2

INTRODUCTION

Title

Christians are men and women of the Book. The Muslim people have the Koran, the Hindus have the Rig-Veda, but Christians base their faith and practice upon the Bible. But why is this group of sixty-six books called the Bible? Why not some other name? The title is based upon the word biblos, the name of the papyrus or byblos reed used in ancient times for making scrolls or writing paper. In fact, the ancient Phoenician city of Byblos was so named because it was the commercial center for the manufacture and shipping of this precious writing material. The magnificent ruins of Byblos can still be visited in modern Lebanon today. Daniel regarded the prophecy of Jeremiah as one of the books (

ta biblia in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament; Dan. 9:2) by which he understood the length of the Babylonian captivity. From his Roman prison Paul charged Timothy to bring "the books, especially the parchments" (2 Tim. 4:13). Both of these references show the use of ta biblia for some of the Old and New Testament books. Very early in church history Christians called the Scriptures "The Books." The dominance of the Roman church fostered the use of the Latin word biblia which is the same in the French language. By the thirteenth century, The Books (plural) came to be known as The Book (singular). Our English word "Bible" is, then, based upon the Latin and French with an Anglicized ending. This title shows the basic authority and unity of all of the books within the two testaments. Christians do not regard the New Testament as a second Bible; they follow one book, with two major divisions of equal value and authority.Jesus Christ referred to the Old Testament books as the "scriptures" (Matt. 21:42) or the "scripture" (John 10:35), using both the singular and plural designations. The word "scripture" is the translation of the Greek word graphe, which basically means "a writing." Christ regarded the written, prophetic word to be authoritative and divinely inspired. New Testament writers did likewise (Acts 18:24; Rom. 15:4). Paul even called them "the holy scriptures" (2 Tim. 3:15; Rom. 1:2), and "the oracles of God" (Rom. 3:2). Now, the question is, Were the New Testament books also so entitled? When Paul claimed that all scripture was divinely inspired or God-breathed (2 Tim. 3:16), over fifteen of the New Testament books had already been written. Would not these books also be profitable for Timothy’s spiritual growth? It would certainly appear so. Earlier, in proving that elders should be supported financially, Paul quoted from two books (Deut. 25:4; Luke 10:7) and referred to them under the singular title, "the scripture" (1 Tim. 5:18). Paul thus regarded Luke’s Gospel as the authoritative equal of Moses’ fifth book; he also saw the two testaments as a single unit. Peter cautioned against twisting the Epistles of Paul "… as they do also the other scriptures, unto their own destruction" (2 Peter 3:15–16). Note that Peter knew of Paul’s letters and of their collection into a single group. His use of "other" is very critical here; he must have valued Paul’s Epistles as scripture also. For example, a person may say, "I read Life, Time, and other magazines." This is a proper use of "other" because Life and Time are magazines. Therefore, another fitting title for the New Testament is that of "Scripture."

The second half of our English Bible is more commonly called the New Testament. Tertullian, an early Church Father (c. 200), first employed the Latin Novum Testamentum to indicate this section. It was a translation of the Greek He Kaine Diatheke. The word "testament" can include the ideas of will, covenant, or contract. The Old Testament was called the book of the covenant (Exod. 24:8; 2 Kings 23:2). Paul named it "the old testament" (2 Cor. 3:14). Jeremiah predicted that the old covenant would be supplanted by a new one (Jer. 31:31). Jesus claimed that the new covenant would be established in the blood of His sacrificial death (Matt. 26:28). Later writers continued the contrast between the old covenant made with Israel and ratified by animal blood, and the new covenant made with the church through Christ’s blood (1 Cor. 11:23–25; Heb. 8:6–8). It was only natural that the two sections of the Bible would come to be known as the Old and the New Testaments.

Evangelicals, however, consistently argue for the continuity of the two sections within God’s progressive written revelation. The two are vitally connected as attested by this familiar poem:

The New is in the Old contained,

The Old is in the New explained;

The New is in the Old concealed,

The Old is in the New Revealed.

Classifications

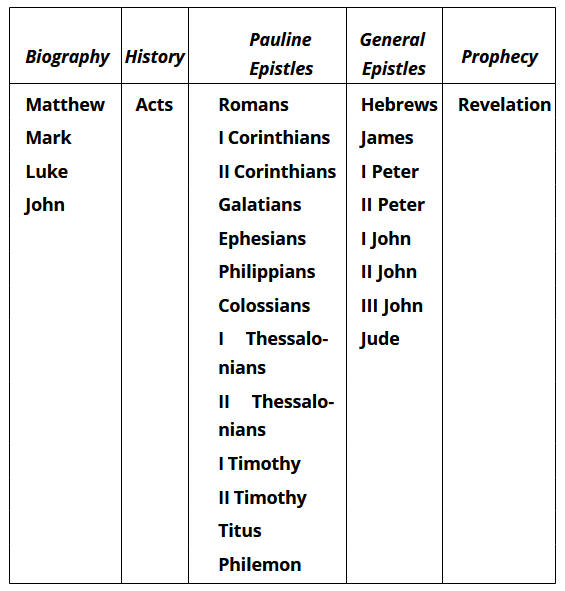

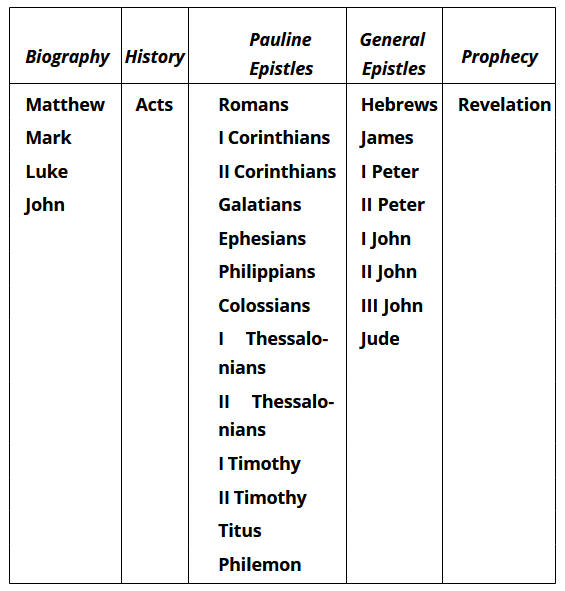

Any classification of these twenty-seven books of the New Testament must admittedly be arbitrary because they were not so catalogued when originally written. However, it has been convenient to group the books by their content and literary style. The present order of the books within our English New Testament has produced this very common listing:

This is a natural division. The New Testament, as should be expected, begins with the four Gospels which depict the advent of the eternal Son of God into the world, His life and ministry here on the earth, His vicarious death and resurrection, and His bodily ascension into heaven. The Book of Acts then records the early history of the church as the gospel is carried by the apostles from Jerusalem to Rome. Once the historical foundation and background of Christianity have been established, its doctrinal significance is then set forth in the Epistles. Since Paul was the most prominent apostle in extending the gospel message throughout the Roman empire, his thirteen Epistles are listed first. There is a question about the human authorship of Hebrews (most believe that Paul wrote it), so it is found right after Paul’s letters and before the acknowledged General Epistles. The term "general" applies both to the content of the books and to their readers. Paul’s letters were sent to specific churches and individuals, whereas the General Epistles, for the most part, had a general circulation. All of the Epistles present solutions to the doctrinal and moral problems of the early church. The New Testament appropriately concludes with the prophetic Book of Revelation. This final book anticipates the ultimate triumph of God’s plan for the ages, the establishment of the kingdom of God on earth, and the eventual creation of the righteous eternal state.

The literary style of the books has also been used as a basis for classification. The first five books are obviously historical in character: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, and Acts. However, these books contain more than just history; they are full of doctrinal and prophetic truths. Because many of the books were written to local churches or groups of believers, they have a distinct ecclesiastical character. These are Romans, I and II Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, I and II Thessalonians, Hebrews, James, I and II Peter, I John, and Jude. These books, however, do contain some historical data, a few personal allusions, and much doctrinal and prophetic material. In fact, the Book of Revelation could be included in this category because it was originally sent to the seven churches of Asia. Some books were sent to individuals and thus have a personal character: I and II Timothy, Titus, Philemon, II and III John. However, even these books deal with local church problems, contain historical information, and present great doctrinal and prophetic passages. Since both Luke and Acts were sent to Theophilus, they could possibly be classified here. Although Revelation is definitely prophetic or apocalyptic in character, the prophetic strain can also be found in the sermons of Christ and the apostles, in the historical narratives, and in the doctrinal exhortations of the Epistles. It must be seen then that these classifications apply only to the general style or character of the books.

Late in his life, the apostle John was instructed by an angel: "Worship God: for the testimony of Jesus is the spirit of prophecy" (Rev. 19:10). Jesus Himself, on the night of His resurrection, told His wondering disciples: "These are the words which I spake unto you, while I was yet with you, that all things must be fulfilled, which were written in the law of Moses, and in the prophets, and in the psalms, concerning me" (Luke 24:44). Look at those final two words again: concerning me. The major theme of the Scriptures is Christ. Through the Bible one comes to know Christ and through Christ he comes to worship and to know God in all His fullness. The following outline expresses this spiritual theme:

Preparation for Christ—Old Testament

Manifestation of Christ—Gospels

Propagation of Christ—Acts

Explanation of Christ—Epistles

Consummation in Christ—Revelation

Some unknown author has aptly written: "If the Old Testament bears witness preeminently to the one who is to come, the New Testament bears witness to the One who has come."

Writers

The twenty-seven New Testament books were written by nine different men. Evangelicals are disagreed over the authorship of Hebrews. If Paul wrote it, then only eight men were directed by the Holy Spirit to give us these books. This chart lists the writers with their respective books.

It is quite obvious that all of the writers were men. They were all Jews, with the possible exception of Luke; however, some feel that he was a Jew with a Greek name (cf. Timothy who had a Jewish mother and a Greek father; Acts 16:1).

Matthew, John, and Peter were members of the original band of twelve apostles (Matt. 10:1–4). Paul became an apostle by the direct revelation and commission of the resurrected Christ (Gal. 1:1, 11–12). Paul called James an apostle and mentioned that James had also seen the risen Lord (1 Cor. 15:7; Gal. 1:19). Luke, although not an apostle, was closely connected with Paul in the latter’s apostolic, missionary ministry. The young church at Jerusalem, including the apostles, met in the home of John Mark (Acts 12:12) who later was identified with the ministries of Paul and Peter (Acts 13:5; Philem. v. 24; 1 Peter 5:13). Jude was the brother of James (Jude v. 1). Therefore, the New Testament was written by apostles, men directly appointed by Christ, and by others closely associated with these same apostles.

Both James and Jude were half-brothers of Christ, probably born to Mary and Joseph after the birth of Jesus (Mark 6:3; Gal. 1:19). Of the eight known authors, only two (Paul and Luke) did not know Jesus during His earthly ministry. Vocationally, John and Peter were commercial fishermen before their apostolic call. Matthew was a publican or tax-collector. Luke was a physician; Paul was a religious Pharisee. Nothing is known about the prior occupations of Mark, James, and Jude. Perhaps the latter two were carpenters like Joseph, their father.

A second look at the chart will reveal that Paul wrote about one-half of the New Testament books, a remarkable achievement considering the fact that he began his ministry much later than the others. In fact, he wrote more books than all of the original apostles put together. Both Paul and Peter used amanuenses or secretaries at times to compose some of their books (Rom. 16:22; 1 Peter 5:12).

Order of Writing

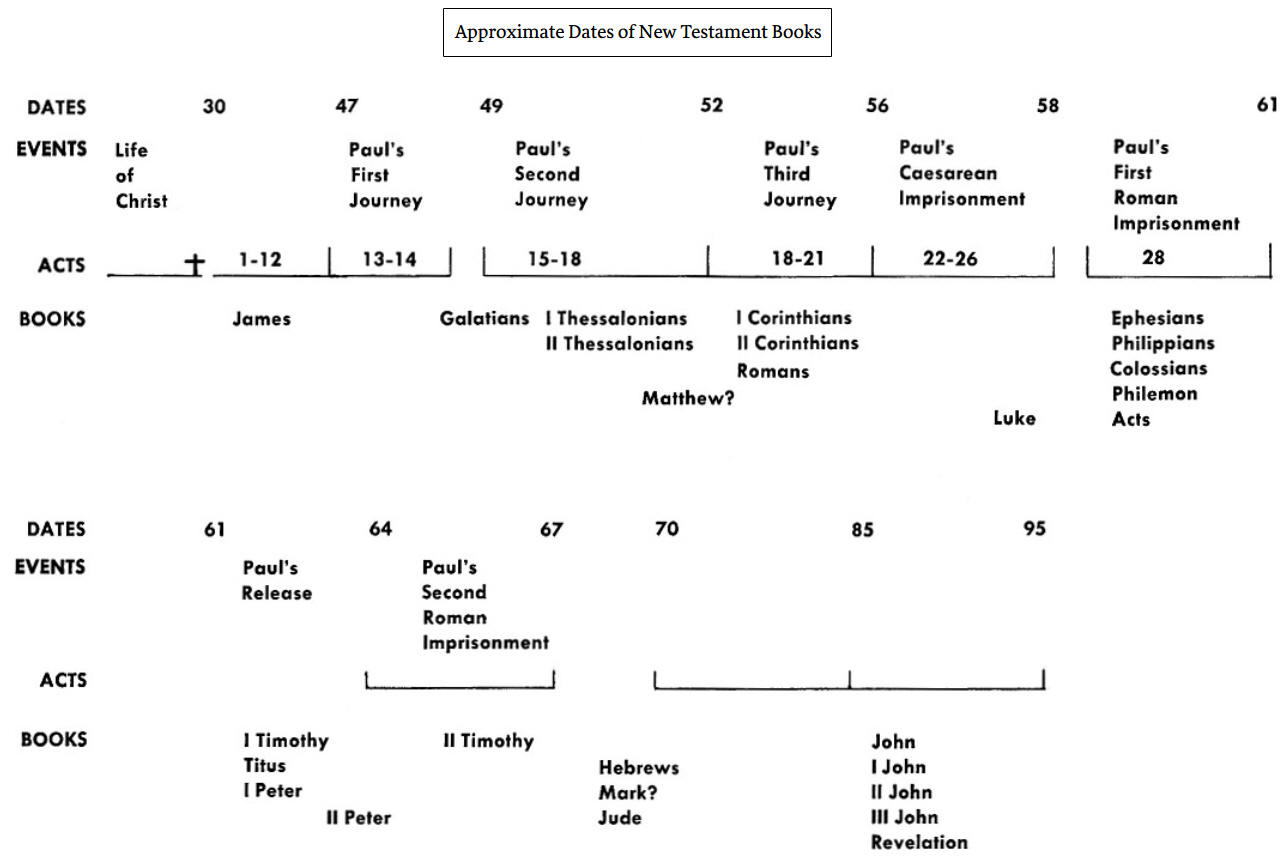

The New Testament books were not written in the order in which they appear in our English Bibles (consult the chart). The Gospels were not written before the Epistles, nor were all of Paul’s letters necessarily penned before the General Epistles. In fact, the Pauline Epistles were not composed in their listed order either. It is generally acknowledged by evangelicals that James was the first and that Revelation was the last to be published.

It is difficult to date all of the books accurately. Because some do not contain any pertinent historical date (II Peter, Jude), it is hard to fit them into the proper first-century background. The Gospels, of course, deal with the life and ministry of Christ without any references to contemporary historical events at the time of writing (cf. the publication of a Lincoln biography today). For this reason, men have debated for decades whether Matthew or Mark was written first.

Using the chart as a guide, notice that no inspired books were produced during the earthly life of Jesus Christ. Neither He nor His apostles wrote then. There is a good possibility that some noninspired accounts of isolated events in our Lord’s life were recorded then and that these were later used as source materials in the composition of at least one Gospel (Luke 1:1–2). There is almost total agreement that no book was written during the first fifteen years of apostolic ministry, a time when the gospel message was practically restricted to Palestine proper (a.d. 30–45; found in Acts 1–12). The Epistles of Paul must be seen against the historical background of his three missionary journeys and two Roman imprisonments (c. 47–67; Acts 13–28). He wrote none during his first trip (a.d. 47–48; Acts 13–14). His first book, Galatians, was probably written in the interval between his first and second journeys. He wrote two books during his second trip (a.d. 49–52; Acts 15:36–18:22), three during his third journey (a.d. 52–56; Acts 18:23–21:17), and none in his Caesarean imprisonment (a.d. 56–58; Acts 22–26). After a troubled, plagued voyage, Paul spent two years in Rome under house arrest, during which time he wrote four books (c. 59–61). After his acquittal, Paul traveled freely in the Mediterranean world and had time to write two more books. When Christianity became a capital offense against the Roman government, Paul was arrested and taken to Rome a second time. During this final imprisonment, he wrote his last book. Outside of James, most of the non-Pauline letters were written late, probably after Paul’s three journeys were over.

It would appear then that twenty-two of the New Testament books were composed during a concentrated period of twenty-five years (a.d. 45–70). This is especially striking when one realizes that the thirty-nine Old Testament books were written over a period of one thousand years (c. 1500–400 b.c.). In the next fifteen years (a.d. 70–85), no books were published. There are probably several reasons for this: The early Christians began to experience the Roman imperial persecutions; the apostolic leaders were being martyred; and survival was foremost in the mind of the church. After the Zerubbabel-Herod temple in Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans in fulfillment of Christ’s prophecy (Matt. 24:1–2), the Christians lived in expectation of Christ’s imminent return. There was an early tradition that Peter would die and that John would not before the second coming of Jesus Christ (John 21:18–24). The martyrdom of Peter and the prolonged life of John would naturally quicken the faith and hope of the early church. Such a background of persecution and expectation would obviate the composition of more books at this time. Late in the first century (85–95), however, the last living apostle, John, wrote the last five books. John had to dispel the notion that he would not die before Christ’s coming (John 21:23). Through him God’s progressive written revelation, begun in Genesis, would end with the writing of Revelation (Rev. 22:18–19). With John’s writings and death in the past, the foundation of this church age had been firmly established (Eph. 2:20). There would be no need for further revelation; the need, from the second century on, would be to promote the written message of God through translation and evangelization.

Inspiration and Authority

Why do Christians value the New Testament so highly? Why are they often erroneously charged with the sin of bibliolatry (worship of the book)? It is because they believe that both of the testaments are the inspired word of God.

What is inspiration? This theological term is based upon the Greek word theopneustos, found only once in the Bible and translated as "given by inspiration of God" (2 Tim. 3:16). It literally means "God-breathed." Evangelicals believe that the written Bible is just as authoritative and just as much the word of God as the oral pronouncements of God Himself. This authority extends equally to all of the sixty-six books and to every word contained within those books. This means that the Christian must regard the entire Bible as the basis of his faith and practice. To him it is inerrant truth, no matter in what area it speaks (theology, ethics, history, science, etc.). The evangelical argues that inspiration refers to what was originally written by the prophets and apostles, not to the men themselves nor to the effect produced within the life of the reader. Although the original texts have been destroyed through various means, the essential text of Scripture has been preserved in the thousands of copies discovered by archaeologists and protected in modern museums and libraries. The science of textual criticism has demonstrated the validity of our present Hebrew and Greek texts upon which our English translations are based. The contemporary Christian can look upon his English Bible with confidence, knowing that he holds in his hands the genuine Word of God without essential loss.

The doctrine of inspiration has not been superimposed upon the Biblical books. This is what they claim for themselves. Critics may reject the claim, but they cannot deny that the claim has been made. Both Paul and Peter made such clear assertions. Paul stated: "All scripture is given by inspiration of God" (2 Tim. 3:16). Peter added: "For the prophecy came not in old time by the will of man: but holy men of God spake as they were moved by the Holy Ghost" (2 Peter 1:21). The Bible was not conceived by man’s imagination and desire; Spirit-moved men produced the God-breathed writings. The human authors recognized that they were divinely blessed and controlled men. Moses knew that he spoke and wrote the words of the Lord (Exod. 24:3–4). David asserted: "The spirit of the Lord spake by me, and his word was in my tongue" (2 Sam. 23:2). More than one prophet knew that the word of the Lord came unto him (Jer. 32:26; Zeph. 1:1; Hag. 1:1). These men were supernaturally authenticated both by miracles and by the fulfillment of their predictions. Israel acknowledged them as genuine divine spokesmen.

Jesus Christ Himself put His stamp of approval upon the Old Testament. His sermons and conversations were saturated with its contents. He used it as a defensive weapon against the satanic temptations (Matt. 4:4, 7, 10). In His debates with His critics, He treated it as the final, authoritative word on the subject at hand (cf. Matt. 12:2–5). He boldly argued that the Scripture could not be broken (John 10:35). He further claimed that not one jot (smallest letter of the Hebrew alphabet) or tittle (a stroke of the pen that distinguished one letter from another) would ever pass from the law (Matt. 5:17–18). The liberal critics have theorized that Jesus accommodated Himself to the naive, ignorant beliefs of His day, but there is no concrete evidence that He ever did. In fact, that would be contrary to His entire life and purpose. He was the truth, He lived the truth, and He spoke the truth.

Christ’s authentication of the Old Testament forms the basis of His preauthentication of the New Testament. Late in His ministry Jesus affirmed: "Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away" (Matt. 24:35). How would we know what His words were if they had not been written down? Do not these words contain a hint of future Scripture writing? The real preauthentication of the New Testament can be seen in Christ’s promise of the ministry of the Holy Spirit in the lives of His apostles. In the upper room on the eve of His crucifixion, He assured His own with these words: "But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you" (John 14:26). Later, He added: "I have yet many things to say unto you, but ye cannot bear them now. Howbeit when he, the Spirit of truth, is come, he will guide you into all truth: for he shall not speak of himself; but whatsoever he shall hear, that shall he speak: and he will shew you things to come. He shall glorify me: for he shall receive of mine, and shall shew it unto you" (John 16:12–14). These verses clearly anticipate the content of the Gospels (all things to your remembrance whatsoever I have said unto you), the Epistles (teach you all things; all truth), and the prophetic section, including Revelation (show you things to come).

The apostles recognized that the content of their teaching and writing was divinely revealed (1 Cor. 2:9–10). Paul clearly stated: "Now we have received, not the spirit of the world, but the spirit which is of God; that we might know the things that are freely given to us of God. Which things also we speak, not in the words which man’s wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual" (1 Cor. 2:12–13). These verses show that Paul saw the fulfillment of Christ’s promise within his own ministry. He knew that God had invested him with divine authority (1 Cor. 14:37; 2 Cor. 10:8). Each apostle, himself divinely authenticated, recognized the divine authority of the other: Peter of Paul (2 Peter 3:15–16); Paul of Luke (1 Tim. 5:18); and Jude of Peter (Jude vv. 17–18; cf. 2 Peter 3:3). They regarded the books of the two testaments to be of equal authority (in 1 Tim. 5:18 Deuteronomy and Luke are so equated).

As an obedient Christian, a child of God must share Christ’s attitude toward the Old Testament and His preauthentication of the New. To him the Bible is no mere human composition; it is the living word of the living God. He needs it to sustain his spiritual life. He needs it in order to know what to believe and how to live. This is why he studies it with a deep respect.