NEHEMIAH

Bryan O’Neal

INTRODUCTION

The book of Nehemiah contains narratives that deal with the last events of the Hebrew Scriptures, recounting the circumstances of the third wave of Jewish people returning from the Babylonian exile in 444 BC, the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem, and the rededication of the temple and people to godliness. The book begins in the Persian city of Susa, with Nehemiah hearing of the ongoing disrepair of the walls and gates of Jerusalem, which leads to his request to King Artaxerxes that he be allowed to lead a return to Jerusalem to see to the reconstruction of the city. That request being granted, the book then details Nehemiah’s successful work as governor in rebuilding the walls, the opposition that the people faced, and the spiritual renewal that followed that successful labor. The book concludes with an account of Nehemiah’s final efforts to sustain that commitment to spiritual faithfulness. The close of the book includes information that marks the conclusion of the biblical history of the OT, though 2 Chronicles serves as the last book in the Hebrew canon. Nehemiah has the records of the last actions of the OT, marking the beginning of the silence of divine revelation lasting until the first events opening the NT, namely Luke’s record of the angel Gabriel appearing to Zacharias in Lk 1.

Author. In the Hebrew Bible the books of Ezra and Nehemiah are treated as a single book ("Ezra-Nehemiah"), spanning nearly a century of history. The latter part, separated as a distinct book in the English Bible ("Nehemiah"), contains the "Nehemiah memoirs" which purport to be the first-person writings of Nehemiah, the two-term governor of Judea in the fifth century BC. Some of the material contained in the book (particularly most of chap. 7, which is a near-exact repetition of the earlier writing of Ezr 2) is obviously drawn from other sources, which the author/editor chose to include in the text. This commentary adopts the traditional view that Nehemiah is the author/editor of the book bearing his name.

Date. The events recounted in Nehemiah range from the report of the disrepair of Jerusalem coming to Nehemiah in 445 BC, through his first term as governor of Judea (a period of approximately twelve years), followed by a period of undetermined length during which Nehemiah was presumably back in Persia, and a brief account (chap. 13) of several corrective actions Nehemiah takes in an apparent second term as governor. All told, the events of the book span approximately 15–20 years, bringing its events to a close about 425 BC and the book in its final form before the end of the fifth century BC.

Recipients. Nehemiah wrote his book to the faithful remnant of post-exilic Israel to show them God’s gracious restoration of the Jewish people from captivity. By revealing God’s blessing in recapitulating the conquest as in the days of Joshua, he also looks forward to the ultimate blessing of restoration at the end of days (see comments at the end of chap. 13).

Purpose and Theme. One obvious purpose of the book of Nehemiah is to chronicle the history of the Jewish people during the period of the return from exile to see them reestablished in the land of promise and awaiting the coming of Messiah. Too often the book is seen as mere history, or as a leadership manual using Nehemiah for a character study. Additionally, prayer is a common theme in Nehemiah as the narrator prays several times (1:5–11; 2:4; 4:9) and regularly brackets a section of the text with "Remember me, O my God" or "Remember them" (5:19; 6:14; 13:14, 22, 29, 31).

Yet, the book is primarily a recapitulation of the initial conquest of the land of Canaan under Joshua, as will be detailed throughout the commentary. This understanding of Nehemiah as a "second Joshua" parallels the common portrait of Ezra as a "second Moses," one who restores the law to the people. Just as Moses brought the law to the people but it was left to Joshua to bring the people into the land, so Nehemiah completes that which Ezra initiates. Much textual evidence supports this interpretation, including: (1) Nehemiah’s opening appeal to Dt 20:2–4 (Neh 1:8–9); (2) Nehemiah’s secret scouting of Jerusalem’s walls in 2:13–15 (compare the spies’ visit to Jericho in Jos 13:16); (3) the division of the labor of the walls in Neh 3 paralleling the division of the conquest of the land in Jos 13–19 (note Nehemiah’s explicit but rare usage of "portion" in Neh 2:20, and "inheritance," in 11:20; for the use of "portion" in Joshua, see Jos 14:4; 15:13; 17:14; 19:9; 22:25; for some of the uses of "inheritance," see Jos 11:23; 13:6–8, 14–15, 23–24, 28–29, 32–33); (4) the restoration of the Feast of Booths, explicitly reminiscent of similar celebrations in the time of Joshua (Neh 8:17), and culminating in the dedication of the walls as the Jewish people marched around the city led by trumpet-blowing priests (Neh 12). This march clearly echoes a similar procession initiating the prior conquest under Joshua with the defeat of Jericho (Jos 6). For these reasons, the central theme of the book of Nehemiah is "the reconquest of Canaan."

Contribution. Nehemiah completes the historical record of God’s great narrative of His work with the Jewish people in the OT—from the call of Abraham and the exodus from Egypt, through the initial conquest and the reigns of the kings, to the Babylonian exile and the return of the Jewish people to the promised land. As the book concludes, Israel is a purified people, restored to the land of promise, worshiping in a rebuilt temple—all things necessary and in preparation for the coming of Messiah.

Background. Nehemiah is about events during the end of the Babylonian exile, during the period when, under the Persians who conquered the Babylonians, the Jewish people were allowed to return to the land of Israel. The northern kingdom of Israel, comprised primarily of ten Jewish tribes, had been defeated and scattered by the Assyrian conquest in 721 BC. The southern kingdom of Judah, made up primarily of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin with substantial numbers of Levites, endured until the Babylonian conquest under Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BC. Nebuchadnezzar took captive much of the population of Jerusalem, including the noble and royal families, deporting them to Babylon. With the later fall of the Babylonian empire to that of the Medes and Persians (beginning in 539 BC), the Jewish people were eventually allowed to begin returning to their homeland after the 70 years of exile prophesied by Jeremiah (Jr 29:10). The first return under Zerubbabel (a descendant of David) occurred in 538 BC, followed by a later return led by Ezra the priestly scribe in 458 BC. Thus, some of these Jewish people had been back in the land for over 90 years as the book of Nehemiah opens (445 BC), explaining his surprise and lament that the walls and gates of Jerusalem remained in shambles, and prompting Nehemiah’s request of Artaxerxes that he might lead an expedition to restore Jerusalem. In the absence of a strong political presence in Judea, local power devolved to several petty nobles, among them Sanballat the Horonite, Tobiah the Ammonite, and Geshem the Arab (the descendants of many of Israel’s ancient enemies); these figures became Nehemiah’s nemeses in his work of reconstruction and restoration.

OUTLINE

I. The Plight of Jerusalem and the Jewish People (1:1–2:20)

A. Nehemiah Is in Babylon and Hears of Jerusalem’s Plight (1:1–2:8)

1. Jerusalem’s Plight (1:1–3)

2. Nehemiah’s Prayer (1:4–11)

3. Artaxerxes’ Permission (2:1–8)

B. Nehemiah Travels to Jerusalem and Surveys the Situation (2:9–20)

1. Travel to Jerusalem (2:9–10)

2. Surveying the Walls of Jerusalem (2:11–16)

3. Beginning the Work of Rebuilding (2:17–20)

II. The Rebuilding of the Walls (3:1–6:19)

A. Nehemiah Leads the Rebuilding of the Walls (3:1–32)

B. Opposition: the Military Challenge (4:1–23)

1. The Mockery of the Opposition (4:1–6)

2. The Threat of Violence (4:7–15)

3. The Renewed Work (4:16–23)

C. Opposition: The Moral Challenge (5:1–19)

1. The Problem of Usury (5:1–13)

a. The People’s Complaint (5:1–5)

b. Nehemiah’s Response (5:6–13)

2. The Example of Nehemiah (5:14–19)

D. Finishing the Wall (6:1–19)

1. The Physical Threat (6:1–9)

2. The Political Threat (6:10–14)

3. The Wall Complete (6:15–19)

III. The Rebuilding of the People (7:1–10:39)

A. Genealogies (7:1–73)

1. The Instructions for Security (7:1–4)

2. The Genealogical Record (7:5–65)

a. The Returned Exiles with Genealogical Records (7:5–60)

b. The Returned Exiles without Genealogical Records (7:61–65)

3. Summary (7:66–73)

B. The Public Reading of the Law (8:1–18)

1. The Reading of the Law (8:1–8)

2. The Sacred Feast (8:9–12)

3. The Feast of Booths (8:13–18)

C. The Confession and History of Israel (9:1–37)

1. The Assembly of the Levites and People (9:1–5)

2. Creation and the Call of Abraham (9:6–8)

3. The Exodus and Wandering (9:9–22)

4. The Conquest under Joshua and Subsequent Unfaithfulness (9:23–31)

5. Confession and Repentance (9:32–37)

D. The Establishing of a New Sacred Covenant (9:38–10:39)

1. The Signers of the Covenant (9:38–10:27)

2. The Content of the Covenant (10:28–39)

IV. The Dedication of the People, Walls, and Temple (11:1–13:31)

A. Populating Jerusalem and Its Region (11:1–36)

B. Dedicating the Walls of Jerusalem (12:1–47)

1. The Priests and Levites Who Returned from Exile (12:1–21)

2. The Leading Levites (12:22–26)

3. Purification of Levites, People, and Wall (12:27–30)

4. Two Choirs (12:31–43)

a. First Choir under Ezra (12:31–37)

b. Second Choir under Nehemiah (12:38–43)

5. Worship and Celebration (12:44–47)

C. Purifying the Promised Land (13:1–31)

1. Purifying the Temple (13:1–14)

2. Purifying the Sabbath (13:15–22)

3. Purifying the People (13:23–29)

4. Purifying the Priests (13:30–31)

COMMENTARY ON NEHEMIAH

I. The Plight of Jerusalem and the Jewish People (1:1–2:20)

A. Nehemiah Is in Babylon and Hears of Jerusalem’s Plight (1:1–2:8)

1. Jerusalem’s Plight (1:1–3)

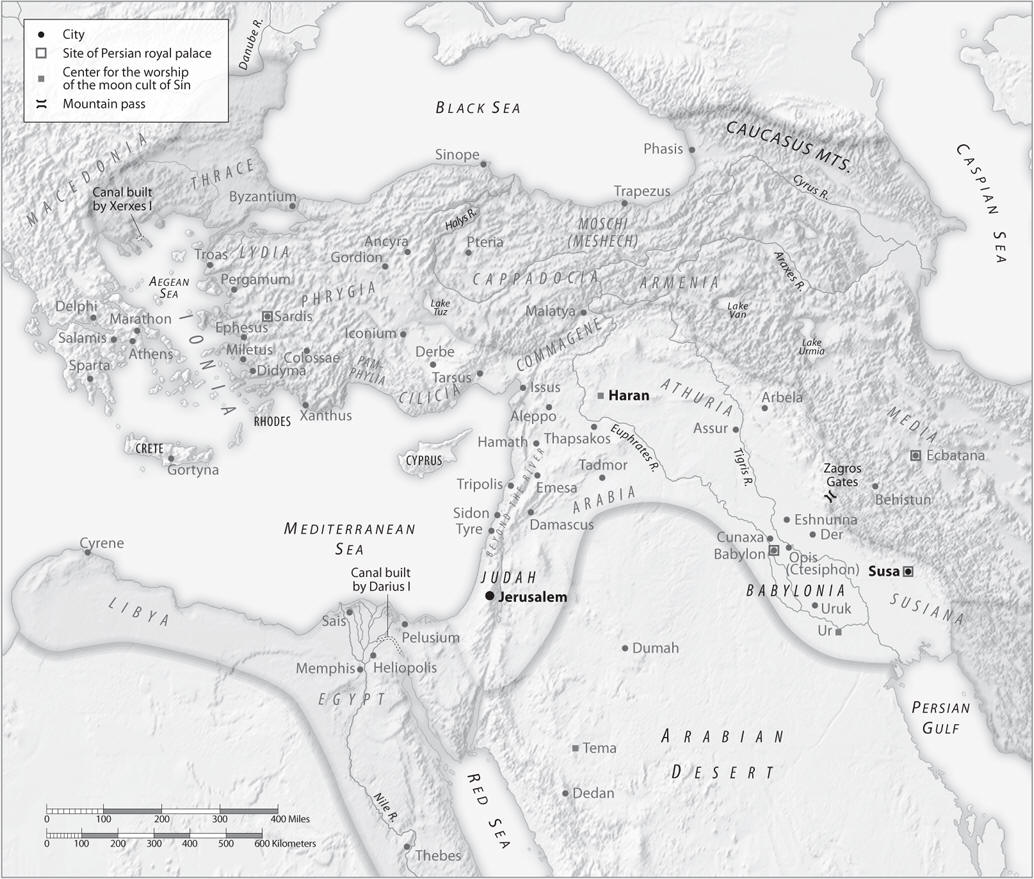

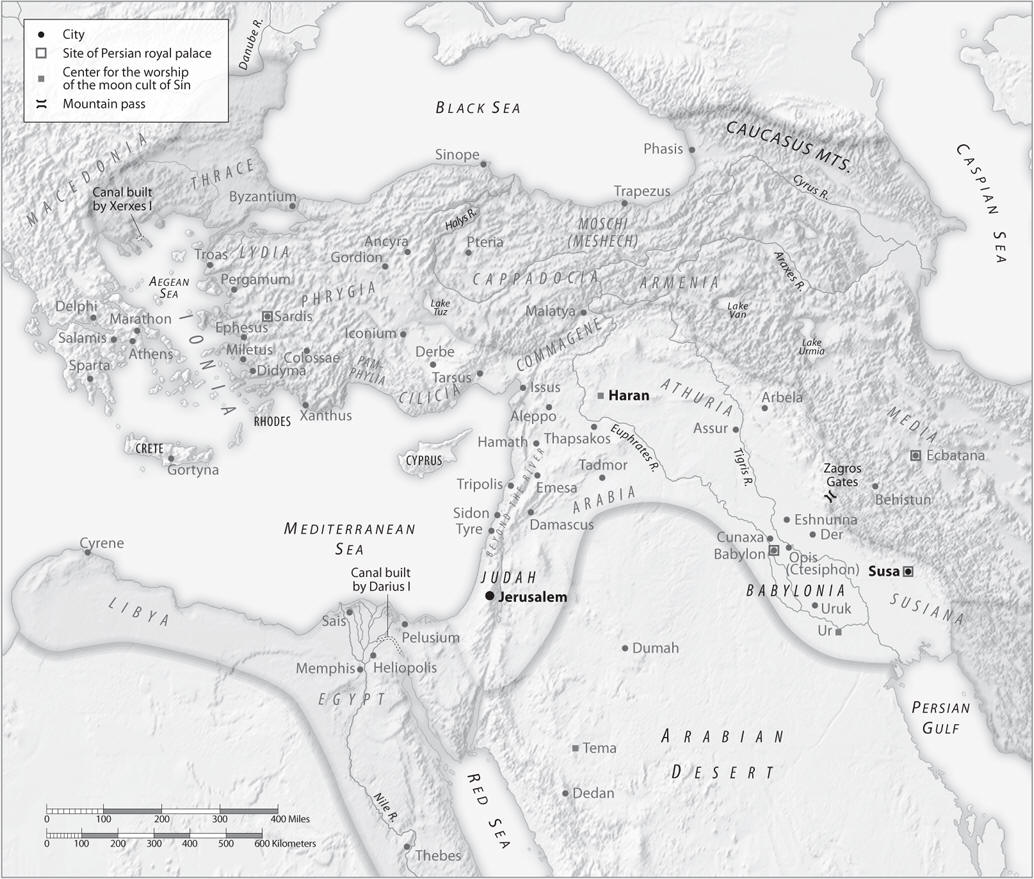

1:1–3. The book claims to be written by Nehemiah the son of Hacaliah. Three Nehemiahs are mentioned in the text: a Jewish exile who returned to Jerusalem in the first return led by Zerubbabel and Joshua, in 538 BC (7:7); the son of Azbuk who was a local official (3:16), and Nehemiah son of Hacaliah, narrator of the book bearing his name. For more on authorship, see Introduction. The month of Chislev of the Jewish calendar corresponds to the period from about December 5 to January 3. The twentieth year refers to the twentieth year of the reign of Artaxerxes, which would place the events of the opening verses of Nehemiah in December of 445 BC. There is some controversy regarding the accuracy of the dates in the first two chapters of Nehemiah; for more information, see the comments on 2:1. Susa the capitol has caused some confusion among interpreters. It is well known that the capitol of the Persian Empire was the city of Babylon, taken over by the Persians when they conquered the Babylonian empire in 538 BC. Susa, however, served as a winter palace and fortress for Persian kings, and was located east of the city of Babylon and about 150 miles north of the Persian Gulf. Fellow exile Daniel experienced a vision of himself in Susa (Dn 8:2). Susa is likewise the setting for the story of Esther.

Hanani, one of my brothers was likely an actual blood brother or relative of Nehemiah, and there is record of a Jewish administrator of that name in Jerusalem during this period. It is unknown whether that person is the figure mentioned here. As for the Jews who had escaped and had survived the captivity, Nehemiah inquires about those who had earlier returned from exile, and is surprised that they remain in a distressing situation in Jerusalem. On the fall of Jerusalem and the subsequent exile, see Jr 39. and 2Kg 24. During the reign of the Persian kings, the Holy Land was subdivided into four administrative districts, with Jerusalem serving as the local capitol of Judah. It was in this period after the exile that the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob began to be known as "Jews." The distress of Jerusalem extends to the remnant (the people God had preserved through the exile and brought back to Jerusalem), the gates, and the wall. It is significant that the bulk of the book of Nehemiah focuses more on the rebuilding of the remnant than on the walls, indicating that God’s greater desire was the faithfulness and obedience of His people.

2. Nehemiah’s Prayer (1:4–11)

1:4–5. Nehemiah seems surprised by the report, coming as it does nearly a century after the first return of exiles in 538 BC. When Nehemiah identifies with those who love [God] and keep His commandments (v. 5), he is bringing to mind the promise of God’s faithfulness to his people expressed in the Mosaic covenant (see specifically the Ten Commandments, the first commandment in Ex 20:6 being reflected here in Nehemiah’s prayer about "loving God" in v. 5).

1:6. In the beginning of Nehemiah’s prayer he confesses the sins of the sons of Israel, including his own. One of the main sins that had led to Israel’s exile was idolatry (e.g., 2 Kg 17:7–20). It has been said that the Babylonian captivity "cured" Israel of her centuries-long struggle with idolatry. Though the post-exilic Jewish religion had its problems (such as the legalism of Jesus’ day), idolatry does not seem to have been among them (the end of idolatry was foretold in Hs 3:3–4).

1:7–10. The commandments, statutes, and ordinances (v. 7) of Moses refer not only to the Ten Commandments but to the whole of the Pentateuch, delivered explicitly to Israel before the initial conquest of the promised land. Along with idolatry, Israel’s failure to honor the law led to God’s judgment in the exile (cf. Lv 26). Nehemiah knows that restoration to and security in the land will require renewed adherence to the Mosaic covenant. This renewal, and the related "reconquest" of Canaan under Nehemiah, is the major theme of the book. In vv. 8–9 Nehemiah explicitly quotes Dt 30:1–4 (also Lv 26:33), effectively Moses’ last words to Israel before Joshua’s conquest, and in so doing identifies with the promises of restoration to the land, which would partly take place under Nehemiah’s own leadership. The regular mention of the people You [God] redeemed by Your great power and by Your strong hand (v. 10) is the language of Passover and the exodus (Ex 12–14).

1:11. A cupbearer (v. 11) was not a waiter, but a highly trusted servant. Just as modern Secret Service agents constantly guard the US president, so the cupbearer was ever present. Given the history of assassinations in the Persian court, Nehemiah’s job was to be sure the wine was not poisoned. Additionally, he did more than protect—he also served as companion and confidant to the king, much like a modern "counsel to the president."

3. Artaxerxes’ Permission (2:1–8)

2:1–4. The month of Nisan (v. 1, March/April) is the first month of the Jewish calendar; this presents some difficulty reconciling Nehemiah’s audience with the king still in the twentieth year with the earlier report from Jerusalem in the ninth month, Chislev (1:1). Apparently, Nehemiah is using a Persian dating system that likely calculated the king’s reign from the precise month that it began, so that a single year in his reign would span two normal calendar years. Thus the events of v. 1 still take place in the twentieth year of King Artaxerxes, though they occur in the following Jewish calendar year. The text says that Nehemiah’s request to Artaxerxes is made three months after the report from Jerusalem, in March/April 444 BC.

Nehemiah was afraid (v. 2) for two reasons. First, it is assumed that to live in the presence of the king is an unqualified privilege and pleasure, so to exhibit any negative expression is to dishonor the king (cf. Est 4:11; 5:2–3). Second, Nehemiah is about to ask the king to permit the rebuilding of Jerusalem in direct contravention of his earlier decree to cease such labor (Ezr 4:21). Nehemiah does not really want Artaxerxes to live forever (v. 3)—this is just the proper way to address Persian royalty. He credits his sad face to a politically safe cause: the poor condition of his native land. When the king invites Nehemiah’s request, he prays to the God of heaven (v. 4)—but this is not a sudden and surprised prayer, but instead a recapitulation of the sustained prayer of 1:4–11 (that is, his "quick" prayer in 2:4 is basically a "Now, please, Lord" based on the earlier prayer).

2:5–8. Nehemiah had the extended three months of prayer before making his request of the king, so he was prepared with exactly the correct petition and precisely the appropriate answers to Artaxerxes’ expected questions. He knew he would need the king’s support for security (allow me to pass through, v. 7) and building supplies (beams for the gates of the fortress, the wall of the city, the house, v. 8). With striking understatement the text says that the king granted the requests. In so doing he committed financial, political, and military support to the rebuilding of Jerusalem. Perhaps more significantly, this decree initiates one of the most important prophetic timelines for the coming of Messiah. Daniel had previously prophesied that "from the issuing of a decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem until Messiah the Prince there will be seven weeks and sixty-two weeks" (see Dn 9:25 and the comments on Dn 9:24–27).

This passage offers several points of theological and practical significance. Extended times of prayer, and delayed answers from God may be a manifestation of grace to make us ready for when the time is right. If Nehemiah had rushed impetuously and impatiently to Artaxerxes upon receiving the report from Jerusalem, he would have been ill prepared to answer thoughtfully when the king invited his request. Similarly, Nehemiah’s years spent becoming and serving as a cupbearer were not wasted. He was being prepared for a distinct ministry, much like Esther being readied "for such a time as this" (Est 4:14). It is less important what title one bears, or how one intends to serve God, than what one does when the opportunity for service is presented. Nehemiah’s years at court not only gave him access to the king at a time of need, but also equipped him for the political and administrative challenges he was about to encounter.

B. Nehemiah Travels to Jerusalem and Surveys the Situation (2:9–20)

1. Travel to Jerusalem (2:9–10)

2:9–10. Nehemiah’s pathway from Susa to Jerusalem mirrors that of Abram’s journey: across the Fertile Crescent from Babylon, northwest to Haran, and then west and south into Judah and Jerusalem. Beyond the River (v. 9) refers to the lands west of the Euphrates, the horizon of Babylonia’s traditional realm. The letters from the king were validated by officers and horsemen from the king. Sanballat (v. 10) was governor, subject to Artaxerxes, over Samaria, the region or province north of Jerusalem. Tobiah was governor (one of many of this powerful family) of Ammon, east of the Jordan River. Judah in these days was underserved and underrepresented; the appointment of a governor and champion (seeking the welfare) of Judah, Jerusalem, and the Jewish people represented a corresponding diminishing of the power of the other governors in the area. Hence, their adverse reaction to these new developments under Nehemiah is understandable although certainly inappropriate.

The Persian Empire

Adapted from The New Moody Atlas of the Bible. Copyright © 2009 The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago.

2. Surveying the Walls of Jerusalem (2:11–16)

2:11–12. Waiting three days (v. 11) may have given Nehemiah time to settle into his home and identify the local leaders and power structures. Waiting a few days may also have begun to lull the opposition into thinking that he was not any immediate threat. Verse 12 and v. 16 serve to bracket the intervening verses, and emphasize that Nehemiah had not told anyone his intentions (v. 12), that is, what God had put into his heart. After being in the land and city for nearly 100 years, the disrepair of the walls and corresponding spiritual poverty of the people had sadly become normative. Nehemiah’s audacious intent to reverse both of those conditions would require a clear understanding of the situation and a specific plan to address it. Scouting the walls alone in secret gave him the time to come up with a plan to follow. That there is no animal with him (i.e., he walked inconspicuously) is in contrast to v. 9 where Nehemiah travels with the king’s horsemen.

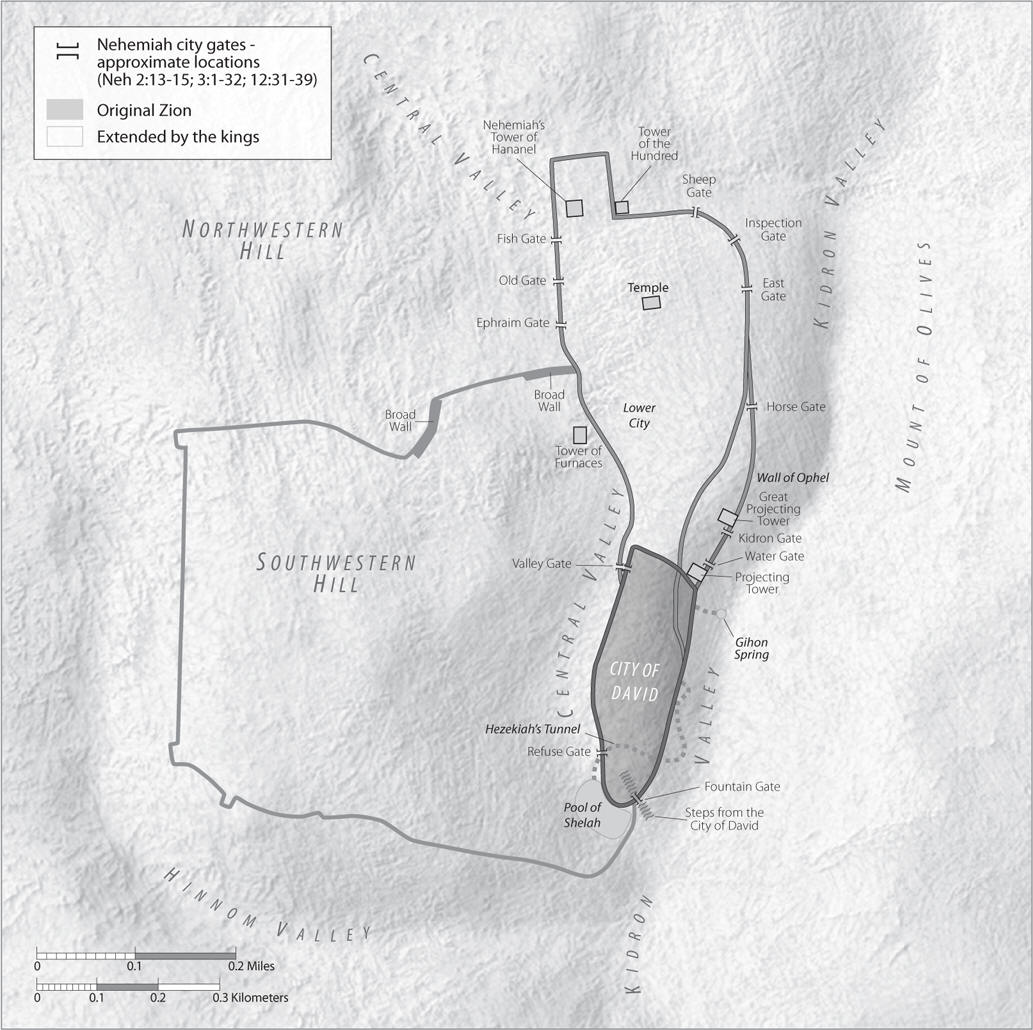

2:13–16. Nehemiah does not circumnavigate the whole of Jerusalem, but only surveys the southern portion. The Valley Gate (v. 13) faced southwest towards the Hinnom Valley; the Dragon’s Well likely refers to a spring at the junction of the Hinnom and Kidron Valleys on the southeast edge of Jerusalem. The Dung Gate or Refuse Gate would have been at the southernmost tip of the city, as deep into the valley and far from the temple area to the north as possible, accessing the garbage dump to the south. The Fountain Gate (v. 14) faced southeast, toward the Kidron Valley, and the King’s Pool may be a reference to the Pool of Siloam (cf. Jn 9) at the southern edge of Jerusalem. The state of the walls, gates, and approaches to the city were so poor that even a single horse was unable to navigate the area. Not only is this a dangerous situation (enemies can approach unobserved, criminals can slink in and out of the city), but also it is a reflection of a people without self-respect or hope. Compare this to the earlier and later comments (in Neh 1:3 and 2:17) that the people suffer reproach. In keeping with the book’s theme of the reconquest of Canaan (see the Introduction), the author may have included the record of Nehemiah’s puzzling nighttime inspection of the walls as a parallel to the spies’ secret visit to Jericho before Joshua’s conquest (cf. Nm 13 and Jos 2).

3. Beginning the Work of Rebuilding (2:17–20)

2:17–18. The reproach of the people (v. 17; cf. 1:3) is personal shame, corporate disgrace, and a reflection on the nation and its God. Here Nehemiah announces his bold plan to rebuild the wall of Jerusalem. It may be that although the local governors knew of Nehemiah’s royal support, the people and priests did not yet know of his intent to rebuild the city. Even upon hearing of it, they may have felt the task was impossible, or would be merely more of the same in accordance with previous failed attempts. However, upon hearing of the king’s direct sponsorship of the project, and understanding that this must indeed be an instance of divine provision (the hand of my God had been favorable, v. 18) they were strengthened to do the good work.

2:19–20. Sanballat and Tobiah begin a public mockery of the work (v. 19). They are joined by Geshem the Arab, whose province comprised the regions south of Judah, thereby completing the circle of political opposition around Nehemiah and Jerusalem. This collection of opponents recalls the nemeses of Israel from their time of wandering and conquest: Ammon (Dt 23) and Jericho with Samaria (Joshua). The meaning of portion includes the idea of inheritance as well as ownership. Portion occurs more often in the book of Joshua than any other OT book (Jos 14:4; 15:13; 17:14; 19:9; 22:25), and is used here to signal the reclaiming of Israel’s inheritance under Nehemiah. Further, talk here of an inheritance immediately precedes the assigning of sections of the walls to various families, paralleling the division of the land to various tribes and clans under Joshua. Nehemiah looked beyond what Jerusalem was in his day (a wrecked town) to what it would become—a great city in which these opponents would have no part.

Though this section is historical, it has practical application for today. There is such a thing as a proper use of secular power, and practical wisdom. Certainly Nehemiah was convinced that the success of his endeavors would come by the abiding hand and favor of God; however, he did not presume upon the favor of God by acting foolishly and assuming that God would work everything out. Instead, he marshaled his resources, acted circumspectly, and then was prepared to act boldly when the proper time came. Also, those who expect to enjoy a portion in God’s blessing (in contrast to those opponents who have no such expectation) should also anticipate taking a portion of the labor, as the following chapter illustrates with the rebuilding of the wall.

II. The Rebuilding of the Walls (3:1–6:19)

A. Nehemiah Leads the Rebuilding of the Walls (3:1–32)

Having previously stated that "the God of heaven will give us success" (2:20), the purpose of this chapter is to demonstrate the evidence of that claim. It recounts the builders and their tasks in reconstructing the walls and gates of Jerusalem. The description proceeds geographically in a counterclockwise direction around the city, starting and ending at its northeastern corner near the temple area. Though the whole of the rebuilding requires 52 days to complete (6:15), this chapter anticipates the completion of the work, as described in chaps. 4 through 6. The workers came from many cities and towns, spanning the whole of Judea, indicating the broad popular support and political success Nehemiah enjoyed.

3:1–2. This is the first mention of Eliashib the high priest, the grandson of Jeshua, the high priest during the initial return under Zerubbabel (cf. Ezr 3; see also Neh 12:10–12). Fittingly, he and his priests are mentioned first, and the account begins with the rebuilding of the Sheep Gate, at the eastern edge of the north wall of the city. It was through this important gate that sacrificial sheep would enter the temple courts. The Tower of the Hundred and the Tower of Hananel (perhaps the "fortress … by the temple" of 2:8) were fortifications on the north side of the city, as this area did not enjoy the natural protection of a steep ascent. Also prominent by their early mention are the men of Jericho—recalling, perhaps, that Joshua’s conquest began with the defeat of Jericho and now her men are numbered with Israel.

Jerusalem during Nehemiah’s Rebuilding of the Walls

Adapted from The New Moody Atlas of the Bible. Copyright © 2009 The Moody Bible Institute of Chicago.

3:3–5. The Fish Gate was on the northwest side of the city, in the direction of the "Great Sea" (the Mediterranean), and allowed easy passage to the city’s fish market. This gate also led out into the territory of Ephraim, and so may be another name for the Gate of Ephraim (8:16; 12:39). Many builders are listed here, and in the remainder of the chapter, who are otherwise unmentioned in Scripture and little known to us. It would be a mistake to try to draw theological significance from the etymology of their names. The Tekoites (citizens of Tekoa, about five miles southeast of Jerusalem, Amos’ hometown) participate, but their nobles do not. Perhaps these nobles feared the wrath of Geshem the Arab (2:19).

3:6–12. Towards the northern end of the west wall is the Old Gate (v. 6). That its beams, doors, bolts and bars are mentioned indicates that the gate was wholly restored. Explicitly mentioned are the men of Gibeon (v. 7), for their work on the western wall. Known from the Joshua narrative as those who deceived Joshua and were thus forced into subjugation (Jos 9:22–27), they remained conquered, as did the men of Jericho in Neh. 3:2. The governor of the province beyond the River (possibly Nehemiah) has a residence or "seat" along the wall, which these men repaired. Also singled out are the goldsmiths and perfumers (v. 8) for their work toward the Broad Wall. At this point and in the following verses, it becomes evident that, by the participation of the priests, the conquered people, the common Israelites, and the wealthier professionals (the goldsmiths and perfumers), this labor is genuinely a community effort and requires everyone’s active contribution. Along with many others, the officials of Jerusalem (vv. 9, 12), including some daughters (v. 12), worked to rebuild. Evidently, everyone was capable of making some important contribution to the work. The Tower of Furnaces (v. 11) is the section of the city wherein baking ovens and/or pottery kilns would be located, indicating the participation of these guilds as well (with the goldsmiths and perfumers mentioned earlier, v. 8).

3:13–14. The Valley Gate through which Nehemiah began his nighttime inspection (2:13) is so named because it leads to the Tyropoeon Valley to the west of Jerusalem. This southwesterly section of the wall and its gates seemed to be in the best repair, as indicated by Nehemiah’s ability to traverse this section on horseback in the preceding chapter, and by the relatively few workers mentioned for a large section of the wall (a thousand cubits, or 500 yards) to the Refuse Gate. This is the section least threatened geographically by Sanballat, Tobiah, and Geshem, which may explain its relatively good condition (or its relatively low priority) for allocating workers and resources for repair. The Refuse Gate, sometimes called the Dung Gate, is at the southernmost point of the city, farthest from the temple precinct and allowing the most immediate access downhill and downstream from the city. It is a bad idea to discard rubbish and dung upstream from one’s water source.

3:15–27. The Fountain Gate (v. 15) is also at the far southern point of the city, probably oriented toward the Kidron Valley along the eastern wall as the wall begins its northerly course. The Pool of Shelah may be identified with the NT Pool of Siloam (Jn 9:7) into which the water from Hezekiah’s tunnel flowed, apparently part of a park or garden area (the king’s garden) in Jerusalem; this area would be part of the original city of David. The Nehemiah mentioned in Neh 3:16 is not the narrator of the book (see 1:1). This area, including the tombs of David, the artificial pool (v. 16; possibly the "King’s Pool" of 2:14), and the house of the mighty men mark the limits of Nehemiah’s prior nighttime inspection. Apparently this section of the city recalls Israel’s golden age under David and Solomon. The work on this eastern wall is delineated now primarily from house to house rather than gate to gate, reflecting some large distances between gates to the east. This is understandable as the eastern slope of Mount Moriah (upon which Jerusalem was built) is quite steep and does not permit many roads allowing entrance into the city. The Levites build as well (v. 17), paralleling their brothers the priests (3:1, 22), showing again that all tribes share in this labor.

3:28–32. The last segment of the wall completes the circuit of the city, along the temple courts and back to the Sheep Gate in the northeast corner. The Horse Gate (v. 28; cf. 2Ch 23:15) allowed access to the former royal courts (horses were a mark and measure of wealth). The East Gate (v. 29; cf. Ezk 10:19) may be the predecessor to the current Golden Gate of Jerusalem. One of the builders, Meshullam (v. 30), is later identified (6:18) as a relative by marriage to Tobiah, one of Nehemiah’s constant nemeses. Ultimately, the end of the book finds Tobiah actually living in the temple storerooms whose construction is described here (13:4–9).

The various workers here—priests, goldsmiths, prominent political families—underscore once more the complete participation of the community in the labor. Finally, the Inspection Gate (v. 31) is listed, so named possibly due to its proximity to the temple. The faithful would bring their sacrifices through this gate, and the animals had to "pass inspection" according to the dictates of the law (see for example Dt 17:1); alternatively, this area may have been the place of "muster" or "inspection" for the guard or army (as the word is used in 2Sm 24:9).

As noted previously, the book of Nehemiah serves to recapitulate much of the history of Israel. This section is reminiscent of the conquest of Canaan led by Joshua, and serves a similar function for the people of Judah. Just as the conquest would not be complete, and Israel would not fully possess the land in peace, unless each tribe secured its own assignment in the land, so also the walls would not be complete and none of the citizens of Jerusalem would be safe unless each family or group successfully completed the rebuilding of their section of the wall.

Additionally, this project brings to mind the saying that "a chain is only as strong as its weakest link." The same can be said for Jerusalem’s walls: they are only as secure as their weakest section. Obviously, no builder in the city can take undue pride in the significance of his task, but must recognize how critical every section is. This anticipates the NT attitude toward the interdependence of the varying members of the Church. Sometimes the Church is described with a building metaphor, where every believer is a living stone being built together into a temple in which God takes delight to dwell (Eph 2:21–22). The Church is also described as a "body," and Paul instructs his readers that every part of the body is significant, even critical, to the proper function of the whole (1Co 12:14–26).

B. Opposition: the Military Challenge (4:1–23)

The following report about opposition was designed to highlight the success God was granting. At the end of chap. 2, Nehemiah claimed that God "will give us success" (2:20). Chapter 3 demonstrated the success God had granted. Here in chap. 4, the point is to emphasize that, even with opposition, success did indeed come from the Lord. At the heart of Nehemiah and the people’s victory lay this crucial fact: "we prayed to our God" (4:9).

1. The Mockery of the Opposition (4:1–6)

4:1–3. On Sanballat and Tobiah (v. 3) see comments on 2:9–10 and 2:19–20. Sanballat’s fury (v. 1) literally made him "hot" and he was once more very angry—as he was in 2:19 when he heard of Nehemiah’s plans. Disproportionate anger remains a common response to the work of God and to His people. Mockery is often enough to dissuade people who are only weakly committed to a task. Sanballat’s mockery takes the form of five questions, and reflects a keen understanding of the weaknesses of the human psyche. The forms his ridicule takes remain effective discouragers today. He first asked, What are these feeble Jews doing? Calling the Jewish people feeble (v. 2) is objectively accurate of those who had returned, surrounded by enemies as they were and in economically tenuous circumstances.

His second question, "Can they restore it by themselves (HCSB)?" gives voice to the enormity of the task. Sometimes verbalizing an objective reveals its audacity. The third question, Can they offer sacrifices? has a twofold effect: it points out the disconnection between the walls and the spiritual work of the temple, and mocks the devotion of the Jewish people. There are those today who agree that the Church ought be concerned only about spiritual work and ignore tasks of a secular nature. Fourth, with the question Can they finish in a day? Sanballat misrepresented the time frame, again attempting to demoralize the people. Many worthwhile projects cannot be completed in a day; God’s people must be on guard against an impatience that makes them unwilling to sustain a difficult task. Finally, Sanballat wonders whether the Jewish people can build a wall using burned stones weakened by the fires of Nebuchadnezzar’s assaults. Here he again misrepresents their challenge. It was not as bad as that, with many available stones perfectly suitable for (re)use in the walls.

These questions bring to mind the spies’ initial report of Canaan, that its people were "giants," or of the daily discouragement of the army of Israel when subjected to Goliath’s taunts. Sanballat began by saying the returned number of Jewish people was too small (v. 2). He now concludes by saying their task was too great.

Tobiah’s mockery in v. 3 undermines itself. If the walls were so weak that even a small animal would topple them, then Jerusalem’s enemies should have no worries. The concern of Sanballat, Tobiah, and others should have encouraged the Jewish builders that their labor was significant.

4:4–6. Once more, Nehemiah prays and then he works. His is an "imprecatory" prayer, asking God to judge and punish the enemies of God’s people. Compare Pss 5, 28, 31, 35, 58, 59, 69, 79, 83, 109, 137, 139, 140, as well as Jeremiah’s prayers (in this same city!), particularly in Jr 11, 15, 17, 18. Note particularly the close parallel between Neh 4:5 and Jr 18:23. When Nehemiah notes that the people are despised (v. 4), he implies that if God’s people are despised, it is really God who is being mocked. As such, his prayer is that God act on His own behalf. A believer’s attitude and prayer regarding "enemies" ought to be motivated by a concern for God’s name, and not individual reputation.

The theme of reproach returns here (4:4). It is a subtle form of prayer that genuinely looks to the defeat of God’s enemies without seeking to take its own revenge, but instead trusts in God to use many mysterious means to produce His judgment. Compare Habakkuk’s confusion that God would use the Chaldeans to discipline Israel (Hab 1–2). The God who turns the heart of the king and can hurl Babylon in judgment against His own people can certainly intervene on behalf of His people in any age. Despite the mockery of their enemies, and according to the strength that came by prayer, the Jewish people were able to reach the halfway point of the walls’ reconstruction. This seems to have provoked an intensified concern on the part of their enemies, as they began to plot violence. Godly success often begets increased opposition. The people had a mind to work (v. 6). "Mind" here is literally "heart."

2. The Threat of Violence (4:7–15)

4:7–9. In the face of the ridicule of Sanballat, Tobiah, and the others, the Jewish builders sustained their work, prompting their opponents to intensify their opposition with threats of violence. As the breaches began to be closed (v. 7), the window of successful opposition shrank as well. In the face of the opposition, Nehemiah reacts with a spiritual as well as a military response: we prayed to our God and we set up a guard (v. 9). This was an appropriate balance—trusting God for success but taking appropriate action as well. Sanballat hoped to disrupt the work enough (fight and cause a disturbance) to perhaps influence Artaxerxes to withdraw his support for the project (as in Ezr 4:19–22).

4:10–15. The situation was so bleak that the Jewish workers began to sing a song of discouragement (v. 10) even as they labored, ironically echoing the lament of Psalm 137 recently sung in Babylon, longing to return to this very city. The Jews who lived near them (v. 12) refers to the Jewish people who dwelt outside Jerusalem, in geographic proximity to the ring of Israel’s enemies. They brought word of the plotters’ devices: told us ten times might be a literal ten times, or perhaps something repeated several times (cf. Gn 31:7, 41; Nm 14:22). These plots were not in secret—even the reports become a sort of propaganda campaign of discouragement to the people.

Nehemiah reallocated some of his workforce to defense and stationed men … behind the wall and in the exposed places (v. 13) while others continued the work. Ultimately, Nehemiah encouraged the people by first calling them to remember the Lord who is great and awesome (v. 14)—Israel’s best hope has always been in the Lord rather than physical strength—and to be prepared to fight for their families and land. Nehemiah’s do not be afraid of them is reminiscent of Moses’ charge to Israel and Joshua before the conquest in Dt 31:6ff. In the end, it is Israel’s enemies who become discouraged, although Nehemiah is careful to acknowledge that God had frustrated their plan (v. 15).

3. The Renewed Work (4:16–23)

4:16–18. Encouraged by their ongoing success, the Jewish builders applied themselves to the labor with renewed vigor. "Each one to his work" (v. 15) recalls the significance of the labor of each participant. For the remainder of the task, half of Nehemiah’s forces were on constant military alert (with spears, shields, bows, and breastplates), while even the half that continued building did so with the other hand holding a weapon (v. 17). This militarization of all of Israel turns even the mundane task of stonemasonry into a military campaign. Israel is certainly at war, with her captains who were behind the whole house of Judah (v. 16) directing the forces.

4:19–23. Even with this, the forces were spread thinly, so Nehemiah retained a trumpeter to remain near him to summon defenders if enemies arose at a point of weakness. Divine providence and human responsibility are closely juxtaposed: At whatever place you hear the sound of the trumpet, rally to us there. Our God will fight for us (v. 20). This vigilance is epitomized by the scope of readiness throughout the day (from dawn until the stars appeared, v. 21), the complete social strata of Israel (each man with his servant, v. 22), and through every detail of the day (even to [get] water, v. 23). This latter phrase may bring to mind Gideon’s likewise outnumbered army, selected randomly by God even as they drank (see the comments on Jdg 7:1–8). Ultimately, during these critical weeks of construction, the worker-warriors become an armed camp, staying in Jerusalem around the clock—a guard for us by night and a laborer by day.

This passage reminds us that not all opposition is physical—Sanballat’s initial "attacks" were psychological—and that struggles are not always against flesh and blood, but against spiritual forces (cf. Eph 6:12). And often, those who threaten with great bluster are rebuffed by simple confidence in the Lord’s sufficiency. Moreover, perseverance through trials leads to greater successes (as 1Pt 1:7 instructs, perseverance through trials purifies and strengthens faith). Confidence in the Lord does not negate the role of practical and applied wisdom: Nehemiah models what it is to trust God, take wise action, and credit God with any successes that follow. Finally, the demands of faithfulness may include total dedication to the Lord’s cause, all of one’s resources and time, at least for a season.

C. Opposition: the Moral Challenge (5:1–19)

There is a practical piety in the book of Nehemiah. While Nehemiah and the people had confidence in God granting them success, particularly through prayer, they also took up weapons for defense even as they trusted God. In the continuing description of God’s work of rebuilding the walls, though the people take up their own defense (previous chapter), they also need strong leadership. The following two brief narratives about Nehemiah’s godly leadership illustrate this point, reinforcing the importance of practical piety.

1. The Problem of Usury (5:1–13)

a. The People’s Complaint (5:1–5)

5:1–4. In the midst of external opposition from Sanballat and his cohorts, an even more insidious challenge comes from within the Jewish community: the economically oppressed—including their wives—cry out against their Jewish brothers (v. 1). Economic distress comes in many forms. One is a basic lack of food: let us get grain that we may eat and live (v. 2). Another symptom of distress is the mortgaging of property—fields, vineyards, and houses (v. 3). Some of the Jewish people had been back in the land long enough to establish themselves economically, but the present distress was forcing them to forfeit even those meager gains. A combination of growing population, concerns over physical safety, attention to the labor of the walls, and the disrepair of the fields had led to famine. High taxes, such as the king’s tax (v. 4), were a third source of economic distress. Multiple sources recount the oppressive taxes of kings in the ancient Near East. For example, one common estimate is that the Persian king collected twenty million darics per year in taxes (high-quality gold coins introduced by Darius the Great around 500 BC that continued in use until Alexander the Great’s conquests in 330 BC).

5:5. So extreme were the economic challenges that family members, sons and daughters, were sold into bondage to satisfy creditors. Jewish law required that such "hired servants" be released in the seventh year (Dt 15:12–18). A vicious downward spiral prevailed as the people lost possession of their fields and vineyards, and ultimately their own freedom, and lacked the means to repay debts or provide for their families. To some minds, the conditions of restored Israel were worse than those of exiled Israel. At least in Babylon families were together and could live with relative provision. This recalls the complaints of the Jewish people even in the aftermath of the exodus from Egypt, facing the hardships of the wilderness (cf. Nm 14).

b. Nehemiah’s Response (5:6–13)

5:6–8. Nehemiah became very angry (v. 6) because he was focused on the walls and the needs of the city and was shocked that any would capitalize on the hard economic circumstances for personal profit. It is one thing when the threat is external, as with that of Sanballat and Tobiah—that is to be expected. It is much worse when the "threat" to a community is internal. Here Nehemiah contends with the nobles and the rulers (v. 7). He first consulted with himself to be sure that his actions and words would be just and fitting. He held the nobles and rulers up to public censure by calling a great assembly against them. Already Nehemiah has reduced the size of his workforce by separating the people into guards and laborers (4:15–23); now he had to spend precious time by calling everyone away from the work to assemble together. However, both actions increase the effectiveness of the labor, as the people are ultimately freed to labor first in physical, and then in economic, security. Nehemiah accuses the rulers of the most egregious of offenses: usury, the charging of exploitive interest. This is different from a secured loan. (cf. Dt 24:10; Pr 22:26). It is one thing, even an act of mercy perhaps, for one Jewish person to take on another as a bondservant. It is a great tragedy however, as in this case, when Jewish brothers are sold to the nations (v. 8) in order to cover their debts. Nehemiah accuses the nobles and rulers of being indifferent to this tragedy, against which they could not find a word to say.

5:9–13. The testimony of Scripture (Ex 21:8; Dt 23:20) and the courage of "speaking truth to power" was enough to prevent any attempt at self-justification by the nobles and rulers. Believers are reminded that they live on a greater stage than their own interests suggest. They must live righteously before the nations, even our enemies (v. 9). More fundamentally, believers must live in the proper fear of our God. These leaders were valuing their own economic interests ahead of their testimony among the Gentiles and the favor of God.

Nehemiah sets the example (v. 10) by lending money and grain (note that it is lending with interest, not lending without interest, that is condemned). He calls his fellow leaders to join with him in so doing, but without usury. Nehemiah was not giving away his material goods—he expected to be repaid (and those who borrow should expect to repay) in equal value. What he desired was to end the practice of ruinous usury, demanding back more than the value of the thing loaned.

In inflationary times, the collecting of interest may be just if it reflects the current real value of the object lent. In non-inflationary contexts, to charge interest is to demand back more than the value of the amount lent (usury). In inflationary economic contexts, the future "cash value" of an item is higher than the present "cash value," so an equal repayment may in fact require a higher cash repayment. For example, if someone borrows two dollars to buy bread today, and that bread costs three dollars a year later, the "fair" repayment is three dollars a year later. This principle allows the distinguishing today between appropriate interest charges (like savings accounts, CDs, and most home mortgages) and exploitive usury. Of course, best of all is for believers, when they have the resources, to give freely and demand no return (cf. Lk 6:35).

Nehemiah urges the restoration of the possessions lost through the period of economic distress (v. 11). Notably, Nehemiah’s request is couched as an appeal (Please, v. 11), not a demand or command; this is an "in-house" matter among the Jewish people. This reflects the twofold principle that judgment and righteousness begins with the household of God, and that believers must be cautious about expecting, much less demanding, spiritually righteous behavior from those outside the people of God.

The hundredth part (v. 11) is probably a one-percent (perhaps monthly) interest charge, and Nehemiah tells the lenders to return that interest as well as the principal. The settling of these economic matters is ultimately a spiritual issue, as indicated by the involvement of the priests (v. 12). Oaths are ultimately before the all-seeing and all-hearing God. Again, God is the ultimate guarantor of these sacred vows. Nehemiah’s warning (v. 13) is dramatized by shaking out his robes, as one does when removing crumbs or brushing dust off of trousers. The symbolism is clear: may God "shake off" these people if they fail to adhere to that which they agreed to. This sort of "judgment by shaking" is later repeated in Jesus’ instructions to his disciples (Mt 10:14).

The people’s response is threefold: they accepted the terms (Amen), they praised God (v. 13, moral reconciliation freed them for genuine worship), and they did according to this promise (it was not mere "talk").

2. The Example of Nehemiah (5:14–19)

5:14–18. This second narrative demonstrates that God gave the people success through Nehemiah’s sacrificial leadership. Though he had the legal right, Nehemiah did not take from the people during the twelve years of his governorship. (Compare Paul’s words that he worked "night and day so as not to be a burden to any of you," 1Th 2:6, 9.) Some have understood former governors (v. 15) as a reference to the Samaritans and other local rulers. More recent evidence, however, demonstrates that there were governors in Judah before Nehemiah who did take advantage of their position for economic gain. If some of those governors were themselves Jewish, this further highlights Nehemiah’s exasperation with his countrymen. Nehemiah was ultimately concerned about God’s judgment (cf. 5:9, 19) and was guided by the vision for what he was called to accomplish without being distracted or captivated by the opportunities for personal gain afforded by his position (v. 16). The size and scope of Nehemiah’s household and responsibilities is evident (v. 17) by his having one hundred and fifty Jews and officials at his table. Not only did Nehemiah offer "internal" service in leading Judah, he also had an "external" testimony of diplomacy to those who came to us from the nations. Even here, in a narrative closely focused on God’s preservation of the Jewish people, there is a reminder of God’s concern—and the concern of godly people—for all the nations. Despite Jewish economic hardship, the Jewish people, through Nehemiah, were a source of blessing to the nations. Offerings to the governor (the governor’s food allowance, v. 18) are referred to in God’s rebuke of these same Israelites through the prophet Malachi (Mal 1:8).

5:19. Throughout this chapter, Nehemiah’s greatest concern was his consciousness of living before God’s eyes, and for His approval: Remember me, O my God. This theme will be repeated at the close of the book (13:14, 22, 31).

Often the greatest and most discouraging challenges for believers today come from within the community. This is the reason that "judgment [begins] with the household of God" (1Pt 4:17) and that Paul is more concerned about the impurity within the Corinthian church than the corruption outside it (1Co 5:11–13). Furthermore, those who pursue God’s purposes cannot do so for their own material gain (1Tm 3:3; Ti 1:7). Finally, we see in Nehemiah a willing model of righteousness, forfeiting his "rights" to impel others to holiness. True leadership is found more in such actions than in lofty speeches or daring deeds.

D. Finishing the Wall (6:1–19)

Having shown that God used Nehemiah’s servant leadership skills to aid in the success that God was granting in the building project, what follows is designed to show God’s fulfillment of Nehemiah’s claim (2:20) that God would grant them success. Thus, the chapter shows the completion of the wall, even in the midst of threats. The first verse (6:1) serves as an outline of the chapter: the opposition of Sanballat and Geshem (vv. 2–9), Tobiah’s treachery (vv. 10–14), and the dismay of our enemies (vv. 16–19).

1. The Physical Threat (6:1–9)

6:1–4. As the walls neared completion (no breach remained, though Nehemiah had not yet set up the doors in the gates, v. 1), time grew short for effective opposition. The town and plain of Ono (v. 2) was most likely some distance northwest of Jerusalem (seven miles southeast of Lod, near modern Joppa). Sanballat and Geshem were undoubtedly trying to lure Nehemiah far from the security of Jerusalem (though still technically within his territory of Judah) in order to harm or assassinate him. Nehemiah used the great distance, and the time lost to travel, as his reason for not complying. Sanballat’s persistence (five invitations) probably confirmed Nehemiah’s suspicions. Letters in these days were typically sealed to guard their privacy and the authenticity of their source.

6:5–9. The open letter (v. 5) made public the charges against Nehemiah, that he was aspiring to kingship and rebellion against Artaxerxes (v. 6), and was a form of political blackmail. Obviously, the Persian king would tolerate no aspirations of rebellion. It is likely that the true audience for this letter was the Jewish people, in hopes that their fear of Artaxerxes might impel them to take matters into their own hands by restraining Nehemiah. Previous Israelite kings had hired false prophets to testify in their favor (1Kg 11:29–31; 2Kg 9:1–3), which is part of what Amos condemned in his ministry (Am 7:10–17). Nehemiah’s response in v. 8 was direct: the charges are not true; these things have not been done. The intent of the psychological attack (v. 9) was to weaken the morale and resolve of the builders. Although the closing words of v. 9 (O God, strengthen my hands) seem to record a prayer, this is not likely. The "O God" that appears in many English versions (usually in italics) does not appear in the original text. Contrast this with Nehemiah’s known prayers, which typically include "Remember me" or "Remember them." A better translation would be, "I carried on with even greater determination." Indeed, in the face of accelerating opposition, Nehemiah had greater reason than ever to finish the task before his enemies took concrete action.

2. The Political Threat (6:10–14)

6:10–12. The second line of subterfuge against Nehemiah came through Shemaiah, who was confined at home (lit., "shut up," v. 10). Multiple explanations of this difficult phrase have been proposed; the most compelling is that Shemaiah was feigning personal danger to develop a supposed identification with Nehemiah in order to convince him that they needed to flee together to the temple. Shemaiah seems to have had access to the temple, perhaps as a priest; he may also have been recognized as a prophet, which could have been the reason that Nehemiah was willing to visit him. However, like the false prophets of Israel (1Kg 22:5–6), Shemaiah was willing to tailor his messages to serve political and personal ends. It is his counsel here—that Nehemiah believe the false political threat and illegally hide in the temple (Num 18:7)—that convinced Nehemiah that this was no word from God (God had not sent him, v. 12). Nehemiah’s reasons for rejecting the counsel are twofold: a leader (a man like me, v. 11) should not flee from danger, and only priests (i.e., not one such as Nehemiah, who was not a priest) were allowed this intimate access to the temple. Indeed, had Nehemiah taken this counsel and unlawfully barricaded himself in the temple there was a chance his own life would have been forfeit for profaning the sacred space, causing the plots of his enemies to succeed.

6:13–14. Tobiah and Sanballat had initiated this plot. Tobiah had much influence in Jerusalem (see comments on 2:10 and 3:28–32), a point reemphasized in 6:17–19. Here, he was exploiting his resources to trap or discredit the governor. Nehemiah was concerned that he not bear the appearance of guilt or fear by fleeing to the temple, away from weak or nonexistent enemies. Furthermore, Nehemiah recognized that the suggested course of action was not just politically inexpedient, but actually sin (v. 13). This is yet another example of Nehemiah’s knowledge of the Scriptures. The closing of this section includes the familiar formula Remember … (v. 14), here in an imprecatory application against the various individuals opposing the work. Perhaps Nehemiah is applying Dt 32:35 in which the Lord says, "Vengeance is Mine." In summary of the various enemies arranged against him, it is surprising to discover that even Noadiah the prophetess and the rest of the prophets were also arrayed against Nehemiah (v. 14).

3. The Wall Complete (6:15–19)

6:15–16. Finally, though with some understatement, the walls were completed. Elul is the sixth month of the Jewish calendar; the twenty-fifth of Elul is October 27, 445 BC. Fifty-two days (v. 15) is a remarkably low figure for such a large task; its accomplishment reflects well on both the industry of the people and the favor of God, as noted in 6:16. Enemies (v. 16) probably refers to Sanballat and the other named adversaries; nations probably refers to their peoples. The work of Nehemiah and the builders was so rapid that the various plots not withstanding, the nations were astonished and demoralized by the quick completion. Part of what makes this accomplishment astonishing is that any great work requires unselfish cooperation, and such cooperation is often rare (as anyone who serves on a committee can testify!).

The point of these two verses is to show the fulfillment of Nehemiah’s earlier claim that God would grant success (2:20). Now even Nehemiah’s enemies, seeing the wall complete, recognized that this work had been accomplished with the help of our God (v. 16).

6:17–19. The discussion about Tobiah’s letters (vv. 17–19) applies to the whole of the rebuilding period (in those days, v. 17). Nehemiah had accomplished his task in a context marked by constant intrigue and treachery. His experience ranged from those who actively opposed him to those who actively supported him. There were also several positions in between, such as Meshullam (v. 18), who was an active builder of the walls (3:4, 30), even while retaining political ties to Tobiah. Tobiah had secured many political and personal allies through marriage contracts and other personal relationships. These mediators spoke in favor of Tobiah, whereas ironically Tobiah’s own words (via letters to frighten me, v. 19) reinforced Nehemiah’s distrust of him.

No matter how charismatic a speaker is, or how compelling his message, the words must be measured against the word of God. Nehemiah is an early "Berean" (Ac 17:10–13) who rejected Shemaiah’s counsel because it contradicted the revealed Scriptures. The book of Nehemiah is often read as a study in leadership; it could just as well be seen as a catalog of the sorts of opposition common to humanity—personal, physical, psychological, and political. Nehemiah demonstrates the truth of 1Co 10:13: that these temptations are common, and there is always a way for the man of God to act righteously in response.

III. The Rebuilding of the People (7:1–10:39)

A. Genealogies (7:1–73)

Much of Neh 7 matches almost exactly the list of the original returnees in Ezr 2 (see the notes on Ezr 2). With the walls complete, Nehemiah now turns his attention in the second half of his book to the rebuilding of the people who will occupy Jerusalem. To connect his present work with the original returnees from exile, he opens this section with the same list of them that opened Ezra’s account of the first return under Zerubbabel and Jeshua. His purpose in doing so was to demonstrate that the repopulation of Jerusalem would be with genuine Jewish people, truly descended from Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Hence, Nehemiah carefully included this genealogy.

1. The Instructions for Security (7:1–4)

7:1–3. The establishment of civil function was not complete until the gatekeepers, singers, and Levites (v. 1) were appointed to their proper offices. There is some ambiguity in v. 2: how many men did Nehemiah put in charge of Jerusalem? Most English versions suggest two—Nehemiah’s brother Hanani (cf. 1:2) and the citadel commander Hananiah. In favor of this understanding is the slight difference in names as well as the additional description of Hananiah as one who was a faithful man and feared God more than many. Hanani is already known, having been introduced in the first chapter. Hananiah’s suitability for this office is further explained. He had administrative experience as the leader of the fortress, moral excellence (faithful as it related to integrity, literally in Hb., "truthful"), and genuine spirituality (feared God).

Another reading of this verse suggests only one man as "mayor" of Jerusalem. On this interpretation, the verse reads "my brother Hanani, that is, Hananiah, the commander of the citadel." In favor of this reading is the only slight variation in the name (perhaps Hanani was known popularly or familiarly as "Hananiah"), and the unwieldiness of sharing this office. Recall from chap. 3 that Jerusalem was already divided into sub-districts administered by Rephaiah and Shallum (3:9, 12). All things considered, the former interpretation seems preferable—for example, Nehemiah speaks to them (v. 3), indicating a plural audience.

There are multiple readings possible for v. 3 as well. On the one hand, perhaps it reads that the gates are not to be opened until the sun is hot, meaning later in the day than first light. As a measure of heightened security, the gates were not to be opened until the city was completely awake. Alternatively, some suggest the gates were not to be opened "when" the sun is hot—that is, during the heat of the day. The midday period is another time of vulnerability, as guards and others might seek shade as relief from the scorching sun. On either understanding, Nehemiah is instituting unusual security measures owing to the ongoing precariousness of the people in Jerusalem, as well as the very underpopulated condition of the city (to be addressed shortly).

7:4. The city was large only relative to its small population. The area enclosed by the walls was substantially smaller than the former city under Solomon and Hezekiah. The people in it were few, a situation Nehemiah begins to rectify (see 11:1 where residents of the surrounding towns are "drafted" via lottery to move into Jerusalem). Though the houses were not built (v. 4), obviously some houses remained as habitable—just not enough for an appropriately repopulated city. By rediscovering (I found the book of the genealogy, v. 5) and republishing the list of original returnees, Nehemiah is connecting his current project of city-building and populating to the task of the original return. Here Nehemiah is showing that his work is not distinct from God’s plan of restoration but the actual completion of it.

2. The Genealogical Record (7:5–65)

For the most part, 7:5–73 is a nearly identical summary of the same material found in Ezr 2. See also the commentary on Ezra in this volume.

a. The Returned Exiles with Genealogical Records (7:5–60)

7:5–60. Why was so much material, and of such pedantic nature, repeated in the Nehemiah text? Essentially, as noted, the inclusion of this genealogy closely links the earlier returns (under Zerubbabel and Ezra) with this third return and project under Nehemiah’s leadership. Sometimes Nehemiah (the man and the book) is erroneously relegated to merely material and pragmatic concerns such as building walls and administering a city, while Ezra is seen as focused on "spiritual" matters such as the temple and the law. A careful reading of the history of Israel will reveal a consistent association of the people (the nation), its worship (the tabernacle and the temple), the law, and the land. God’s work with the Jewish people demonstrates the regular interrelationship of these concerns. Indeed, the people’s recent exile from the land was occasioned by their idolatry and disobedience to various elements of the law. In the book of Nehemiah, only the initial focus is on the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem (securing "the land" once again), a focus that is substantially complete by the end of chap. 6, less than halfway through the book. This indicates that the book as a whole is as much concerned with the issues of the law, the temple, and the purity of the people as it is with the walls and other critical matters addressed in the first six chapters of the text. Transitioning to concerns such as law, temple, and purity by here recalling the original returnees provides a context and justification for the deeply theological agenda of the remaining balance of the book.

b. The Returned Exiles without Genealogical Records (7:61–65)

7:61–65. Though it seems harsh, those practicing priests who could not establish a family tie to historic and ethnic Israel were excluded from the priesthood in Judah (v. 64). This is consistent with God’s intention to establish a "holy priesthood," sanctified and set apart for particular service (Lv 8–9). This provides the backdrop for the renewed prohibition of mixed marriages to follow later (Neh 13:23–29) in which the Jewish people are required to refrain from marrying foreigners.

3. Summary (7:66–73)

7:66–73. These verses summarize the offerings recorded in Ezr 2:68–69. The discrepancies are probably caused by the "conversion," for example, of the value of things like bowls and garments into cash values. This section ends by noting that many of the people, including priests, Levites, gatekeepers, singers, temple servants, and all Israel (v. 73) remained in the cities surrounding Jerusalem. The need to repopulate the rebuilt city of Jerusalem becomes the focus of chap. 11, but first Nehemiah turns his attention to the spiritual restoration of the people in chaps. 8–10.

Despite the strength of its walls or other fortifications, the real strength of a city or a community is its people. Nehemiah’s work had only begun with the completion of the walls; it would be completed in the construction of a people to occupy the city. Revisiting the list of returnees served to remind the people who they were, and why they were in Judah: to rebuild the temple and the city, and to testify to the power and grace of God.

B. The Public Reading of the Law (8:1–18)

Having highlighted the people’s genealogical descent, showing their genuine Jewish identity, Nehemiah wanted to focus on the spiritual lives of the people. Physical descent from the people of Israel was insufficient without a spiritual relationship with the God of Israel. Thus chaps. 8–10 focus on the spiritual lives of those who had returned, beginning with the input of the Word of God as foundational to their spiritual revitalization.

1. The Reading of the Law (8:1–8)

8:1–4. The whole people gathered … at the square which was in front of the Water Gate (v. 1) rather than the temple court, where only men were allowed. It was on the first day of the seventh month (v. 2), the date of the Feast of Trumpets (Lv 23:23–25; Nm 29:1–6), a festival that began the penitential season for Israel. The blowing of trumpets functioned to call the nation to repentance in preparation for the Day of Atonement nine days later. Ezra was instructed to bring out (and read) the book of the law of Moses (v. 1). The reading of the law may have been part of the origins of the reading cycles that developed in the synagogue shortly thereafter. As Ezra read on this occasion for only six hours or so (see v. 3), he only read portions, not the whole Pentateuch. Assuming the literary and theological agenda of the book of Nehemiah includes an attempt to recapitulate the conquest of Joshua (see also v. 17), a reading of Deuteronomy—Moses’ reproclamation of the law to the people prior to the conquest—would be appropriate.

The makeup of the assembly is noteworthy, consisting of men and women, those who could understand (v. 3). This was not a male-only event, or even an adult event. Children who could understand were present and participating as well (this might count as a challenge to the contemporary practice of excusing children from church services prior to the sermon). From early morning until midday spans about six hours, implying that the people had traveled to Jerusalem from their houses "in their cities" (7:73) early in order to be assembled and ready to hear by daybreak. The wooden podium (v. 4, better "platform") upon which Ezra stood is also translated "tower" (JPS); it is thought to have had a broad, flat surface at the top in order to have space for the men standing with him. The text lists six men on Ezra’s right, and seven on his left, totaling thirteen. This has been a cause of some concern to interpreters because of the lack of symmetry and because the expected number would be twelve. As a result, there has been some disagreement about the significance of the thirteen leaders with Ezra. The most likely explanation is that this is an attempt to associate this event with the conquest. The most prominent gathering of "thirteen" tribes in Israel’s history occurred at the mustering prior to the conquest, recorded in Jos 2–4, where twelve tribes plus the Levites (totaling 13) were assembled (Jos 4:1–10). In the present text, the assembly of thirteen behind Ezra represents the whole of the reconstituted people of Israel in Nehemiah’s day. There is almost certainly a deliberate parallel between the episode at the conquest and this one, thereby associating the present restoration of the land to the past gift of the land.

8:5–8. There appears to have been a specific liturgy of Judah’s worship for this special feast day. As Ezra opened the book … all the people stood up (v. 5), presumably in respect for the Word of God (a practice adopted in many contemporary churches when the Scriptures are read aloud). Ezra led the people in prayer and praise, and they responded with the double Amen (v. 6). Some find in these verses (including vv. 7–8 to follow) the beginnings of the synagogue system that would figure prominently in the NT because here is a service of worship and biblical instruction happening outside of (but close to) the temple courts. (For some reason, many contemporary churches that adopt the practice of standing for the reading of the Word do not also adopt the practice of bowing low and worshiping the Lord with their faces to the ground, v. 6.) In vv. 7–8, a different group of men who were Levites (again numbering thirteen) dispersed among the people and explained the law to the people … giving them the sense. It seems that after Ezra would read, these men would explain, answer questions, and address issues of application. Also, because the people now spoke Aramaic, the Levites would have needed to translate or paraphrase the meaning of the Hebrew text. This pattern of assembly in smaller groups for the reading and discussion of the law became the basis of Israel’s later synagogue system, as well as for Bible study and Sunday school classes for contemporary believers.

2. The Sacred Feast (8:9–12)

8:9–12. The initial response to the law was one of grief, likely because of the penitential day and also the realization of how much of the law had been disobeyed. It was so much that Ezra and Nehemiah had to intervene and encourage the people to celebrate instead: This day is holy to the Lord your God; do not mourn or weep (v. 9). It was a reminder that this holy day, the Feast of Trumpets, was a festival of joy as well. This suggests that "holy" need not equal "somber." Indeed, the people were commanded to go and eat, drink, and send portions (to those without the means to do so—him who has nothing prepared, v. 10). These words are counter to the situation Paul later discovers in Corinth, where the celebration of the Christian love feast had become an occasion of excess for the wealthy and exclusion for the poor (see the comments on 1Co 11:17–22). Celebration of God’s grace should be inclusive of those without the same means to celebrate. Further, there is an appropriate consumption of fat (foods) and sweet drinks, against those who think that godliness requires abstaining from all physical and sensory pleasures. The people responded with great joy (v. 17) when they actually understood the words of the law. A right understanding of God’s law, and the grace it contains, should lead to joy.

3. The Feast of Booths (8:13–18)

8:13–18. On the second day of the (seventh) month, the people found in the law instructions concerning the Feast of Booths (Tabernacles) (Lv 23:33–44; Dt 16:13–16), and immediately reinstituted the celebration. There is some thought here that they began this celebration a few days too early; the feast was supposed to begin on the fifteenth day of the month and last for eight days. More likely, the text here records the timely discovery of the instructions for the feast, which the people were able to appropriately celebrate beginning two weeks later. When the text notes that the people kept the Feast of Booths, it does not say that this was the first time they had done so in centuries (v. 17); indeed, there are biblical accounts of various Booths celebrations throughout Israel’s history (Jdg 21:19; 1Sm 1:3; 1Kg 8:2; Ezr 3:4; Zch 14:16). However, Booths had not been celebrated "like this" (NIV) since the days of Joshua the son of Nun (v. 17). Perhaps the distinctive relates to the "correctness" of the celebration, or the extent of the joy on this occasion. In any event, the author once more draws the reader’s attention to the correspondence between the conquest of Joshua and the reconquest of Nehemiah. Each day included a reading from the law (perhaps in this context Ezra was able to read through the whole of it), as well as ongoing celebrations.

This eighth chapter of Nehemiah contains a surprising amount of historic precedent, laying the groundwork for the teaching and worship of a more geographically diverse Israel in the NT period (the synagogue system), and ultimately much of the shape of early and contemporary Christian worship. From Israel’s earliest days the people had been instructed that the "book of the law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night" (Jos 1:8). By the time of the return from exile Israel had fallen far from this lofty standard, even to the point of needing to rediscover and reinstitute the law itself. In the intervening years before the coming of Jesus the Messiah, the Jewish people sustained this attention to the Scriptures so that Jesus and the apostles were able to initiate their own ministries by entering into synagogues and reasoning from the Scriptures to proclaim the fulfillment of them in Jesus. Admittedly, however, this attention to the Hebrew Scriptures had become tragically obscured by the religious leaders’ obsession with oral tradition (see the comments on Mt 15:1–20). This "Scripture-centered" faith has remained a hallmark of the true people of God for the last 2,400 years.

C. The Confession and History of Israel (9:1–37)

The message of chap. 9 continues the focus on the spiritual lives of those who had returned (chaps. 8–10). The author moves from the nation needing the input of the Word of God as a foundation for their spiritual revitalization to their need for genuine repentance to renew their walk with their God (chap. 9). Based on the reproclamation of the law and the reinstitution of Jewish ceremonial and celebratory practices like the Feast of Booths (Neh 8), the Jewish people realize they have broken covenant with God and then seek to reestablish this sacred covenant (chap. 10). Preparatory to the covenant renewal is the assembling of the people and a recitation of Jewish history here in chap. 9, which is an account of God’s repeated grace and their repeated rebellion, culminating with a confession of their corporate national sin.

1. The Assembly of the Levites and People (9:1–5)

9:1–3. Despite the temporary celebration of Booths at the close of the prior chapter, the returned nation’s need for confession and repentance remained, as well as a rededication to covenant faithfulness. The twenty-fourth day of [that same] month was two days after the end of Booths. Sackcloth was a rough material made of goat’s hair; dirt was also a sign of shame and mourning, in this case for the sins of the people. The confession was exclusive to the community, so Israel separated themselves from all foreigners (v. 2) since God’s covenant had been with Abraham and his descendants (see vv. 7–8 to follow). There is a close connection between the Word of God (they read from the book of the law for three hours), and the application that follows (they confessed and worshiped for three hours). An understanding of Scripture leads to a realization and acknowledgement of estrangement from God (confession), as well as the access available to Him by grace (worship).

9:4–5. Surprisingly, the spiritual leaders of the nation were not singled out (cf. chaps. 4–5) until after this description of corporate confession and worship. This reminds us that a relationship with God is ultimately personal, and not one that can be maintained by the vicarious actions of spiritual leaders. Here, it is the Levites (priestly descendants of the tribe of Levi) who assume a leadership role; in the chapter to follow, as the renewed covenant includes political and administrative commitments, Nehemiah and other governing officials are recognized as well. These Levites led the worship in two groups, with some members (five) participating in both.

2. Creation and the Call of Abraham (9:6–8)