9

ROMANS

Writer

What can be said about this amazing life?! Almost the entire history of the apostolic church (Acts 9–28) can be equated with the personal history of Paul, the greatest of the apostles. He was born and raised in Tarsus, the chief city of Cilicia and one of the great learning centers of the Eastern World. Because his parents were Jews who possessed Roman citizenship, he inherited a unique status: he was both a Roman and a Jew. His Jewish heritage was flawless: "Circumcised the eighth day, of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, an Hebrew of the Hebrews" (Phil. 3:5). He was doubtless named "Saul" after the first king of united Israel. Most Romans had purchased their rights of citizenship, but Paul was born into his (Acts 22:25–29). Some believe that the Graeco-Roman name "Paul" was given to him by his parents because of the double world into which he was born. However, most evangelicals claim that Saul took the name "Paul" after his conversion, possibly after winning his first Gentile on his initial missionary journey, Sergius Paulus (Acts 13:7–12). Was it coincidental that Luke recorded the change of his name in the midst of the narrative account of the salvation experience of this Roman deputy?

Typical of Jewish male children, he learned a manual trade, tent-making (Acts 18:3). Probably at the age of thirteen, he was sent by his wealthy, Pharisaical father (Acts 23:6) to study in Jerusalem under the learned and respected Gamaliel, also a Pharisee and a doctor of the law (Acts 22:3; cf. 5:34–39). In those training years he "profited in the Jews’ religion above many my equals in mine own nation, being more exceedingly zealous of the traditions of my fathers" (Gal. 1:14). Within his peer group he showed the most promise of becoming an outstanding Pharisee.

Ruins of the ancient city wall of Tarsus.

He is first mentioned in Scripture as the young man in charge of the robes of those who stoned Stephen (Acts 7:58). From that point on he became a fanatical persecutor of Christians, both imprisoning them and putting them to death (Acts 22:4; 26:10–11; Gal. 1:13). Christians everywhere were deathly afraid of him (Acts 9:13, 26). Based upon attitudes and actions, Saul of Tarsus must have been considered the most unlikely candidate for salvation, and yet God sovereignly saved him when Jesus Christ manifested Himself to him on the road to Damascus (1 Tim. 1:12–16; cf. Acts 9:1–16; Gal. 1:11–15; about a.d. 32). Through this supernatural revelation and others, Paul became both a witness of the resurrected Christ and a commissioned apostle (Acts 9:15–16; Gal. 1:11–12; 1 Cor. 15:8–10).

His early years of witness were spent mainly in Syria, Arabia, and Judea (a.d. 32–35; Acts 9:19–29; Gal. 1:17–21). He then went into relative seclusion at his hometown of Tarsus for about nine years (a.d. 35–44; Acts 9:30). Barnabas brought him from Tarsus to Antioch in Syria to work in that growing church as a teacher (a.d. 44–47; Acts 11:25–30; 12:25). Antioch then became the home base for his three famous missionary journeys. The following chart will reveal the scope of those ventures:

During the interval between the first and second journeys, Paul probably wrote Galatians and engaged in the deliberations of the council at Jerusalem (Acts 15).

At Jerusalem Paul was arrested and imprisoned, not only there but also at Caesarea for two years (a.d. 56–58; Acts 21:18–26:32; cf. 24:27). After a treacherous voyage, Paul arrived at Rome where he remained a prisoner for two more years (a.d. 58–61; Acts 27:1–28:31; cf. 28:30), during which time he wrote Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, and Philemon. Although Scripture is silent on the subject, Paul was apparently released, enabling him to resume a limited itinerary, including Crete, Ephesus, and Macedonia (a.d. 61–64; 1 Tim. 1:3; Titus 1:5). During this freedom, he penned I Timothy and Titus. When the imperial persecution against Christianity began under Nero, Paul was arrested and taken to Rome where he was again imprisoned (a.d. 64–67). His last book, II Timothy, reflected his expectation of imminent martyrdom. Tradition states that he was beheaded about a.d. 67 in Rome and that his corpse was buried in subterranean labyrinths underneath the city.

Although critics have doubted the Pauline authorship of many of his Epistles, the Book of Romans has been accepted even by them as one of his genuine letters. Early Church Fathers, including Ignatius, Justin Martyr, Polycarp, Hippolytus, Marcion, and Irenaeus, definitely recognized the book as canonical and as written by the apostle. Internal evidence supports their judgment. The author claimed to be Paul (1:1). He regarded himself as a special apostle to the Gentiles (1:1; 11:13; 15:15–20; cf. Acts 9:15; Gal. 2:8). He was a Jew (9:3, 4). He was a pioneer missionary, laboring in untouched fields (15:15–20; cf. Acts 13–20). He planned to take a financial contribution to the poor at Jerusalem (15:25–26; cf. Acts 24:17; 1 Cor. 16:1–3; 2 Cor. 8–9). His apprehension over visiting Jerusalem corresponds with his fears expressed elsewhere (15:30–31; cf. Acts 20:22–23). His expressed purpose to visit the Roman church was also pointed out by his chronicler, Luke (1:10–15; 15:23–24; cf. Acts 19:21). This data in Romans can be found in other parts of Paul’s letters and personal history. There can be no doubt that the author of this Epistle is none other than Paul the apostle.

City of Rome

The founding of the city in 753 b.c. is based more upon fanciful myth than objective history. Tradition states that it was started by Romulus, a son of Mars, who was preserved physically both by a wolf and a shepherd’s wife after he was forced out of his house by wicked relatives. He became its first king and thus began that early monarchy. Later the city was named after him.

The city was located on swampy ground beside the Tiber, a river in Italy that flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The city itself was about fifteen miles from the sea. Over several years many hills or mounts were constructed and settled so that it came to be known as the "city of seven hills." These hills bear the following names: Palatine, Capitoline, Quirinal, Caelian, Aventine, Esquiline, and Viminal. Later these hills were enclosed by a stone wall.

By New Testament times the city had grown to a population well over a million (some have placed it as high as four million), the majority of which were slaves. As the center of the Roman empire, it attracted all kinds of people and religions. There were an estimated 420 temples there, dedicated not only to the gods of the Romans but also to the gods of the people that the Romans had conquered. The wealth of the city could also be seen in the magnificent buildings constructed throughout its borders. There was even a sizeable colony of Jews in Rome, probably brought there through the Palestinian conquests of Pompey.

Time and Place

When Paul wrote Romans, he was about to go to Jerusalem with the contribution of the Greek churches for the poor saints in the holy city (15:25–26). This means that he must have written this letter after the two Corinthian Epistles. Near the end of his three-year ministry at Ephesus during his third journey, he wrote First Corinthians in which he gave instructions for the collection (1 Cor. 16:1–9). When he left Ephesus, he went into Macedonia (Acts 20:1; 1 Cor. 16:5). He apparently wrote Second Corinthians at this time because he informed the Corinthian church that he was bringing Macedonians with him and that he did not want the church to be unprepared at their arrival (2 Cor. 9:1–5). Paul then moved from Macedonia into Greece or Achaia, the province in which Corinth was located, where he stayed for three months (Acts 20:1–3). Since his original purpose was to sail from Greece for Jerusalem via Syria (Acts 20:3), it must be that Paul wrote Romans during his brief stay at Corinth, probably about a.d. 55–56. This position is further supported by the fact that Paul commended to the Roman church Phebe, a deaconess in the church at Cenchrea, the seaport of Corinth (16:1–2). Since she is mentioned first in this long chapter of names, Phebe probably carried the letter from Paul to Rome. Paul also wrote: "Gaius mine host, and of the whole church, saluteth you. Erastus the chamberlain of the city saluteth you" (16:23). Since Gaius was a Corinthian convert (1 Cor. 1:14) and since Erastus is later mentioned as a Corinthian inhabitant (2 Tim. 4:20), Paul must have been in Corinth at the time of writing.

The Appian Way, near Rome.

There is an alternate theory that suggests the place to be Philippi shortly before Paul sailed for Troas (Acts 20:5–6). It is true that Paul had to abandon his plans of sailing from Greece because of a Jewish plot against his life and that he subsequently returned to Macedonia before departing for Asia Minor and Jerusalem (Acts 20:3–4). However, his plan to go to Jerusalem fits more into his intended purpose to sail from Greece rather than into a pressured unintended change of plans. Also, the way in which he refers to the Greek collection ("… of Macedonia and Achaia"; 15:26) implies that he was in Achaia at the time of writing, otherwise he would have reversed the order. The mention of Illyricum (15:19) does not mean that Paul had to be in the adjacent section of Macedonia at the time of writing; it only signified to the Roman church that he had gone as far north in his evangelism as he planned and that he now wanted to move westward toward Rome and Spain. Although the Philippi theory has a plausible ring to it, the traditional view of Corinth fits best into the existing evidence.

Purposes

If Galatians has been called the Magna Charta of freedom from legalism, then Romans must be regarded as the Constitution of Biblical Christianity. It was not designed as a tract for sinners, but as a doctrinal treatise to expound the complexities of the faith. These two verses (1:16–17) give the gist or essence of Paul’s theme:

For I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ: for it is the power of God unto salvation to everyone that believeth; to the Jew first, and also to the Greek. For therein is the righteousness of God revealed from faith to faith: as it is written, The just shall live by faith.

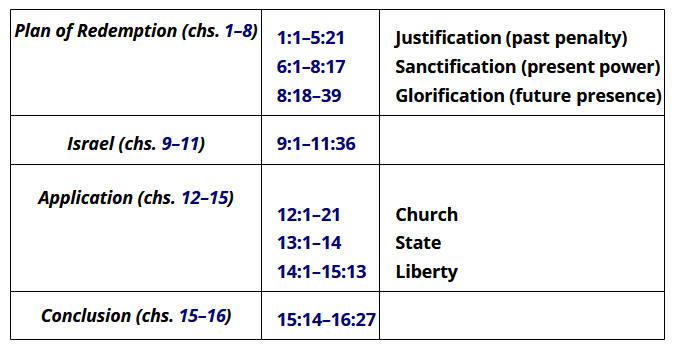

The righteousness of God, as revealed in the gospel message, is based upon the faith principle from the beginning to the end. Sinners are not only saved or justified by faith in Christ, but justified men must also walk daily by faith. In his exposition Paul deals with the great doctrinal words of the evangelical Christian faith: gospel, resurrection, salvation, belief, faith, righteousness, wrath, judgment, repentance, sin, law, guilt, justification, redemption, propitiation, grace, imputation, peace, reconciliation, atonement, death, sanctification, adoption, glorification, hope, election, foreknowledge, predestination, and purpose. The following chart shows how Paul developed his general theme:

The first eight chapters manifest God’s magnificent plan of redemption. First, Paul shows how a lost, guilty man can receive the righteousness of Christ, be given a justified standing before God, and thus forever be delivered from the penalty of sin. Then he reveals how a saved man can gain the sanctified life or victory over the power of the indwelling sin nature through the enabling ministry of the Holy Spirit. Finally, he demonstrates how the believer will eventually be delivered from the presence of sin through the change of his mortal, corruptible body into a glorified state.

A second general purpose in writing was to explain how the present plan of God in blessing mostly Gentiles could be harmonized with the unconditional covenant promises given to Israel. How could the Gentiles be absolutely sure that God would complete His announced program for them when He had not yet fulfilled the promises given to ancient Israel? Paul undertakes to answer this critical question in the second section (chs. 9–11).

Positional truth must be put into practice; therefore, Paul ended his teaching by showing how the righteousness of God could be applied to the daily walk of the believer. His triple thrust included the Christian’s relationship to other Christians in the life of the local church (12:1–21), his attitudes toward the unsaved, especially government leaders, within society (13:1–14) and his deportment in those areas not specifically spelled out in Scripture (14:1–15:13).

Paul also wanted to inform the Roman Christians of his future plans to visit them after his trip of benevolence to Jerusalem was over (1:10–12; 15:22–32). Apparently he had tried to visit Rome several times before, but he had been prevented from doing so (1:13; 15:22).

In his closing remarks it was his desire to commend Phebe, his lady ambassador to Rome (16:1–2), and to send greetings to many of his spiritual acquaintances residing in Rome (16:3–16).

Some have wondered why Paul wrote such a lengthy letter to a church that he planned to visit in the near future. However, his Corinthian correspondence also was sent prior to a visit, involving an interval of time much shorter than that between the letter to the Romans and his trip to Rome. Actually, Paul was laying the groundwork for the western expansion of the gospel by establishing rapport with this strategic church. Perhaps he hoped that the Roman church would finance his proposed evangelization of Spain ("Whensoever I take my journey into Spain, I will come to you … and to be brought on my way thitherward by you" (15:24). Paul did have some apprehension over his reception in Jerusalem (15:31), knowing full well that his plans to go to Rome could be delayed indefinitely. Actually, this did occur, and he arrived at Rome as a prisoner some three years later. Since Rome was on the western edge of missionary expansion and had not yet had the benefit of direct apostolic teaching, either in oral or written form, there was a need for him to write in depth.

Distinctive Features

The Epistles are unique pieces of ancient literature. In the secular world of the New Testament era, the average letter contained about 1300 words, whereas the Epistles contained many more. The Pauline range extends from 335 words in Philemon to 7101 words in Romans. Thus, Romans is the longest of Paul’s Epistles.

In fact, most of the New Testament books (twenty-one) are Epistles. In one sense, Revelation could even be classified among them since it was sent to the seven churches of Asia and includes seven "mini-letters" within the body of the text. This takes on significance when one realizes that there are no epistles found within the Old Testament canon.

The composition and sending of an epistle usually involved four people: author, secretary or amanuensis, messenger-mailman, and recipient. Because of his poor eyesight (Gal. 4:13–15; 6:11), Paul probably used amanuenses on several occasions. In all of his letters, he would write personally the closing lines in order to authenticate the contents of the book (1 Cor. 16:21; Col. 4:18; 2 Thess. 3:17; Philem. v. 19). Some believe that Paul wrote the entire Book of Galatians under much physical hardship to himself, but others still contend that he wrote only the conclusion (Gal. 6:11–18). Tertius was the secretary employed for Romans (16:22); Peter used Silvanus for the composition of his First Epistle (1 Peter 5:12).

The Book of Romans provides an excellent model for studying Paul’s literary style. Usually his Epistles follow this format: an opening greeting or salutation, followed by a prayer of thanksgiving for the readers; an exposition of doctrinal truth, followed by specific applications to the lives of the readers; a conclusion with greetings, personal messages, and a bequest of grace.

The use of the first person plural pronouns (we, us, our) has stimulated some speculation. Did Paul use the editorial "we" in reference to only himself or did he include his associates (e.g., Silas, Luke) or did he refer to himself and to the amanuensis? Actually, one cannot have a firm opinion here because each use must be studied within its own context.

Christians should know where to find key doctrinal chapters or passages in the Scriptures, and Romans is a treasure house of those: the lost state of the heathen who have rejected and perverted the general revelation of God in nature (1:18–32); the faulty condition of man’s conscience as a moral guide (2:1–16); total depravity, or the guilty standing of all sinners (3:9–20, 23); man’s moral relationship to Adam (5:12–21); the believer’s identification with Jesus Christ in His death and resurrection (6:1–11); the struggle of the two natures in the life of a Christian (7:7–25); the plan of redemption (8:28–39); the explanation of Israel’s unbelief (9:1–11:36); the necessity of dedication (12:1–2); the relationship of the believer to government (13:1–7); and the principles of Christian liberty (14:1–15:3).

It should also be observed that Romans makes great use of the Old Testament. Paul initially declares that the gospel of God concerning the person and redemptive work of Christ was "promised afore by his prophets in the holy scriptures" (1:2). Of all the Old Testament quotations in Paul’s writings, more than half of them are found in this book. No one could accuse Paul of destroying either the law or the prophets.

Unity of the Epistle

Some critics have attacked the integrity or unity of this Epistle by stating that all or parts of the last two chapters were not written by Paul and thus were not part of the original letter. According to them, there is no strong indication as to who made the addition or when it was done. This view is highly speculative. Actually, the content of 15:1–13 is necessary as a fitting conclusion to the principles of liberty deliberated earlier (14:1–23). Also, Paul’s travel plans (15:14–33) correspond to other authoritative passages (Acts 19:21; 24:17; 1 Cor. 16:1–4; 2 Cor. 8–9). About three hundred extant Greek manuscripts of Romans include these chapters as part of the whole. There is no objective, manuscript proof for this theory of addition.

A slight abridgement of this critical view states that the closing chapter actually formed a part of a letter commending Phebe to the Ephesian church. Since it is known that Paul spent three years at Ephesus and that Aquila and Priscilla were pillars in that church (Acts 18:18–19, 24–27; cf. Rom. 16:3–5), they argue that Paul must have sent Phebe to Ephesus. The argument asks, how could Paul know so many people in Rome when he had not yet visited that city? However, it must be remembered that Aquila and Priscilla were originally from Rome and that they were forced to leave because of Claudius’ decree (Acts 18:2). It is very likely that they returned to Rome after the death of Claudius and after their work in Corinth and Ephesus was over. Perhaps they went to Rome in anticipation of Paul’s proposed trip to the capital. Since Paul traveled frequently among the churches and kept in constant communication with them, he would have known whether any of his friends and/or converts had gone to Rome. Thus, it would have been very natural to greet them.

Establishment of the Church

At the time Paul wrote, the church at Rome must have been in existence for some time. The fact that he had a desire for many years to visit it would confirm that statement (1:13; 15:23). Since the faith of the Roman Christians was "spoken of throughout the whole world" (1:8), years would have been needed to accomplish that outreach. Some have suggested that believers were among those Jews expelled from Rome by Claudius (a.d. 49; Acts 18:2). An early tradition states that they were driven out over rioting caused by a certain "Chrestus." Does this name refer to an unidentified Roman or to Jesus Christ? The latter is a distinct possibility.

The church was composed mainly of Gentile converts with a modest sprinkling of Jewish saints. The greeting list included Jewish, Roman, and Greek names (16:3–15). Paul clearly wrote: "For I speak to you Gentiles, inasmuch as I am the apostle of the Gentiles" (11:13). Other statements imply a large Gentile membership (1:5, 6, 13; 15:5, 6, 16, 18). He referred to the Jews as "my brethren, my kinsmen" (9:3), not as ours, which would have been the case if the readers were mostly Jewish. However, he does seemingly identify himself with some of his readers as being mutually Jewish (2:16–17; cf. 3:9; 4:1).

Although the real origin of this church is basically unknown, four strong possibilities have been suggested. The first is that Roman pilgrims, both Jews and Gentile proselytes, who were converted under Peter’s preaching on the day of Pentecost returned to their city and founded the church (Acts 2:10). The second is that Aquila and Priscilla, upon their return to Rome, started the work through lay evangelism (Acts 18:2; cf. Rom. 16:3–5). The official position of the Roman Catholic Church is that the apostle Peter traveled to Rome and established the church there during a lengthy ministry, perhaps twenty years or more. The fourth view is that the converts of Paul from Asia Minor and Greece won during his three journeys moved to Rome and congregated themselves into a local church because of their common faith.

This last view seems to be the most plausible for the following reasons. During the years a.d. 30–44, Peter’s activities were confined mainly to Jews in Palestine (Acts 1–12). When Paul wrote Galatians (a.d. 48–49), it was generally recognized that God had called him to a ministry among the Gentiles and that Peter’s labor was to the Jews (Gal. 2:7–9). On several occasions Peter was reluctant to associate himself with Gentiles (Acts 10; Gal. 2:11–14). Since the Roman church was predominantly Gentile, it would have been contrary to Peter’s character and to his God-given sphere of ministry for him to have started it.

On the positive side, Paul openly declared his intention not to build on another man’s foundation (Rom. 15:20). Now, if Peter or any other apostle had founded the Roman church, then why did Paul want to go to Rome? He stated: "For I long to see you, that I may impart unto you some spiritual gift, to the end ye may be established" (1:11). Why did Paul feel that he could give them something that Peter or any others could not? Did he believe that they had done a faulty or partial job? The only logical reason for his going was that his converts, so greeted by name (ch. 16), had founded the work and therefore he was the spiritual grandfather of the church. Since the church had never benefited from the direct, personal ministry of an apostle, he felt compelled to go.

When Paul greeted the Roman believers (Rom. 16), why did he omit Peter’s name if the latter were there (a.d. 55–56)? Later, in the record of Paul arriving in Rome and staying for at least two years (a.d. 59–61), there is no mention that Peter was there. In the four Prison Epistles written at this time, Paul again did not refer to Peter. When Paul wrote II Timothy from Rome just before his martyrdom (a.d. 64–67), Peter’s name is conspicuous by its absence. All of this inductive study adds up to the conclusion that the church was started indirectly by Paul through his converts.

Outline

Salutation and Theme (1:1–17)

I. Justification (1:18–5:21)

A. Its need (1:18–3:20)

1. The guilt of the heathen (1:18–32)

2. The guilt of the moralist (2:1–16)

3. The guilt of the Jew (2:17–3:8)

4. The guilt of the entire human race (3:9–20)

B. Its provision (3:21–26)

C. Its relationship to the law (3:27–31)

D. Its illustrations (4:1–25)

E. Its security (5:1–11)

F. Its universal nature (5:12–21)

II. Sanctification (6:1–8:17)

A. Its basis (6:1–14)

B. Its principle (6:15–23)

C. Its new relationship (7:1–25)

D. Its power (8:1–17)

III. Glorification (8:18–39)

A. Relationship to human sufferings (8:18–27)

B. Relationship to divine purpose (8:28–39)

IV. Israel’s Divine Purpose (9:1–11:36)

A. Paul’s concern for Israel (9:1–5)

B. Her relationship to divine promise (9:6–13)

C. Her relationship to divine justice (9:14–29)

D. Her relationship to divine righteousness (9:30–10:21)

E. Her relationship to divine election (11:1–10)

F. Her relationship to Gentile blessing (11:11–22)

G. Her future salvation (11:23–32)

H. Paul’s praise of divine wisdom (11:33–36)

V. Application of Righteousness (12:1–15:13)

A. In the dedication of life (12:1–2)

B. In the church (12:3–21)

C. In the state (13:1–7)

D. In society (13:8–14)

E. In nonmoral issues (14:1–15:13)

VI. Conclusion (15:14–16:27)

A. Paul’s future plans (15:14–33)

B. Paul’s greetings (16:1–16)

C. Paul’s warning (16:17–27)

Survey

1:1–13

In his opening remarks, Paul identified himself in three ways: a servant, an apostle, and one separated unto the gospel. He declared that the gospel was promised in the Old Testament and that its message centered in the two natures of Jesus Christ as proven by His incarnation and resurrection. After greeting the Roman believers, Paul gave thanks for the universal testimony of their faith and revealed his desire to visit them.

1:14–17

The missionary heart of Paul can be seen in the famous three "I am’s": "I am debtor … I am ready … I am not ashamed.…" He saw himself under moral obligation to proclaim the gospel to all classes of men. The cause-effect sequence of his motivation is revealed by the fourfold use of "for." Why was Paul ready to preach? For he was not ashamed of the gospel. Why was he not ashamed? For it is the power of God unto salvation. Why does it provide salvation? For in it the righteousness of God, received and nurtured by faith, is revealed. Why must the righteousness of God be received by faith? For all men stand condemned beneath the wrath of God.

1:18–32

In this next section (1:18–3:20), Paul demonstrated why the entire world is guilty before God. It is because all men have rejected some form of divine revelation. God’s existence, power, intelligence, and deity can be known through nature (1:18–20; cf. Ps. 19:1), but unsaved men held down the truth in unrighteousness, did not glorify God, were not thankful, became foolish, became idolatrous, and worshiped the creature instead of the creator. For this perversion they are without excuse. Divine retribution is seen in the thrice mention of "God gave them up" (1:24, 26, 28). Their hardened spiritual condition is illustrated in the closing verse of this section: "Who knowing the judgment of God, that they which commit such things are worthy of death, not only do the same, but have pleasure in them that do them."

2:1–16

The pagan moralist who criticizes the animistic heathen is just as guilty because he has rejected divine truth found in the image of God within himself. All men are moral personalities with an innate sense of oughtness, a sense of right and wrong as exhibited by the conscience. However, when they violate the moral law within their hearts, they blame their heredity or environment or rationalize their actions instead of repenting (2:15). These men will be divinely judged, without partiality, according to truth, their works, and the gospel (2:2, 6, 11, 16).

2:17–3:20

The Jew, who had the advantage of his religious and physical heritage plus the presence of oral and written divine revelation, is nevertheless no better in the sight of God because he likewise rejected His revelation. Thus, Paul proved "both Jews and Gentiles, that they are all under sin" (3:9). All men therefore are equal before God, equally guilty. They are all under the penalty, power, and presence of sin. Mankind is totally depraved. This means that all are as bad off as they can be, not that they are as bad as they can be. When men admit their guilt and inability to correct their spiritual condition, they are in a position to receive God’s provision of righteousness.

3:21–31

Paul then argued that the reception of divine righteousness apart from human effort was even proved by the Old Testament (Gen. 15:6; Hab. 2:4). It can be received today through faith in Jesus Christ. This plan of salvation is for all men (heathen, Gentile, Jew) because all men are sinners and equally needy; God does not have two or three different plans to save different classes of men. It was because of Christ’s redemptive death and resurrection, once anticipated but now fulfilled, that God could forgive sin and impute divine righteousness even in Old Testament times. God never gave the law that men might try to keep it and thereby gain eternal life; it was designed to reveal to men how sinful they were and how holy God was. When men saw that they were condemned by a broken law and cast themselves in faith upon a gracious, merciful God, then the purpose of the law was established in their lives.

4:1–25

To show that men have always been justified, or declared righteous, by faith, Paul selected two Old Testament characters. Abraham received the righteousness of God and the covenant promises on the basis of faith alone before the rite of circumcision was imposed upon him and before the law was given to Israel. Even after the law was given, David was justified by faith only. No works or law keeping has ever been added to the faith principle. Today, by faith only, men can receive God’s righteousness "if we believe on him that raised up Jesus our Lord from the dead; who was delivered for our offences, and was raised again for our justification" (4:24–25).

5:1–11

Through justification by faith, a believer has an unalterable standing before God. He can rejoice in the fact that if God did so much for him when he was an ungodly sinner, He will do "much more" (5:9, 10) now that he is one of His children. Note the position enjoyed by every Christian: he is justified by faith, has peace with God, is standing in grace, experiences the presence of the love of God and the Holy Spirit in his heart, benefits from Christ’s vicarious death, is justified by His blood, shall be saved from wrath through His resurrection life, is reconciled, and receives the Atonement.

5:12–21

Sin and death entered the world through Adam. All men spiritually lost are in Adam and are therefore condemned to both physical and spiritual death. Paul then contrasted this with the believer’s position in Christ. In Christ one has the free gift of grace, justification, life, and righteousness. Men today in their spiritual standing are either in Adam, condemned, or in Christ, justified.

Having established how a guilty sinner could receive a justified standing before God, Paul then wanted his readers to know how they could put into daily practice their new position in Christ. Many believers who have been delivered from the penalty of sin have never enjoyed victory over the power of the indwelling sin nature or the sanctified life. To sanctify means to set apart. Initial sanctification is the act of God whereby He sets apart permanently the believing sinner from the world unto Himself (cf. 1 Cor. 1:2; 6:11; Heb. 10:14). This act entitles the believer to be called a saint, or a separated one. His need now is progressive sanctification, the process by which he can be set apart from a sinful walk to a holy practice.

6:1–23

The problem that Paul dealt with in this next section (6:1–8:17) was: How can a saint become saintly? A secure spiritual standing should never issue in sinful license. Believers should know that they have been identified with Jesus Christ in His death and resurrection (cf. Gal. 2:20). When He died, they died in Him; when He arose, they arose in Him. Just as sin and death no longer have dominion over Him, neither do they over the believer. The Christian should believe to be true what is true (meaning of "reckon"). He should reckon himself as dead to sin and alive unto God and should yield himself completely to his new spiritual master. Christ’s death not only removed the penalty of sin but also broke the power of the sin nature. Just as the believer was saved by faith in Christ’s provision, so he may believe that His death has already destroyed the power of the indwelling sin principle. Human effort did not bring him justification nor will it produce sanctification. Once he was a slave to sin; now he should be a slave to righteousness.

7:1–8:17

The believer is not only free from the dominion of sin, but he is also released from any obligation to the Mosaic law through his new relationship with Christ. There was nothing wrong with the law; in fact, it was holy, just, and good (7:12). The law created an awareness of sin and a sense of condemnation in the one who tried to keep it and failed. The problem was with man because in him there was no moral power to keep the law. This same dilemma exists in the life of the Christian who tries to please God daily in the energy of self; he only fails. Paul related this struggle between the two natures (old sin nature and new spiritual nature) from his own experience: "For the good that I would I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do" (7:19). In this passage (7:15–25) note the excessive use of the first person singular personal pronoun (I, me) and the total absence of any mention of the Holy Spirit. When Paul could not satisfy the desires of the new nature in his own strength, he despaired; but then he learned the secret of spiritual success. Such desires could be fulfilled through the power of the indwelling Holy Spirit (8:1–17); note the frequent mention of the Spirit in this section.

8:18–27

A believer can possess the justified standing and enjoy a sanctified state, and yet suffer in a body subject to disease and destined to death. Until he receives the glorified, immortal, incorruptible body at the coming of Christ, he has not yet been delivered from the total effects of sin in his life. Glorification is the future aspect of the divine gift of salvation to us. When Christ returns, even creation will be delivered from the curse imposed upon it because of Adam’s sin (Gen. 3:17–18; Isa. 11:1–9). Observe that the creation, the believer’s body, and the indwelling Holy Spirit all groan in anticipation of the deliverance from physical suffering (8:22, 23, 26).

8:28–39

Paul saw glorification as the logical climax of God’s eternal plan of redemption: foreknowledge, predestination, calling, justification, and glorification. The verbal tense of the phrase "them he also glorified" is very significant. Since God "calleth those things which be not as though they were" (4:17), He views man’s glorification as already accomplished because it is part of His unchanging decree, even though it is still future in time from man’s perspective. This was why Paul could confidently assert: "And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose" (8:28). Paul saw himself and all believers as constant objects of God’s will. In a series of five questions and answers (8:31–39), Paul relates the argument that the free gift of salvation could never be taken away from the Christian because of the eternal extent of God’s purpose, the fact that future sin cannot change the justified position of the believer, the reason that all condemnation has been removed through Christ’s death, and the assurance that the child of God can never be separated from the love of God. In a word, the Christian is eternally secure.

Many view the next three chapters as parenthetically inserted between chapters 8 and 12; however, there is a logical connection between this section and the preceding eight chapters. In it Paul is anticipating a possible objection: How can the Gentiles know that they can trust God for the completion of His program for them (justification, sanctification, glorification) when His covenant promises to Israel have not yet been fulfilled? This was a fair question, and Paul proposed to resolve the difficulty.

9:1–13

First of all, Paul identified himself as a Jew with an intense spiritual burden for his fellow Jews in spite of the fact that the latter constantly persecuted him. He then listed a ninefold description of the Jewish nation that elevated her in spiritual privileges above any other people. However, Paul quickly observed: "For they are not all Israel, which are of Israel" (9:6). A true Israelite was one who was not only a physical descendant of Abraham (child of the flesh) but one who was also a spiritual child of Abraham through faith in Christ (child of the promise). Paul argued that the covenant promises were given only to the elect children of Abraham, i.e., his physical and spiritual posterity. These promises have always been kept. God’s elective purposes were not determined by human choices, but by the divine will.

9:14–29

In the next few sections Paul carried on a rhetorical question-answer session with his readers. Throughout these paragraphs, he interrupted himself with questions introduced by phrases similar to this one: "What shall we say then?" (9:14; cf. 9:19, 30; 10:18, 19; 11:1, 7, 11, 19). First, he demonstrated that the sovereign actions of God were not unjust and were in perfect harmony with Old Testament declarations (9:14–18). God has a perfect right to do whatever He pleases because He is the Creator-God and man is His creature. Man has no right to question or to doubt His actions. His plan to set aside national Israel enabled Him to make Gentiles His "spiritual people" without violating the promises given to the elect remnant of Israel (9:19–29).

9:30–10:21

The reason why national Israel did not inherit the spiritual promises of the covenant was that she tried to gain the righteousness of God through works or human effort (9:32; 10:2–3). The righteousness demanded by the law can only be received through a believing confession in the deity and redemptive work of Jesus Christ (10:4, 8–10). In a logical sequence of questions (10:13–15), Paul showed that men cannot call on Christ for salvation unless someone tells them about Him because "faith cometh by hearing, and hearing by the word of God" (10:17).

11:1–36

The question and answer: "Hath God cast away his people?… God hath not cast away his people which he foreknew" (11:1–2) are very important. Just as God has not cast away His elect, foreknown covenant nation even though her history was full of sin and unbelief, so God will not cast away an individual believer whom He has foreknown (cf. 8:29). Future conduct does not nullify God’s unconditional promises and gifts. Even in the midst of this time of spiritual blessing upon Gentile peoples, there is a believing Jewish "remnant according to the election of grace" (11:1, 5). God sovereignly used the spiritual blindness of national Israel to accomplish the blessing of Gentiles (11:11), but one day Israel will again occupy the central position in God’s redemptive program for the world (natural branches to be grafted back into the olive tree). The blindness of Israel is only partial (some Jews today are being saved) and temporary (until God’s program for the church is completed; cf. 11:25). Then all Israel will be saved. In practice, the Jews of that generation were enemies, but in position, they were elect and beloved. Paul concluded: "For the gifts and calling of God are without repentance" (11:29). That means the eternal gift of salvation will never be taken back by God even though a believer may commit future sin. It also means that God will totally complete His program with Israel in spite of her present unfaithfulness. Paul ended this discourse on Israel by praising the wisdom of God for formulating such a gracious, intricate plan of redemption (11:33–36).

A relief of the seven-branched candlestick, from a synagogue of New Testament times.

12:1–2

The admonition (12:1–2) forms the bridge between the doctrinal chapters (1–11) and the practical chapters (12–16). Paul does not command; he beseeches. The connective "therefore" introduces a logical inference based upon the "mercies of God," the sovereign plan of God with its various gifts of salvation. The argument goes like this: If God has such an eternal, magnificent plan not only for individuals, but also for nations, then should not the believer yield himself completely to that God to run the daily details of his life? Only by so doing can he ever expect to know and to experience the will of God in his many involvements. If a Christian does not make this total dedication of life, then he will not be able to operate successfully in the areas mentioned in the next three chapters.

12:3–21

When a believer fully realizes that God was totally responsible for his salvation and commits his life to Him, then he will be in a frame of mind "not to think of himself more highly than he ought to think" (12:3). In the final analysis, all believers are sinners saved by divine grace. All believers are members of the spiritual body of Christ, the true church, and have been given differing functions to perform within that body. These functions are called gifts and are partially listed here: prophecy, ministry, teaching, exhortation, giving, ruling, and showing mercy. All believers in their relationships to one another in the body of Christ should manifest Christlike qualities in their deportment (12:9–21).

13:1–7

Since the power of government has been ordained of God and rulers have a ministry to perform for God, Paul charged that Christians should be obedient, submissive citizens. This passage elaborates upon Jesus’ declaration: "Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s" (Matt. 22:21). God established civil authority to be a terror or restraint to evil works, to punish evil doers, and to praise the good. As long as government operates in this realm, the believer must obey its dictates, not only to avoid punishment, but also to maintain a guiltless conscience for the sake of Christian testimony. This can be done by rendering tribute, custom, fear, and honor to those authorities who deserve it.

13:8–14

Believers also have responsibilities toward the unsaved within society. A person owes when he takes or borrows something without returning it; thus the Christian should not expect the world to give to him, but rather he should give to the world out of love. His testimony should be marked by spiritual alertness, moral purity, and an honest life. A Christ-filled life will not seek opportunities to gratify the desires of the sin nature.

14:1–12

Paul then gave guidelines as to how the justified person could apply the principles of righteousness to the area of Christian liberty. This deals with doubtful matters or nonmoral issues, those things which are neither forbidden in Scripture nor are morally impure in themselves. The attitudes in which they are done or not done and the effects caused by their doing do, however, involve moral choices. The problem at Rome dealt with the diet. Could a Christian eat meat taken from an animal that had been offered or dedicated to a pagan idol? Since the Roman believers differed on the issue, Paul developed three major principles that would solve the problem if observed with mutual love and respect.

The first was to recognize the existence of liberty in the area of non-moral matters. Attitudes must not be critical. A believer ultimately is not responsible to another believer, but rather to his heavenly master. A Christian must have absolute conviction of heart that God has granted him permission to do a certain thing. In so doing he should be able to glorify and to thank Him. He should recognize that nothing is done in a spiritual vacuum, but that everything he does affects someone else. He should know that he will give account for his exercise of Christian liberty at the judgment seat of Christ.

14:13–15:3

The second was not to offend his brother in the exercise of his liberty. Instead of being critical of the other person’s actions, the Christian should make sure that his life is above reproach. He should recognize that the source of moral defilement does not reside within the nonmoral matter itself, but in one’s attitude toward it. Thus, he should not ask: "What’s wrong with this?" Rather, he should ask: "What does my brother think about this?" He should be careful not to weaken his brother’s spiritual condition through his exercise of liberty. He should recognize that spirituality does not come from compliance to a list of Do’s and Don’ts, but rather from a yielded life producing the fruit of the Holy Spirit. If there is a conflict between his liberty and his brother’s opinion on the matter, he must be able to do it with a joyful spirit, free from any self-doubt or judgment. If he cannot do it in that way, he should not do it. The life of Christ should provide the perfect example of the proper use of rights. A believer should emulate Him by using his liberty for the edification of others, not for his own pleasure.

15:4–13

The third was to glorify God in his use of Christian liberty. Paul’s conclusion was clear: "Wherefore receive ye one another, as Christ also received us to the glory of God" (15:7). When saved Jews and believing Gentiles join in harmonious praise of God, there will be less criticism of one another.

15:14–33

Paul then expressed his desire to the Roman church to visit them on his way to Spain. This he planned to do after he took the financial contribution of the Greek churches to the needy of the Jerusalem church. It was his goal to be a pioneer missionary and to evangelize the unreached regions of the world.

16:1–27

He then commended Phebe, the person who probably was Paul’s courier, to the church. He then extended greetings to his many friends at Rome, including Aquila and Priscilla, whose home was the meeting place for the Roman Christians. He ended his greetings with a warning against false teachers, possibly the Judaizers who mixed law and grace (see Galatians). Paul then added the greetings of his co-workers to his blessing, including that of Tertius, his secretary. He ended the Epistle with a benediction exalting the gospel of salvation proclaimed by him.