JUDGES

John McMath

INTRODUCTION

The book of Judges continues the historical narrative of the people of Israel in the land after the death of Joshua to the beginning of the united kingdom under the ministry of Samuel.

The book is called shophetim in Hebrew, Kritai in the LXX, and Liber Iudicum in the Latin Vulgate. In all three languages these words mean "judges." The English "Judges" follows this tradition.

Although the judges did sometimes decide civil disputes (e.g., Deborah), their major function was political and military leadership.

The Hebrew root sh-ph-t for "judge" probably derives from a Semitic term with a semantic range including "ruling and controlling," as well as "correcting," "putting in order," or "making just." The book of Judges also emphasizes the empowerment of the Spirit of God. This "filling" of the Spirit has led many commentators to note that the judges reveal God’s work of specially gifting people for God’s work. While there are parallels to the political functions of the judges in Mesopotamia and in Carthage, and even in ancient Ebla, the divinely empowered status of the Israelite judges appears to be unique in history.

Author. Who wrote Judges is unknown. Critics have pointed to the obvious three-part structure of the book (see the outline) as evidence for a complicated tradition history. But such a hypothesis is unnecessary. The central point of the book, that even divinely empowered human leaders cannot lead Israel to spiritual triumph, is well served by the structure of the book. The commentary will assume that the book is the work of a single author.

The author of Judges used sources, as all historians do. The story of the wars of occupation (1:1–2:5) may have been a parallel account to the Joshua story (with some significant differences of emphasis). The appendix (chaps. 17–21) may have come from other hands. Certainly the Song of Deborah (chap. 5) was ancient by the time the final author included it in the book. The stories of the individual judges may have come from separate sources. However, a single author put the material into its canonical form under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

The Talmud attributes the authorship of Judges to Samuel. The major argument against this view, however, is that the book seems to be an argument for a king, whereas Samuel seems to have opposed the idea. Those who favor Samuel’s authorship of Judges say that he opposed, not so much the idea of a king, as the Israelites’ motivation for seeking a king. The people saw a king as a solution to their immediate political and military problems, and Samuel saw a godly king as a representative of the King of kings. Samuel may have written the book as a polemic against mere human kingship, since even the divinely empowered leaders failed. Ultimately, the work was designed to be anonymous and should be read that way.

Date. Several clues point to the conclusion that the author of Judges wrote during the early years of the monarchy. First, the hectic days of the judges appear to be viewed from a more stable and secure position. Second, Jdg 1:21 points to a time before David’s capture of Jerusalem when the "Jebusites … lived with the sons of Benjamin … to this day." Third, 1:29 reports Canaanite control of Gezer, a major site about 20 miles west and slightly north of Jerusalem on the international trade route at the entrance to the Aijalon Valley. Not until later (in 970 BC) did Gezer come under Israelite control.

The note of 18:30, that the idolatrous priests of Micah continued to serve "until the captivity of the land" has led some critics to insist on a postexilic date for the writing of Judges. However, it is unlikely that such a dreadful situation would have been allowed during the years of David and Solomon. E. J. Young’s suggestion (in An Introduction to the Old Testament [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1949]) that "land" should read "ark" (so that the verse refers to the Philistine capture of the ark of the covenant in about 1075 BC), makes good sense, and requires only a minor change of the consonants (‘arets to ‘aron). However, there is no manuscript support for this, and modern scholars have generally not accepted that idea.

Themes. The key to understanding the work of the judges appears in 2:16: "The Lord raised up judges who delivered them from the hands of those who plundered them." "Delivered" is the common verb meaning "to save." This is ironic, for Moses was sent to deliver the people from Egypt, and ended up presiding over funerals in the wilderness for 38 years. Joshua, whose name means "Deliverer" or "Savior," succeeded only partially in delivering the people. The apparent motivation for the writing of the book of Judges is the recurring failure of the judges to deliver the people. This theme occurs twice in the book: "In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did what was right in his own eyes" (17:6; 21:25). That even divinely empowered human leaders could not lead Israel to spiritual triumph points to the need for a great King beyond even Saul and David. The term "great King" is a Near Eastern concept, first applied by the Hittites, of a "king above the kings," or leader of an empire. In the context of Israel in the time of the judges, the term "great King" refers to the messianic leader who alone can fulfill the needs of mankind.

Purpose. The book of Judges continues the history of Israel, bridging the years between the conquest and the rise of the monarchy.

But, in addition, the author was building a case for the need for a great King. In doing so he demonstrated the downward trend of the spiritual condition of Israel over the centuries of the judges, arguing that temporary and local leaders could not provide a solution for the underlying problems the people of Israel faced. Genuinely impressive victories under Deborah and Barak and then Gideon were followed by the nation’s collapse again into sin and idolatry. The later judges Samson and Jephthah gave only limited respite from anarchy. Chapters 17–21 show a period of history in which the people of Israel increasingly slid into apostasy. The location of these chapters in the book may not be chronological, but the intention is clear: to give the reader a bad portrait of Israel without God as their King.

Background. Judges is included in the larger corpus of material often called the "Primary History"—Pentateuch, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, Ezra-Nehemiah—all probably written by prophets, and distinguished from the chronicler’s history. This constitutes a well-planned metanarrative behind the entire history of Israel, written by multiple authors who used a wide variety of literary sources from about 1500 to 400 BC.

In this larger historical framework the story of heroes and prophets, deliverers and judges, kings and conquerors is one of frequent tragedy. Moses, the man of God, was unable to enter the promised land. Joshua, the conqueror, was unable to lead the people to nearly complete victory over the land of Canaan. Judges, one after another, staved off defeat for decreasing periods of time. Saul was a failure. David committed adultery with Bathsheba and had her husband Uriah murdered. Solomon acquired numerous wives and horses, and slid into idolatry. Many of the kings of Israel and Judah were a rogues’ gallery with occasional bright moments on the way to the increasingly predictable destruction of the kingdom.

The metanarrative, then, tells a broader story, of which Judges is merely a part. Biblical theologians speak of the "center" or "theme" of biblical theology. From Genesis to Revelation the Bible is designed to reveal God in His glory. For this overarching glory of God, two great parallel themes develop: the kingdom program and the redemption program, intertwined from Gn 3:15 (the "protoevangelium"; see the comments there) to eternity.

The author of Judges despaired of the possibility of a mere earthly kingdom providing the foundation for lasting godliness. God knew that no earthly king could ever solve Israel’s problems. The massive sin problem of mankind demands a King who is also the Redeemer.

For this reason it is best to see the metanarrative of the primary history as a messianic prelude. The messianic "seed" predicted in Gn 3:15 and followed through the kingly line is picked up by the prophets as the great King who would suffer for sin and ultimately rule on the earth and in heaven for all eternity.

The King who was "not in Israel" (Jdg 18:1) in the time of the judges was not merely a temporal head of state. The great King is Messiah the Prince, Jesus Christ. Judges is then part of an overall biblical narrative with a trajectory pointing to Christ and eternity. Jesus, whose name is the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew "Joshua," is the great "Deliverer."

The period from the death of Joshua to the establishment of the monarchy was roughly 300 years. Judges recounts the turmoil of the tribes during the years following the failure to occupy the land completely. The surrounding world was also in turmoil. Significantly, the Egyptians were in disarray during the Amarna Age (15th century BC), followed by the resurgence of the Nineteenth Dynasty pharaohs Ramses II and Mernepthah. The Hittites were in mortal confrontation with the Mesopotamian Mitanni, and minor regional powers jockeyed for position. The Philistines, part of a larger Aegean people group sometimes called "Sea-Peoples," were migrating into the region during this period, and posed a threat to Israel.

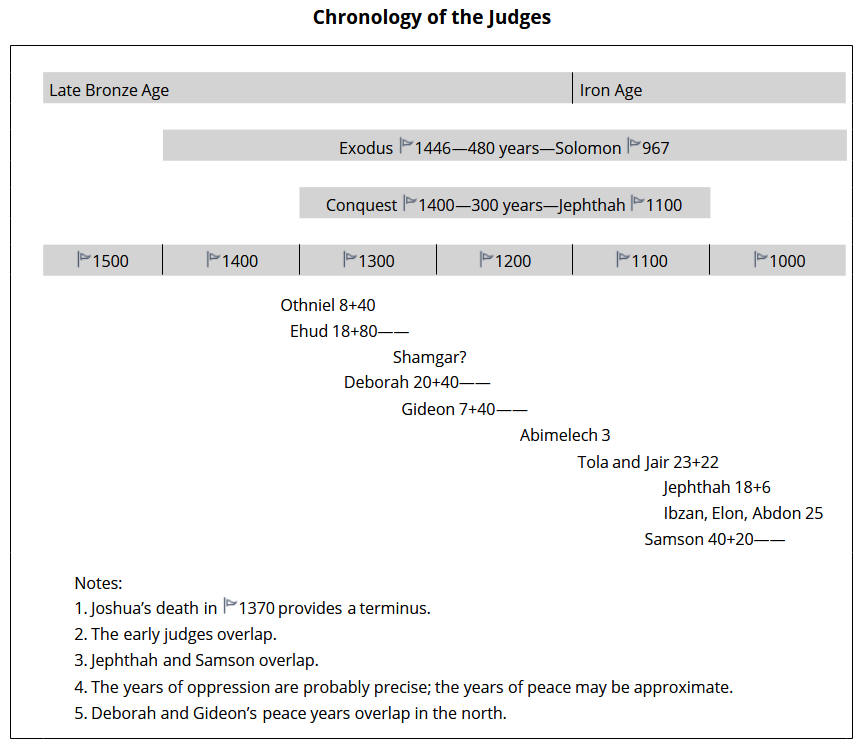

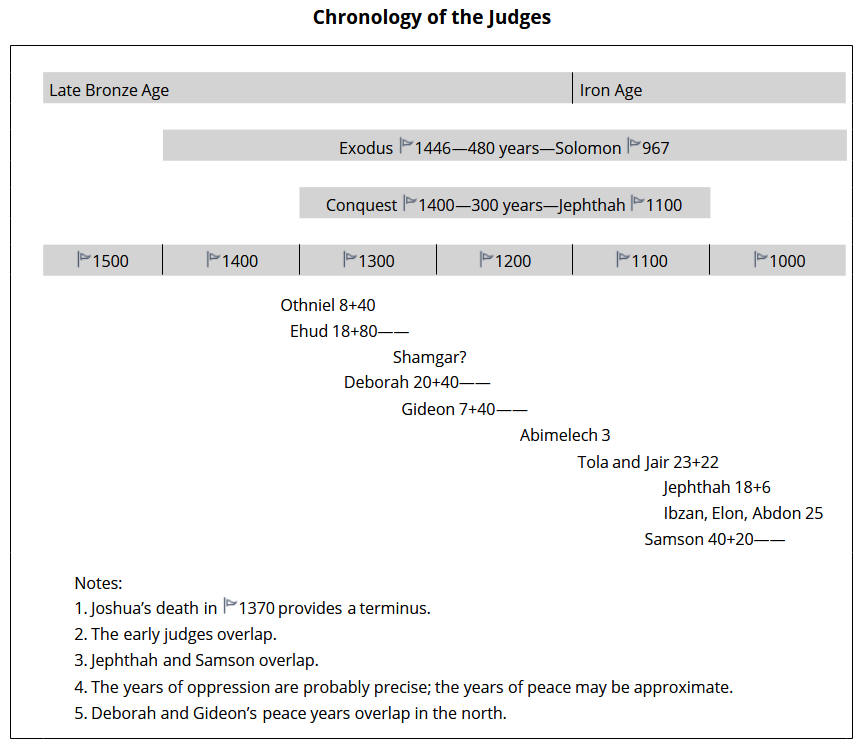

The years of the judges’ rulership and the years of rest, when added together, comes to a total of between 410 and 490 years. Most interpreters allow for an overlapping of judgeships to account for this chronological problem. Samson and Jephthah, for example, were possibly contemporaries, with Samson in the West and Jephthah in the East.

Most conservative scholars believe the exodus occurred in 1446 BC, and the conquest under Joshua was from 1405 to 1400. In Jdg 11:26 Jephthah indicated that Israel had occupied the region of Heshbon and Aroer for 300 years. Since Jephthah (and Samson) were at the end of the line of judges, this means the period of the judges extended from about 1400 to at least 1100. The period may have extended another 49 or 50 years (for a total of 349 or 350) because Saul began his reign in 1051. Or more likely, the period of the judges may have begun in 1351 and ended 300 years later in 1051.

The book of Judges is a story of warfare, assassinations, treachery, and general mayhem. Ehud’s secretive stabbing of Eglon, Jael’s tent-peg exploit, and Gideon’s execution of the kings all may seem somewhat less than ethical today. In many ways the treatment of these issues is like that of the imprecatory psalms (e.g., 109:6–13) in which the enemies of Israel are viewed as the enemies of God, and their cruel punishment is a means of glorifying God.

Some of the judges, however, are particularly distasteful. Samson and Jephthah raise the question, "How can a good God use evil men?" The answer is that God’s judgment is often carried out in political and military movements. In this way the Babylonian invasion was explained to Habakkuk and the coming of Cyrus, king of the Persian totalitarian empire, was extolled as God’s servant in Is 44–45.

Perhaps these ethical shortcomings are a part of the argument that human deliverers will always fall short of the perfection that people expect and desperately need.

The following outline of Judges assumes that a single author used his literary art to put existing historical materials into a coherent frame. The dual prologue is matched by a parallel pair of epilogues framing 12 stories of deliverers. The prologues explain the historical failure and theological basis of the period. The list of judges is divided into two parts; the early judges were generally helpful, and the later ones were much less sympathetic. The epilogues graphically portray the tenor of an age when every man did what was right in his own eyes.

OUTLINE

I. Two Prologues: Israel’s Partial Obedience after Joshua’s Death Leads to a Cycle of Sin and Grace (1:1–3:6)

A. An Account of Obedience and Failure (1:1–2:5)

1. Stage Setting (1:1)

2. Faithful Judah (1:2–21)

3. Failure of the Northern Tribes (1:22–36)

4. Israel’s Lament (2:1–5)

B. The Theology of Sin and Grace (2:6–3:6)

1. Account of the Death of Joshua and the Aftermath (2:6–10)

2. Account of the Idolatry of Israel (2:11–13)

3. God’s Anger Displayed in the Rise of Oppressors (2:14–15)

4. The Judges Raised Up as a Respite from Oppression (2:16–19)

5. God’s Anger at Covenant Transgression Resulted in Pagan Nations that Could Not Be Driven Out (2:20–23)

6. Nations Left to Test and to Punish (3:1–6)

II. Twelve Deliverers Demonstrate a Cycle of Increasing Failure (3:7–16:31)

The Early Judgeships:

A. Othniel: The Model of the Judges Cycle (3:7–11)

1. Israel’s Sin of Idolatry (3:7)

2. Israel Sold into Mesopotamian Oppression for Eight Years (3:8)

3. Heartfelt Cry for Deliverance (3:9a)

4. A Deliverer Raised Up: Othniel, Son of Kenaz (3:9b–10)

5. Forty Years of Rest (3:11)

B. Ehud: The Left-Handed Judge (3:12–30)

1. Eighteen Years under Eglon of Moab (3:12–14)

2. Ehud’s Clandestine Mission (3:15–24)

3. Slow Response of Eglon’s Servants (3:25)

4. Ehud’s Escape and the Muster of Ephraim (3:26–30a)

5. Eighty Years of Rest (3:30b)

C. Shamgar: An Enigmatic Interlude (3:31)

D. Deborah: A Mother in Israel (4:1–5:31)

1. The Military Campaign against Hazor (4:1–24)

a. Twenty Years under Jabin of Hazor (4:1–3)

b. Deborah the Prophetess Called on Barak the Soldier (4:4–10)

c. Heber the Kenite Introduced (4:11)

d. The Battle of the Kishon (4:12–16)

e. Sisera Meets Jael (4:17–22)

f. The Long Campaign against Jabin (4:23–24)

2. The Song of Deborah (5:1–31)

a. Call to Praise the Lord (5:1–5)

b. Deborah’s Motivation, as a Mother in Israel (5:6–11)

c. The Muster of the Tribes (5:12–18)

d. The Battle at the Kishon (5:19–23)

e. Jael: Most Blessed of Women (5:24–27)

f. Lament of Sisera’s Mother (5:28–31a)

3. Forty Years of Rest (5:31b)

E. Gideon: A Lesser Son of a Lesser Son (6:1–9:57)

1. Introduction to the Gideon Episode (6:1–10)

a. Seven Years of Oppression by Midian (6:1–6)

b. The Covenant Message of a Prophet (6:7–10)

2. Gideon’s Call to Deliver Israel (6:11–40)

a. Gideon Called by the Angel of the Lord (6:11–18)

b. Gideon’s Presentation and Fear (6:19–24)

c. Hacking the Altar and Asherah (6:25–27)

d. Confrontation with Joash (6:28–32)

e. Muster of the Northern Tribes (6:33–35)

f. Sign of the Fleece (6:36–40)

3. The Defeat of Midian (7:1–25)

a. The Camp at Harod (7:1)

b. The Selection of the Fearless (7:2–3)

c. The Selection of the Unobservant (7:4–8)

d. Gideon Overheard a Dream (7:9–14)

e. Preparation for the Battle (7:15–18)

f. The Battle on the Plains of Esdraelon (7:19–23)

g. The Muster of Ephraim (7:24–25)

4. Aftermath of the Battle (8:1–27)

a. Appeasement of Ephraim (8:1–3)

b. No Help from Succoth and Penuel (8:4–9)

c. Capture of Kings; Routing of Midian (8:10–12)

d. Punishment of Succoth and Penuel (8:13–17)

e. Execution of Zebah and Zalmunna (8:18–21)

f. Gideon Offered the Kingdom (8:22–27)

5. The Era of Gideon’s Rest (8:28–35)

a. Forty Years of Rest (8:28)

b. Gideon’s Later Life and Descendants (8:29–32)

c. Israel Forgets the Lord (8:33–35)

6. Abimelech and the Fall of Shechem (9:1–57)

a. Abimelech’s Treachery and Jotham’s Response (9:1–21)

(1) Abimelech Conspired to Become King of Shechem by Treachery (9:1–6)

(2) Jotham’s Fable (9:7–15)

(3) Jotham’s Challenge and Escape (9:16–21)

b. The Fall of Shechem and Abimelech (9:22–55)

(1) Three Turbulent Years of Rule (9:22–25)

(2) Gaal, the Challenger (9:26–29)

(3) Zebul, the Lieutenant, Warned of Treachery (9:30–33)

(4) The Defeat of Gaal (9:34–41)

(5) The Capture of Shechem (9:42–45)

(6) Burning the Tower of Shechem (9:46–49)

(7) Death of Abimelech at Thebez (9:50–55)

c. Fulfillment of the Curse of Jotham (9:56–57)

The Later Judgeships:

F. Tola and Jair: Two Minor Administrators (10:1–5)

1. Tola: Twenty-Three Years of Stability (10:1–2)

2. Jair: Twenty-Two Years of Prosperity (10:3–5)

G. Jephthah: Outcast Deliverer (10:6–12:7)

1. Gilead and the Challenge of Ammon (10:6–18)

a. Sin and Affliction for 18 Years (10:6–9)

b. Supplication until God Could Not Bear It (10:10–16)

c. The Muster of Ammon and Gilead (10:17–18)

2. Jephthah Called to Face Ammon (11:1–11)

a. Jephthah Introduced (11:1–3)

b. Jephthah Agreed to Lead Gilead (11:4–11)

3. The Battle of Ammon (11:12–40)

a. Jephthah’s Diplomacy (11:12–28)

b. Jephthah’s Foolish Vow (11:29–33)

c. Jephthah’s Daughter (11:34–40)

4. Civil War with Ephraim (12:1–6)

5. Six Years of Rest (12:7)

H. Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon: Three Minor Administrators (12:8–15)

1. Ibzan: Seven Years a Family Man (12:8–10)

2. Elon: Ten Years in Zebulun (12:11–12)

3. Abdon: Eight Years with Donkeys (12:13–15)

I. Samson: A Deeply Flawed Deliverer (13:1–16:31)

1. Forty Years of Philistine Oppression (13:1)

2. Conception and Birth of a Remarkable Boy: Samson Introduced (13:2–25)

a. The Angel of the Lord Appeared to Manoah’s Wife (13:2–7)

b. Manoah Spoke with God (13:8–14)

c. Sacrifice before the Angel of the Lord (13:15–20)

d. Common Sense of Manoah’s Wife (13:21–23)

e. Samson’s Birth and Divine Empowerment (13:24–25)

3. Samson’s Marriage at Timnah (14:1–15:20)

a. Samson Chose a Wife from the Philistines (14:1–4)

b. Samson Took His Parents to Meet the Girl (14:5–9)

c. Samson’s Wedding Debacle (14:10–20)

(1) The Feast (14:10–11)

(2) Samson’s Riddle (14:12–14)

(3) Treachery on Treachery (14:15–20)

d. Samson’s Destruction of Philistine Crops (15:1–8)

e. Samson Submitted to the Men of Judah (15:9–13)

f. The Battle of Lehi (15:14–19)

g. Twenty Years of Samson’s Leadership (15:20)

4. Samson’s Lust and Death (16:1–31)

a. Samson and the Harlot of Gaza (16:1–3)

b. Samson and Delilah (16:4–22)

(1) Delilah Introduced (16:4–6)

(2) Three Tests of Strength (16:7–14)

(3) Delilah Extracted the Secret of Samson’s Strength (16:15–17)

(4) Samson Captured by the Philistines (16:18–22)

c. Samson’s Humiliation and Vengeance (16:23–31)

(1) Samson’s Humiliation (16:23–27)

(2) Samson’s Vengeance (16:28–31)

III. Two Epilogues: The Abominable Spiritual Condition of Israel Called for a Great King to Stabilize and Lead the Nation (17:1–21:25)

A. The Idolatry of Dan (17:1–18:31)

1. Idolatry in Ephraim (17:1–13)

a. Micah and His Mother (17:1–6)

b. A Levite for a Priest (17:7–13)

2. Danites on the Move (18:1–31)

a. Danite Patrol Meets the Priest of Micah (18:1–6)

b. Danites Find a New Place to Settle (18:7–10)

c. Journey of the Six Hundred to Ephraim (18:11–13)

d. Subversion of Micah’s Priest (18:14–20)

e. Confrontation with Micah (18:21–26)

f. Establishment of Idolatry in Dan (Laish) (18:27–31)

B. The Perversion of Benjamin (19:1–21:25)

1. Degrading Murder of a Levite’s Concubine (19:1–30)

a. A Levite Fetched His Concubine in Bethlehem (19:1–9)

b. Journey to Gibeah (19:10–15)

c. Kindness of a Stranger in Gibeah (19:16–21)

d. Perversion of the Men of Gibeah Leads to Rape and Murder (19:22–26)

e. Grisly Summoning of the Tribes (19:27–30)

2. Resolution to Punish the Guilty (20:1–17)

a. Muster of the Tribes at Mizpah (20:1–7)

b. Agreement to Punish Benjamin (20:8–11)

c. Deployment of Benjamin and All Israel (20:12–17)

3. Civil War and Benjamin’s Defeat (20:18–48)

a. Inquiring of the Lord (20:18)

b. First Failed Attack (20:19–23)

c. Second Failed Attack (20:24–28)

d. Third Attack and Success by Ambush (20:29–48)

4. Reconstitution of a Lost Tribe (21:1–24)

a. Dilemma for the Tribes of Israel (21:1–7)

b. Destruction of Jabesh-Gilead (21:8–12)

c. Gift of Wives to Benjamin (21:13–15)

d. More Wives from Shiloh (21:16–24)

5. The Refrain: No King in Israel (21:25)

COMMENTARY ON JUDGES

I. Two Prologues: Israel’s Partial Obedience after Joshua’s Death Leads to a Cycle of Sin and Grace (1:1–3:6)

The prologues illustrate the historical failure of the tribes, even with the best of intentions, to capitalize on the efforts of Joshua. The reasons for this failure are ethical and theological. The people of Israel forgot the Lord and began to live as though He does not exist. The only real solution to the sin principle in the nation is the grace of God.

A. An Account of Obedience and Failure (1:1–2:5)

This first prologue includes details that parallel portions of the book of Joshua, thus building a context for the spiritual failure recounted in the second prologue. That the Canaanite population was allowed to remain in significant enclaves led to the downfall of the nation.

1. Stage Setting (1:1)

1:1. The phrase after the death of Joshua forms the context for the entire book. The people asked the Lord who should be first to go up and fight against the Canaanites who were still living in the land. The miracle-marked leadership of Moses and Joshua was over, and no clear leadership had yet arisen. No God-ordained and empowered leadership of the nation was in sight. Joshua’s death is reported again at the beginning of the second prologue (2:8; cf. Jos 24:29).

2. Faithful Judah (1:2–21)

The listing of tribes in this prologue is not exhaustive, but moves generally from south to north, beginning with Judah.

1:2. God responded to Israel’s inquiry that Judah should go up first against the Canaanites. Judah’s alliance with Simeon is reported in these verses as the beginning of continued efforts to rid the land of the Canaanites. These events are to some extent paralleled by the account in Jos 15–17.

1:3–5. The Canaanites generally represent all the native people of the land. The word Perizzites is related to "village life" (Hb. perazon in 5:7). Thus the Perizzites were the village dwellers, that is, peasants living in unwalled settlements in the hill country, and the Canaanites were occupants of the cities.

Ten thousand men were defeated. A continuing problem in OT studies is the large numbers often reported. Most scholars agree that the population and army deployment sizes, as well as the numbers killed in various encounters, are improbably large. Expositors have suggested a variety of explanations, but none solves all the problems. The best solution involves attempts to understand the Hebrew eleph, traditionally translated "thousand." If an eleph is understood as a "company," "clan," or "army unit," some problems are eased, but others are made worse. It is better not to be dogmatic about the numbers.

1:6–7. The defeat of Adoni-bezek ("Lord of Bezek") is difficult to locate geographically. Bezek is also mentioned in 1Sm 11:8 as the place where Saul assembled an army. The ruin of Khirbet Bezqu northeast of Gezer, which is about 20 miles northwest of Jerusalem, may preserve the name.

The severing of thumbs and big toes was a means of humiliating the severely defeated kings. Adoni-bezek admitted that he had done the same to his own foes, so he deserved no mercy. The humiliation and mutilation of royal prisoners was not unusual in ancient Near Eastern warfare. While no example of the severing of thumbs and toes is evident in ancient monuments, many reliefs show prisoners bound, kneeling, and mutilated. Also heaps of hands are common in the Egyptian monuments.

1:8. Jerusalem does not refer to the Jebusite fortress in the tribal allotment of Benjamin, which the Benjamites could not take (v. 21). Instead this is the unfortified western hill, known today as Mount Zion, outside the wall that now contains the Jewish and Armenian quarters of the modern old city Jerusalem. Few remains in this area can be dated to the Late Bronze Age except for a few potsherds.

1:9–15. Judah defeated the Canaanites in the Negev in Hebron and Kiriath-sepher. The Negev is the southern arid region of Israel. Hebron is about 20 miles south of Jerusalem, and Kiriath-sepher, also called "Debir," is about 10 miles southwest of Hebron.

1:16–17. Moses’ father-in-law, Jethro, was a Kenite and a priest of Midian (Ex 18:1). His priesthood was related to the general revelation priesthood of Melchizedek (see the comments on Gn 14). The Kenites were apparently a nomadic Semitic people living in the Sinai area. Their transplantation to the Negev indicates a uniting of spirit with Israel. Apparently a monotheistic tradition among nomadic people existed in the desert from the earliest times. The exact locations of Arad, Hormah, and Zephath are difficult to know. Hormah means "ruin" and could easily be a commemoration of Israel’s destruction of the place. Zephath probably means "lookout" and may originally have been associated with a high spot nearby.

1:18. The men of Judah took three Philistine cities: Gaza … Ashkelon … and Ekron. This makes some sense only if the Hebrews’ conquest and settlement of the land was taking place during the Late Bronze II Age (1400–1200 BC). If the Judges period came later, during the time of Philistine dominance in the region, this note would be ludicrous. The coastal plain, from Gaza to Dor, was occupied strongly by the Philistines from at least 1158, according to archaeological data from Lachish, near Gath. Only an early reference to the cities of the coastal plain in Israel’s hands makes sense. Since all three of these cities were along the coastal strip and were stations along the international trade route, Judah was probably not able to hold them for any length of time. The Philistines, when they finally arrived on the scene, apparently fought the Egyptians for control of the area before ever running into Israel.

1:19–20. Judah could not drive out the Canaanites in the valley because they had iron reinforced chariots. This may seem to contradict v. 18, but apparently a partial success is in view. Caleb was given Hebron … as Moses had promised (cf. Jos 15:13).

1:21. The Jebusites living in Jerusalem are included among the Amorites in Jos 10, but they may have had a mixed ancestry. Ezk 16:3 suggests Jerusalem’s background was Canaanite, Amorite, and Hittite. The owner of the threshing floor David purchased later for the temple was Araunah the Jebusite. His name is probably the Hurrian word ewrine ("lord") and not a personal name at all.

3. Failure of the Northern Tribes (1:22–36)

1:22–25. The house of Joseph spied out Bethel. These spies were probably an "armed reconnaissance patrol," distinguishing it from the mission of the two undercover agents sent by Joshua to Rahab (Jos 2). The word spied is from the verb "to observe." The deliverance of the young man who betrayed the city is a simple parallel to the Rahab story. Kindly is chesed, the common word for God’s loyal, covenant-based love.

1:26. The man and his family who helped the Joseph tribes capture the city were allowed to escape to the north into the land of the Hittites, roughly equivalent to Syria today. The Hittites at that time controlled the region roughly north of the Litanni River, about 30 miles northwest of the Sea of Galilee.

1:27–36. This passage parallels Jos 13, adding detail but making no changes in the situation. Many of the tribes had difficulty driving the Canaanites out of their areas.

Manasseh included several key cities of the Jezreel Valley. Beth-shean controlled a strategic crossing of the Jordan River and remained in Canaanite and Egyptian hands. Later the Philistines took over the place and hung King Saul’s body from the wall (1Sm 31:2, 8–10).

4. Israel’s Lament (2:1–5)

2:1–5. Israel’s lack of an appropriate countermeasure for Canaanite iron chariots was not their biggest problem. Their lack of genuine commitment to the Lord resulted in Israel’s failure, and that set the stage for the era of the judges, a period of cyclical failure in the face of internal and external enemies. Since the Israelites did not obey the Lord by tearing down the altars of the Canaanites, they would become thorns in their sides and their gods would become a snare. Israel did not drive out the Canaanites, so their pagan culture continued to exist—and in some places to thrive—well into the Iron Age (beginning around 1200 BC). Likely, the Philistines of Iron Age I, rather than Israel, expelled the Canaanites.

B. The Theology of Sin and Grace (2:6–3:6)

This second prologue introduces the theological context of the period of the judges. Here is the account of another full generation that grew up knowing neither the Lord nor His doings. This unfortunate failure of the people over time to educate their own children contributed to many of the moral and spiritual breakdowns of Israel during this era.

The contrast between those who served the Lord (2:7) and those who served the Baals (2:11) is striking. The essence of godliness is a willingness to submit to the King, that is, the Lord of Israel, but the essence of sinfulness is a growing willingness to submit to the gods of the nations. Israel, surrounded by an ungodly culture, slowly took on the characteristic worldview of that culture and began to serve and worship the "Baals." The text here accounts for the distinction between the received religion of Canaan, found in the myths and legends represented in the Canaanite city of Ugarit, versus the folk religion of the region, which included individual Baals on every mountaintop and sacrifice place. Canaanite religious practice emphasized the fertility of land, animals, and man, through the imitative magic of prostitution and orgiastic feasting. This religious system was attractive to many Israelites.

The answer to the sin problem in Israel is not given all at once. In the progress of revelation, God chose at this time to reveal to Israel that sin is a corrosive problem that cannot be solved without His grace. Even the divinely empowered temporal solutions—the judges themselves—would not be the answer to the underlying sin problem. On the deepest level this is an object lesson about the need for Messiah, the great King.

1. Account of the Death of Joshua and the Aftermath (2:6–10)

2:6. The sons of Israel went each to his inheritance to possess the land. This is the ideal outcome of God’s instruction to the people to conquer the land. This passage follows chronologically from Jos 24:28.

2:7. In the phrase the people served the Lord, the word "serve" is `ewed, also used in v. 11 of the worship of the Baals. The point is not so much a syncretism as a contrast. That service, which should belong only to God, was given illicitly to the Baals. The elders … had seen all the great work of the Lord (lit., "the great doings of Yahweh"). The word "work" or "doings" normally refers to God’s miracles in the exodus and the conquest. These mighty acts of miraculous power were foundational to Israel’s history, but they stopped at the end of Joshua’s ministry. Not until hundreds of years later were the prophetic ministries of Elijah and Elisha authenticated with miracles. Other authenticating miracles occurred in the NT times, and then died out with the end of the apostolic era (Eph 2:20; Heb 2:3–4).

2:8–10. In the phrase another generation … who did not know the Lord, the word "know" (yada‘) implies a personal, experiential knowledge, not merely an intellectual acquaintance. That a generation could grow up without this vital relationship speaks volumes about the parents, and about the importance of the Dt 6 imperative to teach from personal passion.

2. Account of the Idolatry of Israel (2:11–13)

Next the narrator introduced the schematic called the "Judges cycles." Each of the cycles included the following elements in this approximate order: sin (the Jewish people fell into idolatry); subjugation (foreign powers vanquished and ruled Israel); supplication (the Jewish people cried out to the Lord); and salvation (God raised up judges to liberate Israel from foreign domination).

2:11. The term translated evil is hara‘ (lit., "the evil" or "the evil thing"). Ra’ is the common term for evil in the OT, and is almost always indefinite, emphasizing the abstract quality of evil. With the definite article, as here, the author specified a particular evil, namely, their serving the Baals.

Some scholars have suggested their evil was the sin of taking foreign wives. More likely, however, the often-repeated phrase Israel did evil in the sight of the Lord refers to Israel’s debauched practice of Canaanite religion, complete with its pervasive sensuality (see the comments under "B. The Theology of Sin and Grace [2:6–3:6]" above for information regarding Baal worship). The failure to drive the Canaanite population out of the promised land resulted in a cultural context for spreading depravity. The second generation of Israelites in the land had been effectively compromised.

The words the sons of Israel did evil occur in 2:11; 3:7, 12; 4:1; 6:1; 9:23; 10:6; and 13:1, each time at the introductions to the accounts of the major oppressions by foreign powers. The statement serves as a refrain, marking the progression of the evil in Israel.

Why is Baals in the plural, whereas the singular Baal occurs in v. 13? The myths of Baal, Yam, and Asherah speak of only one Baal. According to their beliefs, the great God El was an aloof and detached overlord who was said to be living far away on a mountain. Under him Baal was the god of fertility who made sure the rains came in season. His conflicts with the chaos monster, Yam ("the Sea"), and with Mot ("Death") form the core of Canaanite religion. With the prostitute goddesses Anat and Asherah, Baal was the model for Canaanite debauchery. In their theology, Baal engaged in sexual relations with these goddesses and thereby brought fertility to the earth. Their worshipers could generate their favor by also engaging in cultic sexual acts done in their name. Baal would then cause his worshipers’ crops and herds and procreative abilities to be fertile.

The plural "Baals" refers to various portrayals of Baal on hilltop shrines called bamot. Unfortunately, many of the Israelites simply adopted the seemingly attractive local religious traditions.

2:12–13. That Israel worshiped other gods refers again to the polytheistic nature of the Canaanite religion. Other peoples, including the Phoenicians, Moabites, Philistines, and others, worshiped a wide variety of gods and goddesses, most of whom fit the general fertility cult pattern. Yet many of them also had unique elements of evil or sensuality associated with them. Many stone and metal images of these gods have been found in the ruins of Canaanite and Israelite settlements.

3. God’s Anger Displayed in the Rise of Oppressors (2:14–15)

2:14–15. When God gave the people up to their plunderers, they were helpless to rise in their own defense. Wherever they went, the hand of the Lord was against them for evil. This contrasts strongly with God’s promise to Joshua in Jos 1:5: "No man will be able to stand before you all the days of your life." Had Israel lived in sincere obedience to God’s law, the Lord would have given them success. Their turmoil, however, was an indication of God’s judgment against them for their disobedience.

4. The Judges Raised Up as a Respite from Oppression (2:16–19)

2:16. Judges are introduced as deliverers raised up by the Lord. These judges stood in opposition to the oppressors, whom the Lord had raised up. God used oppressors and judges alike to teach Israel the principles of godliness.

2:17. Israel, however, failed to follow the Lord. The reason for their failure is made clear in this analysis: (1) They did not listen to their judges, that is, they refused to obey them. (2) They played the harlot and bowed … down to other gods. To "bow down" is to worship, in the sense of a wholehearted submission of life to a god. Here it is likened to spiritual unfaithfulness or harlotry. (3) They turned aside quickly from the way of their fathers who obeyed the Lord. (4) They did not do as their fathers had done.

2:18–19. The Lord had pity on the people because they were oppressed by their enemies. So he used judges to deliver them. But the success of any given deliverer was short-lived. The deliverance lasted until the death of the judge. Here is a powerful demonstration that deliverance available through even the greatest human leaders will always be deficient. A deliverer who could truly solve the deepest human problems must be infinite, not only in power, but even in being able to produce transformation in the lives of people. All others will eventually fall short.

5. God’s Anger at Covenant Transgression Resulted in Pagan Nations that Could Not Be Driven Out (2:20–23)

2:20–21. Israel had repeatedly transgressed God’s covenant, causing His anger to burn against them. Israel was not merely a people group sharing ancestors and culture. They were a nation explicitly chosen by God and created for His purposes. They were to exist in covenant relationship with Him forever—with the primary obligation to listen to and obey His voice.

2:22–23. God’s purpose in leaving the Canaanites and other nations was to test Israel. "Test" here, of course, does not mean that God was in doubt as to the outcome. It is clear that God, who knows the end from the beginning, knew that Israel would fail (Dt 31:29). The point was to demonstrate that fact through experience, and thus further demonstrate Israel’s need for a saving relationship with the Lord.

6. Nations Left to Test and to Punish (3:1–6)

3:1–2. That various nations were still in the land was a test for Israel. This meant that … generations of the sons of Israel would be taught war. But 2:22 states that God’s purpose in testing Israel was to see if they would obey Him (cf. 3:4). The ideal would have been universal godliness and obedience, as a result of which God would have established them peacefully and securely in the land. But the reality, because of sin, was growing ungodliness accompanied by intermittent wars. Every generation of Israel would experience threats and violence until the second coming of the Prince of Peace. The presence of Canaanite nations then fulfilled two purposes expressed here: to demonstrate, by failure, Israel’s need for the Messiah; and to chastise Israel for that failure by constant violence and warfare.

3:3. Some scholars question the reference to the five lords of the Philistines as if it were anachronistic. Of course there were Philistines in the land from as early as the time of Abraham who met with King Abimelech of Gerar, who was a Philistine (Gn 21–22). Possibly the Philistines were a relatively small people group along the coast, perhaps working as vassals of the Egyptians, until the large migrations began around the turn of the Iron Age (around 1200 BC). It is also possible, since the editing of Judges did not take place until the beginning of the monarchy (around 1000 BC), that this note about five Philistine kings was a name for the region from that era.

3:4–6. Again the nations in the land of Canaan were there to test Israel (cf. the comments at v. 1) to see if they would obey Him. Unfortunately the Israelites intermarried with the daughters of these unconquered nations and served their gods, thus failing the test.

II. Twelve Deliverers Demonstrate a Cycle of Increasing Failure (3:7–16:31)

The Early Judgeships:

Though 12 judges are often cited, there were actually only six major judges. Also, Shamgar was not, properly speaking, a judge. And Abimelech was a usurper and is not counted among the judges. Five minor judges appear by name only, without any account given regarding their oppressors or their wars, if any.

The first set of major judges, Othniel, Ehud, Deborah, and Gideon is presented in chaps. 3–10. They are generally sympathetic characters who served local constituencies and perhaps had overlapping terms of office. The moral tone of their stories is relatively high, but with a slow downward progression. The second set of judges includes only Jephthah and Samson (along with the five minor judges). The two are generally conceded to be late in the period (perhaps near 1100 BC), and to be overlapping in time, with Samson on the west of the Jordan and Jephthah on the east. There is little to admire in Jephthah and Samson. Jephthah may have sacrificed his daughter (Jdg 11:31 and 39), and he precipitated a deadly civil war (Jdg 12:1–6). Samson was an unmitigated scoundrel who killed many Philistines but ultimately failed to break their power over Israel.

The repeated statement that Israel did evil (2:11; 3:7, 12 [two times]; 4:1; 6:1; 10:6; 13:1) pointed out the need for a genuinely godly leader. In time, of course, even the kings themselves demonstrated their inability to maintain godly leadership.

A. Othniel: The Model of the Judges Cycle (3:7–11)

Othniel is given a brief discussion. His judgeship serves merely to demonstrate the pattern of the cycle.

1. Israel’s Sin of Idolatry (3:7)

3:7. Israel did what was evil (lit., "the evil thing"), explained by two statements: they forgot the Lord their God and they served the Baals and the Asheroth. The sin of transgressing the covenant began with forgetting the truth of the basic relationship. Israel had forgotten who they were and who the Lord was, and as a result they began to behave like the nations that surrounded them.

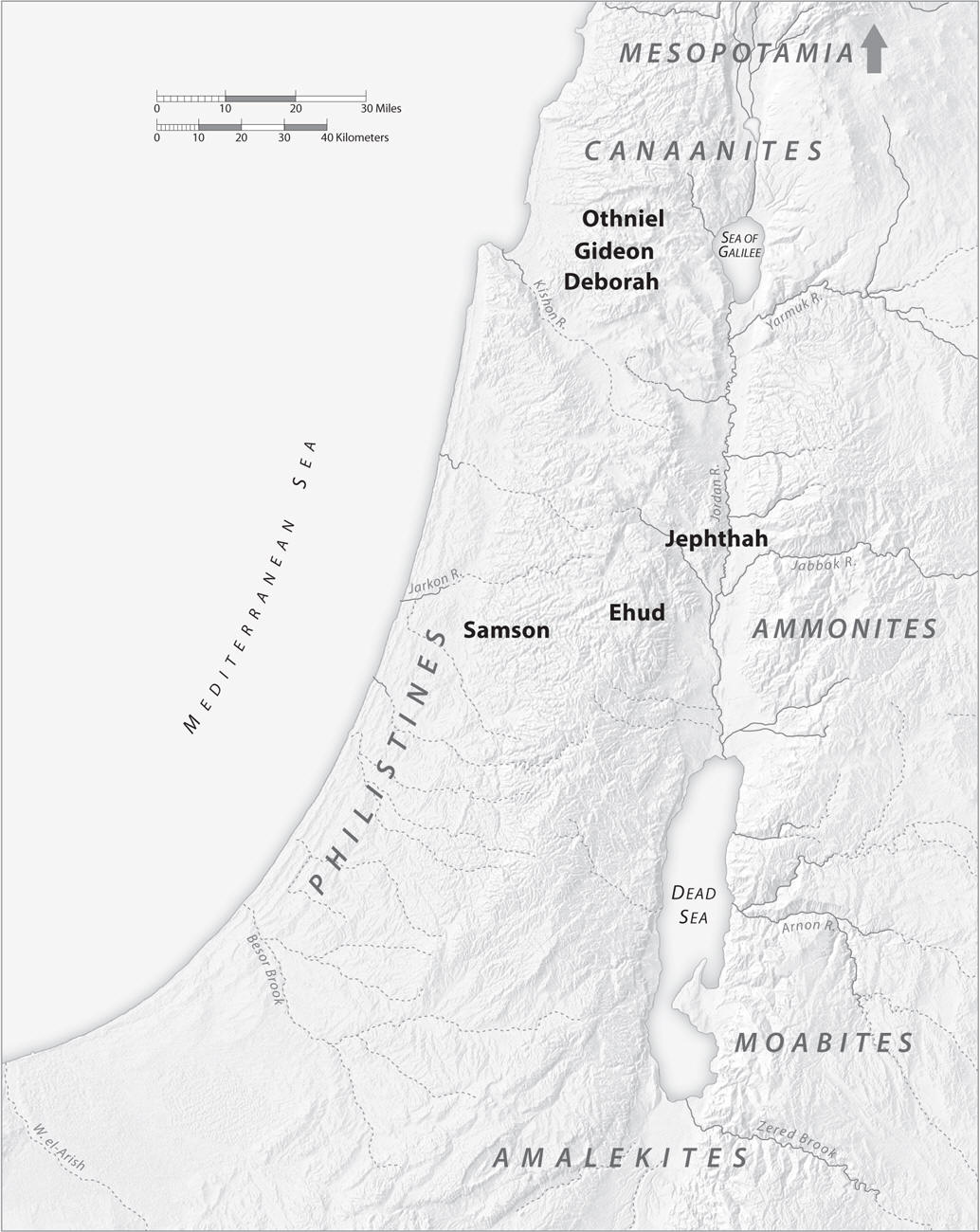

General Location of Major Judges and Adversaries

Adapted from The New Moody Atlas of the Bible. Copyright © 2009 The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago.

2. Israel Sold into Mesopotamian Oppression for Eight Years (3:8)

3:8. Subjection to a Mesopotamian power is the first of many such oppressions, and this is the only instance where the power was some distance away. All the later oppressors were close by. Little is known of Cushan-rishathaim ("Cushan of double evil," an epithet that may have been given him by the Israelites). The oppressor here is Mesopotamia (Hb. Aram-Nahariyim, lit., "Aram of the Two Rivers") referring more specifically to the Aramean or Syrian region at the northwestern corner of the Mesopotamian alluvial plain.

None of the history of the great powers of that time (Egypt, Mitanni, Hittites) is represented in this brief passage. Cushan must have been a warlord-sized king who was too small to be noticed by his major contemporaries.

3. Heartfelt Cry for Deliverance (3:9a)

3:9a. When Israel was truly contrite, the nation cried to the Lord. Then He raised up a deliverer. A deliverer (judge) was one who rescued a people whose situation was otherwise hopeless. The Bible is clear about the need of sinners for a Savior, not merely a coach or even a physician. People are not simply sick in sin, nor are they merely untrained in righteousness. Mankind is "dead in [their] trespasses and sins" (Eph 2:1) and in need of God’s grace for deliverance.

4. A Deliverer Raised Up: Othniel, Son of Kenaz (3:9b–10)

3:9b–10. Othniel, a brother of Caleb (Jos 15:13–19), and thus a younger contemporary of Joshua himself, prevailed over Cushan-rishathaim by the power of God. The fighting probably took place in the north, although Othniel was of the tribe of Judah.

5. Forty Years of Rest (3:11)

3:11. After noting the land’s 40 years of rest (perhaps the length of time is approximate), the passage ends with the note that Othniel … died. The rest from oppression lasted only for the life of this judge.

B. Ehud: The Left-Handed Judge (3:12–30)

Ehud was the next of the "major" judges—major in the sense that much detail is given of his work. Ehud was confronted apparently by a coalition of raiders led by the king of Moab, who set up his headquarters in the City of the Palms, that is, Jericho.

1. Eighteen Years under Eglon of Moab (3:12–14)

3:12. Moab was the desert kingdom directly east of the Dead Sea, from the Arnon River at the midpoint of the Dead Sea north to south, to the Zered River at the southern tip of the Dead Sea. During the Late Bronze Age, this area was sparsely populated. Archaeologist Nelson Gleuck found the ruins of approximately 22 towns or villages in this area dated to the time of this account.

3:13–14. Ammon was the kingdom on the plateau from the Arnon River to the Jabbok River, north of Moab, and the Amalekites were semi-nomadic peoples who inhabited much of the region. The city of the palm trees (Jericho) had been destroyed by Joshua and was in ruins at this time. Eglon must have built his summer palace in the fertile flat lands to the east of Jericho.

2. Ehud’s Clandestine Mission (3:15–24)

Ehud’s action here is what modern military leaders would call a "special operation." He went in under the false pretenses of diplomatic cover to carry out an assassination. Ehud planned his operation carefully, choosing a weapon and the setting for the greatest advantage. The cover, approach, execution, and retreat were all well planned, with the intention of summoning the tribes afterward. Ehud’s act is a finely detailed act of war. Significantly, that war had been imposed by Eglon, the invader and oppressor. So there is no inherent ethical problem in the Ehud cycle.

3:15. Ehud was left-handed. Through much of history and literature left-handed people have suffered bad press. Archaeology demonstrates that the left-handed were not considered a serious military threat. Figures on monuments in victorious military poses are almost always right-handed. For example, in the famous chariot scene from the chest of Egyptian King Tut, the king is drawing his arrow with the right hand. And on the Egyptian Narmer Palette King Narmer raises his mace with his right hand to smite an Asiatic prisoner. The gates leading into walled cities were approached by ramps that put right-handed soldiers at a disadvantage, with the shield arm on the wrong side. Various languages, in their handling of the vocabulary of left and right, put the lefty in a bad light. In Latin, for example, the right hand is "rectus" or "dextra," and left is "sinister."

This seemingly innate (and unreasonable) prejudice proved the undoing of evil King Eglon. He and his keepers simply could not believe that a left-handed man was a threat. This incident is particularly ironic in light of Ehud’s heritage; he was a Benjamite, lit., a "son of the right hand."

3:16. Ehud’s double-edged sword, hidden where it would not be found on the right hip, is an object of some interest. During the Late Bronze Age, most weapons were made of bronze, which was cast in a variety of heavy shapes. Bronze tended to be brittle, and thin blades were simply not durable enough for use. Most of the swords shown in the monuments of this period are the so-called "sickle" swords, shaped a bit like a sickle, with the single axe-like smiting edge on the outside. But Ehud’s sword must have been more like a dagger, with two sharp edges and small enough to be easily hidden in the folds of his garment. He made it himself, and it was about a cubit (18 inches) long, including the handle. Since it was probably made of bronze, it is unlikely it would have survived long in battle. It was a one-time-use weapon, specifically formed for this mission.

3:17–18. Warlords who could hold territory by force collected protection money (euphemistically called "tribute") from the villages in their area. No government services of any sort were provided for the people in such regions. Eglon certainly had no sense of empire. He was in business merely to extract money from his victims.

3:19. Whether Hebrew pesilim, from psl, "to hew or cut," is to be translated idols (NASB and most translations) or "stone quarries" (NIV), this place was clearly a well-known landmark near Gilgal. The Gilgal in question was probably not the better known Gilgal to the east of Jericho, but rather a town on the border of Benjamin and Judah north of the pass of Adummim, about 15 miles northeast of Jerusalem. From this landmark Ehud turned back and carried on his fatal conversation with the king.

3:20. Ehud went to Eglon while he was sitting alone in his cool roof chamber. In this upper room the rare breezes might be caught.

3:21–24. Ehud thrust his sword into Eglon’s belly. The stealthy treachery is emphatic, and is clearly portrayed as a heroic action. Ehud left the sword in the king’s stomach and fled. Relieving himself (v. 24) is literally "covering his feet" (cf. 1Sm 24:3).

3. Slow Response of Eglon’s Servants (3:25)

3:25. Ehud had locked the roof chamber when he left, so that Eglon’s men needed to use a key to enter. Keys in the ancient world were relatively unusual. Several examples have been found and are on display in the Israel Museum and elsewhere. Such keys were large items designed to reach through a door and interface with a heavy bolt on the far side.

4. Ehud’s Escape and the Muster of Ephraim (3:26–30a)

3:26–30a. Departing from Eglon, Ehud called for help by blowing a horn (shophar) to summon the tribe of Ephraim. Fighting men arrived quickly to block the fords of the Jordan, where ten thousand Moabites, all robust and valiant men were struck down (v. 29; cf. the comments on 1:4).

5. Eighty Years of Rest (3:30b)

3:30b. Eighty years takes the chronology down to the early to mid-thirteenth century, depending on the overlap with Othniel. This provides the earliest point in the chronology for Shamgar, who came after him (i.e., after Ehud).

C. Shamgar: An Enigmatic Interlude (3:31)

3:31. Some expositors call Shamgar a minor judge, but more likely he was not related to Israel at all, except that he was in the right place at the right time. Virtually every detail in this verse is a linguistic or archaeological problem.

Shamgar’s name is the first problem. It is not Hebrew. Various suggestions have been made. The Canaanite hypothesis is probably best, taking the name as a shin prefix participle on the Semitic verb mgr. Shin prefixes are unknown in Hebrew, but are found in Ugaritic and perhaps other NW Semitic languages, and they correlate to the Hebrew mem prefix found on some participles. Mgr is the common verb "to farm." That would yield the translation "farmer," which fits the oxgoad nicely.

Son of Anath may refer to his heritage from the village of Anath. Several such places have been identified. Or it may refer to a well-known Canaanite goddess of love and war. Perhaps Shamgar gained this label after his exploits recorded here.

At first thought the oxgoad may seem a strange weapon. The Hebrew is malamad, which is echoed in the name and shape of the Hebrew letter l (lamed). The oxgoad likely was a long stick with a point at one end for poking the ox and a shovel at the other for doing necessary work around the ox. Sharpening either or both ends would produce a formidable weapon in the hands of a stout peasant warrior.

Shamgar’s Philistines are a problem because of their timing. Rameses III defeated the great wave of Sea Peoples around 1190 BC. Israeli archaeologist David Ussishkin (who led the excavation at Lachish in the Judean Shephelah) insists that the Canaanite cities of the plain did not fall until roughly 30 years after that time (cf. New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land [Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society], 904, and other references in the literature). Shamgar’s timing is difficult to pin down. He is said to have done his work after Ehud. He is also said to have been a contemporary of Jael and Deborah (5:6), putting him in the late thirteenth century. As stated earlier, the Philistines may refer to a regiment-sized force of Philistines that raided the coast of Canaan some 50 years before their great migration.

The closing note in this verse announces that Shamgar also saved Israel. The Hebrew yasha’ is the same term used of deliverance by the other judges, and so this has led some to classify Shamgar as a judge.

D. Deborah: A Mother in Israel (4:1–5:31)

Deborah, the third of the judges, and the only woman in the sequence, appeared about the same time as Shamgar, mentioned in 5:6. Her gender, the ineffectiveness of Barak, and even her husband Lappidoth (4:4) contribute to the feeling that strong male leadership was lacking at that time in Israel.

1. The Military Campaign against Hazor (4:1–24)

This chapter recounts a second battle of Hazor (following Joshua’s initial burning of the site in Jos 11). This cannot be a duplicate report, for the details are different, except for the name of the king.

a. Twenty Years under Jabin of Hazor (4:1–3)

4:1–2. Joshua 11 also records the fall of Hazor, which Joshua burned. Its king at that time was also called Jabin. The Canaanite population seems to have continued until the beginning of Iron Age I (c. 1200 BC). Jabin may have been the king’s name, or it may have been his title, in much the same way the terms Pharaoh, Czar, Caesar, and others are used as titles.

4:3. Sisera, Jabins’ commander, had nine hundred iron chariots. This is a huge chariot army, but not unparalleled in the ancient world. The Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III spoke of capturing over 900 chariots at Megiddo (c. 1470 BC). A chariot army required substantial state resources. One could compare the development and deployment of a chariot army to the building of a modern aircraft-carrier battle group. The same resource commitment, technology research and development, personnel training and support, and logistic infrastructure went into fielding such an army. Chariot soldiers could not be militia or conscripts, but had to have been professionals who devoted their full time to training and preparations. In the feudal structure of Canaan these men would have been land-owning nobility with servants to care for their properties.

Chariot horses were specially bred and trained for combat. Most horses will not voluntarily proceed into the kinds of situations pictured on monuments. They must be trained to charge, trample, and obey commands under noisy, frightening circumstances. Such horses would have been quite expensive and would have required large pastureland and training areas.

Hazor’s lower city, nearly a square mile in area, was once believed to consist mostly of the Canaanite chariot camp. However, Israeli archaeologist Yagael Yadin’s excavations have shown the lower city to have been a relatively densely populated area during the Late Bronze Age (NEAEHL, 597). The horses and chariots may have been housed in the surrounding countryside. Certainly the professional troops for such an army could not have all lived in Hazor.

b. Deborah the Prophetess Called on Barak the Soldier (4:4–10)

4:4–5. Deborah, who was judging Israel at that time, may have been a "seer"-type prophet, whose visions under the palm tree provided inspiration for the people. The culture of the era would not normally have supported a woman in military and political leadership, so the situation speaks of the probable lack of qualified men. She is an "exception that proves the rule"—that is, the rule being God’s intention that men provide spiritual leadership (Gn 2:20, 23; 1Tm 2:11–15). The extraordinary circumstances around her serving as a judge in Israel indicate just how unusual it was for a woman to exercise this kind of leadership. Deborah’s palm tree must have been a well-known landmark, but of course it is impossible to identify it today. Palm trees of various kinds are common throughout Israel.

4:6–10. Deborah’s involvement with leaders from Naphtali and Zebulun (v. 6) indicates the national scope of the Canaanite problem at this point. Barak’s home was Kedesh of Naphtali, overlooking the Hula Valley in the Lebanon range, about 16 miles north of the north end of the Sea of Galilee. The Kedesh in vv. 9–10, which was used as a meeting place, cannot reasonably be the same place. This Kedesh is probably near the south end of the Sea of Galilee and the slopes of Mount Tabor. From the northern slopes of Tabor one could see ten thousand men gathered for battle, but they would be hidden from the Canaanite forces in Jezreel to the south.

c. Heber the Kenite Introduced (4:11)

4:11. Heber the Kenite is introduced here in anticipation of the exploit of Jael, his wife (v. 17). The oak in Zaanannim is probably near the lower Galilee Kedesh and was mentioned in Jos 19:33 as a landmark on the border of Naphtali.

d. The Battle of the Kishon (4:12–16)

The climax of this confrontation took place on ground apparently of Deborah’s choosing, since no self-respecting chariot captain would willingly deploy his chariots in a swamp.

4:12–13. Mount Tabor is the volcanic dome that dominates the central Jezreel Valley and is the primary landmark along the international trade route in this region. The gathering of a major force at Mount Tabor had obvious military significance to those who needed to keep the trade route open. Sisera deployed his forces—some nine hundred iron chariots and the foot soldiers with them—from Harosheth-hagoyim (perhaps in the western Jezreel Valley area) to the river Kishon, a swampy area near Megiddo that drains through the pass of Beth Shearim into Haifa Bay. This location would have seemed preferable since it was quite broad, with room to deploy chariots and associated infantry. An observer from a high spot near Nazareth would think this land was ideal for fighting, when in fact it can turn into a quagmire in the rain.

4:14–16. Barak defeated Sisera, killing every soldier in his army.

e. Sisera Meets Jael (4:17–22)

4:17–22. In a serious breach of hospitality, Jael the wife of Heber the Kenite killed Sisera by pounding a tent peg through his head into the floor while he slept. Barak found him there, killed by a woman. The irony of Jael’s deadly action, in the larger context of Deborah’s leadership, points to a failure of the classic biblical pattern of male leadership. As Adam was first created, and then Eve, the Bible shows ontological male-female equality (Gn 1:27) with a pattern of male functional leadership (Gn 2:20, 23; 1Tm 2:11–15). Hence, the actions of Deborah and Jael provide the exception that proves the rule—that men are expected by God to be godly leaders. Moreover, it emphasizes the sorry state of Israel’s male leadership in the period of the Judges, being so problematic that women were required to lead in this military situation.

f. The Long Campaign against Jabin (4:23–24)

4:23–24. Apparently the struggle against Jabin did not end on the day of the battle of the Kishon. Instead Jabin was not destroyed until some time later. The text does not suggest that Hazor was burned or even occupied.

2. The Song of Deborah (5:1–31)

This song, one of the earliest Hebrew songs, bears most of the earmarks of Hebrew poetry, including the parallelism and meter. This chapter provides a number of insights into the life of Israel in the settlement period.

a. Call to Praise the Lord (5:1–5)

5:1–2. The words the leaders led in Israel are parallel to the words the people volunteered. The enigmatic term pera (leaders, NASB) must be translated as something to do with leadership—in contrast to the people who volunteered. Ugaritic suggests a leadership function.

5:3–5. The song challenges kings to hear and rulers to give ear. Sing (shir) and sing praise (zāmar) are technical terms also found in the Psalms (e.g., 49:1, "hear," "give ear"; 30:4, 12, "sing"—the participle mizmor is generally translated "psalm"). The attitude toward the kings of the earth establishes an anticipatory pattern: that is, the author is looking forward to the day when the nations and their kings will bow and worship the King of kings (Ps 2:8; 110:1).

b. Deborah’s Motivation, as a Mother in Israel (5:6–11)

5:6–7. In the days of Shamgar and Jael, the highways were deserted. The instability of life in Israel at the end of the Late Bronze Age is poignantly illustrated in this passage. The roads could not be protected and made secure because there was no longer any central government to do the job. For most of the Late Bronze II era (c. 1400–1200 BC) the Egyptians had given up on their pretensions to empire. Israel was certainly not a central power in any sense of the word, and had little overall influence on the situation. Village life consisted of the families who lived on the land, namely, subsistence farmers and stockkeepers who provided food for marketplaces in larger cities. A secure village life was essential for the stability of the overall economy.

The last major Asiatic campaign of the Egyptian Empire was the expedition of Pharaoh Mernepthah (c. 1230 BC), recorded in the famous Israel stele (which celebrates Mernepthah’s victory over the Libyans). Deborah’s description of life in Israel at the end of the Late Bronze Age is a good explanation for the need Mernepthah found to make his expedition in the first place.

5:8–9. Archaeologists have long held that no walls datable to the Late Bronze Age existed in the land of Israel, and so they question the statement in v. 8 that war was in the gates. However, even a cursory examination of the Egyptian monuments dating to that period show the major cities of Israel/Canaan, secure behind their massive walls, falling to the armed technology of Pharaoh. Many of these walls certainly were built in the Middle Bronze Age, and many of them continue to stand today! There is no reason that the walls, even in time of peace and expansion, could not have continued to serve their intended purpose during the Late Bronze Age.

Deborah clearly had in mind here (and in v. 11) the gates of the regional commercial cities. When trade and agriculture are disrupted by bandits, a nation is in deplorable condition. These cities, like the Canaanite centers, were fortified, at least in a rudimentary way, especially as chaos again swept over the land.

In v. 8 the Hebrew word for Then is ‘az, a common temporal particle used to introduce the military moves mentioned in vv. 8b, 11b, 13a, 19, and 22. Both commanders and volunteers (v. 9) responded in times of warfare.

5:10–11. The mention of the sound of those who … recount the righteous deeds of the Lord may provide a glimpse into Israel’s most important communication device: word of mouth. Much of the history and lore of Israel was committed to poetry and song for dissemination to the whole culture. The rich (those who ride on white donkeys and sit on rich carpets) and travelers were challenged to sing of the Lord’s victory.

c. The Muster of the Tribes (5:12–18)

5:12–13. The nobles and the warriors were those who came to Deborah for help in the midst of the trouble with the northern Canaanites. The word "nobles" is the Hebrew ‘adirim, from ‘adar, "to be prominent or powerful," and "warriors" translates the more common word gibborim, used of men of substance who were also prepared to go to war. David’s "mighty men" are called gibborim in 2Sm 23:8–39. Boaz, the husband of Ruth, is called a gibbor, referring to his substantial place in the community.

The Hebrew word translated survivors (Jdg 5:13) is sarid. But a surviving remnant (as from a defeat) seems out of place here. N. Na’aman has suggested that this Hebrew word refers to the town of Sarid (c. six miles south of Taanach, about 25 miles southwest of the Sea of Galilee, and a likely mustering spot for the Canaanites, see VT 40 [1990]: 423–26). That would yield the translation, "Then down to Sarid he marched to the nobles; the people of the Lord came down to me as warriors." This is the preferred view, since it smoothes the interpretation.

5:14–18. Verses 14–18 give the poetic account of Deborah and Barak’s summons to battle. Ephraim and Benjamin, two southern tribes, are mentioned first, perhaps because of their association with Deborah. Why Ephraim is associated with Amalek is difficult to know, but perhaps it is because some of Ephraim’s territory lay in formerly Amalekite lands. The staff of office refers to a "commander’s staff," held by leaders of military units. The staff may have been a ceremonial emblem or a practical weapon. The commander would be called on to dispatch the leaders of a defeated enemy, and might do that with the mace or axe he carried for that purpose. In some contexts this staff seems to be the tool of a scribe, so some have suggested that this staff was an administrator’s emblem; but that seems unlikely here in the midst of battle.

Machir usually refers to the half tribe of Manasseh that stayed east of the Jordan in the Golan, the far north region of Israel. But here it refers to Manasseh itself, since the fighting took place on Manasseh’s western territory in the Jezreel Valley. Zebulun and Naphtali (v. 18) are singled out for special praise, presumably because they were the first to respond to the call to duty. Their unique position across the international trade route made them a difficult and urgent problem for the Canaanites.

Other tribes, farther removed from the trouble, did not participate, and are mentioned in anger. Reuben, on the border with Moab, was the farthest away, and chose to stay in relative tranquility beside the campfires, listening to the whistling or playing small flute-like instruments to call the flocks of sheep. For Gad, Deborah uses instead the name Gilead, usually the pastoral region north and east of the Dead Sea between the Yarmuk and the Jabbok rivers shared by Gad and Manasseh. Gad was probably in mind here to round out the Transjordan tribes.

The mention of Dan who chose to stay in ships indicates that Dan was not engaged in the battle because they were occupied with Canaanites and Philistines to the west. This verse probably dates to a time before Dan had migrated to Laish in the far north. The reference to ships implies that Dan occupied at least some of the Mediterranean seacoast. The river Yarkon, on the northern border (now in the northern suburbs of Tel Aviv), would have provided an anchorage for small vessels, as would the promontory at Joppa.

Asher was overrun with Phoenicians by this time. Most of the coastline, from Carmel to Tyre, seems to have stayed in Canaanite and Phoenician hands. There is little evidence of early Israelite occupation here until the time of Solomon.

d. The Battle at the Kishon (5:19–23)

5:19–22. The battle took place at Taanach near the waters of Megiddo. Taanach is Tel Ta’anak on the southern edge of the Jezreel Valley, about 25 miles southwest of the Sea of Galilee. The Kishon River runs through the swampy lowlands to the north of the city. The reference to the fighting stars is probably part of Deborah’s poetic license. Most likely she was referring to the sudden downpour of rain from the heavens, which God sent just in time to defeat the Canaanite chariots. Nothing impedes a chariot maneuver like too much soft ground. The dashing of his valiant steeds is almost certainly sarcasm, for the horses were up to their haunches in mud.

5:23. Deborah pronounced a curse on Meroz, a village whose location is not known but was probably in the vicinity of Mount Tabor and the battlefield, apparently because its inhabitants did not come to the Israelites’ aid in the battle or in apprehending Sisera when he fled.

e. Jael: Most Blessed of Women (5:24–27)

5:24–27. This extended account of Jael’s heroic act spells out in poetic style what was recorded in prosaic style in 4:17–21.

f. Lament of Sisera’s Mother (5:28–31a)

5:28–31a. This poetic description of Sisera’s mother is not a statement of sympathy for her but rather is a sardonic evaluation of her false expectations. She anticipated that Sisera should have already returned in victory and wondered at his delay in coming. Her princesses incorrectly encouraged her to believe that Sisera and his warriors were delayed by dividing the spoil, ravaging two maidens for every warrior, and gathering spoils of expensive dyed work of double embroidery (likely to be received by her). The writer implies she would experience great sorrow and disappointment when discovering the truth of Sisera’s end and is mocking all such arrogance toward the Lord. She calls on the Lord, therefore, asking that all [His] enemies perish in the way of Sisera and that those who love the Lord grow stronger like the rising of the sun in its might.

3. Forty Years of Rest (5:31b)

5:31b. This note takes the chronology to about 1200 BC, or the end of the Late Bronze Age II in Canaan.

E. Gideon: A Lesser Son of a Lesser Son (6:1–9:57)

The Gideon cycle represents the largest portion of the book of Judges. It has 100 verses. Compared with the Samson episode, which has 71 verses, Gideon’s victory was of major importance to the entire nation, since the Midianites and their allies raided wherever they pleased throughout the land. Chapter 9 should probably be included in the cycle, since it recounts the misadventures of Gideon’s son, Abimelech.

Gideon appeared on the scene as an unlikely deliverer. While he was a relatively godly man, he was immature and timid. Many scholars have tried to demonstrate the steady decline of Israelite morals and leadership in a downward spiral. It is better to see the first set of judges, which ends with Gideon’s story, as good but incomplete heroes. But lasting deliverance was yet to come.

1. Introduction to the Gideon Episode (6:1–10)

This portion introduces the Midianites and their allies, along with the hero of the story, Gideon. The story is set in the north, in the Jezreel Valley of Manasseh, near Gideon’s town of Ophrah. This town should probably be identified with ruins found in the modern town of Afula, conveniently near Mount Moreh, the Jezreel Valley, and En Harod (all about 15 miles south of the Sea of Galilee), sites that figure in the narrative.

a. Seven Years of Oppression by Midian (6:1–6)

6:1–6. The Midianites were the offspring of Abraham, through his handmaid Keturah (Gn 25:2). They were camel caravaneers in the Joseph narrative (Gn 37), close allies and relatives of Moses in the wilderness (Ex 2:15–25), and objects of an Israelite attack and plundering (Nm 31:1–24). The Midianites were probably a broad collection of related tribes, led by separate "kings" or "princes," without a common political focus. The transportation for Midianite aggression was the camel, which gave them both range and speed, allowing the raiders to do their damage and get away before effective counterforce could be mounted. The Midianites with the Amalekites and the sons of the east destroyed Israel’s troops, attacking like locusts in number. The Amalekites, descendants of Esau (Gn 36:12) had been enemies of Israel before (in Nm 14:45 and afterward). The sons of the east (bene qedem) are nomadic peoples in general, perhaps other descendants of Esau not otherwise specified.

b. The Covenant Message of a Prophet (6:7–10)

6:7–10. The sending of a prophet was a new development. Previously the people had cried out and had been rewarded with deliverance by the Lord in the form of a judge. This time a prophet, otherwise unknown, was sent to encourage them not to fear the gods of the Amorites and to deliver the rebuke, you have not obeyed Me.

2. Gideon’s Call to Deliver Israel (6:11–40)

This extended account of Gideon’s call to the work puts him in a different class from other judges, who simply appeared on the scene or were given brief histories. Gideon was not a nobleman, even though his father Joash was apparently the headman of the district. His family is of little importance outside the region. That seems to be the point of the passage, as God demonstrated His willingness to work through the most humble and the most poorly equipped if they will walk in faith. Gideon’s growth in faith and courage is a theme in this passage.

a. Gideon Called by the Angel of the Lord (6:11–18)

6:11. The angel of the Lord spoke to Gideon when he was beating out wheat in a wine press. Wheat was normally threshed on a wide, flat beaten area called a threshing floor. The best ones were on high ground in the midst of the fields. The idea was to dislodge the grain from the stalks by marching oxen and people over them. Next came winnowing, tossing wheat and chaff in the air to allow the wheat, which is heavier than the stalks and chaff, to fall to the threshing floor while wind blew away its chaff. This process was normally a time of communal celebration and was easily visible to anyone passing by. But the Midianite threat made any such event impossible. The wine press, on the other hand, was a square or round vessel, often cut out of the rock, in which grapes could be trodden. The juice from this process ran through a conduit to a lower and smaller wine vat from which the juice was collected in jars for fermentation. Such presses are normally found in the midst of gardens and vineyards, out of sight of passersby. Gideon was so fearful of the Midianites that he prepared this grain in a secluded wine press. He no doubt hoped to be able to thresh enough grain for a meal or two. This speaks of the desperation of the people under the oppression of the Midianite raiders.

6:12–14. The angel of the Lord appeared to him at the wine press. Scholars continue to argue about the identity of the angel of the Lord in this passage and throughout the OT. Since this angel has the authority of God Himself and was actually willing to accept worship, it seems likely that this is a theophany, a visible manifestation of God on earth. This is the extent that the text reveals. Nevertheless, since the Scriptures affirm that "No one has seen God at any time" and it is "the only begotten God … [who] has explained Him" (Jn 1:18), this visible manifestation was likely a preincarnate appearance of Christ (or a Christophany). When Gideon questioned why the Midianites oppressed Israel, the angel told him that Gideon was being sent by God to deliver Israel.

6:15. How shall I deliver Israel? Gideon’s humility is not feigned. He was really an insignificant son in an unimportant family. In a society in which clan pecking order was paramount (cf. the dispute with Ephraim later) Gideon was simply being realistic about his chances of gaining a following.

6:16–18. God’s answer to Gideon, Surely I will be with you, is reminiscent of God’s call of Moses. In answer to Moses’ complaint, "Who am I?" God replied, "I AM" the One who is sending you to Pharaoh (Ex 3:14). The point is clear: a person’s social status is insignificant when compared to walking with God. The power and the strength are in God Himself.

b. Gideon’s Presentation and Fear (6:19–24)

6:19–24. The presentation of an offering to the angel of God demonstrates Gideon’s understanding that he was in the presence of God. The offering was accepted by the angel in the classic way—by a consuming fire. In the early biblical period all sacrifices were accepted by fire that issued from the presence of God (Lv 10:1–2; 1Kg 18:38).

Gideon’s fear in the presence of the angel is only reasonable if this was a divine manifestation. The angel’s reassurance was a means of building Gideon’s faith.

The altar Gideon built was another step of faith. The statement about the altar’s continued existence (To this day it is still in Ophrah of the Abiezrites) indicates that the book was either written or had a final editing a significant time after the events described.

c. Hacking the Altar and Asherah (6:25–27)

6:25–27. Following Gideon’s call by the angel of the Lord, he was commanded to demonstrate (and stretch) his faith by destroying his father’s altar to Baal and the Asherah pole nearby. The altar was a structure of cut stones where sacrifices were made to Baal. The Asherah pole was a sacred tree or carved pole set in the ground representing the Asherah consort of Baal. Together the two elements formed the Canaanite high place, scene of the debauched worship of the Baal cult, often involving immoral acts by the worshipers in order to curry the favor from Baal to grant fertility to one’s endeavors. This format was adopted by Israelites, and was opposed only by the godliest of the kings of Judah.

Gideon’s destruction of the high place was a severe blow to his entire community. Much as a synagogue, church, or mosque would be to later towns, the high place was a focus of the investment of resources, both financial and emotional. Its destruction made a clear statement.

d. Confrontation with Joash (6:28–32)

6:28–30. The destruction of the altar of Baal and the Asherah pole was a blow to the entire structure of that community. A death sentence for Gideon seems outlandish to modern ears, but would have made perfect sense in the ancient world. When the men of the city learned that Gideon was responsible, they wanted to kill him.

6:31–32. But Joash, Gideon’s father, said, let him [Baal] contend for himself. This statement was a challenge to the worldview of the people of Ophrah. If Baal were who he claimed to be, he could certainly take care of himself. In fact baalism focused on the ability of Baal to defeat the chaos monster and even death itself, bringing order and life to the people of the world. If any of this were actually true, it would be no small matter for Baal to destroy Gideon on the spot. But when this did not happen—and no doubt many there must have expected such a reaction from Baal—this was a powerful testimony to the helplessness of the Canaanite god. This statement by Gideon’s father is witness to the underlying but dormant faith in the God of reality that continued to smolder in the hearts of Israel.

e. Muster of the Northern Tribes (6:33–35)

6:33–35. The eastern peoples again came across the Jordan and camped in Jezreel. So the Spirit of the Lord came upon Gideon; and he blew a trumpet. The words "came upon" translate the Hebrew labash, "to clothe," or "to put on clothing." This is a more picturesque image than the simple statement in 3:10 that the Spirit of the Lord "came upon" Othniel.

f. Sign of the Fleece (6:36–40)