15

COLOSSIANS

Writer

All evidence definitely points to Paul as the author. He named himself as Paul three times (1:1, 23; 4:18). He identified himself both as an apostle and a minister (1:1, 23, 25). He ended the Epistle with his typical handwritten salutation (4:18; cf. 2 Thess. 3:17). His associates at the writing of Colossians (1:1; 4:9–14) are also mentioned in Philemon (vv. 1, 10, 23–24): Timothy, Onesimus, Aristarchus, Mark, Epaphras, Luke, and Demas. In both of these books, he addressed Archippus (Col. 4:17; Philem. v. 2). These features argue for a single author of both books at the same time from the same place.

Some have argued against Pauline authorship by stating that the style and vocabulary in this book are different from the style and vocabulary in his other Epistles. The nature of the subject matter often determines the literary style and the choice of words, however. Actually, there is a great similarity of content between Ephesians and Colossians. Others feel that the nature of the heresy was too advanced for the sixth and seventh decades of the first century and that it reflects a second-century error; however, the book refutes an incipient Gnosticism, not a mature expression. Some critics believe that the theological concepts of Christ’s person and work are also advanced, but His sovereign deity is expressed elsewhere by Paul (cf. Phil. 2:5–11).

Early church tradition supported the Pauline authorship of Colossians. The Muratorian Canon and these historical Fathers recognized it as canonical: Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Origen, and Marcion.

City of Colosse

The city was situated on a rocky ridge overlooking the valley of the Lycus River that ran through this mountainous district. It was located about one hundred miles east of Ephesus and about twelve miles north of Laodicea. In the fifth century b.c. during the Persian wars, it was a very important city, but as her companion cities Laodicea and Hierapolis grew, she declined. In New Testament times she ranked third behind the other two. However, the city did retain some mercantile value because it was one of the stops on the trade route to the east and because glossy black wool was provided through the sheep industry in the adjoining hills. The city was destroyed by an earthquake during the reign of Nero, but it was quickly rebuilt. Today, the ancient site lies in ruins with a modern town, Chronas, located nearby.

Establishment of the Church

The evangelization of Colosse is not specifically mentioned in the Book of Acts. During Paul’s three years of ministry in Ephesus, Luke recorded "that all they which dwelt in Asia heard the word of the Lord Jesus, both Jews and Greeks" (Acts 19:10). Most scholars feel that it was at this time the church at Colosse was founded. Paul, though, probably did not go to Colosse himself. He wrote: "For I would that ye knew what great conflict I have for you, and for them at Laodicea, and for as many as have not seen my face in the flesh" (2:1). This verse suggests that both the Laodicean and the Colossian churches had not experienced his direct, personal ministry. How then were the churches started? There are two strong alternatives. The first is that one of Paul’s associates, possibly Timothy, went into the region of Laodicea and Colosse during the apostle’s stay at Ephesus. Perhaps this is why the name of Timothy is included in the introductory greeting (1:1). The second is that residents of Laodicea and Colosse, perhaps Epaphras (1:7–8; 4:12–13), Nymphas (4:15) and/or Philemon (Philem. vv. 1–2), journeyed to Ephesus, were saved directly through Paul’s ministry, returned to their hometowns, and started churches there. Paul had led Philemon to Christ (Philem. v. 19) and since Paul knew several by name in Colosse and Laodicea (Epaphras, Nymphas, Philemon, Apphia, and Archippus), this view looms as a strong possibility. The converts of these initial converts had never had the privilege of seeing Paul, and yet they looked to him for apostolic direction. In a sense, he was their "spiritual grandfather." This is why Paul’s knowledge of their spiritual condition was secondhand (1:4, 8).

The membership was composed largely, if not exclusively, of Gentiles. Paul identified them as "being dead in your sins and the uncircumcision of your flesh" (2:13; cf. Eph. 2:1). The title "uncircumcision" is a designation for Gentiles (cf. Rom. 2:24–27; Eph. 2:11). It is hermeneutically possible that the phrases "among the Gentiles" and "in you" were meant to be synonymous. The phrase, "And you, that were sometime alienated and enemies in your mind" (1:21), sounds like Paul’s description of lost Gentiles elsewhere (Eph. 2:11–12; 4:17–18).

Nature of the Heresy

The false teaching at Colosse consisted of a mixture or merger of Jewish legalism, Greek or incipient Gnostic philosophy, and possibly Oriental mysticism. Because of these diverse elements, some have thought that Paul was dealing with two or three different groups of false teachers; however, the characteristics are so interwoven throughout the book as to suggest one group of heretics with multiple errors in their teaching. Were these teachers Jewish or Gentile? It is difficult to say with certainty; neither answer affects the content of the heresy. Thus it is safe to identify the false teaching as either Judaistic Gnosticism or Gnostic Judaism. Many Jews lived in that area because their ancestors were forced to migrate there under the Seleucidae ruler, Antiochus III. The descendants eventually strayed away from orthodox Judaism and sucumbed to the influence of Greek philosophy. The heresy at Colosse did have a strong Jewish ritualistic character, whereas second-century Gnosticism manifested more the philosophical element. It is also difficult to determine whether these heretics were within the church membership or attacked the church from without. Paul warned against both sources (Acts 20:29–30). Since the church was young and did have some adequate leadership, it would seem that the heresy came as an outside threat.

What were its teachings? It taught that spiritual knowledge was available only to those with superior intellects, thus creating a spiritual caste system. Faith was treated with contempt; advanced Gnosticism even taught that salvation was received by knowledge. Adherents believed that they could understand divine mysteries totally unknown and unavailable to the typical Christian.

Another influence of Greek philosophy was in its teaching that all matter was innately evil and that the soul or mind was intrinsically good. This logically led to a denial of the creation of the material world by God and to a denial of the incarnation of Jesus Christ. The latter involved a repudiation of His humanity, His physical death, and His physical resurrection.

To explain the existence of the material world, the heresy taught that a series of angelic emanations created it. According to them, God created an angel who created another angel who in turn created another angel ad infinitum. The last angel in this series then created the world. This angelic cosmogony thus denied the direct creation and supervision of the world by God. This conviction resulted in some practical theological error. It stressed the transcendance of God to the exclusion of His immanence. Since God did not create the world in the past, He does not work in the world in the present. This would rule out the value of prayer or the possibility of miracles. It led to a false worship of angels. If the world resulted from angelic emanations, then the person in the world had to work his way back to God through this series. Thus he would have to know who those angels were and how many there were in order to give each his proper respect.

Christ was reduced by most Gnostics into a creature, perhaps the highest being that God created. This was an attack upon the Trinity and upon the eternal, sovereign deity of Jesus Christ.

In daily living, the heresy led to asceticism and legalism. If matter is evil, then the body is evil. The heresy taught that to destroy the desires of the body to satisfy the needs of the soul, a rigid code of behavior, including circumcision, dietary laws, and observances of feasts, had to be followed.

The dangers of the heresy were quite obvious to Paul. His refutation of them will be seen in the survey.

Time and Place

During Paul’s absence from Asia, this Judaistic-Gnostic heresy began to infiltrate the area. The leaders of the Colossian church were apparently unable to cope with it so they sent Epaphras to Rome to consult with Paul. Quite possibly, Epaphras was the founder and pastor of the church; when he left, Archippus assumed the pastoral responsibility (1:7; 4:17). Epaphras informed Paul of the Colossians’ faith (1:4–5), their love for Paul (1:8), and the heretical threat. Unable to go to Colosse because of his imprisonment, Paul penned this Epistle and sent it to the church through Tychicus and Onesimus (4:7–9). For some unknown reason Epaphras was imprisoned along with Paul by the Roman government (Philem. v. 23). Since Epaphras could not return to Colosse at this time to correct the situation with the apostolic authority of the Epistle, the task was assigned to Tychicus. However, Paul assured the church that Epaphras was laboring "fervently for you in prayers, that ye may stand perfect and complete in all the will of God" (4:12). Thus, within eight years of the establishment of the church, Paul had to write to this young, immature, threatened church to warn them against the errors of the heresy (2:8, 16, 20).

Purposes

Paul wrote, therefore, to express his prayerful interest in the spiritual development of the Colossian believers (1:1–12), to set forth the sovereign headship of Jesus Christ over creation and the Church (1:13–29), to warn them against the moral and doctrinal errors of the heresy (2:1–23), to exhort them to a life of holiness (3:1–4:6), to explain the mission of Tychicus and Onesimus (4:7–9), to send greetings from his associates (4:10–15), and to command the exchange of correspondence with the Laodicean church (4:16–18).

Distinctive Features

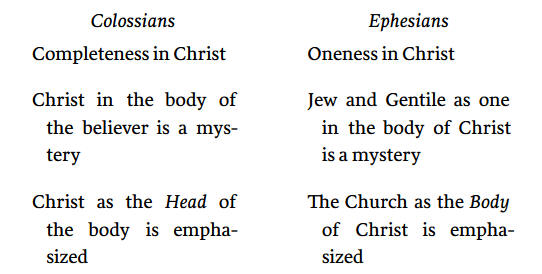

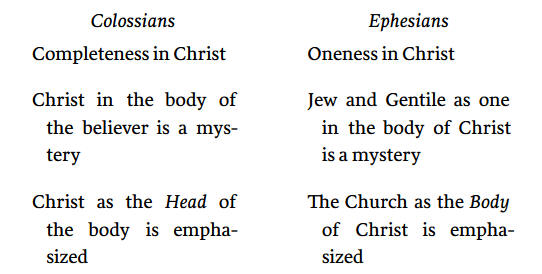

The close resemblance to Ephesians both in content and vocabulary must again be mentioned. So much of Colossians is repeated in Ephesians that the two books must have been written at the same time from the same place with similar themes. Here are some related contrasts:

This book contains a classic passage on the preeminence of Jesus Christ (1:14–22). It actually develops grammatically as a relative clause ("in whom," en ho) within the apostle’s prayer (1:9–14). The listed descriptive titles of Him are unique: the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature, the head of the body, the beginning, and the firstborn from the dead. His role as creator of the universe is explained through four prepositional phrases: sphere of creation (literally, "in him," en auto; 1:16); agent of creation ("by him," di autou; 1:16); goal of creation ("for him," eis auton; 1:16); and prior to creation ("before all things," pro panton; 1:17). Paul also called Him the sustainer of creation ("by him all things consist"). Both in the natural and in the spiritual creations, Christ is sovereign and should have the preeminence.

Colossians contains the most severe warning against unguided human intellect or non-Biblical philosophy: "Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ" (2:8). The Greek word for "philosophy" (philosophia) means "love of wisdom." In Christ are "hid all the treasures of wisdom [sophias] and knowledge" (2:3); therefore, a genuine love for wisdom should lead to a perfect love for Christ. However, there are many systems that go under the guide of "philosophy" that are really governed by human or world standards, by humanism or antisupernaturalism, rather than by divine revelation centered in the person of Christ. Christians need to distinguish between true and false philosophies.

Outline

Introduction (1:1–8)

I. The Preeminence of Christ (1:9–29)

A. The prayer of Paul (1:9–14)

B. The person of Christ (1:15–20)

C. The work of Christ (1:21–29)

II. The Warning Against the Heresy (2:1–23)

A. The concern of Paul (2:1–5)

B. The safeguard against heresy (2:6–15)

C. The description of the heresy (2:16–23)

III. The Practice of True Christian Living (3:1–4:6)

A. Its foundation (3:1–4)

B. Its principles (3:5–17)

C. Its applications (3:18–4:6)

1. Wives (3:18)

2. Husbands (3:19)

3. Children (3:20)

4. Parents (3:21)

5. Servants (3:22–25)

6. Masters (4:1)

7. Church members (4:2–6)

Conclusion (4:7–18)

Survey

1:1–8

Paul’s refutation of the heresy will be seen through a positive presentation of the truth rather than through a repudiation of it point by point. He initially declared that his apostleship came from the will of God and that the Colossian believers had received grace and peace from both the Father and the Son, thus denying the allegation that God had no direct contact with mortal man. He then gave thanks for their faith, love, and hope; but note the obvious omission of wisdom, the very thing the heretics exalted. These three spiritual realities were produced by hearing "the word of truth of the gospel" (1:5) and "the grace of God in truth" (1:6), not through Gnostic mysteries.

1:9–13

Paul then prayed that the believers "might be filled with the knowledge of his will in all wisdom and spiritual understanding" (1:9). His use of the very terms employed by the heretics probably startled his readers; however, Paul demonstrated that such knowledge was available to all of the believers, not just to a privileged few, and that this knowledge was not an end in itself but should issue in a worthy walk before Christ. The fourfold description of this walk was marked by the phrases introduced by these four participles: being fruitful, increasing, being strengthened, and giving thanks. The Father deserved thanks for three works: He "made us meet to be partakers of the inheritance of the saints in light"; He "delivered us from the power of darkness"; and He "translated us into the kingdom of his dear Son."

1:14–19

After mentioning the Son, Paul expounded the nature of the person of Jesus Christ and His relationships both to the natural, material creation and to the supernatural, spiritual creation. As the image of the invisible God, He had revealed God to man; all that God is, He is (John 1:18; 10:30; 14:9). He was the firstborn or sovereign of the material world because He made and sustains it. Through His death and resurrection He became the sovereign head of His spiritual creation, the Church. Christ was personally responsible for both material and spiritual realities, not a series of angelic emanations. Both in the natural world and in the Church, He (not angels) deserves the preeminence, because the fullness of deity is within Him.

1:20–23

Paul then emphasized that peace and reconciliation could be secured only through "the blood of his cross" and "the body of his flesh through death." These are material entities, things that the heretics claimed to be innately evil. Paul also placed their past spiritual alienation and enmity in their minds, the immaterial part of man that the heretics exalted and claimed to be intrinsically good. Paul’s teaching thus was diametrically opposed to theirs. He warned that yielding to the heresy could result in the loss of future reward and could possibly manifest the fact that they were not really saved in the first place.

1:24–2:3

Paul then claimed that he was a minister of the dispensation of God which had been given to him and that he could reveal a spiritual mystery unknown to past generations. The mystery was that Christ, in His spiritual presence, was indwelling every believer. Based on that fact, Paul warned, and taught, and desired to present "every man" perfect to Christ. Thus the charge of the heretics that perfection was available to only a select few was wrong. Since all of the treasures of divine wisdom are in Christ (2:3) and Christ is in every believer (1:27), then every believer has access to the divine reservoir of spiritual truth.

2:4–8

Paul then warned the readers against the enticing words and the human, worldly philosophy and vain deceit of the heretics. He wanted them to remain steadfast, to walk by faith, to be established doctrinally, and to be thankful for what God had provided in Christ.

2:9–15

Paul then argued that the believer’s position in Christ released him from ritualistic, legalistic obligations so imposed by the Judaistic Gnostics. Every Christian is complete or positionally perfect in Christ; each has experienced spiritual circumcision; each died, was buried, and rose again in Christ as pictured by baptism; each has been quickened; and every one has been judicially forgiven of all his trespasses. Christ’s death blotted out and removed "the handwriting of ordinances" (the law with its regulations and curses); His resurrection and ascension have set believers free from them.

2:16–23

Based on Christ’s accomplishments, Paul issued two imperatives. First, "Let no man therefore judge you.…" The legalistic regulations of diet and feast observances in the Old Testament were designed as shadows or types to point to the substance or the antitype, namely Christ. Embrace the body, not the shadow, was Paul’s cry. Second, "Let no man beguile you.…" Paul claimed that the worship of angels stemmed from a hypocritical humility, ignorant speculation, carnal pride, and a devaluation of Christ’s sovereign headship. Paul then asked a rhetorical question of his readers: How could they subject themselves to ascetic prohibitions when they were dead to them through Christ?

3:1–17

The alternative to a legalistic, ascetic life is a Christ- and heaven-centered mind and heart. He explained the correct principles of Christian living through a series of nine imperatives: Mortify (3:5); put off (3:8); lie not one to another (3:9); put on (3:12); put on love (3:14); let the peace of God rule (3:15); be ye thankful (3:15); let the word of Christ dwell in you (3:16); and do all in the name of the Lord Jesus (3:17). These commands are based on the facts that their present practice should not manifest past experiences (3:6–7), that they positionally have put off the old man and have put on the new (3:9–10), that they are the elect of God (3:12), that they have been forgiven (3:13), that they have been called into one body (3:15), and that they should be thankful for all that God had done for them (3:17).

3:18–4:6

Paul then gave specific illustrations as to how these general principles could be put into practice in domestic, family situations. He used direct address and pointed imperatives: Wives, obey; Husbands, love and be not bitter; Children, obey; Fathers or Parents, provoke not; Servants, obey and do heartily; and Masters, give. He concluded the instructional section of this Epistle with four commands for all of the church members: continue in prayer; watch in prayer with thanksgiving; walk in wisdom; and let your speech be always with grace. He requested their prayer for him and his ministry in prison.

4:7–18

Finally, he informed them that Tychicus would give them an oral report of his personal state and that Tychicus was his authoritative representative to deal with the heresy and to comfort them. He also mentioned that Onesimus, a native Colossian, would assist Tychicus. He then sent greetings to them from Aristarchus, Marcus, and Jesus Justus, three Jewish co-workers (4:10–11). He continued with more greetings from Epaphras, Luke, and Demas (4:12–14). Paul notified them that he wanted to be remembered to the believers at Laodicea, to Nymphas, and to the latter’s house-church (possibly in Hierapolis). He charged them to exchange their Epistle with the one from Laodicea (possibly Ephesians). He asked the church to influence Archippus to fulfill his ministry and concluded with his typical salutation.