10

FIRST CORINTHIANS

Writer

Very little question is raised about the Pauline authorship of this book. Both at the beginning and end of the book, the author identified himself as Paul (1:1; 16:21). He claimed to be an apostle (1:1; 4:9; 9:1; 15:9) and to have seen the resurrected Christ (9:1; 15:8). Both of these assertions correspond to Paul’s life history, recorded both by him elsewhere (Gal. 1:1, 12) and by Luke (Acts 9:1–16; 14:14). He looked upon Timothy in a spiritual father-son relationship (4:17; cf. 1 Tim. 1:2). He used himself and Apollos, both prominent in the establishment of the Corinthian church, as illustrations of the proper functions of ministers (1:12; 3:4–5; 4:6; cf. Acts 18:24–28). Finally, he disclosed that he had preached in Corinth (2:1–5) and that he had laid the foundation of the church (3:10). This could only refer to Paul’s visit to Corinth during his second missionary journey (Acts 18:1–18). All of these points, added up together, make a strong case for Pauline authorship.

The writings of these Church Fathers confirm the early tradition that this book was canonical and written by Paul: Clement of Rome, Didache, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Ignatius, Clement of Alexandria, and Tertullian. A full description of Paul’s life was discussed earlier (see pp. 176–79).

City of Corinth

A check of the map will show that Corinth was located on a narrow strip of land, called an isthmus, connecting the Peloponnesus with northern Greece. This isthmus also formed the land bridge between the Aegean and the Adriatic seas. Located forty miles west of Athens, Corinth was the capital of this southern province called Achaia. The Romans had destroyed the city in 146 b.c., but because its location was so important, they later rebuilt it under Julius Caesar in 46 b.c. By the time Paul arrived in the city (a.d. 50–52), the city had grown to a population of 500,000. Today only the ruins of the city remain.

The Corinth Canal, near the site of ancient Corinth. The canal, completed in 1893, was partially excavated in ancient times under Nero with forced labor including Jewish captives.

In that day Corinth was the crossroads for travel and commerce, both north and south for the Greek peninsula and east and west from Rome to the Near East. It had two seaports, Cenchrea on the Aegean Sea to the east and Lechaeum on the edge of the Gulf of Corinth to the west. Commercial ships, instead of sailing around the dangerous southern tip of Greece, were portaged across the isthmus from one port to the other. This saved time and was less risky. Thus Corinth became a city of wealth and pleasure. People went there with money to spend and to indulge themselves in varied pleasures.

On the highest point in the city stood the pagan temple of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, full of religious prostitutes to serve the wishes of its devotees. These women also entertained in the night life of the city. Also located at Corinth was a stadium where athletic contests, next best to the Greek Olympics, were held every two years. Although Corinth was influenced by the philosophy of Athens, it never became a center of intellectual learning. The citizens and the tourists were too busy making and spending money to do much rationalistic speculation. Because it was a mercantile center, all kinds of people settled there: Romans, Greeks, and Jews. Corinth became a cosmopolitan city with all of the attending vices attached to that type of society.

Establishment of the Church

The founding of the Corinthian church was recorded by Luke in Acts (18:1–18). From Athens Paul had sent his associates Silas and Timothy back to the Macedonian churches at Philippi, Thessalonica, and Berea (Acts 17:15–16; cf. 1 Thess. 3:1–6), started earlier on this same second missionary journey. When Paul therefore left Athens for Corinth, he went alone. Cut off from his friends and supporting churches, Paul worked in tentmaking, a craft he had learned as a youth, to meet his financial needs. He found both work and lodging with a Jewish couple, Aquila and Priscilla, who practiced this same craft and who had been expelled from Rome because of the anti-Semitic decree of Caesar Claudius. Perhaps through personal conversation with Paul and his subsequent synagogue preaching, this couple came to know Jesus Christ as their Messiah and Savior. During the week, Paul worked with his hands, but every Sabbath he was in the synagogue, logically proving from the Old Testament that the promised Messiah had to suffer death and to be raised from the dead and that Jesus was indeed that promised Savior (cf. Acts 17:2–3). Many in attendance, both Jews and Gentile proselytes to the Jewish religion, were convinced and believed. When Silas and Timothy joined Paul at Corinth with a good report of the faith and stedfastness of the Macedonian Christians, Paul was constrained to press the claims of Jesus Christ more strongly upon his synagogue listeners. When this occurred, the Jews resisted and blasphemed, forcing Paul to leave the synagogue with this declaration: "Your blood be upon your own heads; I am clean; from henceforth I will go unto the Gentiles" (18:6). It was also about this time that Paul wrote First Thessalonians, based upon the content of Timothy’s report.

Paul then moved his ministry into the house of Justus which was adjacent to the Jewish synagogue. Soon after, the chief ruler of the synagogue, Crispus, along with his family, believed. From this new site, a ministry to the pagan, idolatrous Corinthians was begun with much success. The opposition must have been intense at that time because Paul received special encouragement from God. He was informed that he would not suffer bodily harm and that many would be converted through his ministry. Paul then labored for eighteen months (a.d. 50–52) both as an evangelist and as a teacher of the new congregation.

In the midst of his ministry, the Jews brought charges against Paul before Gallio, the political deputy or proconsul of Achaia. Since the accusations were religious and not political in nature, Gallio refused to arbitrate the matter. In driving the Jews from the judgment seat, Gallio declared the innocence of Paul and recognized the troublesome character of the Jews. Later the Gentile proselytes to Judaism smote Sosthenes, the chief ruler of the synagogue, who probably was a Gentile himself and a recent convert to Christianity; again, Gallio reacted negatively.

Even after this burst of persecution, Paul remained a "good while" in Corinth. With Aquila and Priscilla he then left Corinth and set sail for Antioch in Syria via Ephesus.

Time and Place

Paul left Aquila and Priscilla at Ephesus and sailed for Caesarea (Acts 18:18–22). On his arrival he visited the Jerusalem church and then returned to his home church at Antioch. After spending "some time there, he departed, and went over all the country of Galatia and Phrygia in order, strengthening all the disciples" (18:23). Thus began his third missionary journey. During this period of Paul’s absence from Ephesus, Apollos, an eloquent Jewish teacher of the doctrine of John the Baptist, came to that city and was led to a knowledge of Christ by Aquila and Priscilla. With his new faith Apollos traveled to Corinth in Achaia where he was received by the Corinthian believers and where he had a successful public ministry among the Jews (Acts 18:24–28).

While Apollos was in Corinth, Paul reached Ephesus where he would minister for the next three years (a.d. 52–55; Acts 19:1–10; 20:31). Many believe that Paul, either before or shortly after reaching Ephesus, wrote a short letter to the Corinthian church concerning the problem of fornication (1 Cor. 5:9; to be discussed, p. 208–09). About this time, because of increasing factionalism in the Corinthian church, Apollos left that city and returned to Ephesus (1 Cor. 1:12; 16:12). Some have suggested that Paul made a quick, personal visit to Corinth to arbitrate the controversy but was unsuccessful (2 Cor. 2:1; 12:14). Since Corinth was only two hundred miles west across the Aegean Sea from Ephesus, travel and communication between the two cities was easy.

The situation at Corinth continued to deteriorate. Members of the household of Chloe brought a firsthand report of the divisions within the assembly (1 Cor. 1:11). They were followed by three members of the Corinthian church (Stephanas, Fortunatus, and Achaicus) who brought Paul a financial gift (16:17). Perhaps they also carried to Paul a letter from the church in which questions were asked about various doctrinal and moral issues (7:1). Thus, through personal conversations with Apollos, the Chloe household, and the three church emissaries plus the content of the letter, Paul learned about the troubled state of the Corinthian church. Unable to leave Ephesus at that time (16:3–9), Paul did the next best thing; he wrote this letter to resolve the many problems. It was probably written near the end of his ministry at Ephesus because he had already made plans for leaving the province of Asia (16:5–7). Thus, it was composed during the fall or winter of a.d. 55 because he said that he would stay at Ephesus until Pentecost (16:8).

Who took the letter from Paul to Corinth? It is difficult to be positive here. Some speculation has centered around Timothy, but would Paul have written "Now if Timotheus comes" (16:10) if he had planned to send the letter by him? Timothy did leave Ephesus for Macedonia (Acts 19:22) probably before Paul wrote the letter. It may be that Paul was informing the Corinthian church that Timothy might visit it after his ministry in Macedonia was over. Paul did want to send Apollos back to Corinth, but he refused to go (16:12). It may be that the return of the three church members afforded Paul the chance to send the Epistle back with them (16:12; cf. 16:17–18). This latter view seems to be the most plausible.

Purposes

The purposes are very clear. First, Paul wanted to correct the problems mentioned to him in the personal reports (chs. 1–6). He rebuked the existence of church factions and tried to bring unity out of division (1:10–4:21). He introduced this section with these words:

Now I beseech you, brethren, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that ye all speak the same thing, and that there be no divisions among you; but that ye be perfectly joined together in the same mind and in the same judgment. For it hath been declared unto me of you, my brethren, by them which are of the house of Chloe, that there are contentions among you (1:10–11).

He then attempted to discipline in absentia the fornicators in their midst (5:1–13). This problem was introduced in this way: "It is reported commonly that there is fornication among you …" (5:1). Apparently, all visitors to Paul from Corinth brought news of this incest. He also tried to prevent warring church members from going to civil court against each other (6:1–8). To those who abused themselves sexually, he taught the sanctity of the believer’s body (6:9–20).

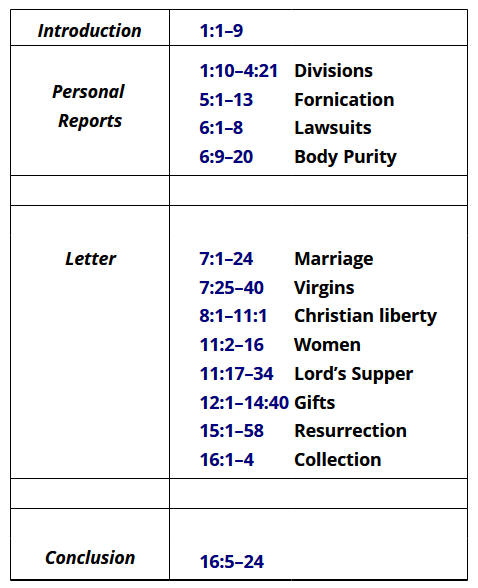

Second, the rest of the book deals with the questions raised in the letter: "Now concerning the things whereof ye wrote unto me" (7:1). With that letter probably before him, Paul logically moved from one issue to another. He marked his movement and change of subject with the key introductory word "Now" (7:1, 25; 8:1; 11:2, 17; 12:1; 15:12; 16:1). He answered their questions concerning the necessity and the problems of marriage (7:1–24), the status of virgins and widows (7:25–40), the application of Christian liberty to the eating of meat sacrificed to idols (8:1–11:1), the conduct of women in the church (11:2–16), the order of the communion service (11:17–34), the nature and use of spiritual gifts, especially those of tongues-speaking and prophecy (12:1–14:40), the necessity and nature of the resurrection body (15:1–58), and the financial collection for the poor saints at Jerusalem (16:1–4).

In addition, he wanted to announce to them his plans to visit Corinth after a tour of the Macedonian churches (16:5–18). He then closed by extending greetings to them from the Asian churches and brethren (16:19–24).

Lost Letter

In 5:9 Paul penned: "I wrote unto you in an epistle not to company with fornicators." Does this statement mean that Paul had sent a short letter to the Corinthian church before his composition of this First Epistle? If so, what happened to it and what did it contain? Was it an inspired letter or simply human correspondence? These are difficult questions with no easy answers, but there are two plausible alternatives. If Paul did write it, its theme was the relationship of Christians to fornicators. Apparently the Corinthians misunderstood Paul’s teaching and thought that they should be separate from all immoral men. However, in this section (5:1–13) Paul corrected that notion by calling for separation only from professing believers who practiced fornication or other public sins; he did not mean that they should disassociate themselves from the unsaved fornicators. If this alternative is true, the content of the original letter was summarized and incorporated into this section (5:1–13); in which case, the church is not lacking any inscripturated book or truth. This "lost letter" may also have included Paul’s plans for a return visit to Corinth (cf. 2 Cor. 1:15–16) and instructions for Corinthians’ part in the collection for the Jerusalem saints (2 Cor. 8:6, 10; 9:1–2). Even if this letter did exist and became lost, such a situation is by no means unique. After the council at Jerusalem was over, the church leaders wrote letters to the Gentile churches informing the latter of their decisions (Acts 15:20, 23–27); none of these letters has ever been found. However, the content of those letters was incorporated into Luke’s record of those proceedings. The letter that the Corinthians wrote to Paul (7:1) is also lost, but the content of that letter is revealed in the answers given by Paul (7:1–16:4).

This diagram provides a synthetic view of the entire book:

The second alternative is that 5:9 does not refer to a former letter, but to the Epistle Paul was presently writing. The verb "wrote" (egrapsa) would be regarded as an epistolary usage of the Greek aorist tense (same word occurs in 5:11, translated "have written"). This means that Paul looked at his present discussion of fornication from the viewpoint of the Corinthian readers. At the time they would read it, his writing of it would be in the past. This is why he used a past verbal tense ("wrote") rather than the present ("write"). It is difficult to be positive here, but either alternative is an acceptable evangelical option.

Some liberals, who accept the thesis of a lost letter, actually believe that parts of this lost letter can be seen in both Epistles (1 Cor. 6:12–20; 2 Cor. 6:14–7:1). However, this theory rests merely upon subjective speculation, not upon objective, external or textual evidence for its support. The first passage deals with the believer’s relationship to his own body, and the second warns against involvement with unbelievers rather than against involvement with professing believers who are guilty of sexual sins. They treat different subjects than that in the passage under discussion (5:1–13).

Outline

Salutation (1:1–9)

I. Reply to Personal Report (1:10–6:20)

A. Correction of church divisions (1:10–4:21)

1. By a true concept of salvation (1:10–25)

2. By an honest evaluation of their past (1:26–31)

3. By an understanding of the ministry of the Holy Spirit (2:1–13)

4. By a knowledge of carnality and spirituality (2:14–3:3)

5. By an appreciation of the total ministry (3:4–4:21)

B. Discipline of fornication (5:1–13)

C. Criticism of lawsuits (6:1–8)

D. Criticism of sexual abuse (6:9–20)

II. Reply to Questions in Their Letter (7:1–16:4)

A. Concerning marriage (7:1–24)

B. Concerning virgins (7:25–40)

C. Concerning things sacrificed to idols (8:1–11:1)

1. The problem (8:1–13)

2. The rights of ministers (9:1–27)

3. The lessons of the past (10:1–22)

4. The principles of liberty (10:23–11:1)

D. Concerning problems of worship (11:2–34)

1. The veiling of women (11:2–16)

2. The Lord’s Supper (11:17–34)

E. Concerning spiritual gifts (12:1–14:40)

1. List of gifts (12:1–11)

2. Need of gifts (12:12–31)

3. Exercise of gifts (13:1–13)

4. Contrast between prophecy and tongues (14:1–40)

F. Concerning the resurrection (15:1–58)

1. Part of the gospel (15:1–11)

2. Necessity of Christ’s resurrection (15:12–34)

3. Nature of the resurrection body (15:35–50)

4. Time of the resurrection (15:51–58)

G. Concerning the collection (16:1–4)

Closing Remarks and Greetings (16:5–24)

Survey

1:1–9

Although the Corinthians were saturated with spiritual problems, Paul addressed them as sanctified ones or saints. Their position in Christ had not changed even though their practice needed correction. They possessed a unity in Him that should have been manifested in their local church life but was not. He then thanked God that they had been endowed with all the spiritual gifts (cf. chs. 12–14) by the grace of Christ and that they expected His return. Before correction and criticism, he gave commendation.

1:10–17

On the basis of their same spiritual standing and hope, Paul appealed to them to strive for unity. The house of Chloe had informed him that there were divisions within the church, caused not by heretical doctrine but through the exaltation of human leaders: "Now this I say, that every one of you saith, I am of Paul; and I of Apollos; and I of Cephas; and I of Christ" (1:12). This does not mean that the Corinthians were divided into four groups following these four mentioned individuals. Later Paul wrote: "And these things, brethren, I have in a figure transferred to myself and to Apollos for your sakes …" (4:6). Paul chose not to identify the Corinthian leaders by name; rather he transferred the allegiance given to them to Christ, Peter, Apollos, and himself. In expressing thanks that he had not baptized more Corinthian converts, he did not deprecate the ordinance of water baptism, but rather he did not want men to exalt him for that personal involvement in their lives.

Fountainhead of Peirene at Corinth.

1:18–25

When men exalt other men, the former invariably exalt what the others know and/or their ability to communicate what they know. Paul tried to show that the wisdom of words, of the wise, and of the world was not responsible for their salvation, but that the gospel message of Christ’s crucifixion saved them. To unsaved Jews who wanted a sign-miracle, this was a stumblingblock; to Greeks who wanted a philosophical presentation, this was foolishness; but to saved Jews and Gentiles, it manifested the power and wisdom of God.

1:26–31

Paul also reminded them that God did not save them because of who they were. He delighted to make "somebodies" out of "nobodies" so that the recipients of His creative grace would glory in Him, not in their station of life, either past, present, or future. To confound the wise, mighty, and noble, He chose the foolish, weak, base, and despised, and the things which are not. All spiritual possessions (wisdom, righteousness, sanctification, and redemption) have been made or imputed to us because of our position in Christ, not because of our human status.

2:1–8

Paul then reminded them of the methods employed by him when he evangelized them. His presentation was not marked by overwhelming human oratory or philosophical logic, but by human insufficiency and total dependence upon the Holy Spirit. Thus, their conversion by faith did not stand "in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God." In no way could they exalt the ability of Paul as the reason they accepted Christ.

2:9–13

Paul further explained that spiritual truth is only taught by the Holy Spirit to hearts that are open to Him. Mere human wisdom could not anticipate, let alone understand, divine truth. This truth must be revealed, and God has revealed it through the oral preaching and the inscripturated books of the apostles and prophets. This revelation was done and supervised by His Spirit; therefore, the believer has received the indwelling, teaching presence of the Holy Spirit in order to "know the things that are freely given to us of God." Paul was effective among the Corinthians because he spoke "not in the words which man’s wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Spirit teacheth." This passage therefore teaches that the divine works of revelation (2:10), inspiration (2:13), and illumination (2:12) are accomplished by the Holy Spirit through men; thus He, not the human instrument, should be praised.

2:14–3:3

Paul then divided all men into three categories: natural, spiritual, and carnal. The natural man is the unsaved man who cannot perceive spiritual truth because he has no inner capacity to receive it; he is void of the indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit. The spiritual man is not only saved, but is yielded to the teaching ministry of this indwelling Spirit; thus he is in a position to receive all spiritual truth in which the Spirit chooses to instruct him. The carnal man is also saved, but he is not yielded to the Spirit; thus, because he is not in a position to be taught by Him, he will think and behave like an unsaved man. The church divisions at Corinth were no doubt caused by the presence of all three classes of men, especially the carnal Christians, within their ranks.

3:4–7

Following human leaders is an expression of carnality. Such actions fail to realize the real purpose of the ministry: "Who then is Paul, and who is Apollos, but ministers by whom ye believed, even as the Lord gave to every man?" (3:5). Ministers should not compete with each other, but they should complement each other. If anyone is saved and/or edified, it is because "God gave the increase"; no man can take the credit for that.

3:8–4:21

Paul reinforced this concept by equating the work of the ministry with the construction of a building. As the pioneer evangelist, he laid the foundation of the Corinthian church; those who ministered after him built upon that foundation. At the judgment seat of Christ, they will receive rewards or suffer the loss of rewards based upon the quality of their effort. All ministers have been given for the mutual benefit of all believers by Christ to whom they are ultimately responsible; therefore, Christians should not "think of men above that which is written, that no one of you be puffed up for one against another" (4:6). Paul then argued that whatever abilities men possess they have them because God gave them in the first place. How then can anyone boast of himself or another? With sanctified sarcasm, Paul tried to point out their erroneous thinking by contrasting their life-styles with the life-style of the apostles. He then warned them as a father would his son about resolving their differences before he visited them.

5:1–13

The second major problem brought to Paul via oral report centered in a church member guilty of a sexual sin not even practiced by unsaved Gentiles. He apparently was having a known affair with his stepmother. Instead of disciplining the fornicator, the church tolerated his presence in its midst. Paul exercised his apostolic authority and charged them to excommunicate the member. Deliverance to Satan of an erring brother was probably an extreme apostolic measure in harmony with divine chastisement (cf. 1 Tim. 1:20). Paul equated this type of open, unrepentant sin with leaven that would spread to other church members if not purged. He cautioned them against refraining from association with unsaved, wicked people because the latter need the witness of the former; however, he charged that believers should not keep company with professing Christians who are known for such wicked practices. It is the responsibility of the local church to judge its own members; God will judge the unsaved.

6:1–8

The divisions within the church had caused such deterioration that Christians were taking other believers before pagan civil magistrates to settle their differences. Since believers will judge the world and angels during the millennial kingdom and/or at the great white throne judgment, Paul argued that they should be able to solve their problems within the local church. He also suggested that it would be better to take wrong and to be defrauded than to expose the testimony of Christ and the church to public ridicule.

6:9–20

After positing that the unrighteous would not inherit the kingdom of God, Paul listed those men whose life-styles would prevent them from gaining the kingdom. However, God can take men with such sinful practice, as He did with some of the Corinthians, and transform them into saints with an acceptable spiritual position (washed, sanctified, justified). Many of the Corinthians, though, were abusing their bodies with improper diet or sexual relationships. Paul informed them that their bodies were now the temples of the Holy Spirit, that such sins were against their bodies, that they were now owned by God by right of spiritual redemption, and that they should glorify God with both their bodies and spirits.

7:1–9

Paul ended his reaction to the four problems brought to him orally (1:10–6:20) and began to answer the questions found in their letter to him (7:1). The first issue actually is related to the believer’s understanding of the sanctity of his own body (6:9–20). Paul charged that premarital sexual affairs were wrong, that marriage was recommended in order to avoid sexual impurity, and that husbands and wives should understand their sexual responsibility to each other. His counsel to the unmarried and widows to remain single was given by permission, not of commandment. That meant that he did not speak as an apostle with divine authority, but rather as a spiritual brother giving his opinion.

7:10–24

The next section was addressed to married people. In it Paul set forth principles to govern separation, divorce, and reconciliation. Paul wanted the home to be maintained at all costs for the future salvation of the unsaved members of the household. Some have seen a difference between divine directives and human advice in two of Paul’s admissions: "I command, yet not I, but the Lord" (7:10) and "But to the rest speak I, not the Lord" (7:12). The first meant that Paul voiced exactly what Christ had said on the subject (cf. Matt. 19:3–12), whereas the second meant that Christ had not orally spoken on the subject, but that Paul was speaking as a divinely authenticated apostle. He concluded that men should abide in that calling (slave, free, uncircumcision, etc.) wherein they were saved (7:20, 24). This principle could perhaps apply to the status of married life (a believer married to an unsaved partner).

7:25–40

Concerning virgins, Paul had not received any oral or written revelation from Christ; here he gave his judgment or advice after much thought on the subject (7:25; cf. 7:40). Because of the atmosphere of persecution at Corinth (7:26, 29), Paul recommended that the single remain single and that the widows remain unmarried. He further stated that the unmarried would be able to give more time and effort to the things of the Lord than the married person who also has obligations to his partner. He did recognize the acceptable option of marriage for the virgin and advised the widow, if she decided to remarry, to marry only a believer.

8:1–13

The problem of eating meat taken from animals sacrificed to idols also existed at Corinth (cf. Rom. 14). Perhaps the divisions in this church were caused partially by a difference of opinion in this area. In this controversial area of Christian liberty, Paul stated that men should be motivated by love, not by knowledge. Some believers knew that idols and gods did not actually exist because there is only one living God in the world; therefore, they could eat such meat with clear consciences. Other Christians still admitted the reality of pagan idolatry and could not eat such food with a pure conscience. The mere eating or noneating was not the real spiritual issue; rather, Paul cautioned against offending the brother with a misuse of one’s liberty. To eat with full knowledge that a brother is being spiritually hurt is to sin against Christ. Paul concluded that under such circumstances he would not eat.

9:1–27

As an illustration of not using one’s rights, Paul referred to his own apostolic prerogative to be supported financially by the gifts of God’s people. The Corinthians knew that Paul had been commissioned by the risen Christ to be an apostle through his spiritual ministry in their midst. Paul stated that both Barnabas and he had the same power to eat, to drink, to lead about a wife, and to stop manual labor as the other apostles. Both human logic and the Old Testament agreed that a minister should be supported materially; however, Paul chose not to exercise that right. He elected to work with his own hands as a tentmaker in Corinth so that none could accuse him of being in the ministry for what he could get out of it. Paul’s motivation was clear: "For though I be free from all men, yet have I made myself servant unto all, that I might gain the more" (9:19). Paul wanted to win men to Christ, and to do that he adjusted his life-style and approach so that he would not offend the person he was trying to win. He also made sure that he had complete control of the desires of his body so that he would not forfeit the rewards of faithful service.

10:1–11:1

Paul concluded this section by referring to Old Testament examples of those who were severely chastised by God for sins of idolatry, fornication, tempting, murmuring, and pride. Apparently those who believed in the nonexistence of idols thought that they not only could eat meat sacrificed to idols but also participate in some of the pagan feasts. They had taken their liberty to an illogical, sinful extreme. Paul warned against such fellowship with demons and saw in it a provocation of God. He advised that expediency and edification should dictate whether one should exercise his liberty in all situations. In all such areas believers should seek to glorify God and to give no offense to either the unsaved or the saved. Liberty should not be used selfishly but benevolently.

11:2–16

Paul now moved from questions about personal life (7:1–11:1) to questions about the public worship service (11:2–14:40). The first dealt with the place of the Christian woman within the church. He introduced this section by outlining the order of authoritative headship within the divine plan: God, Christ, man, and woman. He argued that a man would dishonor Christ if he prayed or prophesied with his physical head covered and that a woman would dishonor her husband if she did these things with her head uncovered. The covering of the woman’s head was a sign in that culture of the woman’s subjection to her husband. The Christian woman probably reasoned that if she and her husband were spiritual equals in Christ, she need not wear the mark of subordination in spiritual activities within the church. However, the family headship of the man over the woman established at creation was not to be violated within the church. Just as there is an equality of spiritual essence within the three Persons of the divine Godhead, so there is also an order for the execution of the divine will. The same principle applies to the husband-wife relationship; there is an equality in Christ, but there is an order within the family and the church to do God’s will properly.

11:17–34

The carnality visibly seen in the church divisions had even affected the public observance of the ordinance of the Lord’s Supper. In the eating of the love feast that preceded the ordinance, those who had much food did not share with those who had none; in fact, some even became drunk while others hungered. Paul then outlined how the supper should be received by the believer. The eating of the bread and the drinking of the wine were to be done in remembrance of Christ’s person and redemptive work and in anticipation of His return. Paul warned that their violations of this holy ordinance had brought physical sickness and premature death to many of the Corinthian church. He commanded that self-examination should precede the observance of the ordinance; if a believer does not confess and repent of his sin, then God must judge or chastise him in this life.

12:1–31

Another problem concerned ignorance over the nature and purpose of spiritual gifts. Although there were more (Rom. 12:6–8; Eph. 4:11), Paul listed only nine: wisdom, knowledge, faith, healing, miracles, prophecy, discerning of spirits, tongues-speaking, and interpretation of tongues. Every believer received at least one of these gifts (12:7). These gifts were not chosen by men, but were sovereignly given (12:11, 18). By using the analogy of the one body with its many members, Paul demonstrated that believers should not all expect to have the same gift, that one gift should not be exalted above another, that all gifts should be used to complement the others, and that all should work together for the spiritual growth and health of the body, a symbol of the true church, composed of saved Jews and Gentiles and entered by the baptism in the Holy Spirit (12:12–31). These spiritual gifts then (pneumatika or charismata) were abilities given to the Christian out of the grace of God through the Spirit to be used for the spiritual profit of the entire church.

13:1–13

Paul then argued that unless the gifts were exercised in the attitude of love toward both God and Christian brethren, they were of no profit to anyone (13:1–3). In describing the qualities of love (13:4–8a), he repudiated their divisive spirit. Their exaltation of certain gifts no doubt contributed to the contentions among them. Paul predicted that the gifts of prophecy and knowledge would be rendered inoperative by the coming of "that which is perfect" and that tongues would cease even before that event. Most evangelicals are divided over the meaning of "that which is perfect." It is seen as referring either to the completion of the canon (or written revelation) or to the second coming of Christ. If the former, then these gifts were definitely temporary and served only the needs of the apostolic church. If the latter, then the gifts of prophecy and knowledge would be permanently operative until Christ’s return, whereas the gift of tongues would cease at some time before the event. Paul argued that the quality of love would go into eternity; therefore, it should be emphasized over the use of gifts.

14:1–40

The spectacular gift of tongues-speaking was at the center of the gift controversy. It apparently was misused and exalted out of proportion. Paul set forth several regulations to control the use of the gift in the public service of the church. Tongues had to be interpreted in order to have any profit for the entire congregation. Edification of the group was the main goal of any gift (14:3, 4, 5, 6, 12, 17, 26). Speaking in tongues was designed specifically as a sign to unbelieving Jews (14:21–22). There could be no more than three tongues-speakers in any service and they were to speak one at a time (14:27). A fourth person was to give the interpretation for all three tongues-speakers (14:27). If no interpreter were present, the tongues-speaker was to remain silent (14:28). Peace and order were to characterize the services (14:33, 40). Possibly the gift of tongues was not given to women (14:34), but this verse may refer to the interruption of the prophets by women questioners. Paul commended to them the gift of prophecy, but he warned them not to forbid tongues-speaking as long as the gift was sovereignly given.

15:1–58

The church was also involved in a doctrinal controversy over the resurrection. Paul stated that the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ was an integral part of the gospel message and that no one could be saved apart from faith in a crucified, resurrected Christ (15:1–4). He alleged that Christ’s resurrection was both historically and scientifically verified through His many postresurrection appearances (15:5–11). Some at Corinth apparently thought they could believe in the resurrection of Christ without believing in a future, general resurrection of the dead. Paul argued that Christ could not be separated from the stream of humanity. If there is no future resurrection, then Christ was not raised in the past; if that is true, then Paul saw himself as a false witness and the Corinthians as those still in their sins (15:12–19). However, Christ did rise from the dead, and that reality assures all men of a future resurrection (15:20–34). He stated that the resurrection body is related to the natural body, but not identical with it, that it is a spiritual, incorruptible, glorified body, and that it is of the same essence as Christ’s resurrection body (15:35–50). Paul then disclosed the mystery that not all believers would die before the coming of Christ, but that some would be alive when He returns. When He does return, the dead will receive a new body not subject to disease (incorruptible) or death (immortal) through resurrection, and the living will receive a new body through translation (15:51–58).

16:1–4

The final question dealt with the collection for the poor Jewish saints at Jerusalem. Paul advised the Corinthians to continue taking an offering every week so that he would not need to do it after he arrived at Corinth. He also suggested that some of their members could accompany him on his relief trip to Jerusalem.

16:5–24

Paul then closed the Epistle by announcing his travel plans, by informing them about Timothy and Apollos, by commending their three church ambassadors, and by extending greetings to them.