. 20).

The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away (v. 21) was Job’s declaration of trust. This statement indicates that Job saw God as the ultimate cause of his misfortunes, though not the immediate, direct cause, which came from the other participants. This is an important consideration for the entire book—God is presented as the One who ordained and sovereignly stood behind Job’s situation.

Equally important is the statement in v. 22: Job … did not blame God. The Hebrew word translated blame connotes "unsavoriness, foolishness." It is probably used metaphorically here with the sense of "moral repugnance" or "reprehensibility." In addition, it sometimes carries the sense of "repulsiveness," i.e., a state or condition which causes feelings of abhorrence and loathing (Jr 23:13).

While Job ascribed to God the ultimate causation of his losses (The Lord has taken away), he did not hang upon God the moral culpability (the guilt) of them. God is rightly seen in Scripture as the ultimate, not direct, cause of the sin, evil, and suffering in the world (that is, He is sovereign over them, ordains them, and brings them about indirectly through the free actions of people or demons as part of His providence; see Gn 50:20; Ac 2:22–23; 4:27–28). But God is never blamed for the moral guilt of evil—even by Job—and is never the One who tempts people to sin (Jms 1:13). Moral guilt is always ascribed to people and demonic beings. This is part of the mystery of God’s sovereignty, and its interaction with the moral responsibility of moral agents, whether human or demonic.

In the first assault by the adversary, Job felt the tremendous loss of his children, herds and flocks, and many servants (1:16–22). In chap. 2 the angelic adversary requested authorization and received permission to launch a second assault against Job since his first assault did not cause him to curse God (Jb 1:11, 22; 2:5). As Zuck points out, "Job was subjected to two tests—one on his possessions and offspring (1:6–22) and one on his health and his reputation (2:1–10). In each test were two scenes, one in heaven and one on earth. Each scene in heaven included an accusation by Satan against Job, and each scene on earth included an assault by Satan against Job" (Job, 15).

Satan failed in his first attempt to discredit Job’s faith and expose him as a person who worshiped God only for the protection and possessions He provided. Job’s response proved Satan to be completely wrong in his confident prediction that Job would curse God if calamity befell him. Job’s humble submission and his worship of God at a moment of supreme grief and despair verified God’s words that Job was, indeed, unlike any other person on earth. However, Satan was not ready to quit the attack.

D. God’s Permission to Satan to Afflict Job’s Body (2:1–6)

Once again, Satan called God’s word into question and impugned Job’s motive for worshiping Him—even though Job had nothing left at this point but his life. This was enough for Satan to accuse Job a second time of serving God only for personal benefit.

The text of Job provides no time frame between Jb 1 and 2; therefore, the elapsed time between the first assault in chap. 1 and the second major assault in chap. 2 is uncertain. However, it would seem that the two assaults were somewhat close together (v. 11), as reflected in: (1) the statement of Job to his wife about accepting adversity (v. 10); (2) the reference that seems to include the bad events recorded in 1:6–22 and 2:7; and (3) the reference in 2:11 to "all this adversity." However, as Robert Gordis notes, "For the news to reach the friends in their several countries and for them to arrange for a meeting suggests that Job’s suffering had extended over a considerable period of time" (The Book of God and Man: A Study of Job [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965], 22). The context necessitates a period of time consisting of at least several months to over a year. As chap. 2 opens, Job is in the midst of dealing with his heavy losses and grief when the physical affliction (the second assault) comes on him (vv. 7–8).

2:1–6. The context of chap. 2 is in the aftermath of Job’s horrible losses described in chap. 1. Meanwhile, back in heaven Satan appeared a second time, and God again set forth a challenge to him. To set the stage for this challenge, Satan snarled, Skin for skin! (v. 4). If Job’s body can be touched with adversity, he will curse You to Your face (v. 5). To this, God issued another limitation: the adversary could touch Job’s body, but not kill him: only spare his life (v. 6).

E. Job’s Reaction to His Losses (2:7–10)

2:7–10. Then the adversary went from heaven to earth and inflicted Job with a boil-type disease. Job initially tried to alleviate the pain and mourn, in ancient Near Eastern style, for the calamities he had encountered. The author noted, And he took a potsherd [a broken piece of pottery] to scrape himself while he was sitting among the ashes (v. 8). Even Job’s wife became part of the problem by telling him to give up, to curse God and die (v. 9). Responding to his wife, Job stated that believers in their misfortunes can expect both good and adversity from God (v. 10). This fits with the strong statement of the psalmist who wrote, "Let the sound of his praise be heard; he has preserved our lives and kept our feet from slipping. For you, God, tested us; you refined us like silver. You brought us into prison and laid burdens on our backs. You let people ride over our heads; we went through fire and water, but you brought us to a place of abundance" (Ps 66:8b–12 NIV).

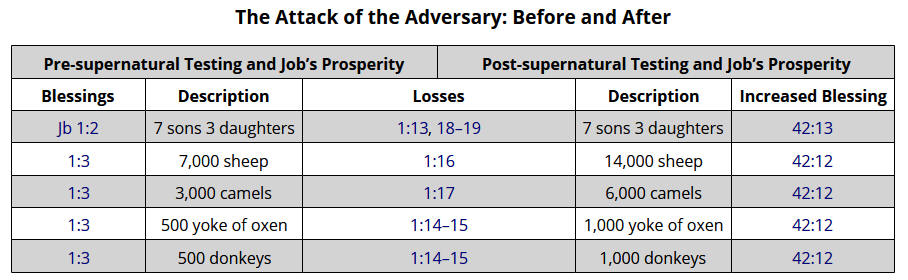

A Jewish legend states that "Job was stricken by Satan with fifty plagues" (Targum Yerushalmi; Exodus R., 23:10), and another that says his suffering endured for a year (Testament of Job, v. 9; Isadore Singer, "Job," in The Jewish Encyclopedia [1904], 7:194). Others make Job the all-time sufferer of humanity. However, from Job’s symptoms, one of several known diseases could have been the culprit Satan used to cause terrible pain and suffering. The chart on the following page lists the symptoms that the text of Job indicated he had.

The angelic adversary actively struck Job with a physical disease identified as shechin (v. 7). This term means a boil or eruption (Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles A Briggs, Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1906], 1006, hereafter BDB), and occurs in other Semitic languages, such as Akkadian, Assyrian, Ugaritic, and Aramaic, denoting "heat, fever, inflammation and the like." It stems from the verb "to be inflamed." The writer states that Satan smote Job with sore boils from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head (v. 7). The Hebrew word for "sore" is ra’ meaning "bad, noxious, hideous" (Dt 28:7; 2Ch 21:6; Ec 6:1). The Septuagint translator chose the term elkos, which is used in the NT of an ulcer (Lk 16:20; Rv 16:2). In the OT the term is applied to skin diseases (Marvin H. Pope, Job [Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973], 2). The differences of opinion among various biblical scholars and medical doctors concerning the range and precise designations of shechin arise from its use in relation to different skin diseases in the OT and in other ancient Near Eastern literature.

Numerous theories have been advanced concerning Job’s disease: leprosy, elephantiasis, acute dermatitis, oriental sore, Egyptian boil, smallpox, pemphigus foliaceus, ecthyma, erythema, multiple disease, psychosomatic, unique adversary theory, and no disease theory. Zuck for one favors pemphigus foliaceus, an auto-immune blistering disease of the skin and mucous membranes with characteristic lesions that are scaly, and crusted erosions (Job, 19). The "Egyptian boil" is taken from a reference to "the boils of Egypt" in Dt 28:27. Later, the same words as in Jb 2:7 are used in Dt 28:35 to describe the suffering that would come to Israel because of disobedience: "The Lord will strike you on the knees and legs with sore boils, from which you cannot be healed, from the sole of your foot to the crown of your head."

It is best to understand that shechin is a general word that describes a number of boil-type skin diseases (the context of the book indicates that it was a serious skin disease). In Jb 18:13 Bildad said of Job, "His skin is devoured by disease. The firstborn of death devours his limbs." No one can state the exact nature of the disease. A number of diseases can cause boils all over the body and reveal the symptoms listed in the book.

The phrase from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head has been taken to mean that the boils occurred all over Job’s body. This merism—similar to "And in His law he meditates day and night" (Ps 1:2) and "from Dan even to Beersheba" (2Sm 3:10)—is employed to describe the extent of the boil outbreak on the skin of Job without listing every body part where a boil erupted. The boils were multiple and every region of Job’s skin was affected by them. Thus the adversary inflicted Job with a horrible physical disease in this second assault.

Realizing that he had contracted a serious boil-type disease, Job responded by scraping himself with a potsherd as he sat in the ashes. Job’s reaction reveals the seriousness of the disease and of his emotional state. Job’s skin problem produced itching to the point of morbid aggravation. This word scrape or "scratch" occurs in Aramaic and Phoenician to refer to "flesh-scrapers." In this gruesome scene Job selected a ragged-edged potsherd with which to scrape himself to alleviate the pain and itching. Broken pieces of pottery were used for makeshift tools such as scrapers and scratchers.

To v. 8 LXX translators added the last three words "without the city." Since lepers were required to live outside a camp or town, these three words have added support to the view that Job’s disease was leprosy. Acknowledging such an interpretation, Gordis adds, "Job sits on the ash-heap outside the city, not as a sign of mourning, but rather because of the contagious character of his disease and his loathsome appearance" (The Book of Job [New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America of 1978], 21). However, Edward J. Kissane is right to argue against the LXX addition: "The Greek text adds ‘without the city’ and this has given rise to the common view that Job retired outside the city. But the text itself does not say this, and the presence of his wife would indicate rather that he was still at his own house" (The Book of Job [Dublin: Browne and Nolan, 1939], 10). Job’s sitting "among" the ashes was a custom in the ancient Near East that indicated mourning. In a time of mourning, an easterner could simply take ashes from a campfire or fireplace and put them in a convenient location and begin the mourning process. Therefore Job could have been mourning at his home.

If Job had been on the dunghill or the city dump, then the following would seem to be true: (1) Job’s friends spent an entire week either on the dunghill or in or near the dump; (2) the entire conversation between Job and his friends took place there as well, since 2:12 shows them joining him in this custom; and (3) ashes presuppose the dunghill. But a more plausible interpretation is that Job went outside his home and participated in a well-established custom that pictured the inner turmoil of the mourner or sufferer. When his friends came close to his home, they joined him in his mourning near his dwelling. Then Job’s suffering was intensified from yet another angle.

In addition to the anguish of suffering with an acute boil-type disease, the adversary also used Job’s wife in the assault, and in the near future would also use his relatives and friends. She asked, Do you still hold fast your integrity? Then she uttered her famous command that aligns with the contest in heaven between the adversary and God. She should have been Job’s greatest strength apart from God, but she told him to curse God and die! The Hebrew text uses the word barakh, bless, as a euphemism for "curse" since the idea of cursing God was unthinkable.

Concerning the use and understanding of the words curse God, E. Dhorme comments:

The sharp reply which Job’s wife gets in v. 10 excludes the translation of curse as "bless Elohim" (Targ. and Vulg.). As has been understood by Syriac and some Greek interpreters, the word ["curse"] is a theological euphemism which we have found in the whole of the narrative (v. 5 and 1:5, 11). Hence we shall continue to read curse as before: "Curse Elohim and die!" It is not necessary to see death as a consequence of the suggested cursing. It is simply a matter of succession in time (Commentary on the Book of Job [Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1967], 20).

Smick writes that the word "die"

is a universally used Semitic root for dying and death … the literal demise of the body in death is usually in view.… The Canaanites employed it as the name of the god of death and the netherworld, Mot (cf. ANET, 138–142).… In Ugaritic, the god Mot was a well-defined figure who ruled the netherworld, a land of slime and filth. ("Job")

In addition to this command by Job’s wife, the LXX places a lengthy speech in her mouth. About the origin of her speech H. H. Rowley states: "Ball suggests that it may go back to a Hebrew original, but there is no reason to suppose it belonged to the authentic text" (Job, The Century Bible [New York: Thomas Nelson, 1970], 39).

Some commentators have understood the advice of Job’s wife as compassionate rather than contemptible, a wish for a quick death instead of prolonged suffering. But this idea does not do justice to the context, since her statement would require Job to abandon his integrity and his trust in God—the very outcome Satan also tried to bring about. It is preferable to view Job’s wife as expressing bitterness toward God.

Job responded that his wife spoke as one of the foolish women, as a person with no spiritual discernment. Delitzsch states: "The answer of Job is strong but not harsh, for the [spiritual insensitivity] is somewhat soothing. The translation ‘as one of the foolish women’ does not correspond to the Hebrew; [nabal] is one who thinks madly and acts impiously" (Biblical Commentary on the Book of Job, 1:72). The word nebalaah, meaning "foolish or senseless," is used of a person who lacks moral and spiritual perception.

Job then said to his wife, Shall we indeed accept good from God and not accept adversity? Besides accepting "good" benefits from God, Job also realized that believers must accept adversity. The term ra’ means "distress, evil, wrong, injury, calamity," and this verse once again indicates God’s providence over evil and suffering in the world (see the comments on 1:21–22). Job’s stance points up the need for perseverance in the midst of trials and problems. As the second assault progressed in intensity, Job continued to trust in his relationship with his God. But the calamities, the first and second assaults that Job had experienced, stretched him to the breaking point.

Nevertheless, in all this Job did not sin with his lips. The word "sin" is chata’, which means "miss, go wrong, sin, commit a mistake, miss the mark" (BDB, 306).

In Akkadian the verb hatu means "to sin, to neglect," and in Ugaritic the verb refers to "sin" three times (Cyrus H. Gordon, Ugaritic Textbook [Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1967], no. 19/952). Regarding the phrase with his lips, Gordis states, concerning Job, "Purity of speech reflects the integrity of one’s spirit" (The Book of Job, 22).

F. Job’s Three Friends Arrive to Comfort Him (2:11–13)

2:11–13. This section concerning the entrance of his friends closes one episode and begins a new one with Job’s friends entering the scene. The men who came to visit are referred to as friends, that is, companions. Job’s friends Eliphaz, Bildad, Zophar, and Elihu demonstrated that they believed that problems and turmoil were always a result of serious kinds of sin. However, the account shows that this approach to suffering is both theologically shallow and often wrong.

Gordis states, "For the news to reach the Friends in their several countries and for them to arrange for a meeting suggest that Job’s suffering has extended over a considerable period of time" (The Book of Job, 22). They made an appointment together, that is, the three friends worked as a team in planning to come as a group to help Job. The reason for their visit was to sympathize with and comfort Job. Obviously they came with good motives. When they saw Job’s condition, they were moved to identify with his situation, and they entered the well-established custom of mourning.

Seeing his horrible condition, his friends raised their voices (v. 12). At the same time they wept, and tore their garments. Leonard Coppes comments that this "has to do with rending cloth or a similar substance.… Most frequently, it refers to an act of heartfelt and grievous affliction (tearing one’s upper and under garment, "qara’," in Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, ed. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer, Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke [Chicago: Moody, 1980]: 2:816).

When they saw his condition, they were overwhelmed and joined him in a week of silent mourning before they began to speak (v. 13). They were moved to tears because of the condition of their friend Job.

No doubt the week of silent mourning allowed time for the friends to contemplate possible causes of Job’s catastrophes as they witnessed his physical agony and inner despair. Previously in 1:20–21, Job had responded by participating in some outward expressions of mourning by tearing his robe, shaving his head and sitting on the ground. But unlike these three friends, Job did not throw dust or ashes on his head. Instead he worshiped God and did not blame Him.

II. First Round of Speeches between Job and His Three Friends (3:1–14:22)

A. Job Laments His Condition (3:1–26)

3:1–4. Totally distraught with his condition, Job started to lash out at his existence. Cracks started to develop at this point in his physical, emotional, and spiritual stamina. He began as a sterling example of dealing with personal disasters, but as the intensity of the tests increased, Job began to doubt, and he started to target God. In lament fashion he bemoaned (1) his conception and the night he was conceived in the womb (vv. 2–10); (2) his birthday and wondered why he did not die the moment he was born (vv. 11–15); and (3) that he was not miscarried at some point during his mother’s pregnancy (vv. 16–19).

Job began his lament by curs[ing] the day of his birth, literally "the day" (v. 1). He did not curse God, as Satan had hoped and his wife had advised him to do. His wish was that the day on which he was born could have been blotted off the calendar. He even went back farther in time to bemoan the night of his conception, personifying the night as announcing the gender of the child who was conceived (v. 3). By wishing that God above would not … care for it (v. 4), Job was saying that perhaps if God did not take notice of the day of Job’s birth, perhaps He would not take notice of Job now in his suffering.

3:5–10. These verses draw heavily on the image of darkness, to which Job referred five times. The word "blackness" is a hapax legomenon meaning the darkness that results from an event in nature that darkens the sky, such an eclipse or a tornado. In v. 7, Job continued his strong lament by wishing that his mother had gone barren on the night he was conceived. The Leviathan (v. 8) was a seven-headed sea monster in ancient Near Eastern mythology (although some commentators believe it referred to a crocodile of the Nile River). The mythological understanding fits the context better, since the Leviathan was believed to swallow the sun or moon, thus causing the darkness that would occur in an eclipse, for example. Job was not expressing his belief in mythology, but simply using a common idea of his day to illustrate his desire for the day of his birth to be swallowed up and disappear. Because the womb of Job’s mother did open at his conception, he was forced to see trouble rather than having it hidden from his eyes (v. 10).

3:11–19. Job continued to pour out his complaint, wondering why he was not stillborn. Short of this, he also lamented that he had been welcomed as a newborn. The question, why did the knees receive me? (v. 12) could refer to his mother taking him in her lap, or the patriarchal custom of placing a newborn on his father’s knees as a symbol of the child’s acceptance (cf. Gn 48:12; Zuck, Job, 25). Job continued by saying that he could have achieved the same goal of death if only his mother had not nursed him (v. 12). Job was so distraught that he felt it would have been even better had he been a miscarriage at some point during his mother’s pregnancy (vv. 16–19). Either way, Job could have enjoyed rest in the grave.

3:20–26. Job’s lament differed significantly from the wise counsel for which he was known in the east. As he questioned, Why is light given to him who suffers, and life to the bitter of soul? (v. 20) he obviously longed to die. This was the third "Why?" question in Job’s lament (the first two were in vv. 11–12). Job’s remorse was, For what I fear comes upon me (v. 25). The translation "For the thing which I greatly feared" (KJV) looks backward, possibly to the beginning of Job’s trials, as the news of one loss spurred his fear of the next one. The NASB translation used points to Job’s present suffering, which seems to better fit the context.

B. Eliphaz Delivers His First Speech (4:1–5:27)

4:1–2. Eliphaz is identified as a Temanite (4:1). Teman was an important city in Edom, known as a center of wisdom studies (Jr 49:7; cf. Jb 6:18–20; Is 21:14; Jr 25:23; and Ob 8–10). He addressed Job’s turmoil and immediately confronted Job’s conclusions. He attempted to clear the air and to counter Job’s thinking. In fact, he said, But who can refrain from speaking? (Jb 4:2b). After a week of silently observing, Eliphaz said he could not refrain from speaking even if he so desired. He had come to some conclusions of his own to present to Job. Bullock says, "[Eliphaz’s] basic contribution to the dialogue was probably the universal principle that he propounded: the universe operates according to the law of cause-effect (4:7–11).… A second principle put forth by Eliphaz was that suffering may be viewed as the chastisement of God with the purpose of correction and healing (5:17–18)" (An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books, 90–91).

4:3–11. Eliphaz was most likely the oldest of Job’s three visitors, since he spoke first; protocol of the day would demand it, in fact. He reminded Job of the wisdom and excellent counsel for which Job was known, while helping so many people in the past (vv. 3–4). However, now that tremendous misery had come on him, Job failed to take the counsel he had given to others. He was impatient and dismayed (v. 5). Often it is easier to give good advice than to apply the same advice to personal issues and problems. Eliphaz reminded Job that his fear of God should be his confidence (v. 6; see Pr 9:10).

Again, where had Eliphaz acquired his theological information? The book of Job gives evidence of passed-down theological truths or theology in general. One needs to remember that Job, Job’s wife, Eliphaz, Bildad, Zophar, Elihu, and Job’s extended family and society, as far as is known, were not trained theologians as one would understand today. However, Job was a patriarchal priest for his household, sacrificing animals to cover and deal with human sin. This too is seen in the lives of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and later in the Israelite nation (Alden, Job, 89).

Then Eliphaz affirmed that the innocent do not perish and the upright are not destroyed (v. 7). The implications were that because Job was suffering intensely, surely he was not innocent of sin, and that God was angry with him (v. 9). Since people reap what they sow, Job was suffering the consequences of some wrongdoing (vv. 7–11). Gordis states, "Undoubtedly, Eliphaz, the most dignified and urbane of the friends, is the profoundest spirit among them; his intense religious convictions have not robbed him of sympathy for the distraught and suffering Job" (The Book of God and Man, 77). Eliphaz had a mechanical view of sin and punishment. So, since severity of sin is balanced with severity of punishment, there is no answer for Job’s situation other than some truth known only by God or based on what was the view of retribution in the ancient Near East (Alden, Job, 85–86). Eliphaz posed the problem in a rhetorical question, "If you are blameless, should you not have confidence and hope?" (v. 6). Eliphaz said Job was like a lion dying for lack of food (vv. 10–11).

4:12–21. Claiming some kind of an unusual encounter, Eliphaz lapsed into an eerie report that his answer came as a faint whisper in a night vision when a spirit approached him and said, Can mankind be just before God? Can a man be pure before his Maker? (v. 17). Alden notes, "The dreamer from Teman continued to detail the picture of his eerie vision. Lacking the words ‘goose pimples,’ Eliphaz described the same phenomenon with the rare word ‘stood on end’ [v. 16], a term that occurs elsewhere only in Ps 119:20" (Job, 87). Also, humans are less reliable than God’s angels (v. 18). When Eliphaz referred to dust in v. 19, it is likely he acquired the information to connect dust with the Maker of man and the habitation of man, not to mention the material the Maker used to create man, from Genesis (Gn 2:7). Even angels, God’s servants (possibly fallen angels and Satan), are not perfect, so certainly humans are perishable and die, yet without wisdom (v. 21).

Zuck comments on Eliphaz’s dream: "Are the words from Eliphaz’s dream true? Yes, in one sense. Man by himself cannot be righteous and pure before God; God charges man with sin more so than the angels; and man is mortal, easily perishing. However, Eliphaz seems to be wrong in applying those words to Job as if he were a willful sinner. To say ‘The reason you are perishing, Job, is that you are mortal and unclean; there is no hope for you’ runs counter to God’s evaluation of Job’s character (1:1, 8–2:3)" (Job, 33–34).

5:1–16. Eliphaz continued his diatribe against Job by hinting that he was a fool (vv. 2–3) who could not count on intervention by the angels. He then "mercilessly reminded Job of his calamities by speaking of the loss of his children and the marauding of his wealth" in vv. 4–5 (Zuck, Job, 34). Job was born for affliction (v. 6); therefore, he needed to seek God (v. 8) about his tragedies because He assists and answers the helpless (the lowly, those who mourn, v. 11, and the poor, v. 15). However, God deals with the shrewd and the wise (vv. 12–13) by confounding their schemes and cleverness.

Verse 7, For man is born for trouble, as sparks fly upward, has occasioned discussion among commentators. If it is simply a statement of the human condition as imperfect beings born in an imperfect world, then it is incongruous with Eliphaz’s view that people bring trouble on themselves by their own actions, not as a consequence of their environment (Bullock, An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books, 91). Bullock favors the view that Eliphaz was quoting a popular, pessimistic view of life that he himself did not believe; thus the idea of the verse is, "Some people say, ‘Man is born …’ " (Bullock, An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books, 91). Zuck agrees that the verse teaches that man brings trouble on himself by his sin, but adds that it is only "a partial truth," citing Jesus’ statement in Lk 13:4 that people killed by the falling tower "were no more sinful that the survivors" (Job, 34).

Concerning Jb 5:13, Alden points out, "This is the only quotation from Jb in the New Testament (with the possible exception of Job 41:11 in Romans 11:35), quoted in 1Co 3:19" (Job, 94). The apostle Paul referred to Jb 5:13 when he concluded that the wisdom of the world will not open the door for salvation. In fact the wisdom of the world will turn a person not to God but to arrogant pride.

5:17–27. Eliphaz warned Job not to despise the discipline of the Almighty (v. 17). The Hebrew word for the "Almighty" is Shaddai. As Walter C. Kaiser Jr. writes, "In the book of Job, El Shaddai is used some thirty times beginning in (5:17), and was used frequently in Genesis as a description of the God of the patriarchs [Gn 28:3; 41:14; 48:3; 49:25]. This is not unexpected, for the prologue and epilogue … have such clear credentials for placing the events of Job in the patriarchal era" (Toward an Old Testament Theology [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1978], 97).

Eliphaz’s advice to Job to endure God’s chastening instead of despising it (v. 17) was based on the mistaken assumption that Job’s troubles resulted from God’s discipline for Job’s sin. Therefore, Eliphaz’s counsel in v. 18, that Job should admit his guilt so that God could give him relief and heal him, was also incorrect.

According to Eliphaz, Job needed to remember that if he would acknowledge his sin, he would have security and need have no fear that God would heal Job’s wounds, deliver him from famine, war, violence, and abuse by wild beasts of the field (vv. 18–23). Job would also enjoy security, many descendants, and the full vigor of life (vv. 24–27). Eliphaz used the picture of a plentiful harvest to explain to Job how he would come to the grave in vigor (v. 26), "old … and full of days" (42:17), if he would only admit to his sin.

Eliphaz summarized his first discourse in v. 27. He was saying, "Friend Job, we have examined the situation, and what we are saying is true" (Alden, Job, 97). All of this blessing and healing assumed, of course, that Job would seek God (v. 8).

C. Job Responds to Eliphaz’s Charges (6:1–7:21)

6:1–13. Job’s reply to Eliphaz’s charges included a prayer to God (7:7–21) that He would forgive Job before he died from his troubles. Job actually began his reply by restating his complaint and defending the rightness of his position. He disagreed with Eliphaz, and saw his life miserably coming to an end.

Job’s grief was so heavy it was like sand (vv. 2–3). He defended his rash words (the complaint of chap. 3) by saying that they were nothing compared to the heavy weight of his grief. He perceived that the Almighty’s terrors were like poison arrows in him (v. 4). Job said he would not be complaining if he had no problem. When a donkey or ox has food, it does not bray (v. 5), so unlike them, Job is complaining with reason. His afflictions have caused him to lose his taste for life (vv. 6–7), which was now as unsatisfying as unseasoned or bland food, such as the white of an egg. "Figuratively speaking, Job found the meal that God served so unpalatable that he refused it altogether. The motif of food that began in v. 4 concludes here with Job’s total rejection of the menu. It made him sick (Jb 6:7; Ps 41:1–4)" (Alden, Job, 99).

In vv. 8–9, Job expressed the desire that God answer his prayer by killing him (crush me … and cut me off). Even though Job believed he had not denied the words of the Holy One (v. 10), he felt no strength. Zuck notes, "If God would let [Job] die, freeing him from life, Job would have one point of consolation, namely, that he did not deny God’s words" (Job, 37). Job also felt that no help or deliverance from his problems was forthcoming (v. 13). Eliphaz might have thought that Job was made out of stones and bronze so as not to feel suffering, but it was not true. To the contrary, as Alden adds concerning v. 9, "Like Moses (Nm 11:15) and Elijah (1Kg 19:4), Job wished to die" (Job, 100). The Hebrew expressions "crush" and "cut off" (Jb 6:9) often served as metaphors for death.

6:14–30. Job used the important Hebrew word translated kindness, or loyal love—the kind of loyal love and faithfulness God shows to His people—to describe the kind of response he expected from his friend. Bullock observes, "Outside of our Lord’s own bitter loneliness during His passion, there must be no keener sense of having been forsaken by one’s friends expressed in Scripture than here" (An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books, 91).

Job compared his friends to a desert wadi (a dry river bed in the summer when water was needed most) instead of a freshwater river. They acted deceitfully by pretending to help him while offering no real help, or even loyalty to him in his suffering (v. 15). Just as travelers look forward to getting water for themselves and their animals but are sadly disappointed when they find the wadis dry (vv. 17–20), so now his friends were disappointing him. He challenged them to show him where he had erred (v. 24), and even said he could stand the pain of honest words if only his friends would speak them to him (v. 25). Instead, they sought to reprove his words because they considered them worth only to blow away in the wind (v. 26).

Despite Eliphaz’s assertion that trouble comes about only as a result of sin, Job urged his friends, Now please look at me, and see if I lie to your face (v. 28). It would take a particular type of bald-faced liar to do that to his friends, and Job invited his friends to search his face for any trace of falsehood.

Assuming that they would find no such evidence, Job called on them to desist (v. 29) in their accusations—that is, to change their minds and the approach they were taking of accusing him of wrongdoing. Is there injustice on my tongue? Cannot my palate discern calamities? (v. 30) was Job’s way of saying that he would know before anyone else if his sufferings were justified. Of course, as far as he was concerned they were not, and so he did not expect a reply from his friends.

7:1–19. Starting to lose hope, Job returned to his bitter complaint as he dealt with the agony of his boil-type disease. He had devalued his existence to a state of futility and worthlessness, referring to himself as a hired man and a slave (vv. 1–2) who had been given months of vanity (v. 3). He was suffering terribly (v. 5), and he viewed his short life as swifter than a weaver’s shuttle (v. 6). Consumed in misery, he believed he would not experience any benefits again (v. 7). Since his time on earth appeared short at hand, like a mere breath (v. 7) and a cloud (v. 9), Job asked why God was constantly guarding him as if he were the sea monster (v. 12), a reference to the common ancient Near Eastern mythological beliefs held by the Canaanites and their northern counterparts in Lebanon. As Alden notes,

As in 3:8 Job again alluded to characters in popular mythology. "The sea," yam, was personalized and deified by second millennium BC Canaanites at Ugarit. The terms "monster of the deep" (Heb. tannin), Leviathan (Ugaritic Lotan; cf. 3:8; Ps 74:13–14; Is 27:1), and Rahab [not the harlot of Jericho] (9:13; 26:12; Is 51:9) were also mythological sea deities. According to the Ugaritic myth, Yam was the boisterous opponent whom Baal captured. Job protested that he was not such an unruly foe that he needed constant guarding. (Job, 111)

Job would not be silent even though he was having terrible nightmares, saying to God, You frighten me with dreams and terrify me by visions (v. 14). In his view, his death was impending. As a cloud can seem to disappear in the sky because of the intensity of the wind or sun, Job connected that observation with his apparent near demise (cf. 7:9 with 10:21 and 16:22). He would rather die than continue in his pains (7:15). God would not leave him alone long enough to swallow his saliva (v. 19), that is, for a mere second. When he is dead, he said, God will look for him but he will not be (v. 21).

7:20–21. Observing that he was physically wearing away, Job pondered whether he had sinned and why God had made him His target. Job mentioned the three classic categories of wrongdoing: sin, transgression, and iniquity. As noted in the comments on Jb 2:10, the word "sin" is chata’, which means "miss, go wrong, sin, commit a mistake, miss the mark" (BDB, 306). "In Judges 20:16 the left-handed slingers of Benjamin are said to have the skill to throw stones at targets and ‘not miss.’ In a different context, Proverbs 19:2 speaks of a man in a hurry who ‘misses his way.’ A similar idea of not finding the goal appears in Proverbs 8:36; the concept of failure is implied" (Herbert G. Livingston, "chata’," in R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer, and Bruce K. Waltke, TWOT, 277). By using this word, Job was asking God where he had missed the mark of what God wanted for him. "How have I failed to miss the way you wanted me to go?" might be one way to state Job’s perplexity.

The word transgression is pesha’, or "rebellion." The root idea is a breach of relationships between two parties. The noun denotes a person who rejects God’s authority by rebelling against it. This word suggests the need for reconciliation to remedy the rebellion. "[A]s far as God is concerned, there are two ways the rebellion may be ended; it may end with punishment or the renewal of the relationship (Livingston, "chata’," 743)." Job did not use transgression in a question (7:21). Instead, he was saying, "God, if I have rebelled against You, why have You not forgiven me?" As Zuck states the issue, "Why all the big the fuss about a little sin—if I have even sinned at all?" (Job, 42).

Job’s third word for sin (v. 21) is ‘awon, or "iniquity." The noun form used here refers to "infraction, crooked behavior, perversion, iniquity, etc.… ‘awon is definitely not a trait of God’s character nor of his dealing with man … but it is an overwhelming trait of man’s character and actions, including consequences of those actions" (Carl Schultz, "‘awon," TWOT, 650). Although Job was not aware of committing iniquity, any more than he was aware of missing the mark or rebelling against God, he asked why God had not forgiven and removed his iniquity and its guilt.

Job wondered if he had violated all three categories of sin at once. Or had he crossed an invisible line into an unknown category of sin? He was disillusioned by the growing influence of evil on his life, his family, his reputation, his work, and his theology. In asking, Have I sinned? (v. 20), Job was grappling with the massive issue of sin. What is sin? Is it negative actions, negative thinking, the absence of good, the lack of education, the lack of understanding? Is it simply a human issue? Is sin an issue people can deal with strictly on a human level? Very simply, sin is any thinking or activity that is contrary to the character of God and the boundaries He has established.

D. Bildad Delivers His First Speech (8:1–22)

8:1–14. Job ended his lament in chap. 7 with the statement, "For now I will lie down in the dust; and You will seek me, but I will not be" (v. 21). His complaint and questioning of God brought a stinging rebuke from one of his visiting friends, Bildad, who is identified as a Shuhite (v. 1). In cuneiform tablets, an area near the Euphrates River is called Suhu. Some see Bildad as a member of the tribe named for Shuah, the son of Abraham and Keturah (Gn 25:2). Bildad addressed Job’s turmoil and responded in a much harsher tone and attitude than did Eliphaz.

As did Eliphaz, Bildad believed that a person’s calamities result from his or her sins. Bildad also echoed Eliphaz in saying that Job might be able to recover from his woes if only he would acknowledge his sin. But in contrast to Eliphaz’s appeal to personal experience ("I have seen," 4:8) and his dream (4:12–21), Bildad appealed to the experience of previous generations in this speech. And while Eliphaz began his first speech with a question that was "soft and courteous … Bildad’s opening query was blunt and discourteous" (Zuck, Job, 43).

Bildad directly stated that Job harbored perverted ideas about God’s justice, for apparently his children got what they deserved (vv. 1–4). Bildad was angry at Job’s insistence on his innocence, his expressed frustration with his three friends, and his statements that God was hounding him despite his lack of wrongdoing. Bildad was also apparently upset that Job had rejected Eliphaz’s gentle rebuke. He characterized Job’s defense to Eliphaz in chaps. 6–7, as just a mighty wind (v. 2) producing nothing of value. In v. 3, Bildad strongly argued that if Job’s accusations about God were true, then that would make God unjust since He would be afflicting one who did not deserve it (cf. 40:8). The only explanation for the death of Job’s children was that God delivered them into the power of their transgression (v. 4)—a charge that must have wounded Job deeply. But as far as Bildad was concerned, if God is God as presented by Job and his friends in this theological debate, then the only conclusion anyone could come to was that Job must be the one who is wrong.

Bildad then confronted Job, maintaining that his sin must had to be the cause of the death of his children. Alden notes, "The most cruel and least tactful part of Bildad’s confrontation is just a restatement of the basic theology of retribution that the three friends held to so tenaciously" (Job, 116). Bildad told Job to seek God and if he did, God would restore his estate (vv. 5–7). Bildad also encouraged Job to seek the sound wisdom of past generations (v. 8) and not to forget it because one’s life is like a mere shadow (v. 9). Bildad directed Job to consider a body of truth handed down from former generations. Apparently Bildad believed that truth and wisdom were not limited to their generation. His statement that Job would learn from past generations by studying the words from their minds may have been Bildad’s way of "sarcastically hinting that Job’s words were from his mouth only [v. 2] and not from his mind" (Zuck, Job, 44).

These statements by Bildad also help to place these events in history. They reflect what Alden calls "well-established, long-held wisdom," and adds, "While former generations have passed away, their accumulated wisdom remains, and to that old wisdom Bildad made his appeal" (Job, 118–19). Bildad seems to have had Job in mind when he referred to all who forget God and are godless. They are like a papyrus plant withering without water (vv. 11–13). The confidence of such people is as fragile as a spider’s web (v. 14).

8:15–22. Job had no respite from Bildad’s accusations. The latter said the wicked person trusts in his house, but it does not stand—perhaps suggesting that Job was trusting in his estate as his confidence. Bildad also suggested that Job was like a thriving plant that was then uprooted (vv. 16–18), to be replaced by other plants (v. 19). But God honors people of integrity (v. 20). If Job were to repent, God would enable him to laugh and the wicked would be abolished (vv. 21–22).

E. Job Responds to Bildad’s Charges (9:1–10:22)

9:1–12. Now it was Job’s turn to respond to Bildad’s withering attack. Despite the searing nature of the latter’s charges against him, Job replied, I know that this is so, that is, that evil people are cut off from before God (v. 2). "All bad things that happened to the world or to people were viewed as expressions of God’s anger" (Alden, Job, 127). Job and his friends initially assumed that God always punishes evil. But knowing this, the question for Job was, But how can a man be in the right before God? Eliphaz had asked virtually the same question in his first speech: "Can mankind be just before God? Can a man be pure before his Maker?" (Jb 4:17). Job’s dilemma was that even if he had his "day in court" before God, there was no answer he could give to the One who could remove mountains, shake the earth, and command the sun not to shine (vv. 3–7).

Furthermore, Job argued that since God created the constellations, how would he even know if God passed by him, or how could he know if it was God’s voice since He is so powerful that He created the Bear, Orion and the Pleiades (v. 9; cf. 38:31–33). Later in biblical history the prophet Amos affirmed that it was God who made the Pleiades and Orion (Am 5:8). S. C. Hunter noted, "The writer of the book of Job seemed to have a surprising familiarity with celestial matters" ("Bible Astronomy," Popular Astronomy 2 [1912]: 288). As Alden points out, "All these references to the world around—sun, stars, sea, heaven, and earth—attest to Job’s monotheism. Unlike the neighbors of ancient Israel, who attributed each of these domains to separate deities, Job and all the Bible’s authors believed that God alone was responsible for their creation and regulation" (Job, 125). In chaps. 9 and 10 Job defended his conclusions to Bildad by noting God’s magnitude in creation (W. D. Reyburn, A Handbook on the Book of Job [New York: United Bible Society, 1992], 781–83).

In v. 10, Job again recalled the words of Eliphaz, quoting almost verbatim the latter’s statement concerning God, Who does great and unsearchable things, wonders without number (Jb 5:9 HCSB). Job asked, "In the face of a God like this, whose power is unfathomable, and who does whatever He pleases, how could I possibly expect to win my case against Him?"

9:13–24. Job described God’s power as being so great that He conquered the helpers of Rahab (v. 13; cf. Ps 89:10; Is 51:9). This reference is to a sea monster in Babylonian myth who was defeated by Marduk, who then captured her helpers (Zuck, Job, 48). Rahab is another name for Leviathan, the sea monster of Jb 7:12. God’s power is so great that He can defeat all the forces of evil, real or mythical.

How, then, could Job expect to present a case before such an Almighty (and seemingly aloof) God and expect to even be heard, much less vindicated? Job realized his only hope was to throw himself on the mercy of his judge, regardless of the merits of his plea that he was, after all, right in his claim of innocence (vv. 14–16). Job was not confident that God would listen to him, even if He called on Job to speak. As Zuck notes, "God is so overwhelming, Job argued, that he was afraid he would become confused and witness against himself (9:20)!" (Zuck, Job, 49). Job’s righteous position would count for nothing in the court of heaven.

There was only one understandable conclusion from Job’s standpoint: God destroys the guiltless with the wicked, even though that seems to be a great theological contradiction (v. 22). Alden notes, " ‘Innocent/blameless’ and ‘wicked’ are words laced throughout this portion of Job’s complaint (vv. 20–24). The two are opposites, but not to God, fretted Job (cf. Matt 5:45). They are one and the same.… That God destroys the wicked would be affirmed by Job’s friends, but that he treats the godless and the godly alike is what separated Job’s position from theirs (cf. Mal 3:18)" (Job, 130).

9:25–35. Sensing his life was slipping away (vv. 25–26), Job resolved to try to forget his troubled circumstances. But he knew this would be useless because his pain would make him sad again, and he knew that God would not acquit him (vv. 27–28). Job longed for an umpire to arbitrate between God and himself in a court (v. 33). Walter C. Kaiser Jr. maintains that this is the first hint of messianic expectation in Job. A mediator between God and a human being could not be a mere mortal but had to be divine. "One can see the logic building for some person who will be no less than the Son of God if he is to bridge the gulf created by this situation" (Walter C. Kaiser, The Messiah in the Old Testament [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1995], 62). And as Alden adds,

Job also used other terms to describe his need for someone to come to his aid: "arbitrator" (9:33); "witness, advocate," (6:19); "intercessor, friend," (16:20); and, "redeemer" (19:25). The Christian reader of these passages cannot help but think that the one Job sought for has come to us in Jesus Christ (Compare Lk 1:74; Rm 7:24; Gl 1:4; 2Tm 4:18; 2Pt 2:9). (Alden, Job, 136–37)

This section emphasizes Job’s struggle with understanding the reason for his suffering. As Smick notes, "the text hints at some unknown reason for Job’s suffering above and beyond the dispute over Job’s motives described in the prologue.… Neither Job’s friends nor his readers are truly able to access fully the reason for his suffering" ("Job," 263). Ancient and modern-day believers in the Lord must remember that suffering serves a spiritual purpose. At times, God chooses to bring believers to spiritual maturity through suffering, to help strengthen their integrity toward Him. Paul testified to this when he declared, after asking God three times to remove his "thorn in the flesh" … "Most gladly, therefore, I will rather boast about my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may dwell in me" (2Co 12:7, 9).

Yet, at other times God permits suffering to bring glory to Himself. The blind man of Jn 9 illustrates this truth. To the disciples’ Job-like question, "Who sinned, this man or his parents, that he would be born blind?" (v. 2), Jesus replied, "It was neither that this man sinned, nor his parents; but it was so that the works of God might be displayed in him" (v. 3). The ultimate explanations for suffering are in God’s hands.

10:1–7. Job pleaded with God to tell him why He was contending with him in this severe manner, because based on Job’s knowledge of the true God, he had not changed his lifestyle or relationship since the time when he abundantly prospered—and God knew that (v. 7).

Therefore, Job challenged God with a series of questions in an attempt to discover why God was afflicting him. Job’s first question implied that God was acting unjustly by punishing Job, whom He had created, while looking favorably on the schemes of evil men (v. 3). Perhaps God was even acting like a finite human being, like someone who was limited in his lifespan and knowledge and so had nothing to go on but the eyes of flesh and the days of a mortal (vv. 4–6). Job accused God of knowing that he was not guilty of any behavior worthy of such calamity, and yet Job experienced no deliverance from [God’s] hand (v. 7).

10:8–17. Job reflected on the marvels of how God fashioned him in the womb and made him from clay and dust (cf. Gn 2–3). Yet, God also seemed intent on destroying this marvelous work of His hands. Why would God create Job so intricately only to destroy him (v. 8)? Job reminded God that He made Job out of the dust into a clay pot. Was it God’s plan to smash Job into dust again? (v. 9). The questions continued in vv. 10–11 as Job described his creation by God’s hand. Job also remembered how God showed him lovingkindness (lit., "loyal love," v. 12).

But it seemed that all the while, even from the moment of Job’s creation, God had planned the calamities that befell Job—and therefore, Job felt that he was justified in holding God accountable for his suffering. He proposed that perhaps it made no difference with God whether he was wicked or righteous (v. 15). He felt that God opposed him like a lion, showing Job His power and anger. Not only that, but even if Job were given his day in court, God would gather more witnesses against him and only become angrier with him. No wonder Job felt as if he was experiencing one hardship after another (vv. 16–17).