8

ACTS

Writer

The authorship of Acts was discussed previously (cf. Luke, pp. 109–11). The internal evidence of both books has corroborated the testimony of tradition that Luke, the beloved physician and companion of Paul, wrote them. The first verse of Acts refers to an earlier volume written to the same individual, Theophilus; only the Gospel of Luke could qualify as that "former treatise."

Some believe that the prologue to the Gospel (1:1–4) also serves as the prologue to Acts. This would mean that Luke’s original plan was to write two volumes to give Theophilus "certainty of those things, wherein thou hast been instructed" (Luke 1:4). The first dealt with the person and earthly ministry of Jesus Christ, whereas the second treated the history and outreach of the early church. In the first was the record "of all that Jesus began both to do and teach" (Acts 1:1) and the second revealed what Christ continued to do and teach through the Holy Spirit in the lives of the apostles. The continuity in the two books can also be seen in the overlap of content between the closing verses of the Gospel (24:46–53) and the opening verses of Acts (1:1–12).

Since Luke researched the content of the Gospel, he doubtless used the same technique for Acts. He was acquainted firsthand with some of Paul’s missionary activities (16:10–17; 20:5–28:31). During his traveling days with Paul, he would have had many opportunities to talk with Christians from such important cities as Jerusalem and Caesarea (cf. 21:8, 17). Much could be learned from men like Philip and Mnason (21:8, 16), from others in Paul’s team (Silas, Timothy, Mark), and from the apostles themselves. It would have been very easy for Luke to have compiled his historical data on the early church during the two years that Paul was interned in Caesarea (24:27).

Time and Place

Many liberals speculate that the author of Acts was dependent upon Josephus, a late first-century Jewish historian; therefore, they date the book very late, anywhere between a.d. 80 and a.d. 130. However, there is no objective, external testimony from church history for doing so. The historical movement of the book actually ends with Paul’s first Roman imprisonment which lasted two years (28:16, 30). The book concludes rather abruptly especially since Paul was freed and traveled for a few more years in the Mediterranean area, visiting churches that he had earlier founded. The only logical position is that Luke finished the writing of The Acts during the two-year internment at Rome. This would give a date of a.d. 59–61, although some evangelicals date this imprisonment a.d. 58–60 or a.d. 61–63. It is difficult to arrive with absolute certainty at fixed dates for some of the New Testament events; however, it is safe to assume that the book was composed before these significant events: the burning of Rome (a.d. 64), the first imperial persecution of Christians (a.d. 64–67), the second Roman imprisonment of Paul (a.d. 64–67), the Jewish rebellion against the Romans (a.d. 66), and the destruction both of Jerusalem and the Jewish temple by the Romans (a.d. 70). Surely Luke would have incorporated these events into his book if he had written after their occurrences.

Purposes

The purpose—to confirm Theophilus in the faith—has already been mentioned (under Writer, p. 149). The Gospel indoctrinated him in the person and ministry of Jesus Christ; this book was designed to instruct him about the lives and activities of the apostles (1:1–2). Luke’s method of instruction will be seen in the other purposes.

Luke wanted Theophilus to be aware of the geographical outreach of the gospel message. Christ’s instructions to the apostles provided the general outline of his book, showing how the gospel was taken from Jerusalem to Rome: "But ye shall receive power, after that the Holy Ghost is come upon you: and ye shall be witnesses unto me both in Jerusalem, and in all Judaea, and in Samaria, and unto the uttermost part of the earth" (1:8).

Acts 1–7 (Jerusalem)

Acts 8 (Judea and Samaria)

Acts 9–28 ("Uttermost Part"—Syria, Phoenicia, Asia Minor, Greece, and Italy)

Luke emphasized the northern and western propagation of the gospel (into Asia Minor and Europe). Nothing is given on the apostolic thrust into the south (Africa) or the east (Babylon and Persia), although converts from those regions are mentioned (2:9–10; 8:27). In the early months the apostles restricted their ministry to the area around Jerusalem (chs. 1–7). Later, the gospel was carried into Judea and Samaria (8:1), Damascus in Syria (9:19), Lydda (9:32), Joppa (9:36), Caesarea (10:1), Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Antioch in Syria (11:19). Strong, lengthy missionary activity did not begin until the call of Paul and Barnabas (13:1–2). This first missionary tour led them to the island of Cyprus and to the central section of Asia Minor where they evangelized the cities of Antioch in Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra, and Derbe (chs. 13–14). Paul’s second journey took him into the regions of Syria, Cilicia, and Mysia and to the European cities of Philippi, Thessalonica, Berea, Athens, and Corinth (15:36–18:22). In his third journey, Paul concentrated on the strategic city of Ephesus, but he also returned to the Greek mainland where he visited the churches established during the second trip (18:23–21:17). When as a Roman prisoner Paul finally arrived in Rome, the gospel had already preceded him to that great city (28:14–16).

In addition to tracing the geographical outreach of the gospel, Luke wanted to mark the numerical growth of Christianity from the small beginning in the upper room in Jerusalem to a multitude of people that filled the Roman empire. He did this by inserting statistics and summaries at strategic intervals: "and the same day there were added unto them about three thousand souls" (2:41); "and the Lord added to the church daily" (2:47); "the number of the men was about five thousand" (4:4); "and believers were the more added to the Lord, multitudes both of men and women" (5:14); "and the word of God increased; and the number of the disciples multiplied in Jerusalem greatly" (6:7); "then … the churches … were multiplied" (9:31); "and a great number believed" (11:21); "but the word of God grew and multiplied" (12:24); "and so were the churches … increased in number daily" (16:5); and "so mightily grew the word of God and prevailed" (19:20). The reaction of the Thessalonian Jews to Paul’s missionary team serves as a fitting evaluation and illustration of the numerical growth: "These that have turned the world upside down are come hither also" (17:6).

A corner of the Roman forum at Salamis, on the island of Cyprus.

Luke also wanted to show that Christianity was not a political threat to Rome, but that it was basically spiritual in essence. Some have suggested that Luke researched the activities of the apostles, especially those of Paul, as part of Paul’s defense before Caesar in Rome. This plausible view is supported by the closing verses of the book:

And Paul dwelt two whole years in his own hired house, and received all that came in unto him, Preaching the kingdom of God, and teaching those things which concern the Lord Jesus Christ, with all confidence, no man forbidding him (28:30–31).

After Paul had been arrested in Jerusalem for an alleged violation of temple worship, he asked that his case be heard by Caesar himself. As a Roman citizen, he had this right. Apparently the Roman government did not find anything politically offensive in Paul because they did not forbid him to preach. They recognized that a person could be a member of the spiritual kingdom of God and a Roman citizen at the same time without any real conflicts.

Luke then desired to demonstrate that unbelieving Jews were the real persecutors of Christians and that frequently they stirred up the Gentile populace and the political authorities to accomplish their selfish, wicked ends. In other words, the Jews, not Paul, should have been on trial for civil disturbances. Just as they successfully forced Pilate to have Jesus crucified so, as Luke wanted to prove, they were trying to get the Romans to eliminate another one of their foes, namely Paul. It was the priests and Sadducees who imprisoned and threatened Peter and John because the latter preached the resurrection of Jesus, a truth they denied (4:1–3, 21). This same group later imprisoned, threatened, and beat the apostles (5:17–18, 40). They stoned Stephen to death for religious reasons (7:54, 58). Through Saul, they drove Christian Jews out of Jerusalem (8:1–3). After Saul was converted, the Jews tried to kill him even though he was one of their former associates (9:23). James was killed and Peter imprisoned because Herod Agrippa I saw that it pleased the Jews (12:1–3). The Jews of Antioch in Pisidia stirred up "the devout and honourable women, and the chief men of the city" to persecute Paul and Barnabas and to expel them from the city (13:50). They repeated these actions in Iconium and Lystra, actually stoning Paul and leaving him for dead (14:1–2, 19). The Jews of Thessalonica forced him out of both Thessalonica and Berea by falsely accusing Paul before the authorities and the people (17:5–9, 13). When the Corinthian Jews "made insurrection with one accord against Paul" before Gallio, the deputy of Achaia, Gallio saw that their hatred was religiously, not politically, motivated (18:12). The Jews worked cleverly to stir up the idolatrous Ephesian silversmiths to persecute the Christians (19:33). The Jews later plotted against the life of Paul (20:3; 21:31; 23:12). Civil authorities constantly confirmed the political innocence of Paul in spite of false Jewish charges (17:2–7; 19:35–41; 26:31–32).

Paul wrote that the gospel was "the power of God unto salvation to every one that believeth; to the Jew first, and also to the Greek" (Rom. 1:16). Luke wrote to show that the apostles in spite of strong, frequent Jewish opposition, continued to preach to the Jew first. They were given many opportunities to believe, and yet they rejected the message of Christ through the apostles just as they had rejected the ministry of the Lord Himself (John 1:11). The early preaching of the apostles was limited to Jewish audiences. When the Christians were forced out of Jerusalem into Gentile regions, they initially witnessed only to Jews in those areas (8:4; cf. 11:19–20). Wherever Paul went, he constantly preached to Jews, both in and out of their synagogues, before he began a Gentile ministry (13:5, 14; 14:1; 16:13; 17:1, 10, 17; 18:4; 19:8; 28:17). Although God had worked in and through Israel from the time of Abraham to Christ, the church age is basically a Gentile period of blessing. Luke vindicated this change of divine operation by presenting the authenticated offer to the Jews of the Christian message, the rejection of that offer by them, and the outreach of the Gentiles. Paul’s words in the synagogue at Antioch in Pisidia provide a fitting condensation of this purpose: "It was necessary that the word of God should first have been spoken to you: but seeing ye put it from you, and judge yourselves unworthy of everlasting life, lo, we turn to the Gentiles" (13:46). The book ends with this same conclusion and intention: "Be it known therefore unto you [Jews], that the salvation of God is sent unto the Gentiles, and that they will hear it" (28:28).

Distinctive Features

Acts is a book of firsts. It narrates the first election of a church officer (1:23–26), the first sermon of the new era (2:14–40), the first conversions (2:41), the first miracle (3:1–11), the first persecution (4:1–4), the first chastisement (5:1–11), the first deacons (6:1–7), the first sermon by a layman (7:2–53), the first Christian martyr (7:54–60), the first Gentile converts (10:44–48), the first time the name "Christian" is mentioned (11:26), the first apostolic martyr (12:2), the first call to missionary service (13:1–2), the first church debate or council (15:1–30), and the first preaching in Europe (16:12–13).

Acts must also be seen as a transitional book. It bridges the gap between the Gospels and the Epistles, between the ministry of Christ and the activities of the apostles. It is therefore an introductory book, full of historical background. Great care must be exercised lest one build his entire theological position of doctrine and practice upon what is found in its chapters. Doctrine must be primarily based upon the Epistles where apostolic teaching is spelled out in detail. Many events recorded in Acts were never intended to become a pattern for every generation of Christians to follow. For instance, no one should expect to be personally taught by the resurrected Christ as were the apostles (1:1–3). The phenomena of wind, cloven fiery tongues, and tongues-speaking should not be anticipated by the believer in the entrance of the Holy Spirit into his life (2:1–4). Christians do not have to sell their possessions as the early converts did (2:45; 4:34). Deliberate liars are not immediately struck dead today (5:1–11). Imprisoned Christians should not expect to be released by an angel (5:19; 12:7) or by an earthquake (16:26). Paul himself later experienced at least three other imprisonments in which no angel or earthquake came to his rescue. Should martyrs today expect to see the resurrected Christ as Stephen did (7:55)? Should soul winners expect to be transported from one geographic location to another by the Spirit as was Philip (8:39)? Should people expect to see the resurrected Christ before their conversion as did Paul (9:1–6)? Should unsaved men expect an angelic invitation informing them what evangelist to secure as did Cornelius (10:1–8)? The answers to these questions are obviously negative. In Acts God was doing a new thing; He was starting the church age which has lasted now for almost two thousand years. In the divine introduction were many unusual signs and miracles that were never designed to be sought after by later Christians. God practiced this same principle in earlier ages. When the law was given to Moses originally the event was accompanied by thunder, lightning, smoke, and an earthquake (Exod. 19:16–18); however, when the law was given the second time, these phenomena were not repeated (Exod. 34). Why? Because the age of the law had already begun. God nourished the children with daily manna for forty years, but once the Israelites were in Canaan, the manna stopped. They were to work the land and to trust the Lord for its increase; they were not to expect a repetition of the manna provision.

The Holy Spirit is mentioned over fifty times in this book, more than in any other New Testament book. It is no wonder that some have dubbed it "The Acts of the Holy Spirit." Many important aspects of pneumatology can be drawn from Luke’s narratives. His personality is demonstrated by the facts that He can be lied against (5:3), tempted (5:9), and resisted (7:51). His works are many and varied. Christ predicted that believers would be baptized in Him (1:5). By Him Christians are filled (2:4), comforted (9:31), commissioned to service (13:2), directed to the right fields of ministry (16:6–7), and appointed as pastors (20:28). He inspired the Old Testament (1:16; 28:25), caused the apostles to speak in tongues (2:4), witnessed to the death and resurrection of Christ (5:32), transported Philip (8:39), and guided the deliberations of church leaders (15:28). His entrance into the world and into the lives of believers is described in several ways: coming upon (1:8), poured out (2:17), promised (2:33), a gift (10:45), and being received (10:47).

Luke also emphasized prayer. Every chapter shows the result of earnest prayer and almost every chapter makes mention of it by name (1:14; 2:42; 3:1; 4:24; 6:4; 7:60; 8:15; 9:11; 10:2; 11:5; 12:5; 13:3; 14:23; 16:13; 20:36; 21:5; 22:17; 27:35; 28:15).

Acts is basically a book of mission and witness. Jesus charged: "… ye shall be witnesses unto me" (1:8). They were to evangelize the world, spreading the good news of Christ’s person and redemptive work, including His vicarious death and bodily resurrection. It was agreed that Judas’ replacement had to have seen the resurrected Christ (1:22). Peter proclaimed his witness to the Jewish pilgrims on the day of Pentecost (2:32), to the temple crowd who marveled over the healed lame man (3:15), to the antagonistic priests (5:32), and to the Gentile household of Cornelius (10:39–41). Paul witnessed to Christ’s person and work in the synagogue at Antioch in Pisidia (13:31) and before Roman authorities (26:16, 22).

The concept of witness can also be seen in the twelve sermons dotted throughout the book. Four sermons of Peter are recorded: on the day of Pentecost (2:14–41), to the Jews at Solomon’s porch in the temple (3:12–26), at Cornelius’ house in Caesarea (10:34–43), and before the apostles and elders (15:7–11). Six sermons by Paul are condensed in the book: in the synagogue at Antioch in Pisidia (13:14–43); before the philosophers on Mars’ Hill in Athens (17:22–31); his farewell address to the Ephesian elders at Miletus (20:17–38); and his defenses before the hostile Jerusalem crowd (22:1–22), before the Roman governor Felix (24:10–21), and before Herod Agrippa II (26:1–24). James’ concluding remarks at the Council in Jerusalem (15:13–21) and the extensive summary and commentary on the Old Testament by Stephen (7:2–53) complement the sermons by the two major apostles.

Not only the sermons but also the signs, or miracles, of the apostles are recorded. Paul wrote concerning himself: "Truly the signs of an apostle were wrought among you in all patience, in signs, and wonders, and mighty deeds" (2 Cor. 12:12). The messages of the apostles were authenticated by divinely wrought miracles. Not all of their miracles were narrated by Luke, but a sufficient number is given to illustrate the typical apostolic ministry. Three instances of healing are attributed directly to Peter: healing of the lame man (3:1–11), strengthening the palsied Aeneas (9:32–35), and raising Dorcas from the dead (9:36–43). Five were performed by Paul: curing the cripple at Lystra (14:8–10), casting out the demonic spirit of divination at Philippi (16:16–18), restoring Eutychus, who had fallen (20:6–12), shaking the snake off his hand (28:1–6), and healing the feverous father of Publius at Melita (28:7–8). Miracles were also performed as demonstrations of chastisement and judgment: the deaths of Ananias and Sapphira (5:1–11), the sudden death of Herod Agrippa I (12:20–23), and the blindness of Elymas (13:6–12). In addition, there are general statements mentioning the healing of many people by Peter, Philip, Stephen, and Paul without giving any particulars (5:12–16; 6:8; 8:6; 19:11–20; 28:9) Also, many unusual supernatural phenomena occurred during the ministry of the early church: the bodily ascension of Jesus (1:9), the wind, fiery tongues, and glossolalia at the coming of the Spirit (2:1–4), the release of Peter from prison by an angel twice (5:19; 12:7), the transport of Philip (8:39), and the angelic visitation to Cornelius (10:1–6).

Acts contains four chapters in which unusual receptions of the Holy Spirit are narrated (2, 8, 10, 19). On the day of Pentecost (2:1–13), the Jewish apostles in Jerusalem were both baptized in the Spirit (2:2) and filled by Him (2:4). This event was accompanied by the sound of a rushing mighty wind, cloven fiery tongues appearing above them, and speaking in tongues. The tongues-speaking was in foreign languages and dialects understood by the unsaved Jewish audience without any interpretation. There is no mention that the apostles were praying for this experience nor that they laid hands on each other. Jesus had earlier prayed that they might receive the Spirit (John 14:16) and promised to send the Spirit to them after His death, resurrection, and ascension (John 16:7). The Spirit thus came on Pentecost in fulfillment of Christ’s prayer and plan. This was the official beginning of our present church era, a nonrepeatable event similar to the first coming of Christ. When the apostles in Jerusalem heard of the evangelistic success of Philip in Samaria, they sent Peter and John to the converts (8:5–25). After Peter and John prayed for the new believers and laid hands on them, they received the Holy Spirit. There is no mention of wind, fiery tongues, or tongues-speaking. There is no indication that the Samaritans prayed or laid hands on each other nor that Philip shared the apostolic power. This time interval between faith and the reception of the Holy Spirit demonstrated to the Samaritan converts that they had to be under the spiritual authority of Jewish apostles, appointed by Christ and stationed in Jerusalem. The third unusual reception occurred when Peter preached for the first time to a Gentile, Cornelius, in Caesarea (10:1–48). While Peter was preaching, Cornelius believed, received the Holy Spirit, and spoke in tongues. After this experience, he was baptized in water. Again, there is no indication that Cornelius prayed for this to happen to him. Also, Peter did not pray for or lay hands on him. This unusual reception was a sign to Peter and to the believing Jews that God could save Gentiles and that in this age, Jews and Gentiles share an equal spiritual position before God. The final unique reception occurred when Paul led twelve disciples of John the Baptist into more complete truth about Christ (19:1–7). In essence, they were Old Testament saints living in the New Testament era. They were looking for the coming of Christ when He had already come. To confirm his message, Paul laid hands on them and they received the Spirit, externally attested by tongues-speaking. Again, there is no evidence that they prayed for this experience or that they laid hands on each other. In these four chapters the Spirit of God was being formally introduced to four classes of people: Jews, Samaritans, Gentiles, and Old Testament saints. In all four events, an apostle was vitally involved. These chapters were not designed to provide model experiences for all future generations of Christians to follow.

The Roman theater at Caesarea

Acts is very important to the Bible student because it provides the historical background for many of the Epistles. No one should undertake the study of the following books until he has first examined the accounts in Acts where these churches were established or mentioned: Romans (28:14–31); I and II Corinthians (18:1–18); Galatians (13:3–14:28); Ephesians (19:1–41); Philippians (16:6–40); I and II Thessalonians (17:1–9); I Timothy (19:1–41; 20:17–38); and Titus (27:1–13).

Luke’s reputation as an historian and geographer has been challenged, but the conclusions of archaeologists have always supported him. He was the only New Testament writer to mention any Roman emperors by name: Augustus (Luke 2:1) and Tiberius (Luke 3:1). In his identification of political leaders, he always used the terms properly even though the positions changed frequently. This would have required him to have primary information about various political offices in different parts of the Roman empire. Both Sergius Paulus (13:7) and Gallio (18:12) were correctly titled as anthupatoi (deputies or proconsuls), officials in charge of senatorial provinces. The magistrates at Philippi were strategoi (16:20, 22, 35, 36, 38). The "rulers of the city" of Thessalonica were properly called politarchoi (17:6, 8). He knew that the town clerk or scribe (grammateus; 19:35) at Ephesus had political authority over the people and responsibility toward Rome. He was aware that Felix the governor (hegemon; 23:24) held the same position in Judea that Pilate once had (Matt. 27:11), the ruler of an imperial province. "The chief man of the island" (28:7) of Malta was literally "the first man" (ho protos), a technical term for the ruling official. For these reasons, Luke must be known as a first-class ancient historian.

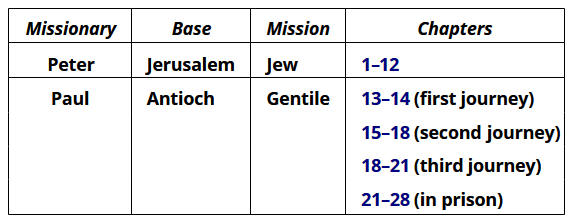

Luke structured his book in a simple fashion:

Although called "The Acts of the Apostles," the book stresses the activities of only two of them, Peter and Paul. The first twelve chapters deal with the outreach of Peter toward the Jew from the church at Jerusalem. The closing chapters deal with Paul’s ministry mainly to the Gentiles from his home church at Antioch in Syria. Paul’s life is divided into two sections: his three missionary journeys (13:1–21:17) and his defenses of the Christian faith as a Roman prisoner (21:18–28:31).

Outline

I. The Witness in Jerusalem (chs. 1–7)

A. The ascension of Christ (1:1–11)

B. The appointment of Matthias (1:12–26)

C. The coming of the Holy Spirit (2:1–13)

D. The message of Peter (2:14–41)

E. The fellowship of the early church (2:42–47)

F. The healing of the lame man (3:1–11)

G. The message of Peter in the temple (3:12–26)

H. The threat of the religious leaders (4:1–22)

I. The reaction of the church (4:23–37)

J. The chastisement of Ananias and Sapphira (5:1–11)

K. The performing of various miracles (5:12–16)

L. The persecution by the religious leaders (5:17–42)

M. The appointment of deacons (6:1–7)

N. The preaching of Stephen (6:8–7:53)

O. The martyrdom of Stephen (7:54–60)

II. The Witness in Judea and Samaria (chs. 8–12)

A. The persecution of the Jerusalem church (8:1–4)

B. The evangelization of Samaria (8:5–25)

C. The conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch (8:26–40)

D. The conversion of Saul (9:1–31)

E. The healing of Aeneas (9:32–35)

F. The raising of Dorcas (9:36–43)

G. The conversion of Cornelius (10:1–48)

H. Peter’s report to the Jerusalem church (11:1–18)

I. The ministry at Antioch (11:19–30)

J. The martyrdom of James (12:1–4)

K. The imprisonment of Peter (12:5–19)

L. The death of Herod (12:20–25)

III. The Witness to the Uttermost Part (chs. 13–28)

A. Paul’s first missionary journey (13:1–14:28)

1. His commission (13:1–3)

2. On Cyprus (13:4–13)

3. At Antioch in Pisidia (13:14–52)

4. At Iconium (14:1–5)

5. At Lystra and Derbe (14:6–20)

6. Return trip to Antioch (14:21–28)

B. The council at Jerusalem (15:1–35)

1. The problem (15:1)

2. The deliberations (15:2–21)

3. The solution (15:22–35)

C. Paul’s second missionary journey (15:36–18:22)

1. Dissension with Barnabas (15:36–41)

2. Appointment of Timothy (16:1–5)

3. At Philippi (16:6–40)

4. At Thessalonica (17:1–9)

5. At Berea (17:10–14)

6. At Athens (17:15–34)

7. At Corinth (18:1–18)

8. Return trip to Antioch (18:19–22)

D. Paul’s third missionary journey (18:23–21:17)

1. Ministry of Apollos (18:24–28)

2. At Ephesus (19:1–41)

3. In Greece (20:1–5)

4. At Troas (20:6–12)

5. At Miletus (20:13–38)

6. Return trip to Jerusalem (21:1–17)

E. Paul’s imprisonment (21:18–28:31)

1. His arrest in the temple (21:18–40)

2. His defense before the multitude (22:1–30)

3. His defense before the Sanhedrin (23:1–10)

4. The conspiracy to kill Paul (23:11–22)

5. His departure to Caesarea (23:23–35)

6. His defense before Felix (24:1–27)

7. His defense before Festus (25:1–27)

8. His defense before Agrippa (26:1–32)

9. His voyage to Italy (27:1–44)

10. His ministry at Melita (28:1–10)

11. His arrival at Rome (28:11–31)

Survey

1:1–11

For forty days after His resurrection, Jesus appeared to His disciples and taught them. Their witness to the world could not begin until the Holy Spirit had come upon them; therefore He commanded them to remain in Jerusalem. He would send the Holy Spirit to them as He had promised earlier (John 14:16–17, 26; 15:26–27; 16:7–14). The disciples thought that now that Christ had suffered He could establish the earthly kingdom; however, He cautioned them not to speculate about eschatology, but to bear witness of Him throughout the world in the enabling ministry of the Holy Spirit. The disciples saw the Lord ascend into heaven and received the promise of the angels that He would return in like manner.

1:12–26

During the interval, the group of one hundred twenty disciples voted for Matthias over Joseph to fill the apostolic vacancy created by Judas’ betrayal and death. Men have debated whether their action was justified. Should Paul have been the twelfth apostle? How could they make the decision apart from the ministry of the Spirit who had not yet come? Did they still have the indwelling presence of the Spirit given to them by Christ shortly after His resurrection (John 20:19–23). Regardless, Matthias was chosen and was recognized as a genuine apostle.

2:1–13

The descent of the Holy Spirit ten days after Christ’s ascension on the day of Pentecost was marked by three unusual phenomena: the sound of a rushing mighty wind, fiery cloven tongues appearing over them, and speaking in tongues. The Jewish pilgrims were amazed that the Galilean apostles could speak in their native languages and dialects (glossa: 2:4, 11, and dialektos: 2:6, 8). While some wondered, others attributed the tongues-speaking to drunkenness. At this time, the apostles were both baptized in the Spirit (1:5; cf. 2:2) and filled with the Spirit (1:8; cf. 2:4).

2:14–21

Peter explained that the descent of the Spirit was like that predicted by Joel. Joel’s prophecy will be fulfilled in the last days of Israel’s history, at the end of the great tribulation just prior to Christ’s second advent to the earth to destroy the wicked nations and to establish His earthly kingdom (Joel 2:20–3:21). The signs written by Joel and quoted by Peter did not occur on the day of Pentecost. This is why Peter said "this is that" rather than "it is written" or "it is fulfilled." Peter’s purpose was to show that the Old Testament predicted such an outpouring of the Spirit. Just as the Messiah one day will pour out the Spirit upon Israel, so He has poured out the Spirit upon the church in this age.

2:22–41

Peter then focused his message on the person of Christ. He stated that Christ had been divinely authenticated through His public display of miracles and healing. He then argued that their wicked crime of crucifixion and the subsequent resurrection of Jesus were both part of God’s predetermined plan. God is definitely able to use the free-will actions of men, whether they be good or evil, to accomplish His ultimate goals: the glorification of Himself and the blessing of His people. He logically claimed that David in his psalm predicted the death and the resurrection of the Messiah. When Jesus died, His body was placed into Joseph’s tomb and His soul went into hell (Hades), but His soul did not remain in hell nor did His body begin to decompose (2:31). Peter then concluded that the resurrected, ascended Christ had sent the Spirit into the world and into the apostles’ lives in this dramatic fashion. What they saw and heard (2:33) was a sign to them of their error and sin in rejecting Christ. Convicted by the Spirit, they asked: "What shall we do?" Peter’s answer has puzzled many (2:38). Did he mean that water baptism was essential to gain the remission of sins? An affirmative answer would contradict the clear teaching of Scripture elsewhere (Rom. 5:1; Eph. 2:8–9). The inward faith-repentance that secures the remission of sins will outwardly manifest itself in an open identification with Christ’s redemptive work through water baptism. Baptism is a confession, the first work that faith produces. Three thousand received the word (repented and believed) and were baptized.

2:42–47

Although the early church increased rapidly in numbers, it maintained a strong spiritual quality. It was marked by doctrinal conformity, fellowship, constant observance of the communion ordinance, prayer, apostolic miracles, communal sharing of property, and joy. These Jewish believers continued to worship in the temple, but they also congregated "from house to house" (house-churches scattered throughout Jerusalem).

3:1–26

The healing of the lame man at the Beautiful Gate of the temple provided Peter another major opportunity to preach to a large Jewish multitude. He claimed that the miracle was caused through faith in the crucified, resurrected Christ, not through the human power and holiness of the apostles. His appeal was simple: "Repent ye therefore, and be converted, that your sins may be blotted out …" (3:19; note the omission of baptism as a prerequisite for salvation; cf. 2:38). They needed to repent (change their mind) of their rejection of Christ and to accept Him before His return in fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy.

4:1–31

There was a mixed reaction to Peter’s message. Many believed, increasing the Jerusalem church from over three thousand to about five thousand (2:41; cf. 4:4). However, the priests and Sadducees imprisoned Peter and John for the night. At their "trial" before the religious council the next day, the apostles again claimed that the miracle was wrought by the resurrected Christ, whom the leaders had rejected and in whom only could salvation be found. Unable to contradict the evidence of the healed man, they threatened the apostles about any further preaching; however, the latter refused to comply. Their release and return to the church caused a great prayer meeting in which they asked for boldness to preach and to heal in the face of such hostile opposition.

4:32–5:11

The unity of the early Christians ("of one heart and of one soul") could be seen in their attitudes toward material possessions. They sold their lands and houses, placed the sale money into apostolic care, and distributed to the needs of the group. In this financial demonstration of love for one another, no one suffered want. Some apparently had lost jobs and homes because of their new faith. The deception of Ananias and Sapphira must be seen against this display of general generosity. They lied to God the Holy Spirit (5:3; cf. 5:4) rather than to men when they deliberately plotted to keep back part of the sale price of their property. Their sudden deaths were not only a display of divine chastisement but also an indication of apostolic authority in retaining sin rather than remitting it (John 20:23). It further demonstrated that sin could not be tolerated within a church desirous of God’s blessing and power.

5:12–42

The continuous ministry of healing by the apostles so vexed the Sadducees that they placed the former in prison. Released by an angel that night, the apostles were arrested a second time for preaching in the temple. Their trial or inquisition resembled that of Christ before the ruling elders. When the apostles reaffirmed their determination to preach the gospel, the council decided to kill them. Gamaliel, a Pharisaical doctor of the law, warned them against such hasty action. He argued that God’s work could not be resisted and that man’s work would eventually die out. He suggested that time alone would determine the source of the apostolic ministry. The leaders agreed not to kill the apostles, but they did beat and threaten them. The apostles reacted with joy and constant witnessing.

6:1–7

Increase of numbers often brings neglect of people. In the early church the material needs of Christian widows were supplied by the common treasury administered by the apostles. As the converts increased numerically, the needs of some widows were being neglected. There were too many widows and too few apostles. The apostles recognized that their first responsibilities were to preach and to pray. They asked that the church select seven qualified, spiritual men whom they might appoint to administer the widow welfare program. After this was done, the church experienced another growth spurt.

6:8–7:60

Stephen, one of the appointed seven, extended his ministry into healing and preaching. He was so effective that the religious council brought false charges against him and arrested him. Their accusation of his message probably reflected a faulty interpretation of Jesus’ prediction of the destruction of the temple (6:3–14; cf. Matt. 24:1–2). In his lengthy message, Stephen indicted both them and their ancestors for constantly rejecting the message of God’s appointed servants and for resisting the ministry of the Holy Spirit. When they became enraged, the heavens opened and Stephen saw Jesus at the right hand of the Father. When he testified of his vision, they began to stone him. Just before he died, he uttered two short prayers, one for himself and one for his murderers. The attitude in which he died no doubt troubled the conscience of Saul (who after his conversion became Paul the apostle).

8:1–4

The stoning of Stephen ignited a major persecution, led by Saul, against the church at Jerusalem. Although the apostles bravely stayed in Jerusalem, many scattered throughout Judea, Samaria, and such foreign regions as Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Syria. As they went, they preached the word but limited their early ministry to Jews in those areas (cf. 11:19).

8:5–40

Philip, a deacon-evangelist (6:5; 21:8), ministered in Samaria, preaching, healing, and casting out demons. The strange way in which his converts received the Spirit was discussed earlier. The ecclesiastical sin of simony (purchasing a church office through money) was condemned by Peter when he rebuked Simon, the converted (?) sorcerer. Philip’s leaving Samaria to witness to the Ethiopian eunuch demonstrated that God was (and is) just as interested in individuals as in the masses. This account also shows that God will reveal truth about Jesus Christ to those who are genuine worshipers of God and who desire to know the teaching of Scripture. After the conversion and baptism of the eunuch, Philip was supernaturally caught away. He later located at Caesarea (21:8).

The site of Jacob’s well (center) and the surrounding Samaritan countryside, as viewed from the slopes of Mount Gerizim.

9:1–31

On his way to Damascus to arrest Christians, Saul was struck blind and converted by the glorious revelation of Christ. Ananias, under divine instructions, went to the blind Saul, healed him of his blindness, laid hands on him, and baptized him. Immediately Paul began to witness in the synagogue at Damascus. When the enraged Jews plotted to kill him, Saul escaped and went to Jerusalem where the apostles received him because of Barnabas’ testimony. Later, Paul returned to his hometown of Tarsus because of Jewish hostility at Jerusalem.

9:32–43

Peter meanwhile extended his ministry into Lydda where he healed the palsied Aeneas and into Joppa where he raised the benevolent Dorcas from the dead.

10:1–11:18

At this time Cornelius, a good but unsaved Roman soldier in Caesarea, was charged by an angel to send for Peter. God was preparing Peter for this opportunity to preach to a Gentile for the first time by giving a vision to him. At first Peter did not understand the significance of the vision, but later, after talking with Cornelius’ emissaries and with Cornelius himself, he knew that God wanted him to preach to Gentiles as well as to Jews. In his message Peter preached the necessity of faith in Christ to receive the remission of sins. The providentially prepared hearts of Cornelius and his friends responded. The unusual phenomenon of tongues-speaking that accompanied their conversion experience was discussed earlier (see p. 157). Back in Jerusalem, Peter was criticized for sharing the gospel with Gentiles until he explained the complex circumstances surrounding his visit to the house of Cornelius.

11:19–30

The ministry at Antioch in Syria among the Grecian Jews (hellenistas) or Greek Gentiles (hellenas) was so successful that Jerusalem sent Barnabas to assist in the work. Barnabas went to Tarsus to get Saul’s help. Both of them then labored at Antioch for a year as teachers. Antioch became famous as the home church of Paul and as the place where believers were first called Christians. Later the church in Antioch sent Barnabas and Saul with a financial gift to the needy saints at Jerusalem.

12:1–25

About this time Herod Agrippa I killed the apostle James and imprisoned Peter. In response to prayer, Peter was released by an angel, contacted his praying friends, and then left the area (12:17). For his action Herod was judged by God with disease and death.

13:1–13

These next two chapters (chs. 13–14) contain the record of the first missionary journey of Paul and Barnabas in which the first serious attempt to reach Gentiles was made. It began with a specific call by the Holy Spirit to the ministering prophets and teachers at Antioch in Syria: "Separate me Barnabas and Saul for the work whereunto I have called them" (13:2). These leaders recognized the divine call and sent the two away with their blessing. Accompanied by John Mark, they sailed from the Syrian seaport of Seleucia to the city of Salamis on the island of Cyprus. After preaching in the synagogue, they traversed the length of the island, arriving at Paphos where Paul afflicted Elymas with blindness for the latter’s opposition to the gospel message. When they left Cyprus for the south central section of modern Turkey, John Mark defected and returned to Jerusalem. Why did he do this? Perhaps the rigors of the travels were too much for him especially since he had no direct call; maybe his Jewish heritage reacted against the ministry to the Gentiles; or he may not have liked the increasing leadership strength exercised by Paul over his uncle Barnabas.

Antioch of Syria, the home base for Paul’s missionary journeys. Its church sent delegates to the Jerusalem conference recorded in Acts.

A section of the Roman aqueduct that carried water to Pisidian Antioch. This city served as a center of civil and military affairs for the southern part of the province of Galatia.

13:14–49

At Antioch in Pisidia Paul delivered a typical sermon that he would preach in a synagogue to both Jews and Gentile proselytes (13:16, 26, 43). In developing the past history of Israel, he referred to the messianic hope promised through Abraham and David; then he proceeded to prove how Jesus fulfilled those prophecies in His life, death, and resurrection. His conclusion and invitation emphasized salvation by grace: "… through this man is preached unto you the forgiveness of sins: and by him all that believe are justified from all things, from which ye could not be justified by the law of Moses" (13:38–39). When Jewish hostility forced him out of the synagogue, Paul extended his ministry to the Gentiles of that region (13:45–49).

13:50–14:28

Forced to leave Antioch, they went to Iconium, preached and performed miracles, and were driven out by the combined efforts of the Jews, Gentiles, and rulers. At Lystra, after healing a cripple, Paul disavowed the worship of the idolatrous pagans by pointing them to the living God through the testimony of general revelation in nature. After being stoned almost to death, Paul continued on to Derbe. On their return trip through the same cities they had evangelized earlier, they instructed, comforted, and trained the converts to carry on an indigenous work in their absence. When they returned to Antioch in Syria for their first "missionary furlough" they explained how God "had opened the door of faith unto the Gentiles" (14:27).

15:1–35

The first doctrinal controversy in the early church centered on the necessity of circumcision for personal salvation. To settle the issue, a council was convened in Jerusalem. After major addresses by Peter, Paul, Barnabas, and James, the council decided that a Gentile convert did not have to be circumcised in order to have the same salvation possessed by a circumcised, Jewish Christian. In letters to the Gentile churches, they recorded their verdict; however, they did request that the Gentiles watch their diet and behavior for reasons of testimony to the Jews in their respective areas. Paul and Barnabas then returned to Antioch, accompanied by Silas.

15:36–41

Paul’s second missionary journey (15:36–18:22) was conceived in this request of Barnabas: "Let us go again and visit our brethren in every city where we have preached the word of the Lord, and see how they do" (15:36). When they argued over the advisability of taking John Mark once again, Barnabas took him and sailed for Cyprus whereas Paul chose Silas and followed the land route into Syria and Cilicia. Since Paul had the recommendation of the church, he must have been right and Barnabas wrong. The latter’s recorded ministry ends with this action.

16:1–40

After Timothy joined the team at Lystra, they advanced through the regions of Phrygia and Galatia to the Aegean port of Troas, having been forbidden of the Spirit to preach in the provinces of Asia and Bithynia. In a vision Paul was directed to go into the European region of Macedonia. Luke then joined the team and all four went to Philippi. After some initial preaching and the unjust imprisonment and beating of Paul and Silas, a small nucleus of believers was established, meeting in the house of Lydia, the first convert in Europe.

17:1–34

Having left Luke in Philippi, the team traveled to Thessalonica where they labored for about a month. After a successful ministry, they were forced to leave when unbelieving Jews misrepresented them before the Gentile rulers of the city. The Thessalonian Jews followed Paul to Berea and pressured him out of this city also. The Berean brethren took Paul to Athens, and after their return, informed Silas and Timothy to join Paul in that city. Meanwhile, Paul preached both in the synagogue and on Mars’ Hill before the pagan philosophers. In the condensed sermon recorded here, Paul declared that the unknown God whom they ignorantly worshiped had revealed Himself not only through nature but personally through Jesus Christ in His life, death, and resurrection. A few converts were won through his ministry there.

18:1–22

Paul’s partners apparently joined him at Athens and were subsequently sent back to Macedonia (18:5; cf. 1 Thess. 3:1–6). Paul moved on to Corinth where he labored for eighteen months (18:11). At first, he worked as a tentmaker with Aquila and Priscilla to support himself and to maintain a reproach-free testimony (cf. 1 Cor. 9:1–18). Later he devoted all of his energy to a major ministry among Gentiles in spite of strong opposition. Paul and his team then returned to Antioch after short stops at Ephesus, Caesarea, and Jerusalem.

18:23–19:41

The third journey (18:23–21:17) began as an edification ministry in Galatia and Phrygia. Paul then went to the key city of the province of Asia, Ephesus, where he labored for three years, longer than in any other city (19:8, 10; 20:31). The first converts there were disciples of John the Baptist, won to that position by Apollos who subsequently became a Christian through the witness of Aquila and Priscilla. He preached in the synagogue for three months, separated the converts, and continued for two years in the school of Tyrannus. From this strategic spot all inhabitants of Asia heard the word. Many believe that the famous seven churches of Revelation (chs. 2–3) were started as a result of Paul’s ministry in Ephesus. Many occultists were saved through Paul’s ministry of healing and casting out of demons. There were so many converts that the "idol-making" industry began to suffer financially. The silversmiths, in their frustration, tried to rally the city behind their cause, but were unsuccessful.

20:1–21:17

Paul then revisited the churches of Macedonia and Greece that were founded during the second journey. He decided to return to Antioch via Macedonia and Asia. Several journeyed with him from Philippi to Troas, including Luke who was destined to accompany Paul from then on. A quick stop at Miletus enabled Paul to encourage the elders of Ephesus and to warn them against the rise of false teachers both from within and without the church. They then sailed for Caesarea with short stops at Coos, Rhodes, Patara, Tyre, and Ptolemais. Both at Tyre and Caesarea Paul was warned by believers speaking by the Holy Spirit not to go to Jerusalem. Many have debated whether Paul disobeyed the will of God by discounting this counsel and by going to Jerusalem. It is difficult to say whether Paul was right or wrong in his decision to do so.

21:18–22:30

To repudiate the false rumors about his ministry to Jews of the dispersion, Paul agreed for the sake of testimony to purify himself ceremonially and to offer a sacrifice in the temple. When unsaved Jews of Asia (probably from Ephesus) saw him there, they falsely accused Paul of bringing a Gentile into the Jewish section of the temple. The Jews reacted by trying to kill him, but Paul was rescued and later bound by Roman soldiers. After explaining to the chief captain who he was, Paul was given opportunity to address the Jewish multitude. In his defense, or apology, Paul reiterated his conversion experience and call into the ministry. When he claimed that the resurrected Christ had commissioned him to preach to the Gentiles (22:21–22), the multitude became enraged. Paul was then taken into the castle and bound over for future investigation.

Roman street and arch at Tyre

The fortress of Antonia, as duplicated in the model of Herodian Jerusalem. The fortress was adjacent to the temple area. Roman troops were dispatched from here to rescue Paul from the mob.

23:1–24:27

The next day Paul stood before the same religious council that "tried" Christ. He used psychology by identifying himself with the Pharisaical sect as over against the Sadducees. Such a fierce debate erupted that the Romans again removed him to the castle. When the soldiers heard of the plot to kill Paul, they transported him under heavy guard to the Roman governor Felix at Caesarea. About five days later, when the Jews brought formal charges against Paul, the apostle so ably defended himself that Felix delayed action on the case. For the next two years Paul was interned at Caesarea. Although he heard Paul expound the gospel on several occasions, Felix refused to release him for two reasons: a desire to receive bribery money and a determination to please the Jews.

25:1–26:32

When Festus replaced Felix, he offered Paul a chance to be tried in Jerusalem, but Paul refused and asked to be tried by Caesar (his right as a Roman citizen). When Herod Agrippa II visited Festus, Paul was granted the opportunity to voice his defense before both of them. Again he centered his apology in his conversion experience at which time he saw the resurrected Christ and was commissioned by Him. Festus thought Paul was insane, but Agrippa wondered about the truth of the apostle’s message. Both agreed that Paul was innocent and that he would have been released if he had not appealed to Caesar.

27:1–28:10

The voyage to Rome was marked by delay and difficulty. They sailed to Sidon, near Cyprus, on to Myra, and stopped at Crete. Against Paul’s advice, the ship set sail and encountered a fierce storm. When the sailors and soldiers gave up hope of deliverance, Paul assured them that all lives would be spared. The ship finally wrecked near the island of Malta where Paul was delivered from the death of a poisonous snake bite by God. Paul then engaged in a ministry of healing on the island.

28:11–31

Three months later they sailed again, stopping at Syracuse, Rhegium, and Puteoli. By land they then went to Rome where Paul underwent a special imprisonment (28:16). After Paul called for the Jewish leaders of Rome, he explained his imprisonment and declared the gospel to them. The book ends with a note about Paul’s two years of house arrest in Rome with complete freedom to receive visitors and to proclaim the gospel.

St. Paul’s Bay in Malta where Paul suffered shipwreck. On the large islet on the left, a statue of Paul commemorates the event of Acts 27.